One major challenge researchers may encounter in designing surveys about news consumption: Does the U.S. public understand the range of concepts being measured – concepts that are constantly evolving as news organizations adapt to the ever-changing digital landscape?

This chapter examines this question from several angles, including the public’s overall familiarity with – and use of – new digital forms of news consumption. The results show that most Americans are familiar enough with newer digital devices and services to answer questions about them in a survey, though the adoption of most of these technologies for news consumption remains quite low.

Most U.S. adults also do not report regularly using several top news aggregators, and Americans largely do not know whether some of these aggregators do their own original news reporting. Even when it comes to more traditional news organizations, there is limited knowledge about where news reporting originates. Americans are, at least, largely accurate in self-assessments of their news source literacy: Many express little confidence in their ability to identify original reporting.

The analysis finds that the vast majority of Americans say they have not paid for news in the past year. But, in an increasingly varied news ecosystem, a broad question about paying for news does not appear to capture all the ways that Americans financially support news organizations. Indeed, two follow-up questions asking about more specific ways that people may pay for news find that some Americans – particularly older adults – answer no to the broader question about whether they pay for news but yes to a more specific way of paying for news. And it appears that an even higher share of U.S. adults indirectly supports news organizations financially.

Finally, this chapter explores the different platforms Americans use for news consumption – and how researchers can best measure usage of some of the newer, more specific digital platforms, such as podcasts and internet streaming services.

The findings in this chapter are drawn from an online survey of 2,021 U.S. adults conducted June 2-11, 2020, on Ipsos’ KnowledgePanel (see Methodology for details).

The public is broadly aware of some newer forms of news consumption, but most Americans do not often use them

Among the five new digital platforms mentioned in the survey, streaming services are the most widely known.

Among the five new digital platforms mentioned in the survey, streaming services are the most widely known.

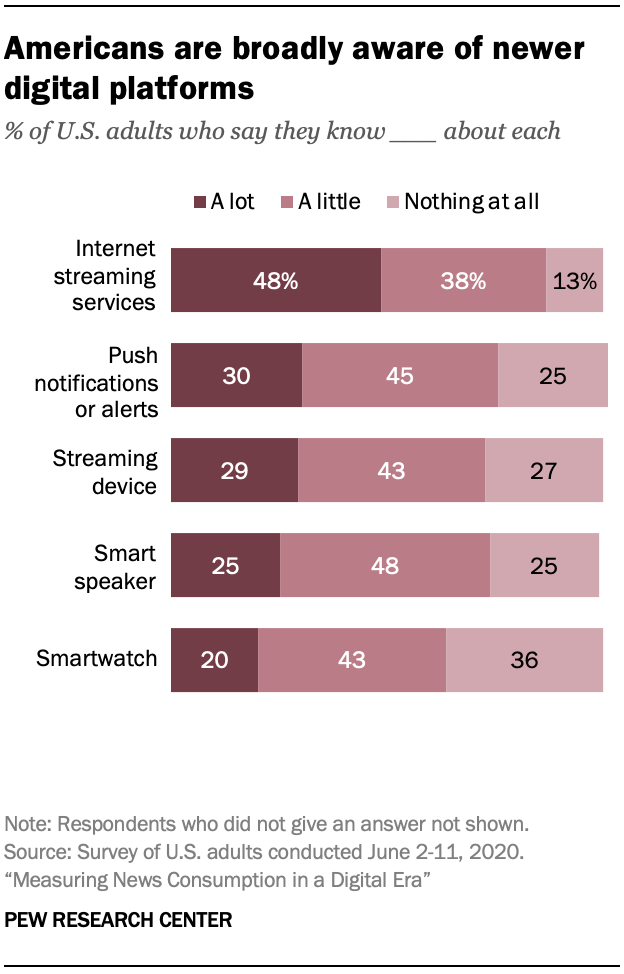

A majority of U.S. adults (86%) are aware of internet streaming services such as Netflix or Hulu. Nearly half (48%) of respondents say they know a lot about these services, while an additional 38% say they know a little about them. Just 13% say they are not familiar with streaming services at all.

Americans also are broadly aware of push notifications and alerts on mobile devices, streaming devices such as Chromecast and smart speakers. About three-quarters of all Americans know at least a little about each of these technologies, though no more than three-in-ten say they know a lot.

Smartwatches are less commonly known, with about a third of Americans (36%) saying they know nothing at all about them and only one-in-five saying they know a lot.

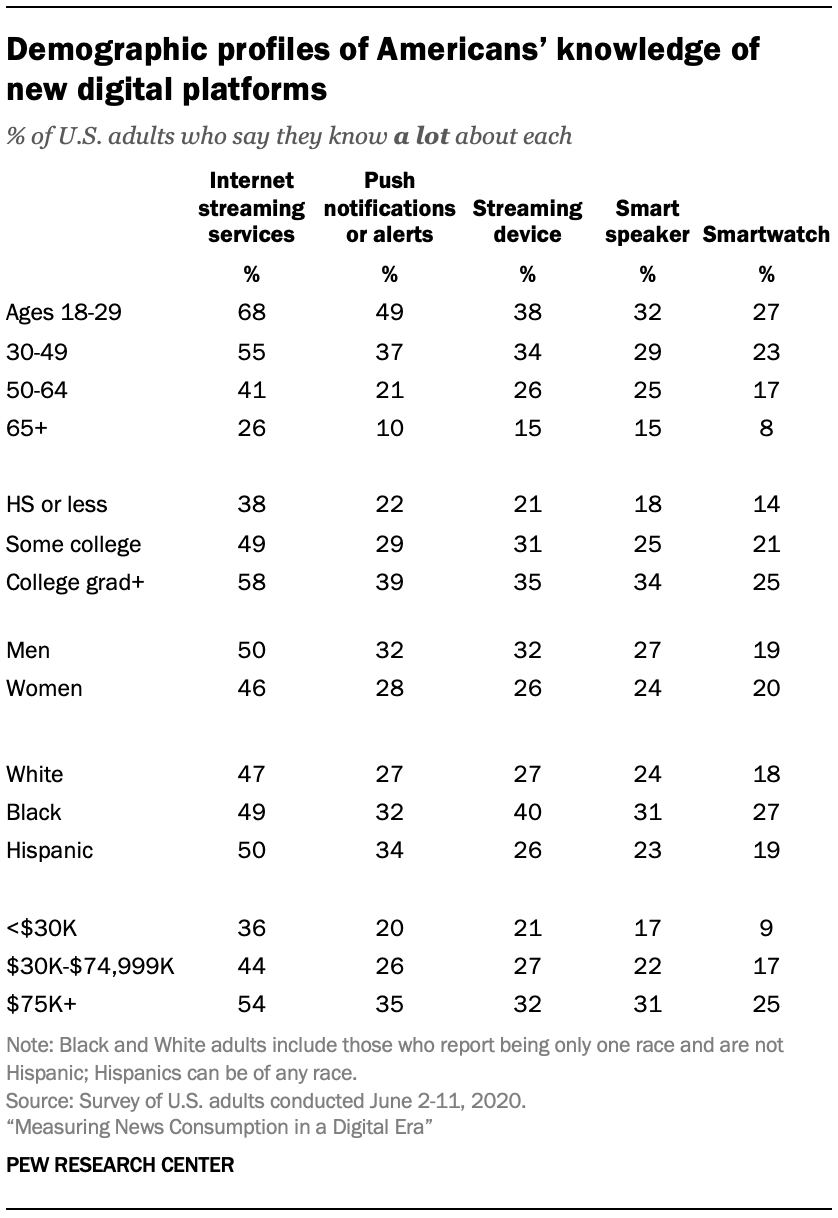

Young adults (ages 18 to 29) are more likely to know a lot about all five types of new digital media, compared with those ages 50 and older. Differences in knowledge are especially stark when younger Americans are compared with those 65 and older: For example, about two-thirds of adults under 30 (68%) say they know a lot about streaming services, while the same is true of only 26% of those ages 65 and older – a gap of 42 percentage points.

Young adults (ages 18 to 29) are more likely to know a lot about all five types of new digital media, compared with those ages 50 and older. Differences in knowledge are especially stark when younger Americans are compared with those 65 and older: For example, about two-thirds of adults under 30 (68%) say they know a lot about streaming services, while the same is true of only 26% of those ages 65 and older – a gap of 42 percentage points.

Higher levels of education (and income) also are associated with greater knowledge of new digital platforms. Those with a bachelor’s degree or higher are more likely than those with lower education levels to say they know a lot about each of these new digital platforms.

Familiarity with some of these newer digital platforms is higher among Black Americans than White or Hispanic Americans. For instance, Black Americans (40%) are more likely than White (27%) or Hispanic (26%) Americans to say they know a lot about streaming devices, such as Roku, Chromecast or Fire Stick.

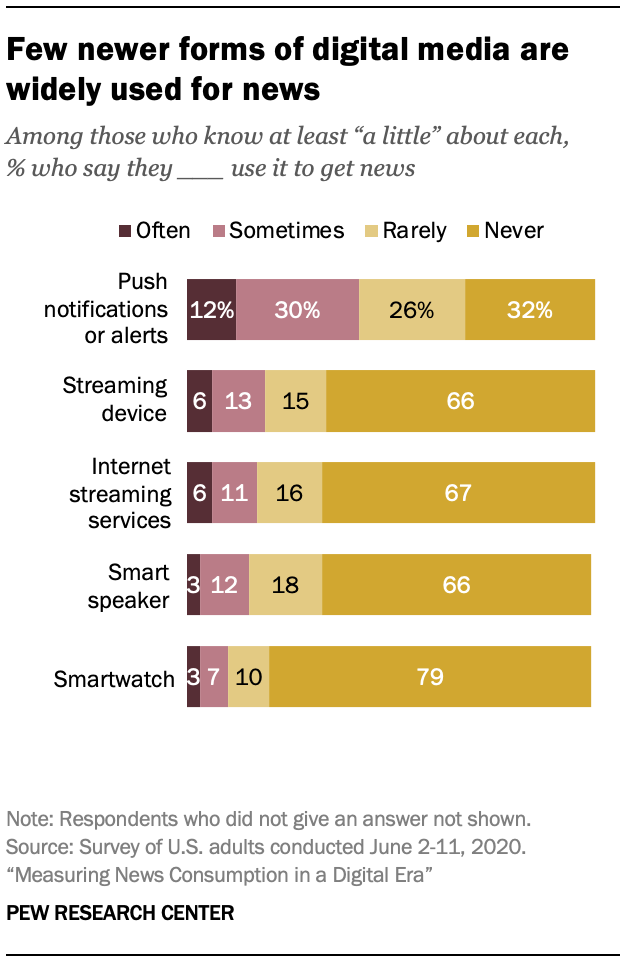

Among those with at least a little knowledge of these devices or services, only small portions report using them to get news – with the exception of push notifications.

Among those with at least a little knowledge of these devices or services, only small portions report using them to get news – with the exception of push notifications.

About four-in-ten Americans who are aware of push notifications say they “often” (12%) or “sometimes” (30%) use them for news. An additional 26% say they “rarely” use push notifications for news, while 32% of individuals with knowledge of push notifications never use them to get news.

By contrast, around two-thirds of those who are familiar with internet streaming services (67%), streaming devices (66%) and smart speakers (66%) never use them to get news. And an even greater share of Americans with knowledge about smartwatches (79%) never use them to get news.

These results are consistent with findings from the cognitive interviews that streaming devices, streaming services and smartwatches are not popular for accessing news, despite most respondents being familiar with these new platforms.2

Overall, the results show that most people – at least in the U.S. – are familiar enough with newer digital devices and services to answer questions about them in a survey, though adoption for news consumption is currently quite low.

News aggregators are used at varying rates

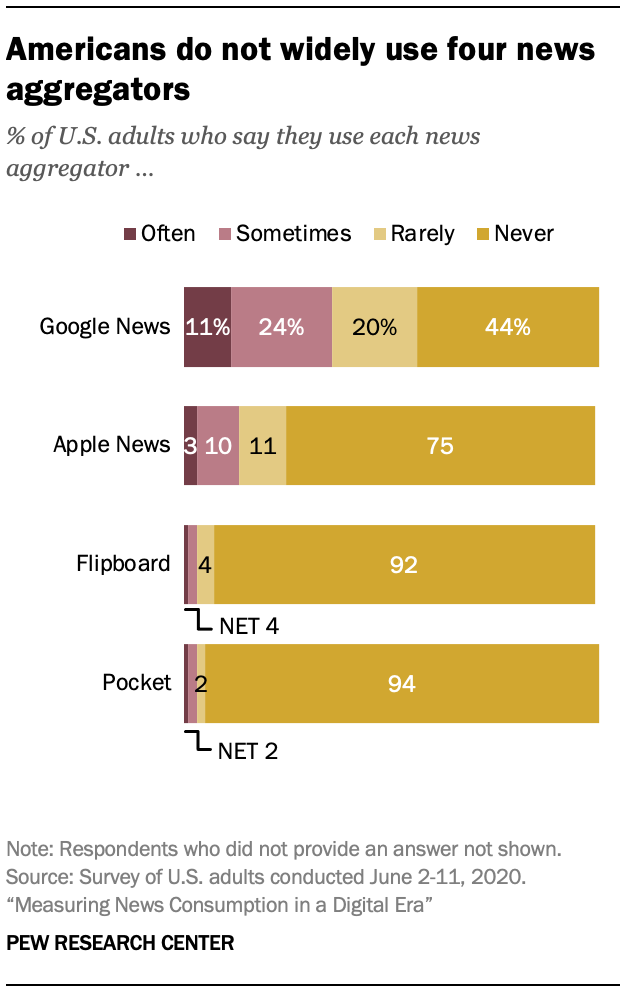

News aggregators – websites, apps and other services that compile news from a variety of different original sources – are another form of news consumption unique to online spaces. The survey asked respondents how often they use four of the most widely used news aggregators (based on fourth-quarter 2019 traffic measured by Comscore): Google News, Apple News, Flipboard and Pocket.

News aggregators – websites, apps and other services that compile news from a variety of different original sources – are another form of news consumption unique to online spaces. The survey asked respondents how often they use four of the most widely used news aggregators (based on fourth-quarter 2019 traffic measured by Comscore): Google News, Apple News, Flipboard and Pocket.

Google News is the most widely used: Roughly one-in-ten U.S. adults (11%) report using it often, and about a quarter (24%) say they use it sometimes. Apple News is less widely used, with 3% saying they get news there often and 10% doing so sometimes. And fewer than 5% of Americans use either Flipboard or Pocket at least sometimes, while roughly nine-in-ten never use these two aggregators.

Google News is more likely to be used often or sometimes by Black adults (44%) and Hispanic adults (45%) than White adults (29%). Democrats (and Democratic-leaning independents) are more likely than Republicans (and independents who lean Republican) to use Google News or Apple News at least sometimes.

Some news aggregators, then, seem to play a larger role in digital news consumption than others, suggesting that including some of the most prominent ones could be a worthwhile addition when seeking to gather a full picture of news intake. However, additional questions remain about how people distinguish such news aggregators and organizations who do original reporting – questions explored next in this study.

Little public confidence in identifying original reporting – and little success

Amid the variety of new digital platforms that people can use to access news, confusion emerges when people are asked to distinguish news sources that do original reporting from those that do not.

Just over half of Americans (55%) are at least fairly confident they can differentiate between organizations that do original news reporting versus those that do not, including 46% who are pretty confident but only 9% who feel very confident. The remainder are either not too (35%) or not at all (8%) confident they can identify organizations that do original reporting.

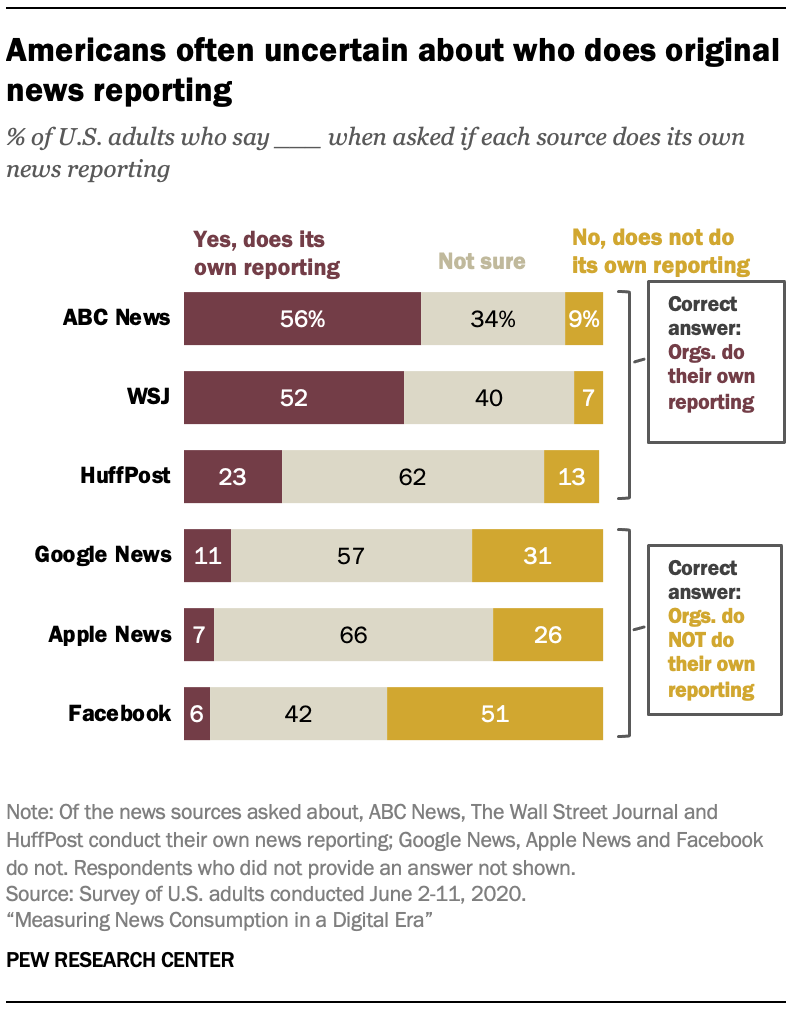

This general uncertainty is also evident in respondents’ answers to fact-based questions in which respondents were shown six different sources they could get news from, and then asked: “Do you believe that each of the following does its own news reporting?”3 The results show that the ability to correctly identify whether news sources do their own reporting is limited – and also varies widely by source.

This general uncertainty is also evident in respondents’ answers to fact-based questions in which respondents were shown six different sources they could get news from, and then asked: “Do you believe that each of the following does its own news reporting?”3 The results show that the ability to correctly identify whether news sources do their own reporting is limited – and also varies widely by source.

Around half or more correctly identify that ABC News (56%) and The Wall Street Journal (52%) do their own original reporting, while 51% know that Facebook does not do its own reporting.

But respondents are much less likely to give correct answers about HuffPost (23% correctly say it does its own reporting), Google News (31% correctly say it does not do original reporting) and Apple News (26% correctly say it does not do its own reporting).4 It is not that more Americans answer these questions incorrectly; rather, more than half say they are unsure whether each of these sources does its own original reporting.

In the case of HuffPost, this may reflect a lack of familiarity with the outlet among many Americans: A separate study, conducted in November 2019, found that, while 93% of Americans have heard of ABC News and 79% have heard of The Wall Street Journal, fewer (63%) have heard of HuffPost. And in that survey, while 70% had heard of Google News, only 35% had heard of Apple News.

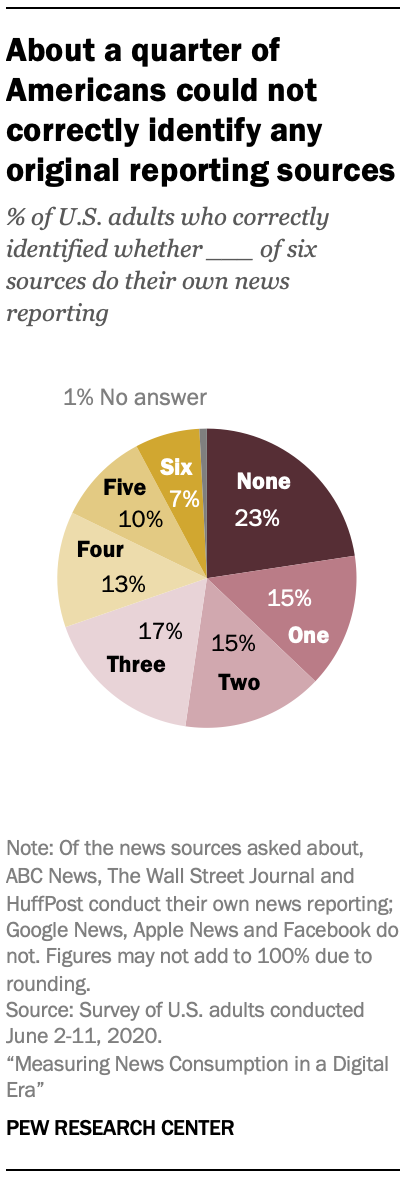

All in all, nearly a quarter of Americans (23%) could not correctly identify whether any of the six sources do original reporting, and an additional three-in-ten got only one (15%) or two (15%) questions right. The remaining 47% were able to answer three or more questions correctly, but only 7% correctly classified all six sources based on whether they do their own reporting.

All in all, nearly a quarter of Americans (23%) could not correctly identify whether any of the six sources do original reporting, and an additional three-in-ten got only one (15%) or two (15%) questions right. The remaining 47% were able to answer three or more questions correctly, but only 7% correctly classified all six sources based on whether they do their own reporting.

Although Americans generally do not have a strong sense of confidence in their ability to identify sources that do original reporting, greater self-assessed confidence does line up with higher levels of actual knowledge. Among those who correctly answered all six questions, 81% initially said they are confident (including 20% who are very confident) in their ability to distinguish between sources that do original news reporting and those that do not. Conversely, only 33% of those who could not correctly identify any sources said they are confident in their ability to do so (including just 4% who are very confident).

Previous Center research has found that Republicans are generally less likely to think the news media are professional or report news accurately. As such, it is possible that some Republicans treated these not as knowledge questions but as an opportunity to express that news organizations do not engage in professional practices. Indeed, Democrats (and Democratic-leaning independents) are generally more likely than Republicans (and Republican-leaning independents) to correctly say that ABC News, The Wall Street Journal and HuffPost do their own reporting – including about twice as likely to say HuffPost does original reporting (31% vs. 15%). Still, roughly half of Republicans correctly answered that ABC News (47%) and The Wall Street Journal (48%) do their own reporting.

Full scope of financial support for news organizations not captured with simple ‘paying for news’ question

Decades ago, most Americans could easily tell if they financially supported a news organization, since the only available mechanisms were to subscribe to or individually purchase print publications or donate to a public broadcaster. The other news options of radio and commercial broadcast TV news were free to access, minus the initial cost of the physical device.

Decades ago, most Americans could easily tell if they financially supported a news organization, since the only available mechanisms were to subscribe to or individually purchase print publications or donate to a public broadcaster. The other news options of radio and commercial broadcast TV news were free to access, minus the initial cost of the physical device.

The advent of cable and then the web, however, brought a wide variety of ways to directly and indirectly support news organizations financially. This includes both direct forms of support – such as becoming a member of an online news site or using a subscription service like Substack – and indirect forms of support, including cable or satellite subscriptions that go toward paying license fees for network affiliates and cable news channels. Americans also can pay to access news in a way that does not directly benefit any news organizations, such as by paying for internet access and using that connection to access free news sites or social media.

What it means to “pay for news,” then, is another concept impacted by technological and digital advancements. As such, the study examines what people tend to think of – and not think of – when asked about paying for news. The results indicate the importance of using specific language about the possible types of financial support that researchers are interested in measuring.

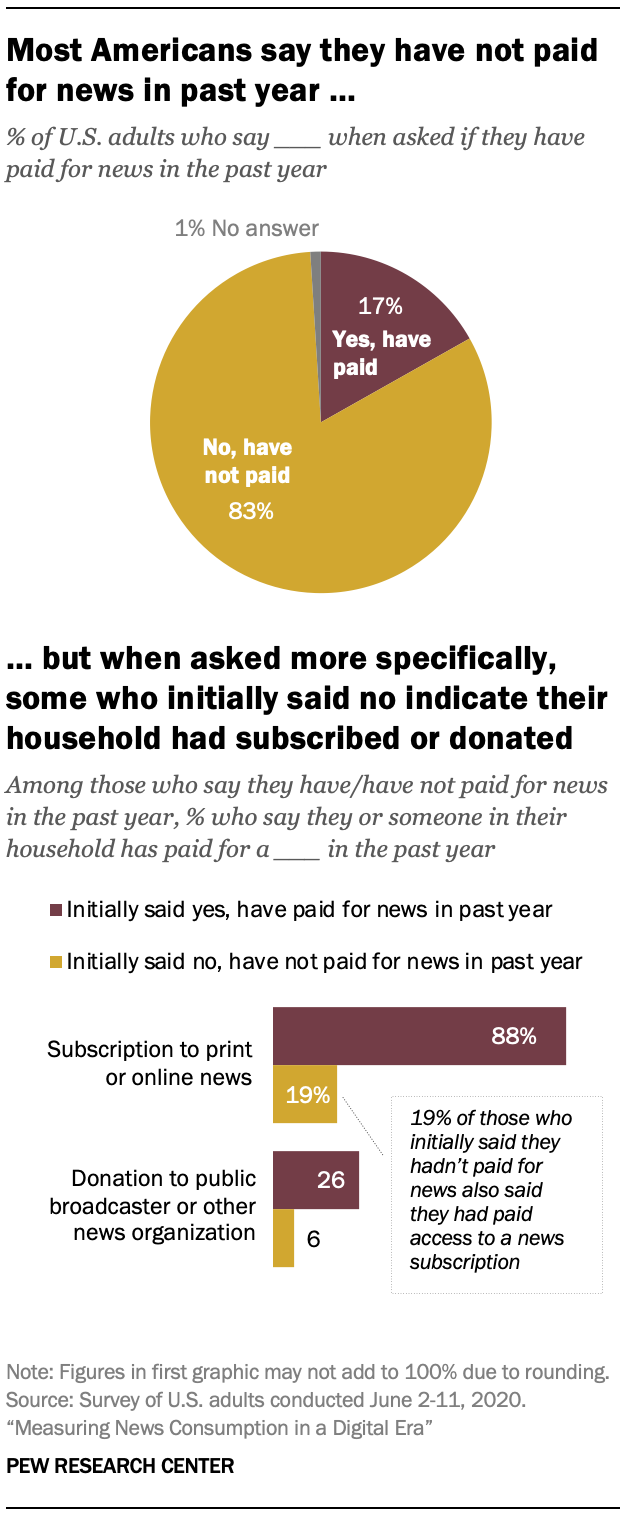

When asked simply whether they have “paid for news in the past year,” only 17% of Americans say they have done so. The overwhelming majority (83%) say they have not paid for news.

Separate, more specific questions, however, reveal that this seemingly straightforward question does not capture the full range of how Americans pay for news. Among those who say they haven’t paid for news in the past year, nearly one-in-five (19%) also say they or someone in their household has paid for a subscription to a newspaper, magazine or news website in the past year. Also, within the group who initially denied having paid for news, 6% say they or a household member have donated to a public broadcaster or other news organization during the same time period.

The more specific questions add in the option of someone else in their household being the one who pays for news. That specificity, however, does not seem to be the primary factor in the situations where there is a disconnect between respondents’ answers. That is because those in multiperson households are about as likely as those in a single-person household to have a mismatch between the initial question and the donation and print or online subscription follow-ups. In other words, both groups are about as likely to have the follow-ups “catch” additional ways of paying for news directly.

For example, among those who say they did not pay for news in the past year, 15% of those in a single-person household also say they (or someone in their household) paid for a subscription to print or online news in the past year, while 20% of those who live with at least one other person say this. When it comes to donations to a news organization, the figures are exactly the same (6% for both those in single-person and multiperson households).

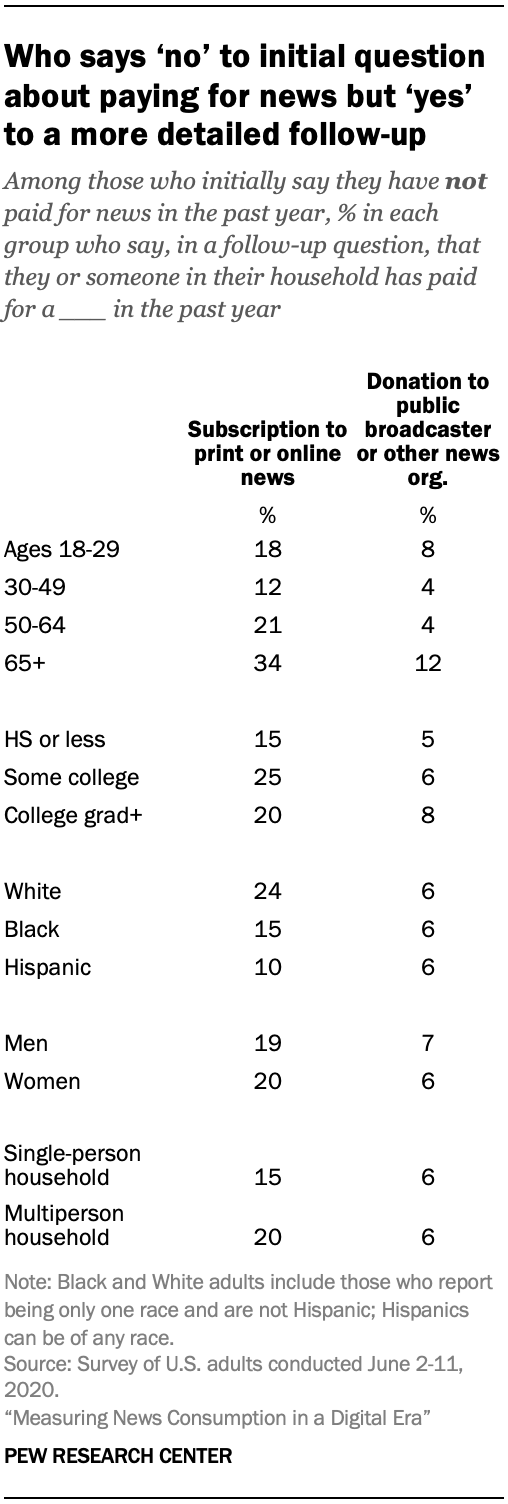

Some demographic differences emerge in the likelihood of missing certain types of payment in the simple approach.

Some demographic differences emerge in the likelihood of missing certain types of payment in the simple approach.

Those ages 65 and older are more likely than their younger counterparts to provide differing answers on the general question about paying for news and the more specific question about paying for a subscription. And White adults are also more likely than Black or Hispanic adults to do so.

For donations to public broadcasters or other news organizations, again, those ages 65 and up are more likely than adults between 30 and 64 to say they provided a donation after initially saying they had not recently paid for news.

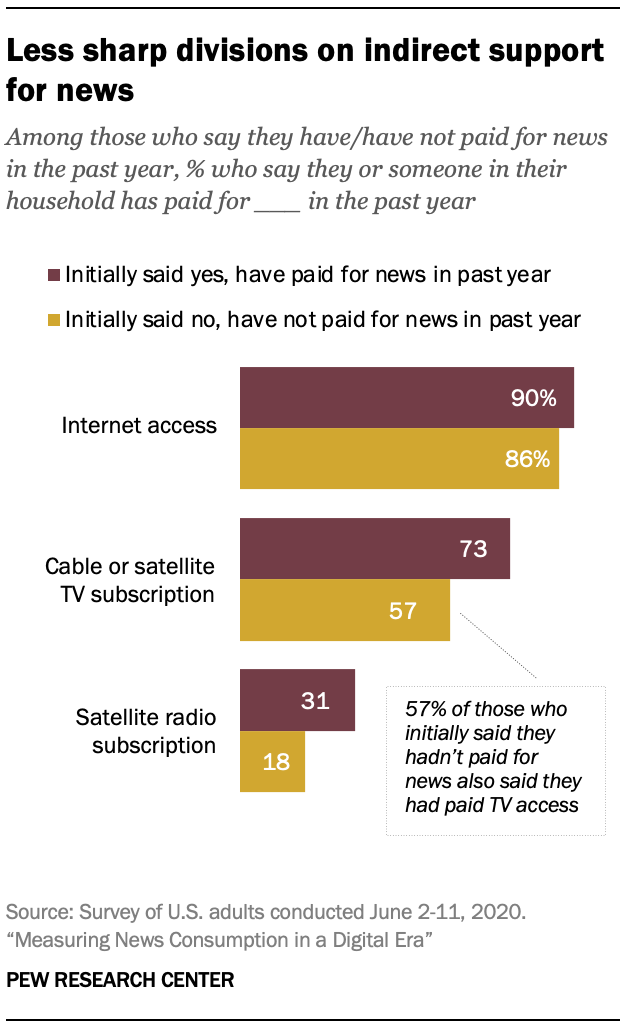

This analysis also reveals that indirect payment is also not entirely captured in a general “pay for news” question.

This analysis also reveals that indirect payment is also not entirely captured in a general “pay for news” question.

Among those who say they don’t pay for news, over half (57%) do pay for a cable or satellite TV subscription, and 18% pay for a satellite radio subscription. This may not be part of a researcher’s definition of “paying for news,” but since some revenue does flow from these subscriptions to news organizations (including cable TV channels and local TV channels), these payments do result in increased financial resources for some news organizations.

On one final item where no money flows to news organizations – paying for internet access – there is no substantial difference between those who initially say they had and had not paid for news.

Understanding how use of new digital platforms overlaps with use of analog and digital platforms for news consumption

In the digital age, it is possible to obtain news through various platforms, services and devices, with news content originally published through one avenue easily being shared elsewhere. For example, a news excerpt that is originally broadcast on national TV could also be available to watch online through a computer or mobile device. The same is true for radio broadcasts that can be accessed through podcasts and, more recently, smart speakers.

Analyzing the relationships between how people use analog (e.g., TV, radio or print publications) and digital media together can inform the best ways to measure news consumption overall. In other words, does a broad platform measure (e.g., asking about TV, radio, print and digital devices) already capture nearly all news consumption in the U.S., or is it also necessary to include specific, newer digital forms of news consumption – such as streaming devices or smart speakers – in future survey questions in order to get a full picture of Americans’ news habits?

Results show that streaming seems to be well captured by a broad platform question, though it is unclear if it overlaps more strongly with TV or digital devices. This is also largely the case for podcasting in terms of its overlap with radio and with digital devices.

Do survey respondents associate streaming, podcasts with broader platforms?

In this digital era, it is reasonable to question to what extent it is necessary to ask about newer forms of news consumption in surveys to capture the full scope of Americans’ news habits. Since the old analog trio of TV, radio and print no longer encompasses the entire universe of news consumption, and since, in cognitive interviews, respondents did not consider all forms of digital news consumption when asked a broad question about their use of smartphones or computers for news, do questions about these new platforms add anything to the overall news consumption picture? Or are they edge cases – interesting in and of themselves but of relatively minor importance to a holistic picture of Americans’ news habits?

In this digital era, it is reasonable to question to what extent it is necessary to ask about newer forms of news consumption in surveys to capture the full scope of Americans’ news habits. Since the old analog trio of TV, radio and print no longer encompasses the entire universe of news consumption, and since, in cognitive interviews, respondents did not consider all forms of digital news consumption when asked a broad question about their use of smartphones or computers for news, do questions about these new platforms add anything to the overall news consumption picture? Or are they edge cases – interesting in and of themselves but of relatively minor importance to a holistic picture of Americans’ news habits?

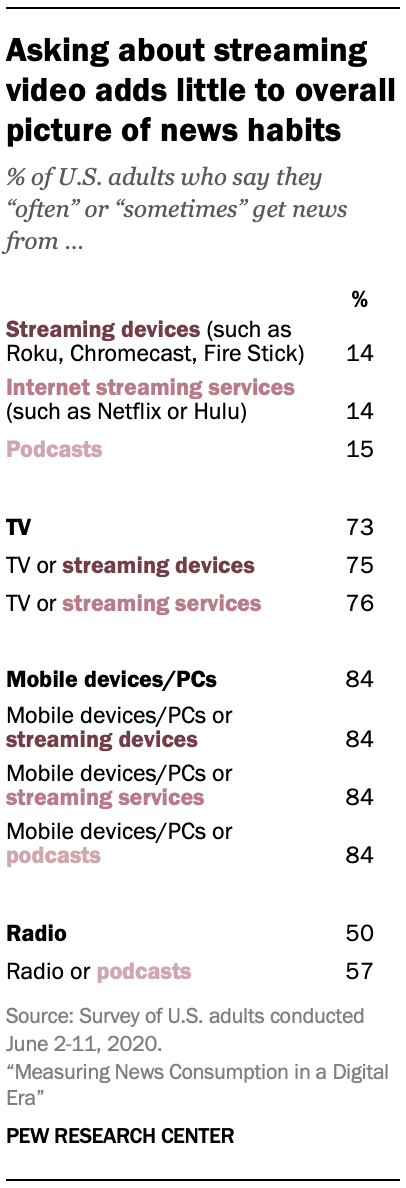

Among all U.S. adults, only small portions of respondents say they at least sometimes get news from streaming devices such as a Roku, Chromecast or Fire Stick (14%); internet streaming services like Netflix or Hulu (14%); or podcasts (15%). By contrast, large majorities say they get news from TV (73%) or from mobile devices or PCs (84%). There also seems to be a lot of overlap: The vast majority of those who get news from streaming devices or services also say they get news from TV or digital devices. As a result, including streaming devices or services in the totals – e.g., the portion of respondents who get news either from TV or from streaming devices – is nearly identical to the portion who get news from TV or mobile devices alone, suggesting that it is probably not necessary to ask specifically about getting news from streaming services or devices.

Asking about news consumption via podcasts specifically, however, does seem to bring something new to the table – at least, if podcasts are considered to be part of radio. There is a difference of 7 percentage points between the portion of respondents who at least sometimes get news from either radio or podcasts compared with radio alone (57% vs. 50%). However, the portions are identical when it comes to digital devices, and, as the data below show, podcast usage overlaps far more strongly with the use of digital devices than with radio.

Overlap of streaming and podcast use with analog or digital platforms

To understand whether these new platforms would be more strongly associated with analog or digital platforms, researchers looked at the overlap between use of streaming for news consumption and use of either TV or digital devices for this purpose. A separate analysis examined the crossover between news consumption via podcasts and either radio or digital devices.

To understand whether these new platforms would be more strongly associated with analog or digital platforms, researchers looked at the overlap between use of streaming for news consumption and use of either TV or digital devices for this purpose. A separate analysis examined the crossover between news consumption via podcasts and either radio or digital devices.

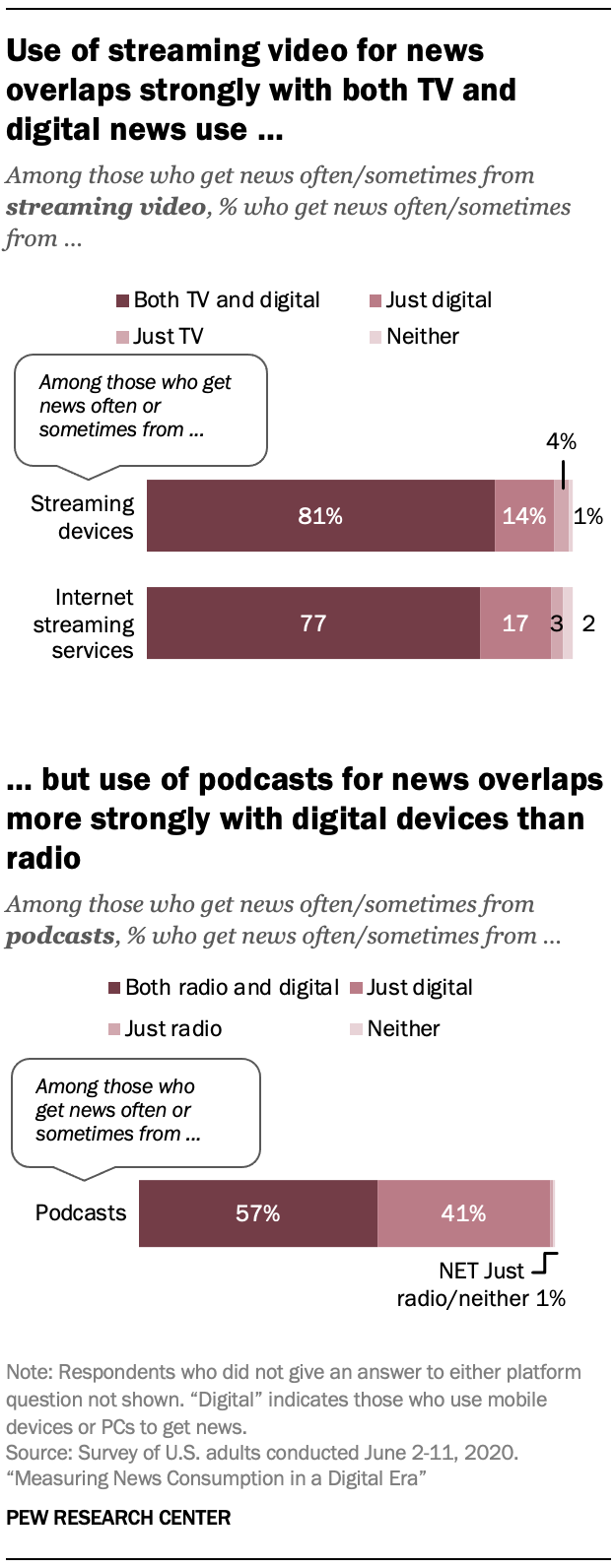

Those who say they often or sometimes use streaming devices and internet streaming services for news were divided into four categories: those who also say they get news (at least sometimes) from both TV and digital devices; those who also get news from TV but not digital devices; those who get news from digital devices but not TV; and finally, those who say they don’t get news from either TV or digital devices.

Use of streaming devices for news overlaps strongly with both TV and digital devices. About eight-in-ten of those who say they at least sometimes get news from streaming devices (81%) also get news from both TV and digital devices. The same pattern is apparent for streaming services: 77% of those who get news from streaming services also say they get news from both TV and digital at least sometimes. In both cases, larger shares say they get news only from digital devices rather than only from TV, but these portions are small and reflect higher overall use of digital devices than TV for news consumption. In both cases, very few (1%-2%) in either group say they do not get news from TV or digital devices.

A different pattern is apparent for use of podcasts, which overlaps far more strongly with use of digital devices than radio. While a slim majority of those who say they at least sometimes get news from podcasts say they get news from both digital devices and radio (57%), about four-in-ten say they get news only from digital devices – not radio (41%). Fewer than 1% say they get news only from radio but not from digital devices. Again, virtually none (less than 1%) say they get news from neither of these broader platforms.

These results may in part reflect the sequencing of these questions: The question about use of podcasts for news was included as a follow-up question for those who said they ever get news from digital devices. Still, the analysis suggests that including podcasts as a separate item in survey questions about news consumption may add clarity to the overall picture of Americans’ news consumption habits, while items about streaming video devices or services can be used on an as-needed basis.

At the same time, results from the cognitive interviews suggest that, even though people are generally familiar with streaming devices, they do not commonly think of streaming devices when considering ways to access news. This is in line with results from the survey, which finds relatively little use of streaming devices for news – despite widespread familiarity with the devices. It seems that, among those who say they don’t use them for news, newer platforms like streaming devices are not considered news sources but, rather, digital or technological gadgets that make it possible to get news and other information if one wanted to. When asked if they associate streaming devices with other news platforms, one participant (man, age 35) said, “No, I wasn’t thinking about streaming devices at all. I think things like Roku are in a league of their own.”

As a follow-up probe in the cognitive interviews, those who said they use streaming devices to get news were asked whether they saw it as more akin to getting news from a television or from a digital device. A few participants said that they see them as more similar to getting news online or on digital devices, while others said they considered news accessed via a streaming device to be TV.

Still others said they see streaming devices as being somewhere in between TVs and digital devices, including one man (63) who called them “kind of a hybrid,” and another man (68) who said such devices “turn your TV into a terminal so you can get internet-provided content.”

In addition, six participants felt that watching news through streaming services like Netflix was more like watching news on TV, and two felt it was more like getting news online. Cognitive interview participants who said streaming services were like TV mostly focused on the device they use for streaming when making that determination – those who watched Netflix on their television were more likely to see it as watching TV.