A major factor in the public’s negative attitudes about the federal government is its deep skepticism of elected officials. Unlike opinions about government performance and power, Republicans and Democrats generally concur in their criticisms of elected officials.

Asked to name the biggest problem with government today, many cite Congress, politics, or a sense of corruption or undue outside influence. At the same time, large majorities of the public view elected officials as out of touch, self-interested, dishonest and selfish. And a 55% majority now say that ordinary Americans would do a better job at solving the nation’s problems than their elected representatives.

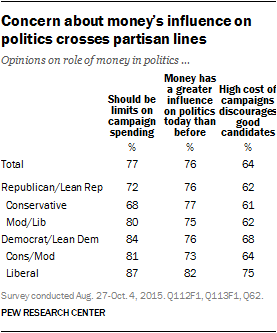

The 2016 campaign is on pace to break records for campaign spending. A large majority of Americans (76%) – including identical shares of Republicans and Democrats – say money has a greater role on politics than in the past. Moreover, large majorities of both Democrats (84%) and Republicans (72%) favor limiting the amount of money individuals and organizations can spend on campaigns and issues.

Few say elected officials put the country’s interests before their own

Just 19% say elected officials in Washington try hard to stay in touch with voters back home; 77% say elected officials lose touch with the people quickly.

A similar 74% say most elected officials “don’t care what people like me think”; just 23% say elected officials care what they think.

The public also casts doubt on the commitment of elected officials to put the country’s interests ahead of their own. Roughly three-quarters (74%) say elected officials put their own interests ahead of the country’s, while just 22% say elected officials put the interests of the country first.

These views are widely held across the political spectrum, though conservative Republicans and Republican leaners are particularly likely to say elected officials are self-interested: 82% say this, compared with 71% of moderate and liberal Republicans, and similar proportions of conservative and moderate (69%) and liberal (73%) Democrats.

Negative views of politicians on these measures are nothing new, though the sense that politicians don’t care what people think is more widely held in recent years: Today, 74% say this, up from 69% in 2011, 62% in 2003, and a narrower 55% majority in 2000.

Majorities across party lines say politicians don’t care much about what they think, though as has been the case since 2011, more Republicans than Democrats currently say this (78% vs. 69%). In 2004, when both the presidency and Congress were held by the GOP, Democrats (71%) were more likely than Republicans (54%) to say elected officials in Washington didn’t care much about them. Throughout much of the late 1990s, there were no significant partisan differences in these views.

Top problems of elected officials

When asked to name in their own words the biggest problem they see with elected officials in Washington, many Americans volunteer issues with their integrity and honesty, or mention concerns about how they represent their constituents.

When asked to name in their own words the biggest problem they see with elected officials in Washington, many Americans volunteer issues with their integrity and honesty, or mention concerns about how they represent their constituents.

The influence of special interest money on elected officials tops the list of named problems; 16% say this. Another 11% see elected officials as dishonest or as liars. These concerns are named by similar proportions of Republicans and Democrats.

One-in-ten respondents (10%) say elected officials are out of touch with Americans, and another 10% say they only care about their political careers. Republicans and Republican-leaning independents are slightly more likely than Democrats to name these as problems.

In contrast, Democrats are twice as likely as Republicans to volunteer that the biggest problem with elected officials is that they are not willing to compromise (14% vs. 7%).

Elected officials seen as ‘intelligent,’ not ‘honest’

To the general public, elected officials in Washington are not much different from the typical American when it comes to their intelligence or their work ethic, but they are viewed as considerably less honest, somewhat less patriotic and somewhat more selfish.

Two-thirds (67%) say that “intelligent” describes elected officials at least fairly well, the same share that says this about the typical American. Business leaders, by comparison, are seen as more intelligent (83% say this describes them at least fairly well).

About half of Americans say elected officials (48%) and average Americans (50%) are lazy; just 29% say this about business leaders.

But assessments of elected officials’ honesty are far more negative. Just 29% say that “honest” describes elected officials at least fairly well, while 69% say “honest” does not describe elected officials well. Business leaders are viewed more positively: 45% say they are honest. And nearly seven-in-ten (69%) consider the typical American honest.

About six-in-ten (63%) view elected officials as patriotic, a larger share than says this about business leaders (55%). Still, far more (79%) view ordinary Americans as patriotic than say this about elected officials.

And the public overwhelmingly thinks of elected officials as selfish: 72% say this describes them at least fairly well, including 41% who say this trait describes them “very well.” Though similar shares say the term “selfish” applies at least fairly well to both business leaders (67%) and the typical American (68%), fewer say it describes those groups very well.

Majorities of Republicans and Republican-leaning independents, and Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents, see elected officials as intelligent, patriotic and selfish, though there are modest differences in the ratings of elected officials across party lines.

Only about a third of Democrats (34%) and even fewer Republicans (25%) say “honest” describes elected officials. Similarly modest gaps are seen on other traits, with Democrats consistently viewing elected officials more positively (and less negatively) than Republicans.

There are few differences between Democrats and Republicans on views of the typical American. Majorities in both parties rate the typical American as intelligent, honest and patriotic, albeit selfish.

Republicans express more positive views of business leaders than do Democrats. More Republicans than Democrats say “patriotic” describes business leaders very or fairly well (66% vs. 48%). And while Democrats rate elected officials and business leaders similarly on honesty (respectively, 34% and 39% say each is honest), Republicans are twice as likely to call business leaders honest than to say this about elected officials (55% vs. 25%).

Views of elected officials and views of government

Just 12% of Americans have attitudes across a variety of measures that suggest they view elected officials positively (tending to rate elected officials as honest, intelligent, in touch with and concerned about average Americans, and putting the country’s interest above their own self-interest), while 57% largely view elected officials negatively (tending to take the opposing view on these measures); about three-in-ten (31%) hold about an equal mix of positive and negative views of politicians.

Just 12% of Americans have attitudes across a variety of measures that suggest they view elected officials positively (tending to rate elected officials as honest, intelligent, in touch with and concerned about average Americans, and putting the country’s interest above their own self-interest), while 57% largely view elected officials negatively (tending to take the opposing view on these measures); about three-in-ten (31%) hold about an equal mix of positive and negative views of politicians.

These views of elected officials are strongly correlated with overall attitudes about government. Among those with positive views of politicians, 53% say they trust government all or most of the time; among those with negative views, just 7% do. And while 42% of those with positive views say they are “basically content” with the federal government and just 4% express anger, just 9% of those with negative views of elected officials say they are content and fully 29% express anger.

Compromising with the other party

The public is also divided over the extent to which elected officials should make compromises with people with whom they disagree. While 49% of the public say they like elected officials who compromise, 47% say they prefer those who stick to their positions.

Among partisans and leaning independents, though, there is a clearer preference. Nearly six-in-ten Republicans and Republican leaners (59%) like elected officials who stick to their positions. The preference is especially strong among conservative Republicans, 65% of whom say this.

In contrast, 60% of Democrats and Democratic leaners prefer elected officials who make compromises over those who stick to their positions. Two-thirds of liberal Democrats (67%) agree. This ideological divide over compromise in principle is little different today from in recent years.

More people blame lawmakers than the political system

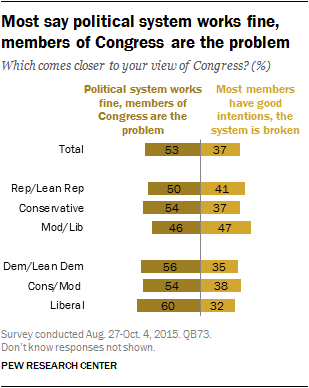

As was the case five years ago, more Americans blame problems with Congress on the members themselves, not a broken political system. Overall, 53% say the political system works just fine, and that elected officials are the root of the problems in Congress; 37% say most members of Congress have good intentions, and it’s the political system that is broken (37%).

As was the case five years ago, more Americans blame problems with Congress on the members themselves, not a broken political system. Overall, 53% say the political system works just fine, and that elected officials are the root of the problems in Congress; 37% say most members of Congress have good intentions, and it’s the political system that is broken (37%).

There are only modest partisan or demographic differences on this question, though moderate and liberal Republicans and leaners are somewhat more likely than other partisan and ideological groups to say problems are systemic (47% say this, compared with no more than 38% of those in other ideological groups).

Views of the role of money in politics

The vast sums of money flowing into the 2016 presidential election have once again brought attention to the issue of campaign finance.

This issue resonates broadly with the public: 77% of Americans say there should be limits on the amount of money individuals and organizations can spend on political campaigns and issues. Just 20% say that individuals and organizations should be able to spend freely on campaigns.

The perception that the influence of money on politics is greater today than in the past is also widely shared. Roughly three-quarters of the public (76%) believe this is the case, while about a quarter (22%) says that money’s influence on politics and elected officials is little different today than in the past.

And as the presidential campaign continues, nearly two-thirds of Americans (64%) say that the high cost of running a presidential campaign discourages many good candidates from running. Only about three-in-ten (31%) are confident that good candidates can raise whatever money they need.

Broad concerns about money in politics – and the specific worry that costly campaigns discourage worthy candidates – are not new. In a January 1988 face-to-face survey, 64% said the high cost of campaigns acts as a barrier to many good candidates.

Most Americans, including majorities in both parties, believe that new laws would be effective in reducing the role of money in politics. Roughly six-in-ten overall (62%) say that new laws would be effective in limiting the role of money in politics; 35% say new laws would not be effective in achieving this goal.

Bipartisan support for limiting campaign spending

Opinions on campaign finance and its effects on the political system are widely shared; majorities across demographic and partisan groups say there should be limits on campaign spending, that money’s impact on politics has increased and that the high cost of campaigns is driving away good candidates.

Partisan differences on all three measures are modest. Republicans and Republican-leaning independents (72%) are less likely than Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents (84%) to say that there should be limits on campaign spending. However, support for spending limits is high even among conservative Republicans and leaners –roughly two-thirds (68%) think there should be limits on how much individuals and organizations can spend.

Democrats and leaners are somewhat more likely to say that the high cost of campaigns today discourages good candidates: 68% say this compared with 62% of Republicans and leaners.

While most Americans believe that new laws would be effective in reducing the role of money in politics, there are educational and partisan differences in how widely these views are held.

Fully three-quarters of those with post-graduate degrees say new laws would be effective in this regard, compared with 57% of those with no more than a high school education.

More Democrats and leaners (71%) than Republicans and leaners (58%) say that new laws would be effective in limiting the influence of money in politics. Nonetheless, majorities across all educational and partisan categories say that new laws could be written that would effectively reduce the role of money in politics.

Interactive

Interactive