A Look Back at How Fear and False Beliefs Bolstered U.S. Public Support for War in Iraq

Twenty years ago this month, the United States launched a major military invasion of Iraq, marking the second time it fought a war in that country in a little more than a decade. It was the start of an eight-year conflict that resulted in the deaths of more than 4,000 U.S. servicemembers and hundreds of thousands of Iraqis.

The war began March 19, 2003, with an overwhelming show of American military might, described by the unforgettable phrase “shock and awe.” Within weeks, the United States achieved the primary objective of Operation Iraqi Freedom, as the military operation was called, ousting the regime of dictator Saddam Hussein.

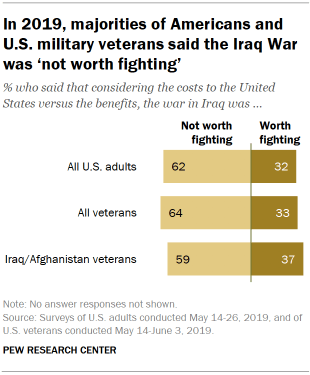

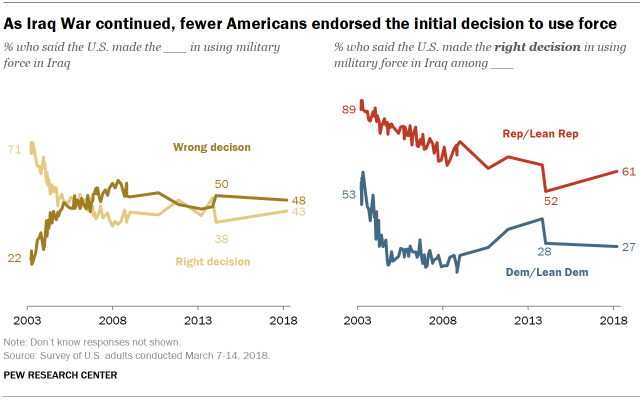

Yet the military campaign that began so auspiciously ended up deeply dividing Americans and alienating key U.S. allies. As Americans looked back on the war four years ago, 62% said it was not worth fighting. Majorities of military veterans, including those who served in Iraq or Afghanistan, came to the same conclusion.

The bleak retrospective judgments on the war obscure the breadth of public support for U.S. military action at the start of the conflict and, perhaps more importantly, in the months leading up to it. Throughout 2002 and early 2003, President George W. Bush and his administration marshaled wide backing for the use of military force in Iraq among both the public and Congress.

The administration’s success in these efforts was the result of several factors, not least of which was the climate of public opinion at the time. Still reeling from the horrors of the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks, Americans were extraordinarily accepting of the possible use of military force as part of what Bush called the “global war on terror.”

By early 2002, with U.S. troops already fighting in Afghanistan, large majorities of Americans favored the use of military force in Iraq to oust Hussein from power and to destroy terrorist groups in Somalia and Sudan. These attitudes represented “a strong endorsement of the prospective use of force compared with other military missions in the post-Cold War era,” Pew Research Center noted at the time.

Bush and senior members of his administration then spent more than a year outlining the dangers that they claimed Iraq posed to the United States and its allies. Two of the administration’s arguments proved especially powerful, given the public’s mood: first, that Hussein’s regime possessed “weapons of mass destruction” (WMD), a shorthand for nuclear, biological or chemical weapons; and second, that it supported terrorism and had close ties to terrorist groups, including al-Qaida, which had attacked the U.S. on 9/11.

As numerous investigations by independent and governmental commissions subsequently found, there was no factual basis for either of these assertions. Two decades later, debate continues about whether the administration was the victim of flawed intelligence, or whether Bush and his senior advisers deliberately misled the public about its WMD capabilities, in particular.

In the months leading up to the war, sizable majorities of Americans believed that Iraq either possessed WMD or was close to obtaining them, that Iraq was closely tied to terrorism – and even that Hussein himself had a role in the 9/11 attacks. Two decades after the war began, a review of Pew Research Center surveys on the war in Iraq shows that support for U.S. military action was built, at least in part, on a foundation of falsehoods.

The path to war: From the ‘axis of evil’ to a ‘mushroom cloud’

In his 2002 State of the Union address, Bush began making the case for why the United States might need to use military force to remove Saddam Hussein from power. “Iraq continues to flaunt its hostility toward America and to support terror,” he said. “The Iraqi regime has plotted to develop anthrax and nerve gas, and nuclear weapons, for over a decade.”

Iraq was one of three countries, along with Iran and North Korea, that constituted an “axis of evil,” according to Bush. But Iraq drew much more attention from the former president than did those countries. “This is a regime that has something to hide from the civilized world,” Bush said.

Even before his speech, Americans were inclined to believe the worst about Hussein’s regime. In a survey conducted a few weeks prior to the State of the Union, 73% favored military action in Iraq to end Hussein’s rule; just 16% were opposed. More than half (56%) said the U.S. should take action against Iraq “even if it meant U.S. forces might suffer thousands of casualties.”

Bush delivered this address, among the most memorable of his presidency, just four months after the terrorist attacks in New York City and near Washington, D.C., and Shanksville, Pennsylvania. Americans remained on edge: 62% said they were very or somewhat worried another terrorist attack was imminent.

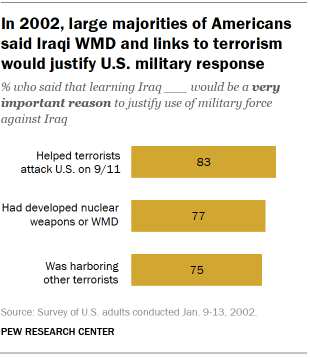

At that point, more than a year before the United States went to war, Americans overwhelmingly embraced several possible rationales for military action: 83% said that if the U.S. learned that Iraq had aided the 9/11 terrorists, that would be a “very important reason” to use military force in Iraq; nearly as many said the same if it was shown that Iraq was developing WMD (77%) or harboring other terrorists (75%).

Over the next several months, Bush and other senior officials claimed with varying degrees of certainty that there was evidence justifying the use of U.S. military force. In a speech to a Veterans of Foreign Wars convention in August 2002, former Vice President Dick Cheney was unequivocal in asserting: “Simply stated, there is no doubt that Saddam Hussein now has weapons of mass destruction. There is no doubt he is amassing them to use against our friends, against our allies, and against us.”

On other occasions, Bush and his advisers suggested that even if there was no definitive proof that Iraq possessed WMD, it was too risky not to act, given Hussein’s failure to abide by UN weapons resolutions. “The problem here is that there will always be some uncertainty about how quickly he [Hussein] can acquire nuclear weapons,” said National Security Adviser Condoleezza Rice in a CNN interview. “But we don’t want the smoking gun to be a mushroom cloud.”

Such warnings resonated strongly with Americans: Most believed that Hussein either already possessed WMD or was close to obtaining them. In October 2002, 65% of the public said Hussein was close to having nuclear weapons, while another 14% volunteered that he already possessed them. Just 11% said he was not close to developing such weapons.

That month, Congress overwhelmingly approved a resolution authorizing Bush to use the U.S. armed forces “as he determines to be necessary and appropriate” to defend the security of the United States and enforce UN resolutions on Iraq. (This month, more than 20 years after it passed, Congress is moving to repeal the resolution.)

In addition to alleging that Hussein possessed (or was on the verge of obtaining) unconventional weapons, administration officials also repeatedly linked his regime to terrorists and terrorism. For the most part, these allegations were vague and unspecified, but on occasion, senior officials – including the president himself – directly connected Iraq with al-Qaida, the terrorist group that attacked the United States on 9/11. “We know that Iraq and the al-Qaida terrorist network share a common enemy – the United States of America,” Bush said that October. “We know that Iraq and al-Qaida have had high-level contacts that go back a decade.”

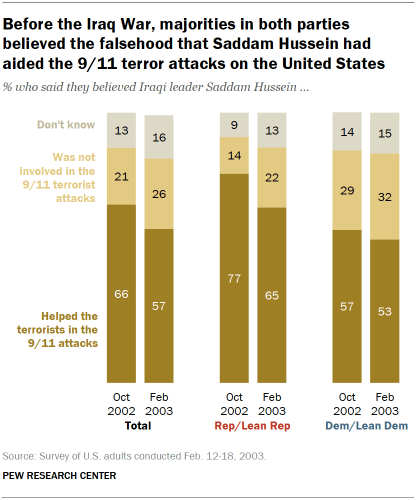

Neither Bush nor senior administration officials directly linked Iraq or its leader to the planning or execution of the 9/11 attacks. Yet a sizable majority of Americans believed that Hussein aided the terrorist attacks that took nearly 3,000 lives.

The same month that Congress approved the use of force resolution against Iraq, 66% of the public said that “Saddam Hussein helped the terrorists in the September 11th attacks”; just 21% said he was not involved in 9/11. In February 2003, a month before the war began, that belief was only somewhat less widespread; 57% thought Hussein had supported the 9/11 terrorists.

It is not entirely clear why so many Americans – including majorities in both parties – embraced this falsehood. But by connecting Hussein to terrorism and the group that attacked the United States, administration officials blurred the lines between Iraq and 9/11. “The notion was reinforced by these hints, the discussions that they had about possible links” with al-Qaida terrorists, the late Andrew Kohut, founding director of Pew Research Center, told The Washington Post after the war was underway in 2003.

As prospects for war grew, thousands took to the streets to protest

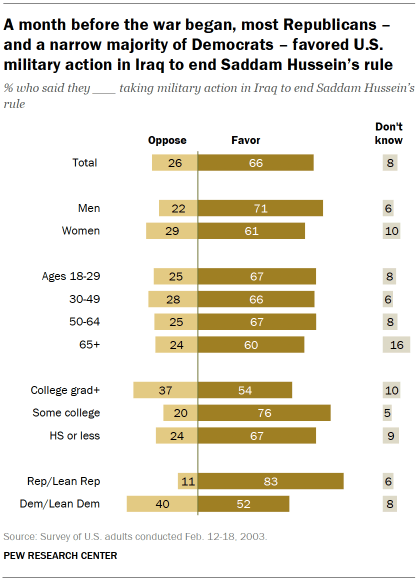

In the months leading up to the war, majorities of between 55% and 68% said they favored taking military action to end Hussein’s rule in Iraq. No more than about a third opposed military action.

However, support for military action in Iraq was consistently less pronounced among a handful of demographic and partisan groups.

The Center’s final survey before the U.S. invasion, conducted in mid-February 2003, highlighted these differences: Women were about 10 percentage points less likely than men to support the use of military force against Iraq (61% vs. 71%).

A sizable majority of Republicans and Republican-leaning independents (83%) favored the use of military force to end Hussein’s rule. Democrats and Democratic leaners were less supportive; still, more Democrats favored (52%) than opposed (40%) military action.

Yet Democrats were divided in opinions about whether to go to war in Iraq, with liberal Democrats less likely than conservative and moderate Democrats to favor using military force.

To build greater backing for the use of force among U.S. allies – and assuage lingering public concerns about war – the administration dispatched one of its most popular figures, Secretary of State Colin Powell, to the UN Security Council. In a pivotal moment in the Iraq debate, Powell presented what he described as “facts and conclusions, based on solid intelligence” to show that Iraq had failed to comply with UN weapons resolutions. “Leaving Saddam Hussein in possession of weapons of mass destruction for a few more months or years is not an option, not in a post-Sept. 11 world,” Powell said.

Powell’s address had a significant impact on U.S. public opinion, even among those who were opposed to war. Roughly six-in-ten adults (61%) said Powell had explained clearly why the United States might use military force to end Hussein’s rule; that was greater than the share saying Bush had clearly explained the stakes in Iraq (52%). Powell was particularly persuasive among those who were opposed to using force in Iraq: 39% said he had clearly explained why the U.S. may need to take military action, about twice the share saying the same about Bush.

In a last-ditch effort to prevent war, millions of protestors took to the streets in numerous cities across the world and in the U.S. on Feb. 15. While the largest demonstrations were in London and Rome, several hundred thousand antiwar protesters crowded the streets of New York City, with some carrying signs saying “No Blood for Oil.”

Americans initially rallied behind the war; then support plummeted

After the war began, administration officials were confident that the United States would quickly prevail. For a time, it appeared they would be right: U.S. and allied forces easily overwhelmed the Iraqi army.

By April 9, U.S. forces and Iraqi civilians brought down a statue of Saddam Hussein in a Baghdad square. And on May 1, Bush stood on the deck of the aircraft carrier USS Abraham Lincoln – in front of a banner proclaiming “Mission Accomplished” – and declared that major combat operations had ended.

Yet the war continued for another eight years. Public support for the use of U.S. military force in Iraq, which rose to 74% during the month that Bush gave what became known as his “Mission Accomplished” speech, never again reached that level.

As U.S. forces faced a mounting Iraqi insurgency, a growing share of Americans – especially Democrats – expressed doubts about the war. The share of Americans saying the U.S. military effort in Iraq was going well, which surpassed 90% in the war’s early weeks, fell to about 60% in late summer 2003.

There had been partisan differences in attitudes related to Iraq since Bush began raising the prospect of war in 2002. But as the war continued, these differences intensified: In October 2003, a 56% majority of Democrats said that U.S. forces should be brought home from Iraq as soon as possible, a 12-point increase from just a month earlier. By contrast, fewer than half of independents (40%) and just 20% of Republicans favored withdrawing U.S. troops.

Support for U.S. military action declined further the next year as two incidents brought the horrors of war home to Americans. In March 2004, four American private security contractors were killed and their bodies desecrated in a spate of anti-American violence. Then, the first pictures emerged of abuse of prisoners by U.S. troops at Abu Ghraib, an Iraqi prison. In a survey that May, the share of Americans who said the use of military force was going at least “fairly well” fell below 50% for the first time.

Bush’s reelection as president in November underscored the extent to which the war in Iraq had divided the nation. Among the narrow majority of voters (51%) who then approved of the decision to go to war, 85% voted for Bush; among the smaller share (45%) who disapproved, 87% voted for his Democratic opponent, John Kerry, according to national exit polls.

Public support for the war declined further during Bush’s second term. By January 2007, with the situation on the ground deteriorating, Bush defied growing calls from Democrats to withdraw U.S. forces from Iraq and instead announced that he was sending more troops to the country. What Bush called “a new way forward” in Iraq – which became more widely known as the troop surge, or surge – was a risky gambit to alter the trajectory of the war.

The new strategy, in which more than 20,000 additional U.S. forces were deployed to Iraq, was broadly unpopular with a public that had grown weary of war. By roughly two-to-one (61% to 31%), Americans opposed Bush’s plan to send additional forces to Iraq. Bush’s new strategy “triggered increased partisan polarization on the debate over what to do in Iraq,” the Center noted in its report on the January 2007 survey.

Still, while the overall impact of the surge on Iraq was intensely debated, it was widely credited with helping to reduce the level of violence in the country, both among U.S. troops and Iraqi civilians. While Americans acknowledged the improvement in the situation in Iraq, they remained deeply skeptical of the decision to go to war.

In November 2007, nearly half of Americans (48%) said the war was going very or fairly well, an 18 percentage point increase from February of that year. Yet support for withdrawing U.S. forces from Iraq was undiminished; by 54% to 41%, more Americans favored bringing troops home from Iraq as soon as possible rather than keeping troops there until the situation had stabilized. Those attitudes were virtually unchanged from earlier in 2007.

With the 2008 presidential campaign approaching – and roughly 100,000 U.S. troops still in Iraq – it seemed likely that the war would again be a major issue. During the Democratic primaries, Barack Obama repeatedly contrasted his early opposition to the war with Hillary Clinton’s 2002 Senate vote in support of the war authorization.

However, after Obama defeated Clinton for the Democratic nomination and faced John McCain in the general election, the Iraq War was increasingly overshadowed by turmoil in financial markets, which triggered a worldwide economic crisis. In national exit polls conducted after Obama’s victory over McCain, 63% of voters cited the economy as the most important issue facing the country; just 10% mentioned the war in Iraq.

During the 2008 campaign, Obama vowed to end the war in Iraq, adding that the United States “would be as careful getting out of Iraq as we were careless getting in.” Three years later, the U.S. withdrew all but a handful of its troops; in a ceremony on Dec. 15, 2011, the United States lowered the flag of command that had flown over Baghdad. President Obama’s decision drew overwhelming public support. A month before the ceremony, 75% of Americans – including nearly half of Republicans – approved of his decision to withdraw all combat troops from Iraq.

Yet Obama soon discovered how difficult it would be for the U.S. to fully disengage from Iraq. In 2014, a new security threat emerged in Iraq – the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria, or ISIS. With ISIS taking over territory in Iraq and committing high-profile terrorist acts, the group quickly became one of the U.S. public’s top security threats. In response, Obama reluctantly authorized U.S. airstrikes and dispatched a small number of U.S. forces back to Iraq. Five years later, his successor, then-President Donald Trump, claimed that the group was on the verge of defeat in Iraq and Syria, although some U.S. security officials say it remains a threat.

Judgments on the Iraq War and its impact on Bush’s legacy

The Iraq War has a long and complicated legacy. After the war officially ended, it remained an issue, to varying degrees, in both the 2012 and 2016 presidential election campaigns. Even in the 2020 campaign, nearly a decade after the war’s end, Trump and Joe Biden each portrayed themselves as better able to extricate the nation from what have been called “endless wars” – the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan.

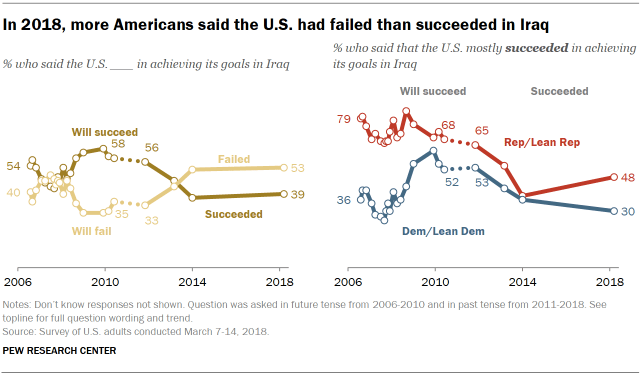

By that point, most Americans had largely moved on from the war. Shortly before the United States withdrew its forces in 2011, a majority of Americans (56%) had concluded that, despite the war’s enormous costs, the U.S. had “mostly succeeded” in achieving its goals in Iraq.

But over the next few years, that belief faded. By 2018, the 15th anniversary of the start of the war, just 39% of Americans said the U.S. had succeeded in Iraq, while 53% said it had failed to achieve its goals.

Even among Republicans, who had consistently favored the use of U.S. military force throughout the war and before it began, there were divisions over whether the U.S. had achieved its goals in Iraq. Only about half (48%) of Republicans and Republican leaners said the U.S. had succeeded, although that was 10 points higher than four years earlier.

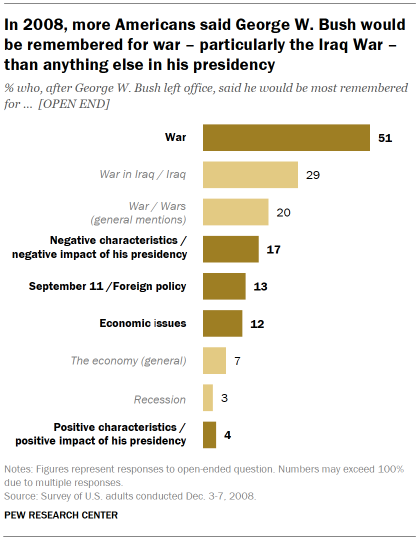

The Iraq War will long be associated with the presidency of George W. Bush, its primary architect and one of its strongest advocates. When Bush looked back at the war in his 2010 memoir, “Decision Points,” he acknowledged that mistakes had been made. Among them, he said in an interview with NBC News, was his 2003 “Mission Accomplished” speech. “No question it was a mistake,” Bush said.

As far as the failure to find WMD in Iraq, “no one was more shocked and angry than I was when we didn’t find the weapons,” Bush said. Still, he was insistent that going to war in Iraq and removing Hussein from power was the right thing to do.

The war’s impact on Americans’ views of Bush’s presidency was underscored in a December 2008 survey, conducted shortly before he left office. Asked what Bush would be most remembered for, roughly half (51%) cited wars, with 29% specifically mentioning the war in Iraq. No other issue, not even Bush’s leadership following the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks, was mentioned as frequently.

Lead image, from left: President George W. Bush declares that “major combat operations in Iraq have ended” on May 1, 2003. Soldiers in Kuwait near the Iraqi border. Baghdad burns at the start of “Operation Iraqi Freedom.” Students in Los Angeles protest the coming war. Wooden crosses for lost U.S. troops at a roadside memorial in Lafayette, California, in 2007. (Stephen Jaffe/AFP; Ian Waldie; Mirrorpix; Robert Gauthier/Los Angeles Times; Justin Sullivan, all via Getty Images)