Our approach to generational analysis has evolved to incorporate new considerations. Learn more about how we currently report on generations, and read tips for consuming generations research.

Generational differences have long been a factor in U.S. politics. These divisions are now as wide as they have been in decades, with the potential to shape politics well into the future.

From immigration and race to foreign policy and the scope of government, two younger generations, Millennials and Gen Xers, stand apart from the two older cohorts, Baby Boomers and Silents. And on many issues, Millennials continue to have a distinct – and increasingly liberal – outlook.

These differences are reflected in generations’ political preferences. First-year job approval ratings for Donald Trump and his predecessor, Barack Obama, differ markedly across generations. By contrast, there were only slight differences in views of George W. Bush and Bill Clinton during their respective first years in office.

Just 27% of Millennials approve of Trump’s job performance, while 65% disapprove, according to Pew Research Center surveys conducted in Trump’s first year as president. Among Gen Xers, 36% approve and 57% disapprove. In Obama’s first year, 64% of Millennials and 55% of Gen Xers approved of the way the former president was handling his job as president.

Among Boomers and Silents, there is less difference in first-year views of the past two presidents; both groups express more positive views of Trump’s job performance than do Gen Xers or Millennials (46% of Silents approve, as do 44% of Boomers).

These generations were also considerably less likely than Millennials to approve of Obama’s performance early in his presidency: Among Silents, in particular, nearly as many approve of Trump’s job performance as approved of Obama (49%) during his first year in office.

These generations were also considerably less likely than Millennials to approve of Obama’s performance early in his presidency: Among Silents, in particular, nearly as many approve of Trump’s job performance as approved of Obama (49%) during his first year in office.

Increased racial and ethnic diversity of younger generational cohorts accounts for some of these generational differences in views of the two recent presidents. Millennials are more than 40% nonwhite, the highest share of any adult generation; by contrast, Silents (and older adults) are 79% white. But even taking the greater diversity of younger generations into account, younger generations – particularly Millennials – express more liberal views on many issues and have stronger Democratic leanings than do older cohorts.

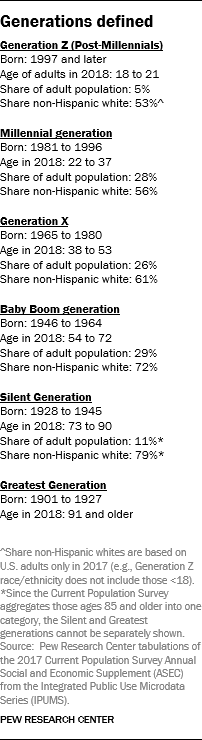

This report examines the attitudes and political values of four living adult generations in the United States, based on data compiled in 2017 and 2018. Pew Research Center defines the Millennial generation as adults born between 1981 and 1996; those born in 1997 and later are considered part of a separate (not yet named) generational cohort. Post-Millennials (Gen Zers) are not included in this analysis because only a small share are adults. For more on how Pew Research Center defines the Millennial generation and plans for future analyses of post-Millennials, see: Defining generations: Where Millennials end and Generation Z begins.

Millennials remain the most liberal and Democratic of the adult generations. They continue to be the most likely to identify with the Democratic Party or lean Democratic. In addition, far more Millennials than those in older generational cohorts favor the Democratic candidate in November’s midterm congressional elections.

In fact, in an early test of midterm voting preferences (in January), 62% of Millennial registered voters said they preferred a Democratic candidate for Congress in their district this fall, which is higher than the shares of Millennials expressing support for the Democratic candidate in any midterm dating back to 2006, based on surveys conducted in midterm years.

Generations divide on a range of political attitudes

In some cases, generational differences in political attitudes are not new. In opinions about same-sex marriage, for example, a clear pattern has been evident for more than a decade. Millennials have been (and remain) most supportive of same-sex marriage, followed by Gen Xers, Boomers and Silents.

Yet the size of generational differences has held fairly constant over this period, even as all four cohorts have grown more supportive of gays and lesbians being allowed to marry legally.

On many other issues, however, divisions among generations have grown. In the case of views of racial discrimination, the differences have widened considerably just in the past few years.

Among the public overall, 49% say that black people who can’t get ahead in this country are mostly responsible for their own condition; fewer (41%) say racial discrimination is the main reason why many black people can’t get ahead these days.

However, the percentage saying racial discrimination is the main barrier to blacks’ progress is at its highest point in more than two decades. Between 2016 and 2017, the share pointing to racial discrimination as the main reason many blacks cannot get ahead increased 14 percentage points among Millennials (from 38% to 52%), 11 points among Gen Xers (29% to 40%) and 7 points among Boomers (29% to 36%).

Silents’ views were little changed in this period: About as many Silents say racial discrimination is the main obstacle to black people’s progress today as did so in 2000 (28% now, 30% then).

Among the public overall, nonwhites are more likely than whites to say that racial discrimination is the main factor holding back African Americans. Yet more white Millennials than older whites express this view. Half of white Millennials say racial discrimination is the main reason many blacks are unable to get ahead, which is 15 percentage points or more higher than any older generation of whites (35% of Gen X whites say this).

The pattern of generational differences in political attitudes varies across issues. Overall opinions about whether immigrants do more to strengthen or burden the country have moved in a more positive direction in recent years, though – as with views of racial discrimination – they remain deeply divided along partisan lines.

Since 2015, there have been double-digit increases in the share of each generation saying immigrants strengthen the country. Yet while large majorities of Millennials (79%), Gen Xers (66%) and Boomers (56%) say immigrants do more to strengthen than burden the country, only about half of Silents (47%) say this.

There also are stark generational differences about foreign policy – and whether the United States is superior to other countries in the world.

In 2006, there were only modest generational differences on whether good diplomacy or military strength is the best way to ensure peace. Today, Millennials are by far the most likely among the four generations to express the view that good diplomacy is the best way to ensure peace (77% say this), while Silents are the least likely to say this (43%). Nearly six-in-ten Gen Xers (59%) and about half of Boomers (52%) say peace is best ensured by good diplomacy rather than military strength.

When it comes to opinions about America’s relative standing the world, Millennials and Silents also are far apart, while Boomers and Gen Xers express similar views. While fairly large shares in all generations say the U.S. is among the world’s greatest countries, Silents are the most likely to say the U.S. “stands above” all others (46% express this view), while Millennials are least likely to say this (18%).

However, while generations differ on a number of issues, they agree on some key attitudes. For example, trust in the federal government is about as low among the youngest generation (15% of Millennials say they trust the government almost always or most of the time) as it is among the oldest (18% of Silents) and the two generations in between (17% of Gen Xers, 14% of Boomers).

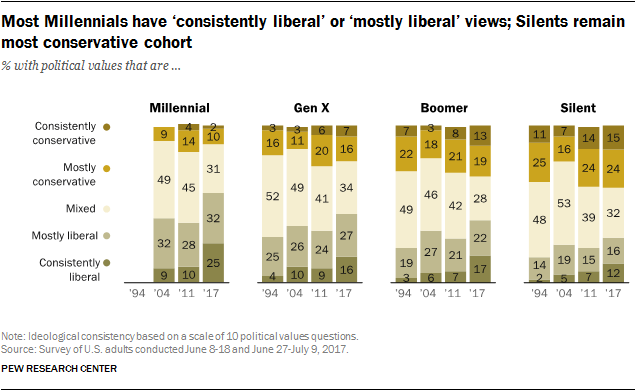

A portrait of generations’ ideological differences

Since 1994, Pew Research Center has regularly tracked 10 measures covering opinions about the role of government, the environment, societal acceptance of homosexuality, as well as the items on race, immigration and diplomacy described above.

As noted in October, there has been an increase in the share of Americans expressing consistently liberal or mostly liberal views, while the share holding a mix of liberal and conservative views has declined.

In part, this reflects a broad rise in the shares of Americans who say homosexuality should be accepted rather than discouraged, and that immigrants are more a strength than a burden for the country.

Across all four generational cohorts, more express either consistently liberal or mostly liberal opinions across the 10 items than did so six years ago.

Yet Millennials are the only generation in which a majority (57%) holds consistently liberal (25%) or mostly liberal (32%) positions across these measures. Just 12% have consistently or mostly conservative attitudes, the lowest of any generation. Another 31% of Millennials have a mix of conservative and liberal views.

Among Gen Xers and Boomers, larger shares also express consistently or mostly liberal views than have conservative positions. Silents are the only generation in which those with consistently or mostly conservative views (40%) outnumber those with liberal attitudes (28%).

Racial and ethnic diversity and religiosity across generations

Millennials are the most racially and ethnically diverse adult generation in the nation’s history. Yet the next generation stands to be even more diverse.

More than four-in-ten Millennials (currently ages 22 to 37) are Hispanic (21%), African American (13%), Asian (7%) or another race (3%). Among Gen Xers, 39% are nonwhites.

The share of nonwhites falls off considerably among Boomers (28%) and Silents (21%). Among the two oldest generations, more than 70% are white non-Hispanic.

Generational differences are also evident in another key set of demographics – religious identification and religious belief. In Pew Research Center’s 2014 Religious Landscape Study of more than 35,000 adults, nearly nine-in-ten Silents identified with a religion (mainly Christianity), while just one-in-ten were religiously unaffiliated. And among Boomers, more than eight-in-ten identified with a religion, while fewer than one-in-five were religious “nones.” Among Millennials, by contrast, upwards of one-in-three said they were religiously unaffiliated.

And already wide generational divisions in attitudes about whether it is necessary to believe in God in order to be moral and have good values have grown wider in recent years: 62% of Silents say belief in God is necessary for morality, but this view is less commonly held among younger generations – particularly Millennials. Just 29% of Millennials say belief in God is a necessary condition for morality, down from 42% in 2011.