In addition to their concerns about low and declining levels of trust in government, many Americans are anxious about the level of confidence citizens have in each other. Fully 71% think interpersonal confidence has worsened in the past 20 years. And about half (49%) think a major weight dragging down such trust is that Americans are not as reliable as they used to be.

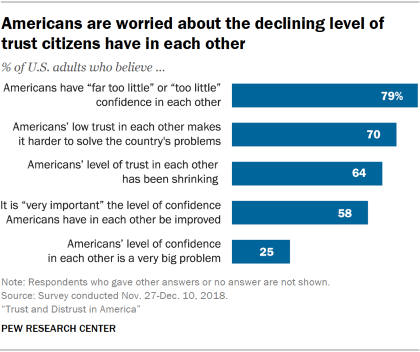

Yet there is also evidence that people worry the swing toward interpersonal distrust is an overreaction: About three-in-four Americans (79%) think their fellow citizens have too little confidence in each other. Relatedly, a fifth of adults (21%) think personal confidence in the country has worsened for little good reason. They agree with the statement that personal trust is dropping even though people are as reliable as they have always been.

Yet there is also evidence that people worry the swing toward interpersonal distrust is an overreaction: About three-in-four Americans (79%) think their fellow citizens have too little confidence in each other. Relatedly, a fifth of adults (21%) think personal confidence in the country has worsened for little good reason. They agree with the statement that personal trust is dropping even though people are as reliable as they have always been.

Whatever is causing the problem, many Americans think it needs to be remedied. Nearly six-in-ten (58%) believe it is very important to improve the level of confidence Americans have in each other, while another 35% feel it somewhat important to find ways to restore trust.

Those who feel some urgency about the problem offer a variety of reasons why they think things have deteriorated. Among the many factors on their minds, they cite social and policy woes, such as a perception that Americans are increasingly living with loneliness and isolation, as well as the nation’s continuing struggles with race relations, crime, and religion versus secularism. They also call out others’ personal traits such as laziness, greed and dishonesty. Additionally, a share of the public thinks toxic national politics and polarization have taken their toll on the way Americans think of each other.

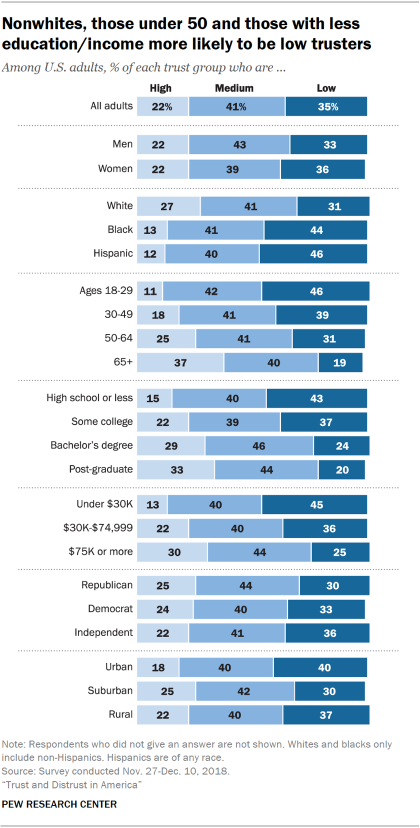

This chapter develops a personal trust scale according to survey respondents’ views about the risks and rewards of meeting and engaging with others. Americans sort into a spectrum of high, medium and low trust. Their place on the spectrum is strongly tied with their views about institutions and their dispositions toward each other, their different views about the urgency of the problems linked to distrust, their beliefs about the fallout from distrust, their personal strategies for handling trust issues and their sense of how distrust impacts dimensions of national life.

Americans think several factors have weakened interpersonal confidence, starting with the tone of national politics and the media’s coverage of it

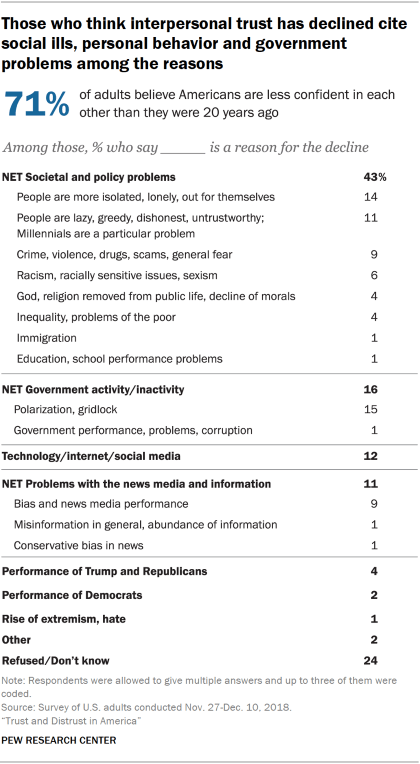

About seven-in-ten Americans (71%) think people are less confident in each other than they were 20 years ago. This compares with 22% who believe Americans are as confident in each other now as they were a generation ago and 7% who think they are more confident now than then.

Why the decline? In a closed-end question, 49% of Americans say they think citizens’ trust in each other has fallen because people are not as reliable as they used to be. This compares with 21% of Americans who think interpersonal trust has declined even though people are as reliable as they always have been. The view that others are less reliable than in the past is more common among those 50 and older, Republicans and those who lean Republican, those without a college degree, those living in households earning less than $30,000 and those living in rural areas.

The 71% who believe there has been a decline in interpersonal trust were asked in an open-ended format to name any major reasons why they think interpersonal confidence has fallen over the past generation. Many cite societal and policy problems as underlying factors. In all, 43% of those who think interpersonal trust has deteriorated mention some kind of social ill as the cause of the decline in interpersonal trust. For instance, they attribute the decline to harmful social circumstances like the isolation and loneliness of some citizens (14%), personally harmful behavior like greed and dishonesty (11%), or persistent social ills such as crime, violence, drugs and scams (9%).

Some 16% of those worried about a decline in personal trust blame polarization and government gridlock or just the poor performance of government over the past generation. About one-in-ten (11%) cite the performance of the news media, whether in biased reporting, one-sided coverage or dissemination of misinformation. Beyond that, some lay the problem at the feet of Trump and Republicans, or of Democrats.

A variety of themes recur in people’s written responses. Some, like this 49-year-old woman, lament the interplay of several modern realities: “We do not ‘need’ each other in the same ways we used to. Our lives now don’t necessarily require us to interact with anyone else beyond a surface/nominal level if we do choose it to be that way. We are, as a country, busier per capita than any other country which also does not allow for extended human interaction. The tech we use further separates us.”

A variety of themes recur in people’s written responses. Some, like this 49-year-old woman, lament the interplay of several modern realities: “We do not ‘need’ each other in the same ways we used to. Our lives now don’t necessarily require us to interact with anyone else beyond a surface/nominal level if we do choose it to be that way. We are, as a country, busier per capita than any other country which also does not allow for extended human interaction. The tech we use further separates us.”

The notion that some 21st century factors reinforce each other came up in other ways in answers like this from a 60-year-old man: “I think people don’t know their neighbors like they have in the past. Also, the polarization of opinion adds to folks’ suspicions of strangers.”

Some, like this 36-year-old woman, cited the pace of change on multiple fronts as a cause of declining personal trust: “A segment of the population is really struggling to embrace the changing demographics, the need to reconcile our nation’s painful origins, letting go of 20th century jobs founded on Industrial Revolution templates of labor, resource management and national interests.”

Many believe the fallout from political polarization is at the center of the issue of declining interpersonal trust. A 57-year-old woman summarized this view as follows: “The division caused by political opinion is making people become less trustful of others. When we see one political party unable to acknowledge the good things that the other party does, it sends a message to the people that no matter what the other party does, it’s no good. This type of attitude trickles down to the public. When the journalists only report one side of an issue, it does a disservice to the public and to the people involved in the report.”

How does this play out in everyday life? A Millennial woman described it this way: “We have become a very polarized society where people make snap judgments about others solely based on their political leanings. It wasn’t like this before. In the past people may meet someone new and get to know them and realize what they have in common, etc. Now if you meet someone and they are on the opposite end of the political scale, then people … tend to make all-encompassing assumptions about many aspects of who that person is. And doesn’t necessarily realize they have a lot in common.”

Others feel this makes even routine engagement with others more fraught. One 28-year-old man argued that this makes for self-censorship and less collaboration: “Everything is more polarized, and it is generally more difficult to disagree with someone, come to a general understanding, and move on. As you go about your day interacting with others, inherent trust is reduced because you don’t want to share your beliefs with others for fear that you will be the new target of the day. Every email, text, tweet and conversation is filtered and likely does not reflect the full belief.”

A number of respondents tied tribalism to polarization in the way this 26-year-old man did: “America has divided itself into hundreds of ‘special interest’ groups whether those are created by race, religion, sexuality, etc. and it has gotten to a point where too many people are offended by what used to be considered common language, and I think it has made too many Americans ‘afraid’ of speaking and trusting people they don’t know. Sometimes offending another person can have serious repercussions and it seems like most people are trying to play the ‘victim’ about everything.”

The dolorous impact of technology is a central concern, appearing in a number of the answers like this one: “[The] rise in social media and narrow cast media means that we converse in bubbles. This has led to polarization of discussions and beliefs. We have lost the ability to have civil public discourse and remember that good people can disagree.” A more succinct respondent put it, “Social media has become a cancerous blight on society.”

A kind of overarching theory of the problem of shrinking trust came from this 64-year-old woman: “Since the late 1980s and early 1990s, Western culture has increasingly become more tolerant of selfishness and greed and less respectful of sacrifice and honor. Also, the prevalent reliance on cell phones & computers for short, indirect and impersonal communication has lessened our assurance that others are presenting information in a sincere and honest fashion. Having a President who lies routinely does not provide the nation with a noble role model.”

Overall, Americans’ confidence in each other isn’t seen as the biggest problem facing the nation

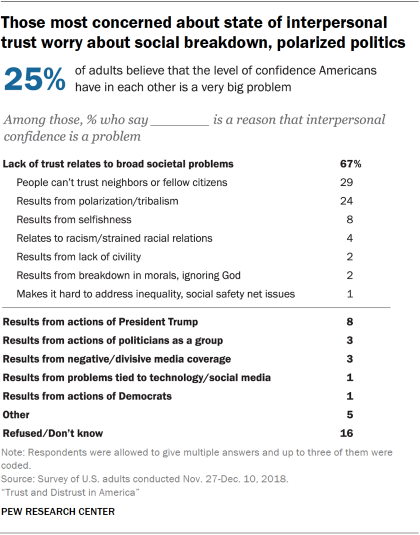

Compared with some other major concerns Americans have, their worries about interpersonal trust are relatively modest. A quarter (25%) believe that Americans’ level of confidence in each other is a very big problem and another 50% say it is a moderately big problem. That places this concern near the bottom of the list of major problems people see for the nation. In fact, more people cite as a big problem the difficulties tied to institutional distrust than issues tied to interpersonal trust. There is a bit of a partisan cast to these views: Democrats and independents who lean Democratic are more likely than Republicans and Republican leaners to think Americans’ level of confidence in each other is a big problem (29% vs. 20%).

Even though interpersonal distrust is not seen as a top-ranking issue, there is an undercurrent of urgency about addressing the problem of interpersonal trust. Fully 70% agree with another statement, “Americans’ low trust in each other makes it harder to solve many of the country’s problems.” That contrasts with 29% who back a different assertion, “The country’s problems would be just as hard to solve even if Americans’ trust in each other was higher.”

In this instance, too, Democrats are somewhat more likely than Republicans to support the idea that distrust woes are important to fix (74% vs. 66%).

Those who feel most urgently about the problem – the 25% of adults who describe lack of interpersonal confidence as a very big problem for the nation – were asked why they think that is the case. Their answers range across a host of concerns. Two-thirds of this group (67%) cite an issue tied to social or community deterioration like lack of trust among neighbors (listed by 29% of those who are highly worried about interpersonal trust as a problem), divisions among Americans tied to political polarization and “tribalism” (24%), the spread of selfishness (8%) and rising racial schisms (4%). Additionally, 8% suggest the actions of President Trump are tied to the lack of confidence Americans have in each other.

In explanations of their answers about why the level of interpersonal confidence is a very big problem, people wrote about several factors. Some started with the idea that a lack of trust stifles essential social interaction. A Gen X man put it this way: “People are allowing fear to stop them from having productive dialogue with people who have different opinions and views. The other view point is considered evil instead of just different.” A young Millennial woman linked declining interpersonal trust to the nation’s inability to solve problems, writing, “If Americans cannot learn to value and trust each other, they will never learn to value and trust those appointed to govern us. We have to be united to conquer issues.”

That view was echoed in another response: “Hate breeds distrust, distrust thrives on fear, fear turns into mistrust, and the cycle is increased when you add in poverty to intensify [people’s] basic instincts of survival.”

That view was echoed in another response: “Hate breeds distrust, distrust thrives on fear, fear turns into mistrust, and the cycle is increased when you add in poverty to intensify [people’s] basic instincts of survival.”

A significant number tie declining trust – and the ills that flow from it – to the media environment: “Our nation has lost its heart and soul; that we have faith in each other to do the right thing. These days the media only shows the worst of America and uses the good people as PR props for a political angle,” wrote a 66-year-old woman.

And Trump figures in a share of responses like this one: “The toxic atmosphere created by the current president has significantly impacted people’s confidence in each other.” Another respondent put it this way: “We appear to be experiencing an era of mistrust, apprehension, skepticism, fear, disenfranchisement, hatred of those not like ourselves, and disregard for the common good. Certain individuals have ascended to prominence by playing to the dark sides of human nature. We need leadership in whose light we can stand, and a rational and empathetic citizenry to bring about good for everyone.”

Fewer lay blame on Democrats for creating problems tied to personal trust, but there were answers along those lines. One 76-year-old man wrote, “Republicans work and pay. Democrats tax and give it away.” Another said, “[I] do not see an attempt for Democratic leaders to reach across the aisle. Too bitter that the America[n] people elected an outsider to manage what they did not.”

For those who are most anxious about the poor state of interpersonal trust, the stakes are almost cosmic. A 31-year-old man spoke for many in writing this answer: “John Marshall [the fourth chief justice of the U.S. Supreme Court] said confidence is key to our democracy. As confidence in each other deteriorates, so does the strength of our democracy.”

People sort along a continuum of personal trust, depending on their views about trusting others and the risks that might arise from that

How people think about others and how to deal with them is a useful way to understand why people worry about the effects of personal trust. There is a rich literature on these issues, often focused on the role of “social capital” in people’s lives. Our survey aims to fit into that history, though with modifications to some traditional measures of interpersonal trust.

For decades, many survey researchers have followed a three-question strategy about personal trust enshrined in the work of the General Social Survey. Our questions covered much of the same ground, but with changes in question wording. We embraced suggestions by researchers at the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, who expressed concerns about some of the traditional language and framing of the GSS questions. Our questions:

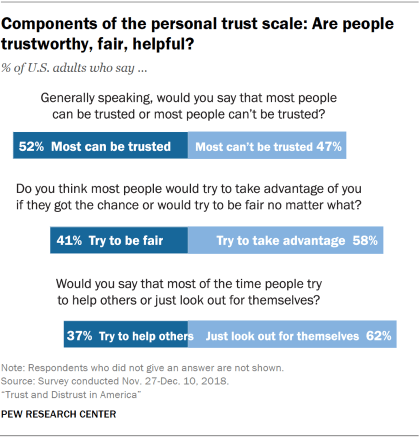

Generally speaking, would you say that most people can be trusted or most people can’t be trusted? About half (52%) opted for “most people can be trusted.” 4 (This item is modified from the GSS version.)

Generally speaking, would you say that most people can be trusted or most people can’t be trusted? About half (52%) opted for “most people can be trusted.” 4 (This item is modified from the GSS version.)- Do you think most people would try to take advantage of you if they got the chance or would try to be fair no matter what? Some 58% chose the option that people “would try to take advantage of you if they got the chance.”

- Would you say that most of the time people try to help others or just look out for themselves? About six-in-ten (62%) picked “just look out for themselves.”

We organized people’s answers into a spectrum of personal trust in the following way:

High trusters comprise 22% of the population. They are those who gave the pro-trust response to each question. They say, “people can be trusted,” that people “would try to be fair no matter what” and that people “try to help others.” Whites are twice as likely as black people or Hispanics to be high trusters. The older a person is, the more likely they are to tilt toward trusting answers. The more education someone has and the greater their household income, the greater the likelihood they sit higher on the personal trust spectrum.

High trusters comprise 22% of the population. They are those who gave the pro-trust response to each question. They say, “people can be trusted,” that people “would try to be fair no matter what” and that people “try to help others.” Whites are twice as likely as black people or Hispanics to be high trusters. The older a person is, the more likely they are to tilt toward trusting answers. The more education someone has and the greater their household income, the greater the likelihood they sit higher on the personal trust spectrum.- Low trusters make up 35% of the populace and are those who gave non-trust answers to each question. They say, “people can’t be trusted,” that others “would try to take advantage of you if they got a chance” and that people “just look out for themselves.” Nearly half of young adults (46%) fall into this group – significantly higher than older groups. Those with less income and education are also markedly more likely to be low trusters.

- Medium trusters are those who gave mixed answers, with at least one trusting answer and one non-trusting answer to the three items. That comes to 41% of the public. People in this category of social trust make up a similar share of nearly every demographic and political group examined in this survey. (Some 2% of the public falls into none of these categories because they did not answer all these questions.) The notable thing about the medium-trusters group is how relatively uniform its demographic profile is.

In the broad context of all three groups, it is striking that there are no partisan splits on these issues tied to interpersonal trust. Ideologically, those describing themselves as moderate are more likely to be low trusters and to answer each of the individual questions in this battery in a downbeat way.

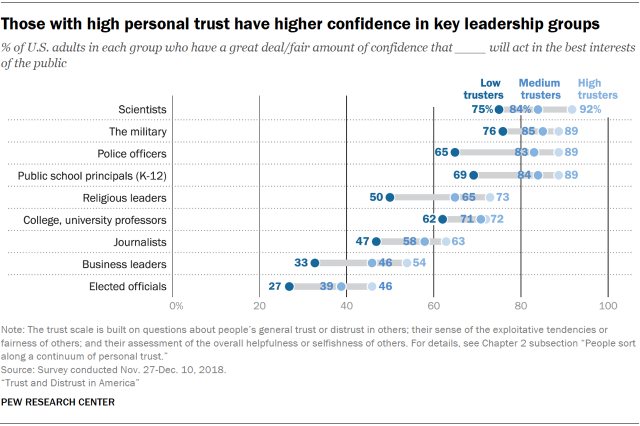

A person’s place on the personal trust spectrum often goes hand-in-hand with their views about institutional trust

People’s views on personal trust are strongly associated with their views on issues related to institutional trust. On virtually every survey question about institutions covered in Chapter 1, high trusters have significantly more confidence in institutions than low trusters, whether it is the military, police officers, business executives or religious leaders.

On other trust-related issues, low trusters stand out for their downcast views. For instance, low trusters are considerably more likely than high trusters to see various issues facing the country as “very big” problems. To begin with, low trusters are twice as likely as high trusters to think Americans’ lack of trust in each other is a very big problem (33% vs. 16%). The differences between low and high trusters also apply to such issues as the way military veterans are treated (52% of low trusters see this as a very big problem vs. 44% of high trusters who say the same), the financial stability of Social Security and Medicare (57% vs. 47%), the quality of public K-12 schools (39% vs. 30%) and the quality of roads, bridges and public transportation across the country (38% vs. 28%).

Still, Americans render at least one positive assessment in this otherwise challenging environment. While Americans have varying and nuanced views about trust in institutions and in other people, large majorities of trusters and non-trusters alike believe others trust them, personally. Some 98% of high trusters, 93% of medium trusters and 79% of low trusters agree with the statement “most people trust you.” Overall, just 11% of Americans agree with the statement “most people are suspicious of you.”

People embrace mixed strategies that combine personal caution and communal care

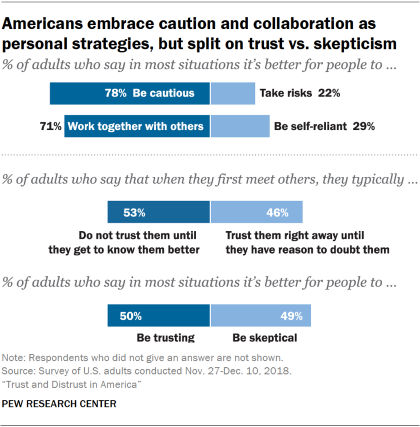

In addition to asking versions of traditional questions about interpersonal trust, this survey explored other personal strategies for dealing with others. By a wide margin, Americans think it is better to be cautious than to take risks (78% vs. 22%). However, by another lopsided verdict, they think it is better to work together with others (71%) than to be self-reliant (29%).

These divergent views suggest that the idea of working together is popular and somewhat immune to the ravages of low personal and institutional trust. For instance, fully 67% of low trusters on the personal trust scale say in most situations it is better to work together than be self-reliant.

On two other questions the public splits fairly evenly, and those divisions mirror related questions in the GSS battery. When they consider the question, “In most situations, do you think it’s better for people to be trusting or skeptical?” half say trusting, half say skeptical. When asked what typically happens when they, personally, first meet people, 53% say they do not trust them until they get to know them better, while 46% say they trust a stranger right away until they have reason to doubt that person.

On two other questions the public splits fairly evenly, and those divisions mirror related questions in the GSS battery. When they consider the question, “In most situations, do you think it’s better for people to be trusting or skeptical?” half say trusting, half say skeptical. When asked what typically happens when they, personally, first meet people, 53% say they do not trust them until they get to know them better, while 46% say they trust a stranger right away until they have reason to doubt that person.

People’s views about interpersonal trust (as measured on the personal trust scale) are closely related to their answers on these personal strategies questions. For example, low trusters are twice as likely as high trusters to say that skepticism is the best mindset for most situations (63% of low trusters say this vs. 33% of high trusters) and that a cautious approach is better than a risk-taking one (81% vs. 73%). Additionally, low trusters are more likely than high trusters to say that being self-reliant is a better choice than working together with others (33% vs. 24%).

Low trusters also are far more likely to approach others with a “prove it to me” attitude: 75% of low trusters say they do not trust others they first meet until they get to know them better. That contrasts directly with the approach high trusters take toward strangers: 73% say they trust someone they first meet right away until they have reason to doubt them.

While high trusters are more likely than others to think risk taking is a better strategy, a majority of high trusters still believe it is better to be cautious than take risks (73% vs. 27%).

When it comes to demographic differences, women are more likely than men to opt for caution than risk taking (82% vs. 74%) and to think that working with others is better than being self-reliant (76% vs. 65%). Blacks are somewhat more likely than whites to opt for skepticism (57% vs. 49%) over trust and choose working together with others (76% vs. 70%) over self-reliance. Interestingly, there are not very notable or consistent differences on these questions by age groups, by educational attainment, by community type and by household income. There are also no striking partisan or ideological differences on these questions.

Americans have more hope than despair about citizens’ behavior on some key civic and political activities – but there are notable exceptions

How does personal trust connect to people’s judgments about others’ behavior in the public arena? It turns out there are some circumstances when considerably more Americans think people will work with each other and behave decently than think they won’t. For instance, when invited to choose which statement comes closest to their view, 75% of Americans say that, “In a crisis, people will cooperate with each other even if they don’t trust each other.”

How does personal trust connect to people’s judgments about others’ behavior in the public arena? It turns out there are some circumstances when considerably more Americans think people will work with each other and behave decently than think they won’t. For instance, when invited to choose which statement comes closest to their view, 75% of Americans say that, “In a crisis, people will cooperate with each other even if they don’t trust each other.”

That compares with 24% who back the opposite point of view: “People will not cooperate with each other even in a crisis if they don’t trust each other.”

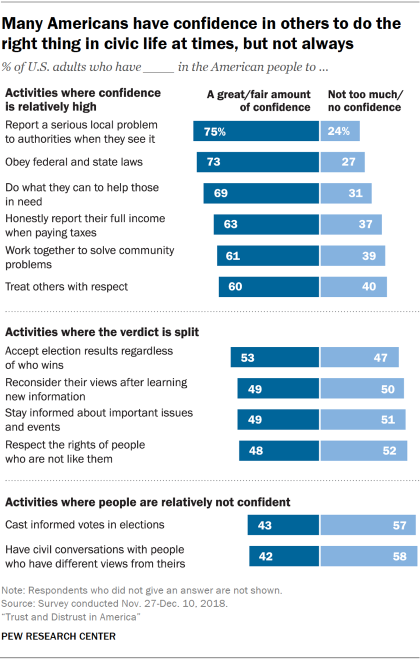

Answering a battery of questions about civic and political activities, Americans offer varying views about how their fellow citizens would behave. There are some situations in which majorities think others will act in virtuous ways. They include instances of law-abiding or civically beneficial behavior. For instance, 73% of adults have “a great deal” or “fair amount” of confidence that the American people would obey federal and state laws. Similarly, six-in-ten or more U.S. adults express confidence that others would report a serious local problem to authorities when they see it, do what they can to help those in need, honestly report their income when paying taxes, work together to solve community problems and treat others with respect.

At the same time, there are some situations in which Americans are roughly split between being confident and not confident about how others would behave. These split verdicts relate to whether others would accept election results regardless of who wins, reconsider their views after learning new information, stay informed on important issues and respect others’ rights.

Finally, there are activities where a majority of Americans are not confident in the capacities of others. Nearly six-in-ten Americans are not confident that fellow citizens are able to cast informed votes in elections or have civil conversations with those who have differing views.

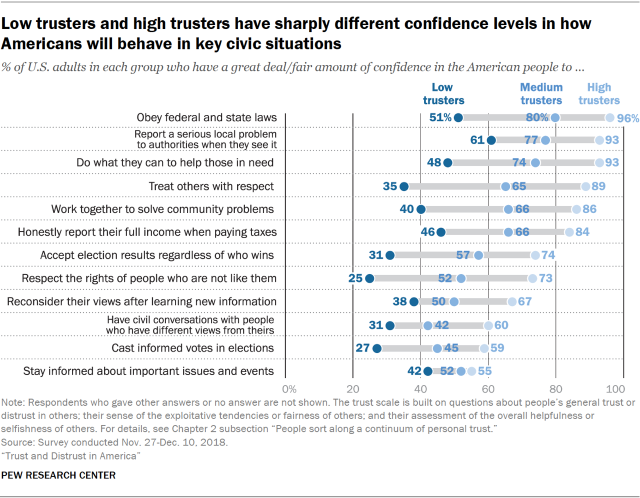

Across the board, there are sharp differences in how Americans answer these issues depending on where they sit on the personal trust scale. High trusters generally have significantly more positive views about their fellow Americans’ civic and political behaviors than do medium or low trusters. The gaps are particularly striking when it comes to how much confidence high trusters and low trusters express in Americans’ willingness to treat others with respect (54 percentage point gap between high and low trusters), respect the rights of people who are not like them (48 points), do what they can to help others in need and obey federal and state laws (both have 45-point gaps), accept election results regardless of who wins (43 points) and honestly report their full income when paying taxes (38 points).

In addition to the difference among those who have different levels of personal trust, there are other differences on these issues related to age. Those ages 65 and older have notably higher levels of confidence in their fellow citizens than young adults ages 18 to 29. It is especially evident when it comes to people’s confidence in others to respect the rights of people who are not like them, where there is a 32 percentage point gap between young adults and those 65 and older. Also, there is a 27-point gap between those age groups when it comes to confidence that others will do what they can to help those in need, a 26-point gap when the issue is confidence that people will respect each other, a 22-point spread in confidence that others will accept election results regardless of who wins, and a 21-point difference when the issue is people’s confidence that others will reconsider their views after learning new information.

It is important to note, though, that there are some areas where different age groups essentially have the same level of confidence in other Americans’ behaviors. These include their confidence in others’ willingness to honestly report their full income when paying taxes, have civil conversations with those who have differing views, stay informed on important issues and report a serious problem to local authorities.

On most of these issues there are no partisan differences of opinion – Republicans and those who lean Republican and Democrats and those who lean Democratic share similar views. However, there are a couple of issues where partisan differences arise. For instance, 76% of Republicans and Republican leaners have confidence people would do what they can to help those in need, compared with 63% of Democrats and Democratic leaners who believe that. Similarly, 56% of Republicans and leaners have confidence the American people respect the rights of people who are not like them, compared with 42% of Democrats and leaners.

Democrats, though, are more upbeat about Americans being willing to accept election results regardless of who wins. Some 57% of Democrats and leaners are confident of that, compared with 47% of Republicans and GOP leaners.

Low trusters have a more downcast sense of how distrust among Americans is affecting the country

People’s trust judgments and dispositions seem to have wide implications. Those with low interpersonal trust are more pessimistic than others across several dimensions of American life. About three-quarters of those with low trust believe that Americans’ are less confident of each other than they were 20 years ago, that Americans’ low trust in each other makes it harder to solve many of the country’s problems and that Americans have too little confidence in each other.

In addition, low trusters are more likely than high trusters to believe Americans have lost confidence in each other because people are not as reliable as they used to be and that Americans’ level of confidence in each other is a very big problem. They are also more likely than high trusters to think Americans have far too little confidence in each other (30% vs. 20%).