This report provides state by state estimates for the educational profile of voters in the 2004, 2008, 2012 and 2016 U.S. presidential elections. Estimates are based on an analysis of the Current Population Survey (CPS) Voting and Registration Supplements conducted by the U.S. Census Bureau for each of those years. The CPS is administered using in-person and live telephone interviewing. Households are selected using a national sample of addresses produced through a stratified, multi-stage sample design.

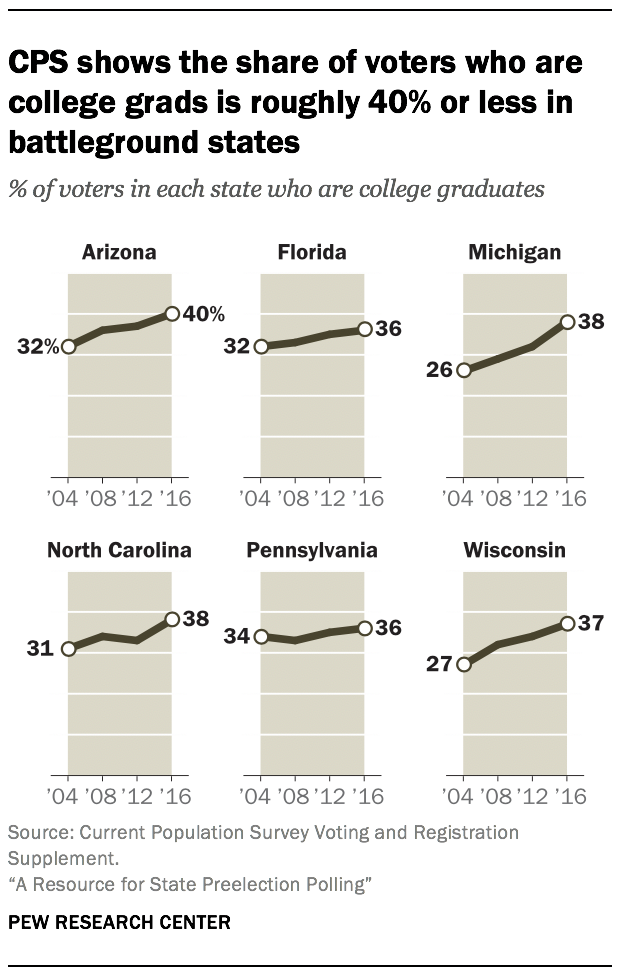

Post-mortem analysis of the 2016 election found that a failure to adjust for overrepresentation of college graduates was among the reasons many state-level polls underestimated support for Donald Trump. Voters who graduated from a four-year college are more likely to answer surveys than other adults and, in recent years, they are also more likely to support a Democrat for president. If a battleground state poll does not adjust for having too many college graduates, it is at risk of overstating support for a Democratic presidential candidate (in this case, Joe Biden).

Since 2016, many pollsters heeded this lesson and added an education adjustment to their work. Additionally, most national pollsters as well as some state pollsters had been making the adjustment for many election cycles and continue to do so. But not all have fixed this issue. For example, a June poll appeared to show Biden with a massive 18-percentage-point lead in Michigan. But a look at the sample shows why: More than two-thirds (69%) of those interviewed were college graduates – nearly double the rate among Michigan voters in recent elections. Regardless, a high-profile polling aggregator fed this poll into its average for the state, demonstrating how readily problems from 2016 can repeat.

Since 2016, many pollsters heeded this lesson and added an education adjustment to their work. Additionally, most national pollsters as well as some state pollsters had been making the adjustment for many election cycles and continue to do so. But not all have fixed this issue. For example, a June poll appeared to show Biden with a massive 18-percentage-point lead in Michigan. But a look at the sample shows why: More than two-thirds (69%) of those interviewed were college graduates – nearly double the rate among Michigan voters in recent elections. Regardless, a high-profile polling aggregator fed this poll into its average for the state, demonstrating how readily problems from 2016 can repeat.

One challenge in adjusting for education is identifying the proper benchmark. Using the June poll example, a rate of 69% college graduates is clearly too high. But what is the “right” number? Technically, no one knows, because the goal is to align the survey with the education profile of those who will vote in an election that has not yet happened. While the precise number is unknown, historical data from a large, high-quality federal study ably fills this need. In the month or so following each presidential and midterm election, the U.S. Census Bureau conducts the Current Population Study (CPS) Voting and Registration Supplement. The study does not ask who people voted for, but it does ask whether they voted. With more than 90,000 interviews nationally, more than a third of which are done in-person, the CPS supplement is among the nation’s best measurements of the demographics of voters and nonvoters.

The state-by-state results are freely available to the public, but for many they are difficult to access as they require software and servers that can process large data files. This report provides the CPS data on the education profile of voters in all 50 states and the District of Columbia for the past four presidential elections. State pollsters can use this data to inform their weighting adjustments. Poll observers can use this data to determine whether the share of college graduates in a battleground state poll is reasonable.

There are several critical factors to keep in mind:

Polls should be judged based on their weighted sample. The issue is not whether raw poll samples have too many college graduates. It is almost a given that they do. The issue is whether the pollster has adjusted for the issue – weighting down college graduates proportional to their plausible share of voters in the upcoming election. If a poll’s methodology states that education was included as an adjustment variable, often that is enough to safely assume this issue was addressed. If a poll did not adjust for education, observers curious about quality can ask the pollster what share of the weighted sample were college graduates. Reputable pollsters will recognize why this information would be of interest and provide it. If a pollster is unwilling to provide this information, that is a strong sign that the poll may not be trustworthy.

The expectation should be plausibility, not perfection. The CPS data gives a reality check for the typical proportion of a state’s voters who are college graduates. But the proportion in an upcoming election could always be somewhat higher or lower than in the CPS data. One takeaway from the data compiled here is that large election-to-election changes (for example, more than 8 percentage points) in the college graduate rate are highly unlikely – in other words, implausible. Changes on the order of several percentage points, however, are to be expected. Observers should not expect that a poll exactly mimics prior elections’ education profile; they should only expect that it comes reasonably close. For example, the CPS shows that the share of presidential election voters in Florida who are college graduates has recently been in about the mid-30% range. A 2020 Florida preelection poll should, therefore, have a college graduate rate in its weighted sample of between about 30% and 45%. If the rate is well above 45%, the poll runs the risk of overestimating support for Biden and underestimating support for Trump.1

A plausible education profile is important, but other factors matter too. A poll’s education profile is far from the only factor that observers should consider when evaluating quality. For example, ideally a poll draws its participants from a source that includes nearly everyone in the state (or in the country for national polls). Examples of such sources are registered voter files, telephone random-digit dialing and the U.S. Postal Service residential address database. Other factors that are important to a poll’s trustworthiness include the sponsor, sample size, question wording and adjustments on other variables such as age, sex, race and geography. In other words, a plausible education profile should be on the checklist for trustworthiness in battleground state polls – but there are other items on the list as well.

Ideally, an education adjustment accounts for multiple levels and variation between race groups. For clarity, this analysis focuses on whether college graduates are overrepresented in poll estimates. But for practitioners, additional layers of detail can be important. A college vs. non-college adjustment is good, but a more detailed adjustment aimed at achieving proper representation of more fine-grained levels can be even better. For example, a pollster can use the CPS data to adjust for the share with a high school education or less, the share with some college experience (which typically includes trade schools and two-year college degrees), the share with a four-year college degree, and the share with a graduate degree.

Similarly, in geographies with relatively large shares of Hispanic, Black or Asian American populations, a pollster may further improve accuracy by adjusting the education profile within the largest race and ethnicity groups. For example, Pew Research Center’s national polls are adjusted to ensure that education groups (high school or less, some college, college graduate) are represented properly among Hispanic, Black, White and Asian Americans.

The CPS trend lines generally are fairly stable and slowly increasing. The stability of the state-level CPS trends dispels the notion that a pollster cannot anticipate roughly what the college graduate rate among a state’s voters will be. While other voter demographics (for example, the share who live in rural areas) may shift noticeably, the share who graduated from a four-year college simply do not tend to fluctuate wildly, according to the CPS. Furthermore, to the extent that there is movement, it is somewhat predictable: the college graduate rate has tended to increase by about 2 to 3 percentage points in the last four elections in battleground states. State pollsters could reasonably factor in such a modest increase when adjusting polls this cycle.

While this report focuses on the CPS, there are other useful sources of information that can be used to improve or assess the representativeness of a poll. For example, pollsters sampling from registered voter files can use race, age, sex, political party and other variables on file to adjust their samples. While voter file data on those characteristics can be quite accurate, appended data about voters’ education level tends to be less so. A 2018 Pew Research Center study of five national voter files found that individuals’ education level was either missing or inaccurate 49% of the time, on average, across the files.

Some polls – particularly those releasing estimates for all U.S. adults – do not need weighting targets that are specific to likely or registered voters. An alternative source that works well for such polling is the American Community Survey (ACS). Unlike the CPS, the ACS does not provide data on those who voted in an election. It does, however, provide authoritative data on the shares of all adults with various levels of education at the state level and much lower.

Finally, it is worth reiterating that education is just one of several dimensions that tend to require adjustment is polls. A poll also needs to be representative with respect to geography, age, race, ethnicity, urbanicity, sex and potentially more. Adjustments for political partisanship and urbanicity are increasingly common in polling. As the polling field enters the heat of the 2020 election, it’s imperative that public polls are strong on all the fundamentals, since it may be difficult to predict what new challenge may arise.

Voter’s education distribution has remained relatively stable since in recent presidential elections

Among voters in each state in each general election…

| State | 2004 HS or less | 2004 Some college | 2004 College grad | 2008 HS or less | 2008 Some college | 2008 College grad | 2012 HS or less | 2012 Some college | 2012 College grad | 2016 HS or less | 2016 Some college | 2016 College grad |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| US | 37 | 31 | 32 | 34 | 32 | 34 | 32 | 31 | 37 | 30 | 31 | 40 |

| AL | 42 | 31 | 28 | 44 | 31 | 24 | 39 | 32 | 29 | 35 | 34 | 32 |

| AK | 32 | 38 | 30 | 29 | 38 | 33 | 31 | 38 | 32 | 30 | 34 | 36 |

| AZ | 32 | 36 | 32 | 28 | 35 | 36 | 26 | 38 | 37 | 23 | 36 | 40 |

| AR | 44 | 30 | 26 | 44 | 29 | 26 | 41 | 27 | 32 | 37 | 29 | 34 |

| CA | 28 | 35 | 37 | 27 | 35 | 38 | 25 | 34 | 42 | 25 | 32 | 43 |

| CO | 26 | 30 | 44 | 25 | 31 | 43 | 23 | 34 | 44 | 22 | 30 | 48 |

| CT | 34 | 25 | 41 | 31 | 29 | 40 | 28 | 27 | 45 | 29 | 25 | 46 |

| DE | 39 | 29 | 31 | 41 | 28 | 31 | 35 | 28 | 36 | 36 | 26 | 38 |

| DC | 25 | 19 | 56 | 25 | 21 | 53 | 24 | 16 | 59 | 18 | 16 | 66 |

| FL | 37 | 31 | 32 | 34 | 33 | 33 | 34 | 31 | 35 | 31 | 32 | 36 |

| GA | 36 | 32 | 32 | 35 | 31 | 34 | 36 | 30 | 34 | 33 | 31 | 36 |

| HI | 28 | 35 | 37 | 32 | 30 | 38 | 30 | 31 | 39 | 26 | 31 | 43 |

| ID | 35 | 37 | 28 | 34 | 33 | 33 | 30 | 36 | 35 | 28 | 37 | 35 |

| IL | 35 | 31 | 34 | 34 | 31 | 36 | 30 | 29 | 41 | 28 | 30 | 42 |

| IN | 45 | 29 | 26 | 44 | 29 | 27 | 36 | 30 | 34 | 36 | 29 | 35 |

| IA | 38 | 37 | 26 | 33 | 33 | 34 | 34 | 35 | 32 | 30 | 35 | 35 |

| KS | 33 | 32 | 35 | 28 | 34 | 38 | 28 | 31 | 41 | 25 | 35 | 40 |

| KY | 45 | 30 | 25 | 38 | 36 | 26 | 40 | 34 | 26 | 36 | 33 | 31 |

| LA | 46 | 28 | 26 | 44 | 27 | 29 | 44 | 30 | 26 | 40 | 30 | 31 |

| ME | 44 | 29 | 27 | 40 | 30 | 30 | 36 | 29 | 36 | 34 | 31 | 35 |

| MD | 34 | 28 | 38 | 31 | 28 | 41 | 29 | 27 | 44 | 26 | 28 | 46 |

| MA | 34 | 24 | 42 | 29 | 24 | 46 | 28 | 24 | 48 | 25 | 25 | 50 |

| MI | 41 | 33 | 26 | 36 | 35 | 29 | 35 | 34 | 32 | 30 | 32 | 38 |

| MN | 30 | 36 | 35 | 28 | 36 | 36 | 27 | 35 | 38 | 24 | 34 | 41 |

| MS | 50 | 29 | 21 | 46 | 30 | 24 | 41 | 33 | 26 | 43 | 31 | 26 |

| MO | 40 | 30 | 30 | 39 | 34 | 27 | 35 | 34 | 31 | 36 | 33 | 31 |

| MT | 35 | 37 | 28 | 37 | 32 | 31 | 31 | 36 | 33 | 30 | 34 | 36 |

| NE | 35 | 33 | 32 | 30 | 35 | 36 | 30 | 33 | 37 | 27 | 36 | 38 |

| NV | 38 | 35 | 27 | 35 | 35 | 30 | 35 | 35 | 31 | 30 | 40 | 31 |

| NH | 36 | 27 | 37 | 31 | 31 | 38 | 29 | 30 | 40 | 30 | 28 | 42 |

| NJ | 39 | 25 | 36 | 35 | 25 | 41 | 29 | 27 | 43 | 29 | 24 | 47 |

| NM | 35 | 37 | 28 | 31 | 30 | 40 | 30 | 28 | 42 | 30 | 35 | 36 |

| NY | 38 | 27 | 35 | 34 | 29 | 37 | 32 | 28 | 41 | 28 | 27 | 45 |

| NC | 40 | 29 | 31 | 33 | 33 | 34 | 33 | 34 | 33 | 29 | 33 | 38 |

| ND | 31 | 41 | 28 | 32 | 37 | 31 | 28 | 35 | 37 | 29 | 34 | 36 |

| OH | 43 | 30 | 26 | 41 | 30 | 29 | 42 | 30 | 28 | 37 | 29 | 34 |

| OK | 42 | 29 | 29 | 37 | 32 | 30 | 32 | 32 | 35 | 33 | 28 | 39 |

| OR | 31 | 39 | 30 | 28 | 38 | 34 | 29 | 34 | 37 | 26 | 31 | 43 |

| PA | 42 | 25 | 34 | 41 | 27 | 33 | 37 | 28 | 35 | 35 | 28 | 36 |

| RI | 38 | 25 | 37 | 34 | 29 | 37 | 34 | 28 | 39 | 33 | 29 | 37 |

| SC | 37 | 36 | 26 | 43 | 30 | 27 | 34 | 33 | 33 | 34 | 30 | 35 |

| SD | 39 | 35 | 27 | 35 | 34 | 31 | 33 | 36 | 31 | 28 | 37 | 35 |

| TN | 41 | 31 | 28 | 42 | 28 | 31 | 36 | 29 | 35 | 33 | 29 | 38 |

| TX | 35 | 32 | 33 | 34 | 34 | 32 | 32 | 34 | 34 | 27 | 33 | 41 |

| UT | 30 | 37 | 33 | 26 | 44 | 30 | 24 | 41 | 35 | 20 | 37 | 43 |

| VT | 36 | 26 | 38 | 34 | 27 | 39 | 31 | 26 | 43 | 27 | 27 | 45 |

| VA | 33 | 27 | 40 | 34 | 25 | 41 | 30 | 28 | 42 | 28 | 30 | 42 |

| WA | 28 | 37 | 35 | 24 | 37 | 38 | 26 | 33 | 41 | 24 | 31 | 45 |

| WV | 50 | 26 | 23 | 49 | 30 | 21 | 46 | 26 | 29 | 43 | 27 | 30 |

| WI | 41 | 32 | 27 | 36 | 33 | 32 | 33 | 33 | 34 | 31 | 32 | 37 |

| WY | 37 | 39 | 23 | 36 | 38 | 27 | 37 | 36 | 27 | 28 | 40 | 32 |

Source: Current Population Survey Voting and Registration Supplement 2004-2016