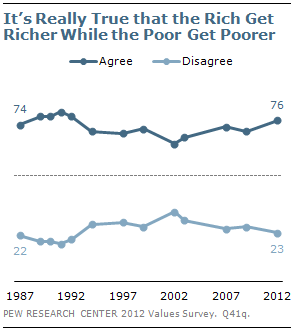

The public has long believed there is a growing financial divide between the rich and poor in this country. On a basic measure of inequality, a substantial majority continues to agree that “today it’s really true that the rich just get richer while the poor get poorer.”

Moreover, more Americans see a greater divergence in the standards of living between the middle class and poor than did so in the mid-1980s. And even as the personal financial assessments of more affluent Americans have rebounded since 2009, those of people in the lowest income tier have not. Currently, people in the lowest-income group express less financial satisfaction than at any time in the last 25 years.

Moreover, more Americans see a greater divergence in the standards of living between the middle class and poor than did so in the mid-1980s. And even as the personal financial assessments of more affluent Americans have rebounded since 2009, those of people in the lowest income tier have not. Currently, people in the lowest-income group express less financial satisfaction than at any time in the last 25 years.

Despite these widespread perceptions of economic inequality, there are no indications that class resentment is on the rise in the United States. Wealthy people who achieve success through hard work are as widely admired today as they were in the first Pew Research Center political values survey in 1987. On the other hand, most Americans do not admire those who simply are rich, with no mention of them becoming wealthy through their own efforts.

When it comes to opinions about the poor, more say that people are poor because of circumstances beyond their control than because of a lack of effort on their part. And a sizable majority continues to say that poor people work but are unable to earn enough money; far fewer say that they do not work.

Moreover, while more Americans say that living standards among the poor and middle class are growing apart than did so in the 1980s, a plurality continues to say that the values of the poor and middle class have become more similar, rather than more different, in recent years.

For the most part, there are larger partisan gaps than educational or income differences in opinions about wealth, poverty and inequality. But there are some notable exceptions, including in opinions about personal success and the value of hard work. People with less education and lower incomes are consistently more likely than those with better education and higher incomes to say that success is outside of an individual’s control. Even on these measures, however, socioeconomic differences in views are no wider today than they were in the first political values survey in 1987.

Perceptions of Economic Inequality

In 1986, the public was evenly divided over whether the gap in living standards between the middle class and poor was growing; 40% said it was getting wider, while 39% said it was narrowing. But today, more than twice as many say the gap in living standards has widened than narrowed over the past decade (61% vs. 28%). The belief that there is a larger economic gap between the middle class and poor has increased among most demographic and political groups since 1986.

In 1986, the public was evenly divided over whether the gap in living standards between the middle class and poor was growing; 40% said it was getting wider, while 39% said it was narrowing. But today, more than twice as many say the gap in living standards has widened than narrowed over the past decade (61% vs. 28%). The belief that there is a larger economic gap between the middle class and poor has increased among most demographic and political groups since 1986.

An even higher percentage (76%) sees a wider gap in living standards between the middle class and rich compared with 10 years ago. Just 16% say the gap in living standards has narrowed over this period.

An even higher percentage (76%) sees a wider gap in living standards between the middle class and rich compared with 10 years ago. Just 16% say the gap in living standards has narrowed over this period.

Majorities across all major demographic groups say that gaps in the standard of living between the poor and the middle class – and the middle class and the rich – have gotten wider over the past 10 years.

While there are partisan differences in these views, they are fairly modest. Majorities of Democrats (66%) and independents (62%) say the gap in living standards between the middle class and poor is wider than it was 10 years ago; about half of Republicans (51%) agree. Large majorities of all three groups say the gap in living standards between the rich and the middle class is wider than it was a decade ago.

Perceptions of Values Gaps

The public sees a wider economic gap between the poor and middle class than it did in 1986. But its views of the values differences between the two groups are largely unchanged.

The public sees a wider economic gap between the poor and middle class than it did in 1986. But its views of the values differences between the two groups are largely unchanged.

As in 1986, a greater percentage says the values of the poor and middle class have gotten more similar – rather than more different – over the past 10 years. Nearly half (47%) say the values of the poor and middle class have become more similar, while 41% say they have become more different.

In the 1986 survey by Gallup and the Joint Center for Political and Economic Studies, 44% said values of the middle class and poor had become more similar while 33% said they had grown more different.

In the current survey, far more say the values of the rich and the middle class have diverged over the past decade than say that about the poor and middle class. Nearly seven-in-ten (69%) say the values of the rich and middle class have become more different over the past ten years; only 41% say the same about the values held by the poor and middle class.

In the current survey, far more say the values of the rich and the middle class have diverged over the past decade than say that about the poor and middle class. Nearly seven-in-ten (69%) say the values of the rich and middle class have become more different over the past ten years; only 41% say the same about the values held by the poor and middle class.

A relatively small percentage (23%) thinks that rich people have lower moral values than other Americans. A majority (55%) says that rich people have about the same moral values as others and 15% say rich people’s values are higher.

Fully two-thirds of Americans (67%) say that the poor have about the same moral values as other Americans; 14% say the poor have lower values while about the same percentage (12%) says they have higher values.

The Rich-Poor Divide

The belief that the “rich just get richer while the poor get poorer” has remained stable across income groups since 1987. Those in the lowest quartile of family income –$20,000 a year or less in the current survey – continue to be somewhat more likely to agree with this sentiment than those in highest income quartile ($75,000 or more) (85% vs. 70%).

But the partisan gap in these attitudes is large and growing. The percentage of Democrats agreeing that the “rich get richer” (92%) is as high as it has ever been and has increased by eight points since the previous political values survey in 2009. Nearly three-quarters of independents (73%) agree that the rich g et richer, while a much smaller majority of Republicans (56%) do so.

et richer, while a much smaller majority of Republicans (56%) do so.

Partisan differences on this measure have never been wider. In the first political values survey in 1987, 84% of Democrats said the rich got richer and the poor got poorer, compared with 74% of independents and 62% of Republicans.

Success Admired When Achieved through Work

Nearly nine-in-ten (88%) say that they “admire people who get rich by working hard”; about half (49%) completely agree. These opinions are little changed from previous political values surveys. Yet the key to this admiration is the effort: just 27% agree with statement “I admire people who are rich” while 67% disagree.

Nearly nine-in-ten (88%) say that they “admire people who get rich by working hard”; about half (49%) completely agree. These opinions are little changed from previous political values surveys. Yet the key to this admiration is the effort: just 27% agree with statement “I admire people who are rich” while 67% disagree.

As in the past, there are small demographic, educational and income differences in how people view those who have worked hard to get wealthy. Yet for the first time, sizable political differences have emerged.

To be sure, overwhelming percentages of Republicans (95%), Democrats (86%) and independents (88%) admire those who have gotten rich through hard work. But Republicans are now far more likely to completely agree: 64% of Republicans say this, compared with 48% of independents and 42% of Democrats. Since 2009, there has been a 12-point increase in the share of Republicans who completely agree that they admire people who have gotten rich by working hard. Opinions among Democrats and independents have shown little change.

To be sure, overwhelming percentages of Republicans (95%), Democrats (86%) and independents (88%) admire those who have gotten rich through hard work. But Republicans are now far more likely to completely agree: 64% of Republicans say this, compared with 48% of independents and 42% of Democrats. Since 2009, there has been a 12-point increase in the share of Republicans who completely agree that they admire people who have gotten rich by working hard. Opinions among Democrats and independents have shown little change.

There also are partisan differences over the statement: “I admire people who are rich.” There is no political or demographic group in which a majority agrees, but Republicans (40%) are more likely than Democrats (26%) or independents (21%) to express admiration for the rich.

There also are partisan differences over the statement: “I admire people who are rich.” There is no political or demographic group in which a majority agrees, but Republicans (40%) are more likely than Democrats (26%) or independents (21%) to express admiration for the rich.

People with higher family incomes are more likely than those with lower incomes to admire people who are rich. Nearly four-in-ten (37%) of those with incomes of $75,000 or more say they admire people who are rich. That compares with 27% of those with incomes of $30,000-$75,000 and 22% of those who earn less than $30,000.

Why Are People Poor?

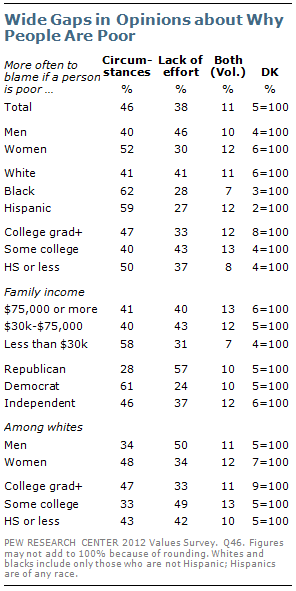

Overall, 46% say that circumstances beyond one’s control are more often to blame if a person is poor, while 38% say that an individual’s lack of effort is more often to blame; 11% blame both. These views have fluctuated over the years, but opinion typically has been divided or pluralities have blamed circumstances, rather than a lack of effort, for people being poor.

In the current survey, more women (52%) than men (40%) blame circumstances beyond one’s control for why a person is poor. Majorities of blacks (62%) and Hispanics (59%) also blame external circumstances, while whites are evenly divided: 41% say circumstances beyond a person’s control are mostly to blame while an identical percentage says it is mostly a person’s lack of effort.

In the current survey, more women (52%) than men (40%) blame circumstances beyond one’s control for why a person is poor. Majorities of blacks (62%) and Hispanics (59%) also blame external circumstances, while whites are evenly divided: 41% say circumstances beyond a person’s control are mostly to blame while an identical percentage says it is mostly a person’s lack of effort.

Notably, whites are divided in opinions about why someone is poor. White college graduates mostly blame circumstances beyond a person’s control (47% to 33%), while whites with some college experience say it mostly is because of a lack of effort (49% to 33%). Whites with a high school education or less are evenly divided (43% circumstances, 42% lack of effort).

By more than two-to-one (61% to 24%), Democrats say circumstances beyond a person’s control are primarily to blame for them being poor. By about the same margin (57% to 28%), Republicans blame a person’s lack of effort. Among independents more say circumstances, rather than a lack of effort, are mostly to blame (46% vs. 37%).

Most Say the Poor Work, but Can’t Earn Enough

Nearly two-thirds of Americans (65%) say that most poor people in the U.S. work but are unable to earn enough money; just 23% say the poor do not work. These opinions have changed little over the past decade, but opinion was more evenly divided in December 1994,  shortly after Republicans won control of Congress (49% work, 44% do not).

shortly after Republicans won control of Congress (49% work, 44% do not).

Majorities of men, women, whites, blacks and Hispanics say that poor people work but cannot earn enough money. And there are only modest differences in these opinions by income or educational attainment.

Yet there are sharp ideological differences. Fully 89% of liberal Democrats and 78% of moderate and conservative Democrats say poor people work but cannot earn enough; 64% of independents agree. But only about half of moderate and liberal Republicans (53%) say that poor people work but do not earn enough. Conservative Republicans are evenly divided: 43% say the poor in this country work but cannot earn enough, while 40% say most poor people do not work.

Economic Gaps over Personal Empowerment

Despite the struggling economy, majorities continue to reject the idea that hard work offers little guarantee of success and that success is outside of an individual’s control. As in the past, those with lower incomes and less education remain far more likely than those with higher incomes and more education to agree with these statements.

Despite the struggling economy, majorities continue to reject the idea that hard work offers little guarantee of success and that success is outside of an individual’s control. As in the past, those with lower incomes and less education remain far more likely than those with higher incomes and more education to agree with these statements.

Currently, just 35% agree that “hard work offers little guarantee of success”; 63% disagree. Despite tough economic times and high unemployment, these opinions have not changed substantially in recent years. This stands in contrast with public reactions to the economic downturn in the early 1990s. In 1992, 45% said they felt hard work was no guarantee of success.

In the current survey, 46% of those with family incomes of $20,000 or less say that hard work offers little guarantee of success, compared with just 20% of those with incomes of $75,000 a year or more. And while 45% of those with no more than a high school education are skeptical that hard work leads success, just 25% of college graduates say this.

The pattern is similar in attitudes about whether individuals are largely in control of their own fates. Overall views are identical to opinions about whether hard work leads to success: Currently, 35% agree that “success in life is pretty much determined by forces outside our control,” while 63% disagree. These opinions also have changed little over the past 25 years; in the first values survey in 1987, 57% rejected the idea that success is largely determined by outside forces while 38% agreed.

As was the case in the first political values survey, about twice as many of those in the lowest quartile of family income than those in the highest quartile say that success is determined largely by outside forces (50% vs. 22%).

As was the case in the first political values survey, about twice as many of those in the lowest quartile of family income than those in the highest quartile say that success is determined largely by outside forces (50% vs. 22%).

There also are partisan and race differences in views about whether success is determined by outside forces and whether hard work offers little guarantee of success. But these gaps are somewhat more modest than differences by education and income.

The opinion divides are as substantial among whites as they are in the general public. In the current survey, 47% of low-income whites say that success is mostly determined by outside forces, compared with just 21% of high-income whites.

Financial Satisfaction Equals All-Time Low

Currently, 53% agree that “I’m pretty well satisfied with the way things are going for me financially.” That equals the lowest percentage agreeing with this statement in the last 25 years, from April 2009. In 2007, before the recession, 61% said they were pretty well satisfied with their finances.

While the percentage of the public expressing satisfaction with their finances is unchanged from three years ago, lower-income Americans have become less satisfied with their finances while financial satisfaction among upper-income people has recovered after falling sharply during the teeth of recession in 2009.

Just 30% of those in the lowest family income category – less than $20,000 a year – say they are “pretty well satisfied” financially. That is the lowest percentage of this group that has expressed financial satisfaction in the 25 years of Pew Research political values surveys.

Just 41% of those in the next lowest income group ($20,000 to $40,000) say they are satisfied financially; that is a decline of 10 points since 2009 and also an all-time low.

Just 41% of those in the next lowest income group ($20,000 to $40,000) say they are satisfied financially; that is a decline of 10 points since 2009 and also an all-time low.

In contrast, upper-income people (those with incomes of $75,000 or more), whose assessments of their personal finances fell sharply between 2007 and 2009, offer more positive views than they did three years ago. Currently, 74% say they are pretty well satisfied financially; that is up nine points from 2009 though still below 2007 levels (85%).

Americans’ perceptions of financial stress also have increased in recent years. Nearly half (48%) agree that “I often don’t have enough money to make ends meet” – this is the highest percentage expressing this sentiment since the early 1990s.

As might be expected, there are substantial socioeconomic differences in these attitudes, though they have not widened over the years. In the current survey, fully 75% of those in the lowest income category say they do not have enough money to make ends meet, compared with just 20% of those in the upper-income group.

Fewer See Unlimited Growth

As the public’s personal financial assessments have become more negative, so too have its views of the country’s growth prospects. Only about half (51%) agree that “I don’t believe there are any real limits to growth in this country today,” while 45% disagree. The percentage agreeing that there are no limits to growth (51%) is the lowest ever.

As the public’s personal financial assessments have become more negative, so too have its views of the country’s growth prospects. Only about half (51%) agree that “I don’t believe there are any real limits to growth in this country today,” while 45% disagree. The percentage agreeing that there are no limits to growth (51%) is the lowest ever.

There are only modest demographic differences in these opinions. Comparable percentages of college graduates (47%), those with some college experience (52%) and those with a high school education or less (54%) say that there are no limits to growth.

Despite the public’s declining belief in the potential for unlimited growth, it has not grown skeptical of Americans’ abilities to solve problems. The percentage agreeing “as Americans we can always find a way to solve our problems and get what we want” is as high today as it was in the first political values survey in 1987 (69% now, 68% then).

Poor people are less likely than those with higher incomes to express optimism about Americans’ abilities to solve problems. Still, majorities across most demographic groups – including 57% of those in the lowest income quartile – say the American people can solve their problems.

Partisan differences in opinions about the ability of the American people to solve their problems have fluctuated in recent years. In the current survey, 77% of Republicans agree, compared with 71% of independents and 64% of Democrats.

Partisan differences in opinions about the ability of the American people to solve their problems have fluctuated in recent years. In the current survey, 77% of Republicans agree, compared with 71% of independents and 64% of Democrats.

In 2009, there were virtually no partisan differences in these views. But in 2007, the partisan gap was much wider than it is today; at that time, 72% of Republicans expressed confidence in the people’s ability to solve problems, compared with 56% of independents and 53% of Democrats.

Most Upsetting: Cheating Gov’t Out of Benefits

The political values survey also asked about reactions to some illegal or morally questionable behaviors. Overall, far more Americans (70%) say they would be very upset if they heard someone claimed government benefits that they were not entitled to than if they heard a person had not paid all the taxes they owed (45%).

The political values survey also asked about reactions to some illegal or morally questionable behaviors. Overall, far more Americans (70%) say they would be very upset if they heard someone claimed government benefits that they were not entitled to than if they heard a person had not paid all the taxes they owed (45%).

Other behaviors are viewed as less upsetting, including using government food aid for candy or soda (39% very upset), stopping payments on an underwater mortgage (31%), or parents not attending their child’s parent-teacher conferences (30%).

Most Americans find all of these behaviors unacceptable; majorities say they would either be very upset or just annoyed over hearing about each one. No more than a third say they either wouldn’t care about or would approve of any of these behaviors.

Most Americans find all of these behaviors unacceptable; majorities say they would either be very upset or just annoyed over hearing about each one. No more than a third say they either wouldn’t care about or would approve of any of these behaviors.

There are sizable partisan differences in reactions to many of these practices. Nearly half of Republicans (46%) say they would be very upset if they heard someone had stopped making mortgage payments on a house worth less than what they owe; fewer independents (28%) and Democrats (25%) find this very upsetting.

Republicans also are more likely than Democrats to be very upset by someone claiming government benefits illegitimately (by 15 points) and using government food aid to buy candy and soda (13 points).

There are racial divides in these concerns. Whites are more likely than blacks or Hispanics to say someone claiming government benefits they were not entitled to is very upsetting –  though majorities in all groups express this view. Both whites and Hispanics react more negatively than do blacks to using government food aid to purchase candy or soda. And when it comes to a parent missing their child’s teacher conference, Hispanics and blacks find this more upsetting than do whites.

though majorities in all groups express this view. Both whites and Hispanics react more negatively than do blacks to using government food aid to purchase candy or soda. And when it comes to a parent missing their child’s teacher conference, Hispanics and blacks find this more upsetting than do whites.

But there is little evidence of significant class differences among whites in reactions to these behaviors. Lower-income whites find four of the five items just as upsetting as do higher income whites. The one exception is walking away from an underwater mortgage, which whites with household incomes under $75,000 find less upsetting than higher income whites.

Slideshow

Slideshow Interactive

Interactive