As internet use grows– whether through a traditional computer, tablet, gaming device or cell phone – new techniques are being developed to conduct social research and measure people’s behavior and opinion while they are online. The Pew Research Center has been exploring these new techniques for measuring public opinion and critically evaluating how they compare to more traditional methodologies.

This report examines Google Consumer Surveys, a new tool developed by Google that interviews a stratified sample of internet users from a diverse group of about 80 publisher sites who allow Google to ask one or two questions of selected visitors as they seek to view content on the site. The sample is stratified on age, gender and location; these demographic characteristics are inferred based on the types of websites the users visit, as recorded in their DoubleClick advertising cookie and their computer’s internet address, and then is weighted by these same characteristics to parameters for all internet users from the Current Population Survey. It is neither an “opt in” survey nor a recruited panel but does not constitute a probability sample of all internet users.

The Pew Research Center remains committed to rigorous, probability-based sampling and to dual frame telephone surveys for measuring public opinion, tracking long-term trends and conducting in-depth analyses of the interrelationship of demographic characteristics and social and political values and attitudes. We continue to evaluate the performance of dual frame telephone surveys, as in our study of the impact of survey nonresponse earlier this year. It showed that “despite declining response rates, telephone surveys that include landlines and cell phones and are weighted to match the demographic composition of the population continue to provide accurate data on most political, social and economic measures.”

It is important to critically evaluate new methodologies, as our traditional methods face growing challenges, especially increasing nonresponse and rising costs. To evaluate the results obtained using Google Consumer Surveys, the Pew Research Center, in consultation with Google, embarked on a series of tests covering a wide range of topics and question types to compare results from Pew Research telephone surveys to those obtained using the Google Consumer Surveys method. This testing is ongoing. This report describes the findings of the evaluation thus far and provides a description of the Google Consumer Surveys methodology. The analysis and conclusions are solely those of the Pew Research Center.

Pew Research and Google Comparisons

From May to October, 2012, the Pew Research Center compared results for more than 40 questions asked in dual frame telephone surveys to those obtained using Google Consumer Surveys. Questions across a variety of subject areas were tested, including: demographic characteristics, technology use, political attitudes and behavior, domestic and foreign policy and civic engagement. Across these various types of questions, the median difference between 43 results obtained from Pew Research surveys and using Google Consumer Surveys was 3 percentage points. The mean difference was 6 points, which was a result of several sizeable differences that ranged from 10-21 points and served to increase the mean difference.

Differences between the Pew Research surveys and Google results occur for a number of reasons. Given that Google Consumer Surveys does not use a true probability sampling method, and its sampling frame is not of the general public, differences in the composition of the sample are potentially of greatest concern. A comparison of several demographic questions asked by Pew Research indicates that the Google Consumer Surveys sample appears to conform closely to the demographic composition of the overall internet population. Communication device ownership and internet use also aligns well for most, though not all, questions. In addition, there is little evidence so far that the Google Consumer Surveys sample is biased toward heavy internet users.

Some of the differences between results obtained from the two methodologies can be attributed to variations in how the questions were structured and administered. During the evaluation period, we typically tried to match the question wording and format. However, some exceptions had to be made since many of the questions were part of longstanding Pew Research trends and had to be modified to fit within the Google Consumer Surveys limits and the different mode of administration (online self-administered vs. interview-administered by telephone).

The context in which questions are asked could also explain some of the differences; questions in Pew Research surveys are asked as part of a larger survey in which earlier questions may influence those asked later in the survey. By contrast, only one or two questions are administered at a time to the same respondents in the Google Consumer Surveys method.

The Google Consumer Surveys method is a work in progress and the Pew Research Center’s evaluation began shortly after its inception and continued for six months. The testing is ongoing, and we will continue to evaluate their methodology.

Methodology of the Google Consumer Surveys

The Google Consumer Survey method samples internet users by selecting visitors to publisher websites that have agreed to allow Google to administer one or two questions to their users. There are currently about 80 sites in their network (and 33 more currently in testing). These include a mix of large and small publishers (such as New York Daily News, Christian Science Monitor, Reader’s Digest, Lima, Ohio News and the Texas Tribune), as well as sites such as YouTube, Pandora and others. Google is attempting to assemble a diverse publisher network covering a range of content (e.g., news, reference, arts and entertainment), size and geography. The results page for each question shows the proportion of respondents from these publisher content groups. Google excludes publishers whose sites include or link to various types of potentially offensive content. (See McDonald et al. for further information about the methodology, as well as a report on Google’s own comparison of results with external benchmarks.)

Google Consumer Surveys selects potential respondents by using inferred characteristics of visitors to the network of publisher sites to attempt to create a sample of internet users that matches national parameters for age, gender and location for the internet using population, based on estimates derived from the Census Bureau’s 2010 Current Population Survey’s Internet Use Supplement. In a stratified-sampling process, the selection of respondents, done in real-time by computer algorithms, attempts to fill each survey with the proper proportion of individuals by age, gender and location (region, state and/or zipcode) needed for all active surveys. For example, if a male in the 18-24 age group living in the Western U.S. visits a publisher in the network and is available to receive a survey, the system will randomly select among the available questions to present to that user. Users are selected by the system and cannot opt in to any survey.

Although respondents cannot volunteer to take part in the study, the resulting sample is a non-probability sample of internet users. It is unknown whether visitors to the network of publisher sites are fully representative of all internet users or what proportion of internet users are covered by the publisher network. All members of the internet using population do not have a known chance of being included in the sample. As a result, no meaningful margin of error can be calculated for projecting the results to the internet population. In addition, the non-probability sampling may result in more variation from sample to sample.

The demographic targeting used in selecting respondents is based on inferred information. Geography is inferred through a respondent’s IP address, while gender and age are inferred based on the types of websites the users visit as recorded in their DoubleClick advertising cookie. The system also deposits a short-term cookie to prevent users from being asked to participate in the same survey more than once. Errors associated with inferred demographic characteristics can influence the sampling and weighting process, even if these inferred demographics are not used in the analysis. For approximately 30-40% of the users, demographic information is not available – either because their cookies are turned off but more often because the algorithm cannot determine a trend from the websites visited as recorded in their DoubleClick advertising cookie that would suggest what gender or age they are. For results reported on the weighted sample, respondents without inferred demographic information on the variables used in weighting are excluded.

Weighting is done with multiple-cell crosstabs, where the sample size permits, that combine age, gender and location (state or region depending on the most specific geography for which a reliable estimate is available). If some variables are not available, the weighting will adjust to use any of the three characteristics that are available.

The point at which users receive the question prompt varies by publisher site. For example, questions may appear after a user attempts to access any content, views a certain number of articles or attempts to access particular types of content (such as a photo gallery). Users may complete the initial question shown to them, request an alternative question, complete some other action (such as logging into an account, signing up to receive emails, or sharing the content on social media), or decide not to view the content on that site.

Only one or two questions can be administered to the same respondent and currently there is no ability to administer questions to the same respondents over time. This may increase response rates by reducing respondent burden, but is also one of the key limitations of the Google Consumer Surveys method. Much of the political and social research conducted using survey data seeks to explore the relationship among attitudes and behaviors; such analyses require multiple questions to be asked of the same respondent. Similarly, the ability to administer only one or two questions to the same respondent means that few measures of demographic characteristics are available for analysis.

It is also difficult to ask complex questions using the Google Consumer Surveys platform. There is a limit of 125 characters on question stems and 44 characters on response options. In addition, a maximum of five response categories can be offered. These limitations mean that longer questions cannot be asked or have to be substantially modified, potentially affecting how people comprehend and answer the question.

The brevity of a Google survey does confer one important advantage, which is that surveys can be fielded very quickly: 1,000 or more responses can be obtained in a matter of a few hours, though most surveys typically run for one or two days. Consequently, Google Consumer Surveys can be used for gathering immediate reactions to events that would be difficult and expensive to measure using telephone surveys and for tracking reactions to measure how they evolve in the short and long term. These include qualitative responses to events, such as verbatim or “one word” reactions.

Demographic Characteristics

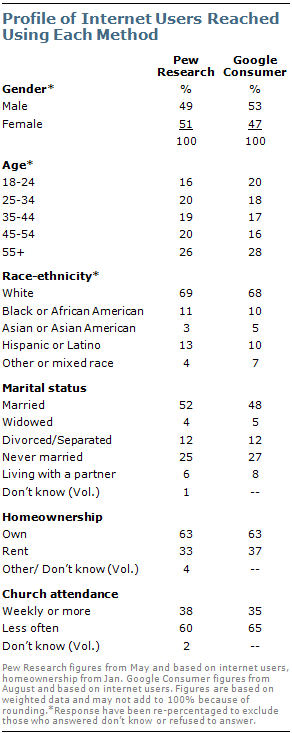

Based on tests of several demographic variables, the profile of internet users who respond to Google Consumer Surveys is similar to that of internet users in Pew Research Center surveys. The profile of Google Consumer Surveys respondents shown here is not based on Google’s inferred demographic information, but on demographic questions that were asked of respondents to Google Consumer Surveys.

Based on tests of several demographic variables, the profile of internet users who respond to Google Consumer Surveys is similar to that of internet users in Pew Research Center surveys. The profile of Google Consumer Surveys respondents shown here is not based on Google’s inferred demographic information, but on demographic questions that were asked of respondents to Google Consumer Surveys.

As discussed in more detail below, there can be substantial errors in how individual people are classified using Google’s inferred demographics (See “Assessing Google’s Inferred Demographics” below.) But in this test, Google Consumer Surveys achieved a representative sample of internet users on gender, age, race/ethnicity, marital status and home ownership when compared with internet users in Pew Research Center surveys.

The gender balance and age profile of internet users in Pew Research surveys and Google Consumer Surveys were fairly similar. In addition, both Google Consumer Surveys and Pew Research reached a similar share of white and non-white internet users.

Each source found that about half of internet users are married while about half are not, and the specific status of the unmarried (widowed, divorced, never married or living with a partner) also were very similar. And in both the Pew Research survey and the Google Consumer Surveys, 63% of internet users said they owned their home.

Weekly church attendance among internet users was comparable in the Pew Research survey and the Google Consumer Surveys. Volunteerism rates were similar in both surveys, although slightly more internet users say they volunteered in the past 12 months in the Pew Research survey than using Google Consumer Surveys (51% vs. 45%).

Weekly church attendance among internet users was comparable in the Pew Research survey and the Google Consumer Surveys. Volunteerism rates were similar in both surveys, although slightly more internet users say they volunteered in the past 12 months in the Pew Research survey than using Google Consumer Surveys (51% vs. 45%).

On two other measures of social and political engagement – talking with neighbors and contacting a public official – there were substantial differences between the results from the Pew Research and Google survey. Nearly six-in-10 (58%) in the Pew Research survey say they talk with their neighbors weekly or more, compared with 43% using Google Consumer Surveys. Nearly twice as many in the Pew Research survey as in the Google surveys said they contacted a public official in the past 12 months (34% vs. 18%). On both of these measures, however, Google results were closer to the estimates from the Current Population Survey’s Civic Engagement Supplement.

Internet and Technology Use

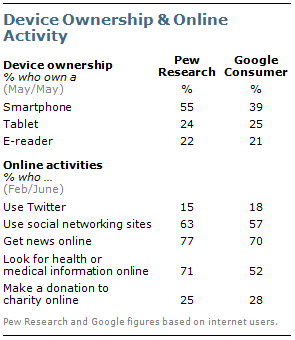

Given the Google surveys’ reliance on internet users visiting particular websites, it is especially important to determine the extent to which internet and technology use among Google’s respondents conforms to the broader population of internet users. Google’s own analysis of visitors to the Google Consumer Surveys publisher network shows that heavier internet users are more likely to appear, but the magnitude of this bias is relatively small. Comparisons of measures of device ownership and internet use in Pew Research surveys and Google Consumer Surveys confirm this.

In general, the percentage who said they owned particular devices and engaged in various online activities were fairly similar in the Pew Research surveys and the Google Consumer Surveys. The percentages of internet users saying they owned a tablet and e-readers were about the same in both the Pew Research survey and Google Consumer Surveys.

In general, the percentage who said they owned particular devices and engaged in various online activities were fairly similar in the Pew Research surveys and the Google Consumer Surveys. The percentages of internet users saying they owned a tablet and e-readers were about the same in both the Pew Research survey and Google Consumer Surveys.

In the Pew Research survey, 15% of internet users said they use Twitter, compared with 18% using Google Consumer Surveys. The number saying they donated to charity online also was comparable; 25% in the Pew Research survey and 28% using Google Consumer Surveys. Social networking use was somewhat lower in the Google Consumer Surveys (57%) than in the Pew Research survey (63%), as was getting news online (70% vs. 77%, respectively).

However, there was a difference in smartphone ownership and searching for health information online. Google’s samples reported lower levels of smartphone ownership, when asked in the same way as in the Pew Research survey, and fewer said they searched for health information online.

The Pew Research question on smartphone ownership asks “Do you currently own a smartphone, such as a Blackberry, iPhone, Android or Windows phone?” In response, 55% of internet users in a telephone survey said that they did, compared with 39% in a Google survey. However, in a separate test using different question wording, respondents were asked “What type of mobile phone do you currently own?” and were offered Android, iPhone, Blackberry, Windows phone and “other type of mobile phone” as separate choices. In this version, 53% of Google respondents reported having one of the types of smartphones.

There also was a large difference in the percentage who said they looked for health or medical information online; in a Pew Research survey 71% of internet users said they did this, compared with 52% in a Google survey.

Political Attitudes and Policy Views

Across several political measures, the results from the Pew Research Center and using Google Consumer Surveys were broadly similar, though some larger differences were observed.

Across several political measures, the results from the Pew Research Center and using Google Consumer Surveys were broadly similar, though some larger differences were observed.

On party identification, the Google sample included slightly more Republicans (27% vs. 24%) and more conservatives (40% vs. 36%) than the Pew Research survey’s sample. Similarly, ratings of Obama’s job approval were more negative using Google Consumer Surveys (at the time, 45% vs. 50% approved of Obama job performance). In a September comparison, more voters reached using Google Consumer Surveys supported Obama’s re-election than in the Pew Research survey (57% vs. 51%).

Views about the size and role of government were similar in a Pew Research survey and the Google survey. In both, more respondents said they prefer a smaller government providing fewer surveys than a bigger government providing more services.

Reported frequency of voting also was little different in the Google Consumer Surveys and the Pew Research survey. A majority of respondents to the Pew Research survey (69%) reported voting always or nearly always, compared with 65% in a Google survey.

There were larger differences between the Pew Research results and those obtained using Google Consumer Surveys on several domestic policy issues tested. But taken collectively, the direction of the differences were not consistently in a liberal or a conservative direction. On the issue of same-sex marriage, opinion was more divided in the Pew Research survey than in the Google survey. In the Pew Research survey, 48% favored and 44% opposed allowing gays and lesbians to marry legally. In the Google survey, more favored allowing same-sex marriage, by a 59% to 41% margin.

There were larger differences between the Pew Research results and those obtained using Google Consumer Surveys on several domestic policy issues tested. But taken collectively, the direction of the differences were not consistently in a liberal or a conservative direction. On the issue of same-sex marriage, opinion was more divided in the Pew Research survey than in the Google survey. In the Pew Research survey, 48% favored and 44% opposed allowing gays and lesbians to marry legally. In the Google survey, more favored allowing same-sex marriage, by a 59% to 41% margin.

The Pew Research survey found more support for Obama’s policy to allow illegal immigrants brought to the U.S. as children to remain in the country and apply for work permits (63% approve vs. 33% disapprove) than using Google Consumer Surveys (52% approve, 48% disapprove).

Opinion about the health care legislation passed by Obama and Congress in 2010 was divided in the Pew Research and Google surveys, both before and after the Supreme Court ruling upholding most of the legislation. The results of the two surveys were similar, especially after accounting for possible mode differences.

On the issue of global warming, more in the Pew Research survey said there is solid evidence that the average temperature on earth has been warming over the past few decades (67% vs. 57% using Google Consumer Surveys). But the percentage of people saying that warming is occurring mostly because of human activity was similar in the two surveys.

Across a variety of foreign policy issues, results from the Pew Research surveys and those obtained using the Google Consumer Surveys method were quite comparable. When it comes to economic and trade policy toward China, slightly more respondents in both said that it is more important to get tougher with China than to build a stronger relationship with China,

Across a variety of foreign policy issues, results from the Pew Research surveys and those obtained using the Google Consumer Surveys method were quite comparable. When it comes to economic and trade policy toward China, slightly more respondents in both said that it is more important to get tougher with China than to build a stronger relationship with China,

On the issue of withdrawing U.S. troops from Afghanistan, similar percentages in both said Obama is handling this about right. But more said that Obama was not removing troops quickly enough in the Google survey (36% vs. 28% in the Pew Research survey). A majority of the public approved of the use of drones to target terrorists in other countries in both approaches, but support was somewhat higher using Google Consumer Surveys than in the Pew Research survey (63% vs. 55%).

By about two-to-one, in both surveys, more said that good diplomacy rather than military strength is the best way to ensure peace. This was tested in two versions of a long-term trend question about political values. One version, which the Pew Research Center began tracking in 1987, asks if the respondent agrees or disagrees that “the best way to achieve peace is through military strength.” The other asks respondents to choose between two alternatives: one is the same as the original question, while the other is that “good diplomacy is the best way to achieve peace.” In Pew Research telephone surveys, fewer respondents chose military strength in the forced choice format, compared with the agree/disagree format. For both versions of the question, Google Consumer Surveys produced nearly identical results to the telephone surveys.

Reactions to the Presidential Debates

In a series of tests after each presidential debate, the Pew Research surveys and Google Consumer Surveys produced similar reactions. Both approaches found that Romney was widely viewed by registered voters who watched the debate as doing the better job. Romney had a 72% to 20% margin over Obama in the Pew Research survey on who did the better job in the first debate.

In a series of tests after each presidential debate, the Pew Research surveys and Google Consumer Surveys produced similar reactions. Both approaches found that Romney was widely viewed by registered voters who watched the debate as doing the better job. Romney had a 72% to 20% margin over Obama in the Pew Research survey on who did the better job in the first debate.

Similarly, Romney had a 57% to 16% lead over Obama according to the Google Consumer Surveys reaction, with 27% saying both candidates did about the same. In the Google reactions, Romney’s lead widened from the night of the debate to the next day.

By contrast, Obama was seen as winning the second debate and third debates, but by more modest margins. By a 48% to 37% margin, more debate watchers said in the Pew Research survey that Obama did the better job in the second debate. The Google Consumer Surveys reaction showed similar results: 50% said Obama did the better job while 32% said Romney did the better job. Views about who did the better job in the second debate changed little from the night of the debate through the following weekend.

Registered voters who watched the second debate also were asked using Google Consumer Surveys for a one-word impression of Obama and Romney in the debate. The top reactions to Obama’s performance included “liar,” “great,” “president” and “strong.” For Romney, the top reactions included “presidential,” “liar,” “awesome” and “great.”

Both the Pew Research survey and Google Consumer Survey showed Obama winning the third presidential debate, but the margin was much wider in the Pew Research survey. In the Pew Research survey, voters by a 52% to 36% margin said Obama did the better job. The Google survey found 43% of voters saying Obama did a better job vs. 37% for Romney.

The public’s reaction to the vice-presidential debate was divided in both the Pew Research survey and Google Consumer Survey. Among voters who watched the vice-presidential debate, 47% said Joe Biden did the better job while 46% said Paul Ryan did the better job, according to the Pew Research survey conducted Oct. 12-14. The Google Consumer Surveys reaction, conducted over a similar period, also found a divided reaction to the vice-presidential debate; 38% said Biden did the better job while 42% chose Ryan; 20% said they did the same.

Assessing Google’s Inferred Demographics

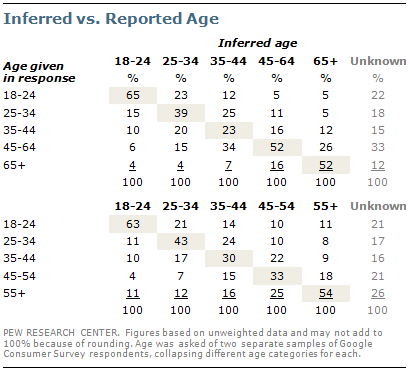

The demographic characteristics Google uses in sampling and weighting and what it provides for use in analysis are inferred based on information about the types of websites respondents have visited as recorded in their DoubleClick advertising cookie. But there is no publically available analysis of how well these inferred demographics match up to actual demographic information as reported by respondents. To assess this, Google Consumer Survey respondents were asked their gender and age so that the survey responses could be compared to the inferred data.

For 75% of respondents, the inferred gender matched their survey response. About eight-in-ten whom Google inferred were men (79%) said they were male when asked. Similarly, 72% of women based on Google’s inferred information said they were female when asked. Among those for whom Google did not infer gender, 58% said they were male and 42% female.

For 75% of respondents, the inferred gender matched their survey response. About eight-in-ten whom Google inferred were men (79%) said they were male when asked. Similarly, 72% of women based on Google’s inferred information said they were female when asked. Among those for whom Google did not infer gender, 58% said they were male and 42% female.

For age, the pattern is more mixed. Because Google limits the number of response categories for an individual question to five but provides inferred age in six categories, age was asked twice, of separate samples of respondents, collapsing different age categories for each.

For age, the pattern is more mixed. Because Google limits the number of response categories for an individual question to five but provides inferred age in six categories, age was asked twice, of separate samples of respondents, collapsing different age categories for each.

In the first comparison, from 23% to 65% report an age that was in the same category as their inferred age, that averages to about 44% among all respondents. But when adjacent age categories also are included, about 76% report an age that is the same or close to their inferred age by Google.

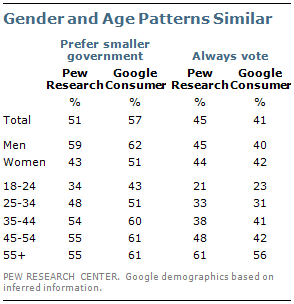

Although there are errors at the individual respondent level in Google’s inferred demographic information, especially for those in the middle age-ranges, correlations between substantive questions and gender and age are consistent with those found in Pew Research surveys.

For example, on the question of whether people prefer a smaller government or a bigger government, more men than women said they prefer a smaller government in both the Pew Research survey and the Google survey. The age pattern also was similar, with younger people being less likely in both surveys to prefer a smaller government.

For example, on the question of whether people prefer a smaller government or a bigger government, more men than women said they prefer a smaller government in both the Pew Research survey and the Google survey. The age pattern also was similar, with younger people being less likely in both surveys to prefer a smaller government.

In both surveys, men and women were about equally likely to say they always vote. And in both the Pew Research survey and the Google survey younger people were far less likely than older people to say they always vote.

The age pattern on presidential approval was quite similar in the Pew Research survey and Google Consumer Surveys; young people were more likely to approve of the job Obama is doing as president in both samples. However, fewer older people using Google Consumer Surveys approved of Obama’s job performance than in the Pew Research survey.

The age pattern on presidential approval was quite similar in the Pew Research survey and Google Consumer Surveys; young people were more likely to approve of the job Obama is doing as president in both samples. However, fewer older people using Google Consumer Surveys approved of Obama’s job performance than in the Pew Research survey.