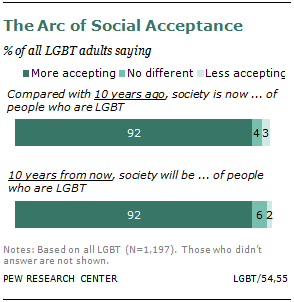

An overwhelming share of America’s lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender adults (92%) say society has become more accepting of them in the past decade and an equal number expect it to grow even more accepting in the decade ahead. They attribute the changes to a variety of factors, from people knowing and interacting with someone who is LGBT, to advocacy on their behalf by high-profile public figures, to LGBT adults raising families.1

An overwhelming share of America’s lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender adults (92%) say society has become more accepting of them in the past decade and an equal number expect it to grow even more accepting in the decade ahead. They attribute the changes to a variety of factors, from people knowing and interacting with someone who is LGBT, to advocacy on their behalf by high-profile public figures, to LGBT adults raising families.1

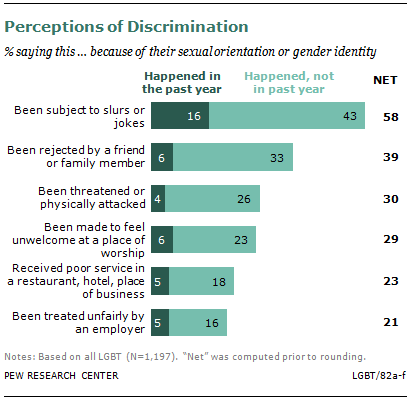

At the same time, however, a new nationally representative survey of 1,197 LGBT adults offers testimony to the many ways they feel they have been stigmatized by society. About four-in-ten (39%) say that at some point in their lives they were rejected by a family member or close friend because of their sexual orientation or gender identity; 30% say they have been physically attacked or threatened; 29% say they have been made to feel unwelcome in a place of worship; and 21% say they have been treated unfairly by an employer. About six-in-ten (58%) say they’ve been the target of slurs or jokes.

At the same time, however, a new nationally representative survey of 1,197 LGBT adults offers testimony to the many ways they feel they have been stigmatized by society. About four-in-ten (39%) say that at some point in their lives they were rejected by a family member or close friend because of their sexual orientation or gender identity; 30% say they have been physically attacked or threatened; 29% say they have been made to feel unwelcome in a place of worship; and 21% say they have been treated unfairly by an employer. About six-in-ten (58%) say they’ve been the target of slurs or jokes.

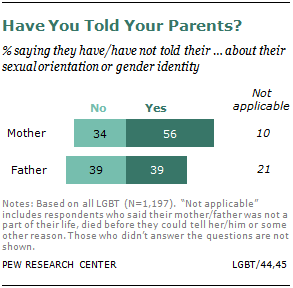

Also, just 56% say they have told their mother about their sexual orientation or gender identity, and 39% have told their father. Most who did tell a parent say that it was difficult, but relatively few say that it damaged their relationship.

Also, just 56% say they have told their mother about their sexual orientation or gender identity, and 39% have told their father. Most who did tell a parent say that it was difficult, but relatively few say that it damaged their relationship.

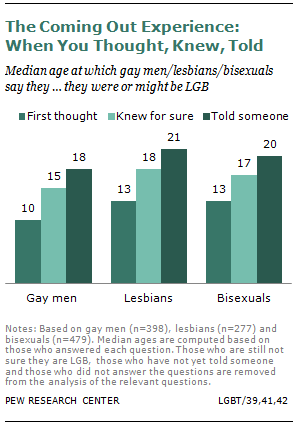

The survey finds that 12 is the median age at which lesbian, gay and bisexual adults first felt they might be something other than heterosexual or straight. For those who say they now know for sure that they are lesbian, gay, bisexual or transgender, that realization came at a median age of 17.

Among those who have shared this information with a family member or close friend, 20 is the median age at which they first did so.

Among those who have shared this information with a family member or close friend, 20 is the median age at which they first did so.

Gay men report having reached all of these coming out milestones somewhat earlier than do lesbians and bisexuals.

The survey was conducted April 11-29, 2013, and administered online, a survey mode that research indicates tends to produce more honest answers on a range of sensitive topics than do other less anonymous modes of survey-taking. For more details, see Chapter 1 and Appendix 1.

The survey finds that the LGBT population is distinctive in many ways beyond sexual orientation. Compared with the general public, Pew Research LGBT survey respondents are more liberal, more Democratic, less religious, less happy with their lives, and more satisfied with the general direction of the country. On average, they are younger than the general public. Their family incomes are lower, which may be related to their relative youth and the smaller size of their households. They are also more likely to perceive discrimination not just against themselves but also against other groups with a legacy of discrimination.

About the Survey

Findings in this report are based on two main data sources:

This report is based primarily on a Pew Research Center survey of the LGBT population conducted April 11-29, 2013, among a nationally representative sample of 1,197 self-identified lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender adults 18 years of age or older. The sample comprised 398 gay men, 277 lesbians, 479 bisexuals and 43 transgender adults. The survey questionnaire was written by the Pew Research Center and administered by the GfK Group using KnowledgePanel, its nationally representative online research panel.

The online survey mode was chosen for this study, in part, because considerable research on sensitive issues (such as drug use, sexual behavior and even attendance at religious services) indicates that the online mode of survey administration is likely to elicit more honest answers from respondents on a range of topics.

The margin of sampling error for the full LGBT sample is plus or minus 4.1 percentage points at the 95% confidence level. For more details on the LGBT survey methodology, see Appendix 1.

In most cases the comparisons made between LGBT adults and the general public are taken from other Pew Research Center surveys.

Same-Sex Marriage

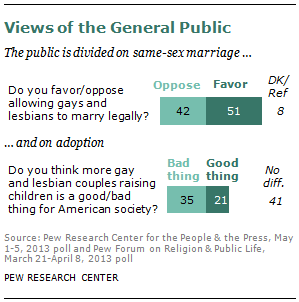

On the topic of same-sex marriage, not surprisingly, there is a large gap between the views of the general public and those of LGBT adults. Even though a record 51% of the public now favors allowing gays and lesbians to marry legally, up from 32% in 2003, that share is still far below the 93% of LGBT adults who favor same-sex marriage.

Despite nearly universal support for same-sex marriage among LGBT adults, a significant minority of that population—39%—say that the issue has drawn too much attention away from other issues that are important to people who are LGBT. However, 58% say it should be the top priority even if it takes attention away from other issues.

The survey finds that 16% of LGBT adults—mostly bisexuals with opposite-sex partners—are currently married, compared with about half the adults in the general public. Overall, a total of 60% of LGBT survey respondents are either married or say they would like to marry one day, compared with 76% of the general public.

Large majorities of LGBT adults and the general public agree that love, companionship and making a lifelong commitment are very important reasons to marry. However LGBT survey respondents are twice as likely as those in the general public to say that obtaining legal rights and benefits is also a very important reason to marry (46% versus 23%). And the general public is more likely than LGBT respondents to say that having children is a very important reason to marry (49% versus 28%).

The LGBT Population and its Sub-Groups

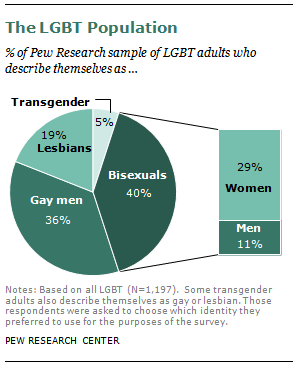

Four-in-ten respondents to the Pew Research Center survey identify themselves as bisexual. Gay men are 36% of the sample, followed by lesbians (19%) and transgender adults (5%).2 While these shares are consistent with findings from other surveys of the LGBT population, they should be treated with caution.3 There are many challenges in estimating the size and composition of the LGBT population, starting with the question of whether to use a definition based solely on self-identification (the approach taken in this report) or whether to also include measures of sexual attraction and sexual behavior.

Four-in-ten respondents to the Pew Research Center survey identify themselves as bisexual. Gay men are 36% of the sample, followed by lesbians (19%) and transgender adults (5%).2 While these shares are consistent with findings from other surveys of the LGBT population, they should be treated with caution.3 There are many challenges in estimating the size and composition of the LGBT population, starting with the question of whether to use a definition based solely on self-identification (the approach taken in this report) or whether to also include measures of sexual attraction and sexual behavior.

This report makes no attempt to estimate the share of the U.S. population that is LGBT. Other recent survey-based research reports have made estimates in the 3.5% to 5% range. However, all such estimates depend to some degree on the willingness of LGBT individuals to disclose their sexual orientation and gender identity, and research suggests that not everyone in this population is ready or willing to do so. (See Appendix 1 for a discussion of these and other methodological issues).

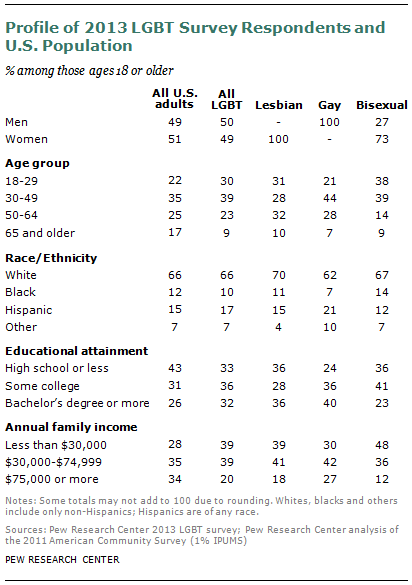

The table above provides a look at key demographic characteristics of the full Pew Research LGBT survey sample and its three largest sub-groups—bisexuals, gay men and lesbians. It shows, among other things, that bisexuals are younger, have lower family incomes and are less likely to be college graduates than gay men and lesbians. The relative youth of bisexuals likely explains some of their lower levels of income and education.

The table above provides a look at key demographic characteristics of the full Pew Research LGBT survey sample and its three largest sub-groups—bisexuals, gay men and lesbians. It shows, among other things, that bisexuals are younger, have lower family incomes and are less likely to be college graduates than gay men and lesbians. The relative youth of bisexuals likely explains some of their lower levels of income and education.

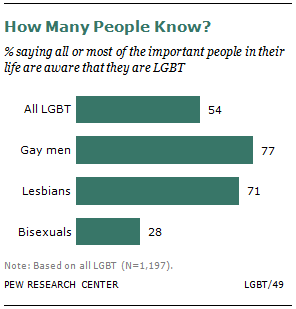

The survey also finds that bisexuals differ from gay men and lesbians on a range of attitudes and experiences related to their sexual orientation. For example, while 77% of gay men and 71% of lesbians say most or all of the important people in their lives know of their sexual orientation, just 28% of bisexuals say the same. Bisexual women are more likely to say this than bisexual men (33% vs. 12%). Likewise, about half of gay men and lesbians say their sexual orientation is extremely or very important to their overall identity, compared with just two-in-ten bisexual men and women.

The survey also finds that bisexuals differ from gay men and lesbians on a range of attitudes and experiences related to their sexual orientation. For example, while 77% of gay men and 71% of lesbians say most or all of the important people in their lives know of their sexual orientation, just 28% of bisexuals say the same. Bisexual women are more likely to say this than bisexual men (33% vs. 12%). Likewise, about half of gay men and lesbians say their sexual orientation is extremely or very important to their overall identity, compared with just two-in-ten bisexual men and women.

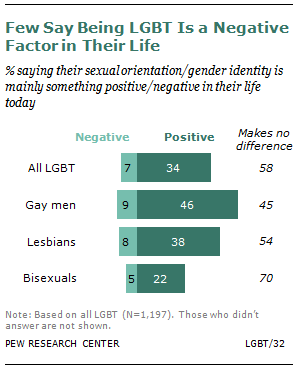

Gays and lesbians are also more likely than bisexuals to say their sexual orientation is a positive factor in their lives, though across all three subgroups, many say it is neither positive nor negative. Only a small fraction of all groups describe their sexual orientation or gender identity as a negative factor.

Gays and lesbians are also more likely than bisexuals to say their sexual orientation is a positive factor in their lives, though across all three subgroups, many say it is neither positive nor negative. Only a small fraction of all groups describe their sexual orientation or gender identity as a negative factor.

Roughly three-quarters of bisexual respondents to the Pew Research survey are women. By contrast, gay men outnumber lesbians by about two-to-one among survey respondents. Bisexuals are far more likely than either gay men or lesbians to be married, in part because a large majority of those in committed relationships have partners of the opposite sex and thus are able to marry legally. Also, two-thirds of bisexuals say they either already have or want children, compared with about half of lesbians and three-in-ten gay men.

Across the LGBT population, more say bisexual women and lesbians are accepted by society than say this about gay men, bisexual men or transgender people. One-in-four respondents say there is a lot of social acceptance of lesbians, while just 15% say the same about gay men. Similarly, there is more perceived acceptance of bisexual women (33% a lot) than of bisexual men (8%). Transgender adults are viewed as less accepted by society than other LGBT groups: only 3% of survey respondents say there is a lot of acceptance of this group.

Social Acceptance and the Public’s Perspective

Even though most LGBT adults say there has been significant progress toward social acceptance, relatively few (19%) say there is a lot of social acceptance for the LGBT population today. A majority (59%) says there is some, and 21% say there is little or no acceptance today.

Surveys of the general public show that societal acceptance is on the rise. More Americans now say they favor same-sex marriage and fewer say homosexuality should be discouraged, compared with a decade ago. These changing attitudes may be due in part to the fact that a growing share of all adults say they personally know someone who is gay or lesbian—87% today, up from 61% in 1993.

A new Pew Research Center analysis shows that among the general public, knowing someone who is gay or lesbian is linked with greater acceptance of homosexuality and support for same-sex marriage.

LGBT adults themselves recognize the value of these personal interactions; 70% say people knowing someone who is LGBT helps a lot in terms of making society more accepting of the LGBT population.

Still, a significant share of the public believes that homosexuality should be discouraged and that same-sex marriage should not be legal. Much of this resistance is rooted in deeply held religious attitudes, such as the belief that engaging in homosexual behavior is a sin.

Still, a significant share of the public believes that homosexuality should be discouraged and that same-sex marriage should not be legal. Much of this resistance is rooted in deeply held religious attitudes, such as the belief that engaging in homosexual behavior is a sin.

And the public is conflicted about how the rising share of gays and lesbians raising children is affecting society. Only 21% of all adults say this trend is a good thing for society, 35% say this is a bad thing for society, and 41% say it doesn’t make much difference. The share saying this is a bad thing has fallen significantly in recent years (from 50% in 2007).

The Coming Out Process

In the context of limited but growing acceptance of the LGBT population, many LGBT adults have struggled with how and when to tell others about their sexual orientation. About six-in-ten (59%) have told one or both of their parents, and a majority say most of the people who are important to them know about this aspect of their life.

Most of those who have told their parents say this process wasn’t easy. Some 59% of those who have told their mother about their sexual orientation or gender identity and 65% who have told their father say it was difficult to share this information. However, of those who have told their mothers, the vast majority say it either made the relationship stronger (39%) or didn’t change the relationship (46%). A similar-sized majority says telling their father about their sexual orientation or gender identity didn’t hurt their relationship.

Age, Gender and Race

The survey finds that the attitudes and experiences of younger adults into the LGBT population differ in a variety of ways from those of older adults, perhaps a reflection of the more accepting social milieu in which younger adults have come of age.

For example, younger gay men and lesbians are more likely to have disclosed their sexual orientation somewhat earlier in life than have their older counterparts. Some of this difference may be attributable to changing social norms, but some is attributable to the fact that the experiences of young adults who have not yet identified as being gay or lesbian but will do so later in life cannot be captured in this survey.

As for gender patterns, the survey finds that lesbians are more likely than gay men to be in a committed relationship (66% versus 40%); likewise, bisexual women are much more likely than bisexual men to be in one of these relationships (68% versus 40%). In addition women, whether lesbian or bisexual, are significantly more likely than men to either already have children or to say they want to have children one day.

Among survey respondents, whites are more likely than non-whites to say society is a lot more accepting of LGBT adults now than it was a decade ago (58% vs. 42%) and, by a similar margin, are more optimistic about future levels of acceptance.4 Non-whites are more likely than whites to say being LGBT is extremely or very important to their overall identity (44% versus 34%) and more likely as well to say there is a conflict between their religion and their sexual orientation (37% versus 20%).

Views of Issues, Leaders, Institutions

On the eve of a ruling expected later this month by the U.S. Supreme Court on two same-sex marriage cases, 58% of LGBT adults say they have a favorable view of the court and 40% view it unfavorably; these assessments are similar to those held by the general public.

On the eve of a ruling expected later this month by the U.S. Supreme Court on two same-sex marriage cases, 58% of LGBT adults say they have a favorable view of the court and 40% view it unfavorably; these assessments are similar to those held by the general public.

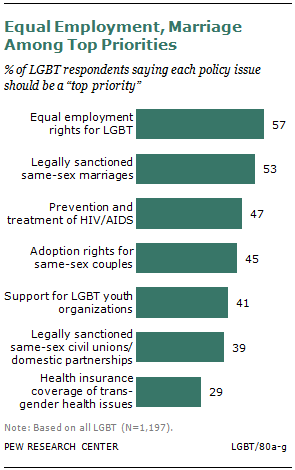

While the same-sex marriage issue has dominated news coverage of the LGBT population in recent years, it is only one of several top priority issues identified by survey respondents. Other top rank issues include employment rights, HIV and AIDS prevention and treatment, and adoption rights.

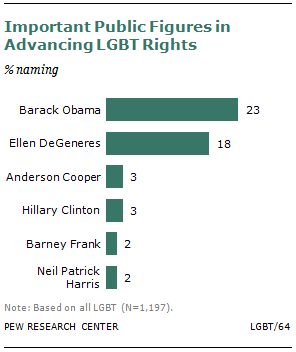

When asked in an open-ended question to name the national public figures most responsible for advancing LGBT rights, President Barack Obama, who announced last year that he had changed his mind and supports gay marriage, tops the list along with comedian and talk show host Ellen DeGeneres, who came out as a lesbian in 1997 and has been a leading advocate for the LGBT population ever since then. Some 23% of respondents named Obama and 18% named DeGeneres. No one else was named by more than 3% of survey respondents.

When asked in an open-ended question to name the national public figures most responsible for advancing LGBT rights, President Barack Obama, who announced last year that he had changed his mind and supports gay marriage, tops the list along with comedian and talk show host Ellen DeGeneres, who came out as a lesbian in 1997 and has been a leading advocate for the LGBT population ever since then. Some 23% of respondents named Obama and 18% named DeGeneres. No one else was named by more than 3% of survey respondents.

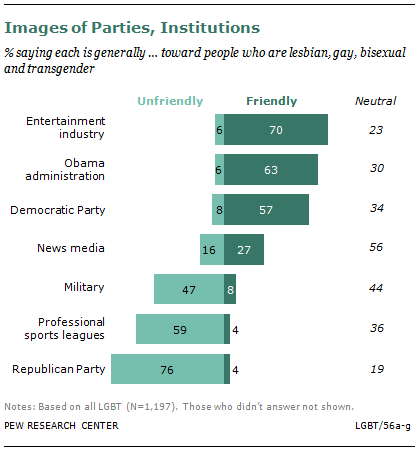

For the most part LGBT adults are in broad agreement on which institutions they consider friendly to people who are lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender. Seven-in-ten describe the entertainment industry as friendly, 63% say the same about the Obama administration, and 57% view the Democratic Party as friendly. By contrast, just 4% say the same about the Republican Party (compared with 76% who say it is unfriendly); 8% about the military (47% unfriendly) and 4% about professional sports leagues (59% unfriendly). LGBT adults have mixed views about the news media, with 27% saying it is friendly, 56% neutral and 16% unfriendly.

For the most part LGBT adults are in broad agreement on which institutions they consider friendly to people who are lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender. Seven-in-ten describe the entertainment industry as friendly, 63% say the same about the Obama administration, and 57% view the Democratic Party as friendly. By contrast, just 4% say the same about the Republican Party (compared with 76% who say it is unfriendly); 8% about the military (47% unfriendly) and 4% about professional sports leagues (59% unfriendly). LGBT adults have mixed views about the news media, with 27% saying it is friendly, 56% neutral and 16% unfriendly.

LGBT survey respondents are far more Democratic than the general public—about eight-in-ten (79%) are Democrats or lean to the Democratic Party, compared with 49% of the general public. And they offer opinions on a range of public policy issues that are in sync with the Democratic and liberal tilt to their partisanship and ideology. For example, they are more likely than the general public to say they support a bigger government that provides more services (56% versus 40%); they are more supportive of gun control (64% versus 50%) and they are more likely to say immigrants strengthen the country (62% versus 49%).

Self and Country

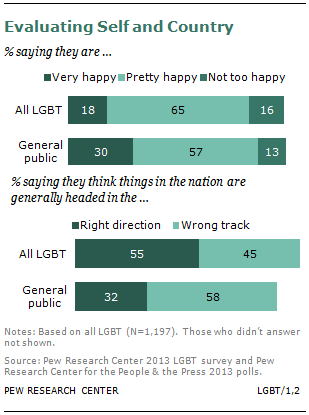

LGBT adults and the general public are also notably different in the ways they evaluate their personal happiness and the overall direction of the country.

LGBT adults and the general public are also notably different in the ways they evaluate their personal happiness and the overall direction of the country.

In the case of happiness, just 18% of LGBT adults describe themselves as “very happy,” compared with 30% of adults in the general public who say the same. Gay men, lesbians and bisexuals are roughly equal in their expressed level of happiness.

When it comes to evaluations of the direction of the nation, the pattern reverses, with LBGT adults more inclined than the general public (55% versus 32%) to say the country is headed in the right direction. Opinions on this question are strongly associated with partisanship.

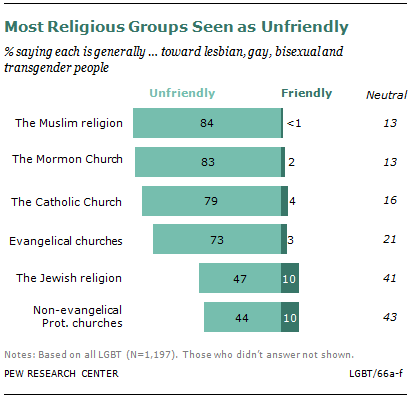

Religion

Religion is a difficult terrain for many LGBT adults. Lopsided majorities describe the Muslim religion (84%), the Mormon Church (83%), the Catholic Church (79%) and evangelical churches (73%) as unfriendly toward people who are LGBT. They have more mixed views of the Jewish religion and mainline Protestant churches, with fewer than half of LGBT adults describing those religions as unfriendly, one-in-ten describing each of them as friendly and the rest saying they are neutral.

The survey finds that LGBT adults are less religious than the general public. Roughly half (48%) say they have no religious affiliation, compared with 20% of the public at large. Of those LGBT adults who are religiously affiliated, one-third say there is a conflict between their religious beliefs and their sexual orientation or gender identity. And among all LGBT adults, about three-in-ten (29%) say they have been made to feel unwelcome in a place of worship.

Pew Research surveys of the general public show that while societal views about homosexuality have shifted dramatically over the past decade, highly religious Americans remain more likely than others to believe that homosexuality should be discouraged rather than accepted by society. And among those who attend religious services weekly or more frequently, fully two-thirds say that homosexuality conflicts with their religious beliefs (with 50% saying there is a great deal of conflict). In addition, religious commitment is strongly correlated with opposition to same-sex marriage.

Pew Research surveys of the general public show that while societal views about homosexuality have shifted dramatically over the past decade, highly religious Americans remain more likely than others to believe that homosexuality should be discouraged rather than accepted by society. And among those who attend religious services weekly or more frequently, fully two-thirds say that homosexuality conflicts with their religious beliefs (with 50% saying there is a great deal of conflict). In addition, religious commitment is strongly correlated with opposition to same-sex marriage.

Community Identity and Engagement

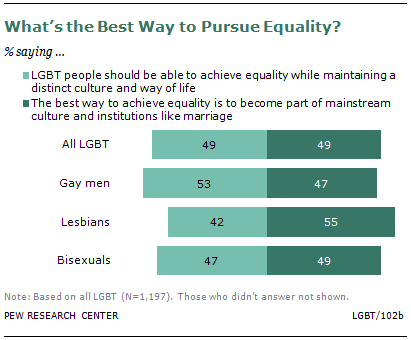

As LGBT adults become more accepted by society, the survey finds different points of view about how fully they should seek to become integrated into the broader culture. About half of survey respondents (49%) say the best way to achieve equality is to become a part of mainstream culture and institutions such as marriage, but an equal share say LGBT adults should be able to achieve equality while still maintaining their own distinct culture and way of life.

As LGBT adults become more accepted by society, the survey finds different points of view about how fully they should seek to become integrated into the broader culture. About half of survey respondents (49%) say the best way to achieve equality is to become a part of mainstream culture and institutions such as marriage, but an equal share say LGBT adults should be able to achieve equality while still maintaining their own distinct culture and way of life.

Likewise, there are divisions between those who say it is important to maintain places like LGBT neighborhoods and bars (56%) and those who feel these venues will become less important over time (41%). Gay men are most likely of any of the LGBT subgroups to say that these distinctive venues should be maintained (68%).

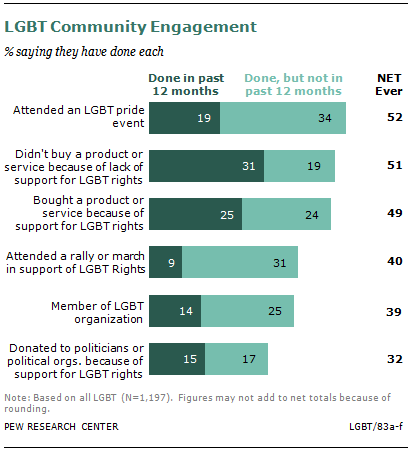

When it comes to community engagement, gay men and lesbians are more involved than bisexuals in a variety of LGBT-specific activities, such as attending a gay pride event or being a member of an LGBT organization.

When it comes to community engagement, gay men and lesbians are more involved than bisexuals in a variety of LGBT-specific activities, such as attending a gay pride event or being a member of an LGBT organization.

Overall, many LGBT adults say they have used their economic power in support or opposition to certain products or companies. About half (51%) say they have not bought a product or service because the company that provides it is not supportive of LGBT rights. A similar share (49%) says they have specifically bought a product or service because the company is supportive of LGBT rights.

Some 52% have attended an LGBT pride event, and 40% have attended a rally or march in support of LGBT rights. About four-in-ten (39%) say they belong to an LGBT organization and roughly three-in-ten (31%) have donated money to politicians who support their rights.

LGBT Adults Online

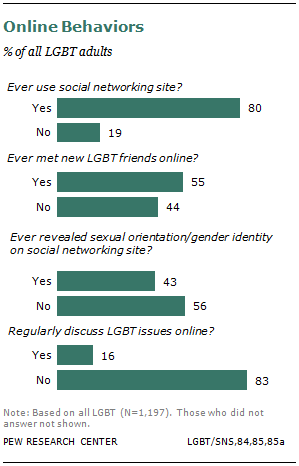

LGBT adults are heavy users of social networking sites, with 8o% of survey respondents saying they have used a site such as Facebook or Twitter. This compares with 58% of the general public (and 68% of all internet users), a gap largely attributable to the fact that as a group LGBT adults are younger than the general public, and young adults are much more likely than older adults to use social networking sites. When young LGBT adults are compared with all young adults, the share using these sites is almost identical (89% of LGBT adults ages 18 to 29 vs. 90% of all adults ages 18 to 29).

LGBT adults are heavy users of social networking sites, with 8o% of survey respondents saying they have used a site such as Facebook or Twitter. This compares with 58% of the general public (and 68% of all internet users), a gap largely attributable to the fact that as a group LGBT adults are younger than the general public, and young adults are much more likely than older adults to use social networking sites. When young LGBT adults are compared with all young adults, the share using these sites is almost identical (89% of LGBT adults ages 18 to 29 vs. 90% of all adults ages 18 to 29).

There are big differences across LGBT groups in how they use social networking sites. Among all LGBT adults, 55% say they have met new LGBT friends online or through a social networking site. Gay men are the most likely to say they have done this (69%). By contrast, about half of lesbians (47%) and bisexuals (49%) say they have met a new LGBT friend online.

About four-in-ten LGBT adults (43%) have revealed their sexual orientation or gender identity on a social networking site. While roughly half of gay men and lesbians have come out on a social network, only about one-third (34%) of bisexuals say they have done this.

Just 16% say they regularly discuss LGBT issues online; 83% say they do not do this.

A Note on Transgender Respondents

Transgender is an umbrella term that groups together a variety of people whose gender identity or gender expression differs from their birth sex. Some identify as female-to-male, others as male-to-female. Others may call themselves gender non-conforming, reflecting an identity that differs from social expectations about gender based on birth sex. Some may call themselves genderqueer, reflecting an identity that may be neither male nor female. And others may use the term transsexual to describe their identity. A transgender identity is not dependent upon medical procedures. While some transgender individuals may choose to alter their bodies through surgery or hormonal therapy, many transgender people choose not to do so.

People who are transgender may also describe themselves as heterosexual, gay, lesbian, or bisexual. In the Pew Research Center survey, respondents were asked whether they considered themselves to be transgender in a separate series of questions from the question about whether they considered themselves to be lesbian, gay, bisexual, or heterosexual (see Appendix 1 for more details).

The Pew Research survey finds that 5% of LGBT respondents identify primarily as transgender; this is roughly consistent with other estimates of the proportion of the LGBT population that is transgender. Although there is limited data on the size of the transgender population, it is estimated that 0.3% of all American adults are transgender (Gates 2011).

Because of the small number of transgender respondents in this survey (n=43), it is not possible to generate statistically significant findings about the views of this subgroup. However, their survey responses are represented in the findings about the full LGBT population throughout the survey.

The responses to both open- and closed-ended questions do allow for a few general findings. For example, among transgender respondents to this survey, most say they first felt their gender was different from their birth sex before puberty. For many, being transgender is a core part of their overall identity, even if they may not widely share this with many people in their lives.

And just as gay men, lesbians, and bisexuals perceive less commonality with transgender people than with each other, transgender adults may appear not to perceive a great deal of commonality with lesbians, gay men, and bisexuals. In particular, issues like same-sex marriage may be viewed as less important by this group, and transgender adults appear to be less involved in the LGBT community than are other sub-groups.

Here are some of the voices of transgender adults in the survey:

Voices: Transgender Survey Respondents

On Gender Identity

“It finally feels comfortable to be in my own body and head—I can be who I am, finally.”

–Transgender adult, age 24

“I have suffered most of my life in the wrong gender. Now I feel more at home in the world, though I must admit, not completely. There is still plenty of phobic feeling.”

–Transgender adult, age 77

“Though I have not transitioned fully, being born as male but viewing things from a female perspective gives me a perspective from both vantage points. I am very empathetic because of my circumstance.”

–Transgender adult, age 56

“I wish I could have identified solely as male. Identifying as another gender is not easy.”

–Transgender adult, age 49

On Telling People

“Times were different for in-between kids born in the 30’s. We mostly tried to conform and simply lived two lives at once. The stress caused a very high suicide rate and a higher rate of alcohol addiction (somehow I was spared both.)”

-Transgender adult, age 77

“It’s been hard and very cleansing at the same time. The hardest part is telling old friends because they’ve known you for so long as your born gender. But most people are willing to change for you if they care enough.” –Transgender adult, age 27

“I have only told close members of my family and only a handful of friends. I don’t think that it is important to shout it out from the rooftops, especially in my profession.”

–Transgender adult, age 38

“This process is difficult. Most people know me one way and to talk to them about a different side of me can be disconcerting. I have not told most people because of my standing in the community and my job, which could be in jeopardy”

–Transgender adult, age 44

“Some of my family still refers to me as “she” but when we go out they catch themselves because of how I look, they sound foolish to strangers :). When it’s a bunch of family or old friends, they usually don’t assign me a gender they say my name. But I don’t get too bothered by it, they are family and well, that’s a huge thing to have to change in your mind. For the ones that do it out of disrespect, I just talk to them one on one and ask for them to do better.” –Transgender adult, age 29

LGBT/32a,50

Interactive: LGBT Voices

Explore some 300 quotes from LGBT survey respondents about their coming out experiences.

Notes on Terminology

Unless otherwise noted, all references to whites, blacks and others are to the non-Hispanic components of those populations. Hispanics can be of any race. Non-whites refers to people whose race is not white (e.g. black, Asian, etc.) or to Hispanics regardless of their race.

Throughout this report, the acronym “LGBT” is used to refer to the lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender population. The phrases “LGBT adults,” “LGBT individuals,” “LGBT people” and “LGBT respondents” are used interchangeably throughout this report as are the phrases “LGBT population” and “LGBT community.”

In the survey instrument, when LGBT adults were asked about their identity, gays, lesbians and bisexuals were asked about their sexual orientation while transgender respondents were asked about their gender identity. This protocol is also used in the report when reporting LGBT adults’ views of their identity.

References to the political party identification of respondents include those who identify with a political party or lean towards a specific political party. Those identified as independents do not lean towards either the Democratic Party or the Republican Party.

Acknowledgments

Many Pew Research Center staff members contributed to this research project. Paul Taylor oversaw the project and served as lead editor of the report. Kim Parker, Jocelyn Kiley and Mark Hugo Lopez took the lead in the development of the LGBT survey instrument. Scott Keeter managed development of the survey’s methodological strategy.

The report’s overview was written by Taylor. Chapter 1 of the report was written by D’Vera Cohn and Gretchen Livingston. Parker wrote chapters 2 and 3. Chapter 4 was written by Eileen Patten. Chapter 5 was written by Kiley and Patten. Cary Funk and Rich Morin wrote Chapter 6 of the report. Kiley wrote Chapter 7. Keeter wrote the report’s methodology appendix. Lopez, Patten, Kiley, Sara Goo, Adam Nekola and Meredith Dost curated quotes for the “voices” features and online interactive. The report was number checked by Anna Brown, Danielle Cuddington, Matthew Frei, Seth Motel, Patten, Rob Suls, Alec Tyson and Wendy Wang. Noble Kuriakose and Besheer Mohamed provided data analysis for the report’s demographic chapter. The report was copy-edited by Marcia Kramer of Kramer Editing Services and Molly Rohal.

Others at the Pew Research Center who provided editorial or research guidance include Alan Murray, Michael Dimock, Carroll Doherty, Andrew Kohut, Alan Cooperman, Lee Rainie and James Hawkins.

Staffers who helped to disseminate the report and to prepare related online content include Goo, Vidya Krishnamurthy, Michael Piccorossi, Russ Oates, Adam Nekola, Diana Yoo, Michael Suh, Andrea Caumont, Michael Keegan, Jessica Schillinger, Bruce Drake, Caroline Klibanoff, Rohal, Russell Heimlich and Katie Reilly.

The Pew Research Center thanks and acknowledges M.V. Lee Badgett and Gary J. Gates. Badgett is the Director of the Center for Public Policy & Administration and Professor of economics at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst. She is also the research director of UCLA’s Williams Institute. Gates is the Williams Distinguished Scholar at UCLA’s Williams Institute. They served as advisors to the project, providing invaluable guidance on survey questionnaire development, demographic analysis of U.S. Census Bureau data and the survey’s methodology. We also thank Stephanie Jwo, Joseph Garrett and Monsour Fahimi of the GfK Group, who worked with Keeter on the survey’s sampling design, data collection protocol and weighting plan and oversaw the collection of the data; and Frank Newport of Gallup, who provided comparative data from Gallup’s surveys.

The Pew Research Center conducted a focus group discussion on March 26, 2013 in Washington, D.C. to help inform the survey questionnaire’s development. The focus group was moderated by Lopez and was composed of 12 individuals ages 18 and older. Participants were told that what they said might be quoted in the report or other products from the Pew Research Center, but that they would not be identified by name.

Roadmap to the Report

Chapter 1, Demographic Portrait and Research Challenges, examines the demographic profile of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender adults surveyed by the Pew Research Center and other prominent research organizations. It also includes data on same-sex couples from the U.S. Census Bureau. In addition, this chapter discusses the challenges involved in surveying this population and making estimates about its size and characteristics.

Chapter 2, Social Acceptance, looks at societal views of the LGBT population from the perspective of LGBT adults themselves. It also chronicles the ways in which LGBT adults have experienced discrimination in their own lives and looks at the extent to which they believe major institutions in this country are accepting of them.

Chapter 3, The Coming Out Experience, chronicles the journey LGBT adults have been on in realizing their sexual orientation or gender identity and sharing that information with family and friends. It also looks at where LGBT adults live, how many of their friends are LGBT and whether they are open about their LGBT identity at work. This chapter includes a brief section on online habits and behaviors.

Chapter 4, Marriage and Parenting, looks at LGBT adults’ attitudes toward same-sex marriage and also their experiences in the realm of family life. It examines their relationship status and their desire to marry and have children—detailing the key differences across LGBT groups and between LGBT adults and the general public.

Chapter 5, Identity and Community, explores how LGBT adults view their sexual orientation or gender identity in the context of their overall identity. It looks at the extent to which this aspect of their lives is central to who they are, as well as how much they feel they have in common with other LGBT adults. It also looks at the extent to which LGBT adults are engaged in the broader LGBT community and how they view the balance between maintaining a distinct LGBT culture and becoming part of the American mainstream.

Chapter 6, Religion, details the religious affiliation, beliefs and practices of LGBT adults and compares them with those of the general public. It also looks at whether LGBT adults feel their religious beliefs are in conflict with their sexual orientation or gender identity, and how they feel they are perceived by various religious groups and institutions.

Chapter 7, Partisanship, Policy Views, Values, looks at the party affiliation of LGBT adults and their views of Barack Obama and of the Democratic and Republican parties. It also includes LGBT views on key policy issues, such as immigration and gun control, and compares them with those of the general public. And it also looks at how LGBT adults prioritize LGBT-related policy issues beyond same-sex marriage.

Following the survey chapters is a detailed survey methodology statement. This includes descriptions of the sampling frame, questionnaire development and weighting procedures for the LGBT survey. It also has a demographic profile of the Pew Research LGBT survey respondents with details on specific LGBT groups.

Interspersed throughout the report are Voices of LGBT adults. These are quotes from open-ended questions included in the survey and are meant to personalize the aggregate findings and add richness and nuance. Individual respondents are identified only by their age, gender and sexual orientation or gender identity. Additional quotes from LGBT respondents are available in an interactive feature on the Pew Research Center website.

Charts: Personal Milestones in the Coming Out Experience

Charts: Personal Milestones in the Coming Out Experience