Introduction

Since the start of the 21st century, the internet has evolved from a novelty accessed by half of the American population to a resource now used by nearly 90% and a primary way for the public to keep up with the news, events and issues of the day. This is true as well when it comes to our nation’s presidential elections: Roughly two-thirds of Americans (65%) report learning about the election on the web. Across the past five presidential election cycles, Pew Research Center has studied the evolution of digital news options from web portals and news sites to the websites of the presidential campaigns themselves. Below are highlights from each of those reports. While the data from year to year can’t always be directly compared due to the rapidly shifting state of technology (and resulting changes in the study designs themselves), the snapshot findings from each year speak to both dramatic change and areas that even today are still developing.

2000

Al Gore (D) vs. George W. Bush (R)

Al Gore (D) vs. George W. Bush (R)

The Center conducted its first study of online election-related news and information during the primary season of 2000. That year, nearly a quarter of Americans got at least some of their campaign news through the internet, but only 6% named it as their primary source for campaign news.

While many of the candidates did have campaign websites, these varied in navigability, scope and depth, and the information provided there was not consistently updated. Instead, online campaign news mainly flowed through a mix of traditional news outlets, like The New York Times and MSNBC and web portals like Netscape and Yahoo, whose main feature was aggregated news from several news organizations. A study of six selected dates of primary coverage on the political front pages of 12 of these sites (five web portals, six news websites tied to legacy outlets and one digital-native news site) found:

The use of links to additional information was still very much in development. Unlike today’s online news sites, where embedded links are a regular feature, three of the sites offered no links to external news sites, while another five had just one to three such links across the entire time period studied. Links to other kinds of external site such as Vote-Smart.org, a site that provided aggregated information about candidates, were even less common. Internal links to background information or the voting calendar were somewhat more common, though even here there were a couple of sites where a user could not find any such information. Less than half the sites offered any links to information on the policy stances of the candidates.

Opportunities for the public to engage with the site, such as by taking a survey or voting on the candidates, were rare, but some sites made it a priority. Three of the sites studied did not offer any opportunity on their front pages for readers to “take part.” Another three offered only one to two interactive elements. Still, some of the sites, such as The Washington Post and MSNBC, stood out by offering multiple interactive elements, everything from an online game to online discussions with reporters to “candidate matchmaker” which allowed users to compare their views on issues with those of the candidates.

Sites were split in whether they offered unfiltered audio or video. Four of the 12 sites gave no access to raw video such as from a candidate debate, while another four regularly offered seven or more such videos.

2004

John Kerry (D) vs. George W. Bush (R)

John Kerry (D) vs. George W. Bush (R)

2004 was the first presidential election year in which digital tools played a major role. However, while more digital-native news providers had emerged and some new features were introduced, there was also backward movement in certain areas.

The study of seven days of election coverage during the primary season examined the political front pages of 10 popular news web sites (three digital natives – Salon, AOL and Yahoo – and eight legacy news outlets) and found that:

Compared with four years earlier, news sites provided citizens with more ways to gather additional information about the candidates or election news. Seven of the 10 sites contained links on their front pages for users to learn about candidates’ policy positions, more than four years earlier. Seven also contained biographical background information, and eight offered basic voter information about the primary process.

But, interactivity remained scarce. Four of the 10 sites studied had no interactive links on their front pages, offering even fewer opportunities than in 2000 for users to “take part” in the news. Instead, sites were opting to customize static information such as a clickable map with details about a state’s primaries.

Websites were still hesitant to send users outside their own walled gardens. Seven of the 10 sites studied had no links to external, non-news sites, a downtick from four years earlier that may have been attributed to the demise of political news sites such as Voter.com. Six of the 10 contained no links to external news organizations, including some that four years ago were more collaborative.

The web was still heavily text-oriented, even at television-based sites. Five of the 10 sites offered no audio and visual links to multimedia content, including CNN. The ones that did often used more limited technology than in 2000.

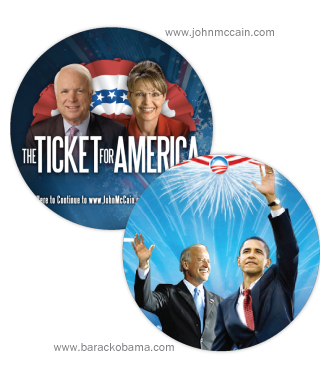

2008

Barack Obama (D) vs. John McCain (R)

Barack Obama (D) vs. John McCain (R)

By the 2008 election season, the presidential candidates had begun in earnest to use digital tools to communicate directly with the public. All 19 of the candidates for president had websites; blogs and social media were the hot new formats and opened up a wide array of opportunities for voters to connect and participate.

With that in mind, our analysis of the 2008 election moved from analyzing news media sites to analyzing the candidates’ own websites as news and information resources. The study of 19 presidential campaign websites over a period of a month from May to June 2007 found that:

Blogs took the 2008 election by storm. Fully 15 of the 19 candidates had official campaign blogs on their sites, and two of the four who did not have blogs offered similar participatory alternatives: user-based forums or links to outside blogs.

Social networking sites also entered the fray as a way to connect. Myspace, Facebook, YouTube, Meetup and Flickr served as connection points with voters, and at the time Myspace ruled the pack: 16 of the 19 candidates linked on their campaign websites to an official Myspace account. The number of followers (referred to as “friends” on that site) was far short of the numbers we see today. Obama was the only candidate to exceed 100,000; most had fewer than 40,000.

At the same time, though, candidate websites were not bypassing mainstream press. All but one of the sites included mainstream news articles in their regularly updated content.

Citizens had ample ways to join in. Information for initiating grassroots activities was common: 12 sites helped supporters organize community events and eight provided supporters with tools for hosting fundraisers. And, in addition to their own blogs, more than a third of the sites (seven of 19) encouraged supporters to start their own blogs connected to the campaign.

Of the various voter tools studied, the least common one offered was information on registering to vote. Only four of the 19 candidates had this information on their sites. On the other hand, biographical information was featured prominently on all 19 candidate sites, as were issue pages.

Video became a bigger part of the information stream. Fully 17 of the 19 candidates featured video components on their front pages, indicating an emphasis on audiovisual content that was not evident in studies of previous elections. This came as YouTube, which debuted in 2005, became a striking new venue for candidates to post longer videos than in conventional political advertising.

2012

Barack Obama (D) vs. Mitt Romney (R)

Barack Obama (D) vs. Mitt Romney (R)

By 2012, the candidates’ campaign communications were just as much about bypassing the filter of traditional media as about mastering changing technologies to get their message to the voters.

An examination of content published on the social media platforms and websites of presidential candidates Barack Obama and Mitt Romney over two weeks in June 2012 found:

A reduced role for traditional news media: The Obama website no longer had a “news” section with recent media reports. Instead, the only news came directly from the campaign itself. Romney’s website still contained a page dedicated to news media accounts which either spoke positively of Romney or negatively of Obama.

Large gaps emerged between the campaign’s technological advancement and level of digital activity. Overall, the Obama campaign’s activity far outpaced Romney’s. Obama, for example, had public accounts on nine separate social platforms in June, versus five for the Romney campaign, and posted nearly four times as much content as the Romney campaign. In general, the Romney campaign put more emphasis on Facebook and blogs, while the Obama campaign was most active on Twitter.

Large gaps emerged between the campaign’s technological advancement and level of digital activity. Overall, the Obama campaign’s activity far outpaced Romney’s. Obama, for example, had public accounts on nine separate social platforms in June, versus five for the Romney campaign, and posted nearly four times as much content as the Romney campaign. In general, the Romney campaign put more emphasis on Facebook and blogs, while the Obama campaign was most active on Twitter.

People were offered many ways to tailor campaign news to their interests – especially on Obama’s website – and were strongly encouraged to take action on- or offline. Obama’s campaign allowed users to customize their digital interactions by offering 18 different constituency groups (such as blacks, women or young Americans). And about half of each candidate’s posts – whether in their blogs or social media account – included a request for some kind of voter follow-up activity. Every blog post from Obama’s campaign included some call to action, whether to donate money, sign up to be part of a team or share something on social media, as did 81% of Romney’s homepage content.

But the campaigns rarely engaged directly with the public. Only 3% of Obama’s total tweets were retweets from the public, while Romney’s single retweet was one of his son’s tweets. Obama did give high priority to citizen voices on his campaign news blog, where 42% of the posts were produced by members of the public. Only two Romney blog posts were from members of the public.

Both candidates used social media and their websites to discuss campaign issues. Half of Obama’s digital posts and 40% of Romney’s were about domestic issues. The economy was the most prominent subject: Nearly a quarter (24%) of Romney’s posts and 19% of Obama’s focused on the economy.

Both candidates often included links in their digital posts, but the campaign website was still the hub of digital activity. About half of all posts studied – whether in blogs or social media – contained some kind of link (44% for Romney and 51% for Obama). The vast majority took users to another part of the campaign’s controlled communications (71% of Obama links, 76% of Romney links), rather than to an external, independent or verifying source. Only 5% of either candidate’s digital posts included links to a traditional news site.

Both candidates often included links in their digital posts, but the campaign website was still the hub of digital activity. About half of all posts studied – whether in blogs or social media – contained some kind of link (44% for Romney and 51% for Obama). The vast majority took users to another part of the campaign’s controlled communications (71% of Obama links, 76% of Romney links), rather than to an external, independent or verifying source. Only 5% of either candidate’s digital posts included links to a traditional news site.

2016

Hillary Clinton (D) vs. Donald Trump (R)

Sixteen years after the Center’s first study of digital communication in a presidential campaign, social media is central to candidates’ outreach to the public, changing the role and nature of the campaign website. While the candidate website still serves as a hub for information and organization, it has become leaner and less interactive compared with four years ago. Campaigns are active on social media though even here the message remains a very controlled one, leaving fewer ways overall for most voters to engage and take part.

Sixteen years after the Center’s first study of digital communication in a presidential campaign, social media is central to candidates’ outreach to the public, changing the role and nature of the campaign website. While the candidate website still serves as a hub for information and organization, it has become leaner and less interactive compared with four years ago. Campaigns are active on social media though even here the message remains a very controlled one, leaving fewer ways overall for most voters to engage and take part.

Two separate studies examining the campaign websites of Hillary Clinton, Bernie Sanders and Donald Trump from May 1-June 15, 2016, and on Facebook and Twitter from May 11-May 31, 2016, find that:

Clinton’s campaign has almost entirely bypassed the news media while Trump draws heavily on news articles. Clinton’s website offers two main sections for campaign news updates, both of which mimic the look and feel of a digital news publisher, but oriented around original content produced in-house. Trump, on the other hand, mostly posts stories from outside news media on his website. This pattern is also evident on social media, where 78% of Trump’s links in Facebook posts send readers to news media stories while 80% of Clinton’s direct followers to campaign pages. On Twitter, a similar tendency emerges in what each links to. Sanders, for the most part, falls in between the two.

On websites, citizen content is minimized or excluded altogether; in social media, Trump stands out for highlighting posts by members of the public. Unlike previous cycles, none of the sites offers the user the option to create a personal fundraising page, nor do their news verticals have comment sections. And only Sanders affords supporters the ability to make calls on his behalf, offering customized scripts; the other candidates limit outreach to donation requests and email and volunteer sign-ups. Moreover, it was rare for any of the three to repost material on social media from outsiders (there were almost no re-shares on Facebook and only about two-in-ten tweets from any of the candidates were retweets). Only Trump tended to include members of the public in his reposts: 78% of his retweets were from members of the public, compared with none of Clinton’s and 2% of Sanders’. Trump’s focus on the public also stands apart from 2012, when only 3% of Obama’s tweets during the period studied and none of Romney’s retweeted members of the general public.

On websites, citizen content is minimized or excluded altogether; in social media, Trump stands out for highlighting posts by members of the public. Unlike previous cycles, none of the sites offers the user the option to create a personal fundraising page, nor do their news verticals have comment sections. And only Sanders affords supporters the ability to make calls on his behalf, offering customized scripts; the other candidates limit outreach to donation requests and email and volunteer sign-ups. Moreover, it was rare for any of the three to repost material on social media from outsiders (there were almost no re-shares on Facebook and only about two-in-ten tweets from any of the candidates were retweets). Only Trump tended to include members of the public in his reposts: 78% of his retweets were from members of the public, compared with none of Clinton’s and 2% of Sanders’. Trump’s focus on the public also stands apart from 2012, when only 3% of Obama’s tweets during the period studied and none of Romney’s retweeted members of the general public.

None of the three websites featured any distinct section addressing specific voting groups or segments of the population – a popular feature of campaign websites in 2008 and 2012. In 2012, Obama’s campaign offered opportunities to join 18 different constituency groups, while visitors to Romney’s website could choose from nine different voter group pages. In 2008, both candidates offered around 20 such dedicated pages. In 2016, this feature is no longer present. There are still “issue” pages which explain the candidate’s position on certain issues but do not allow for longer-term ways for voters to identify with the candidate or connect with other supporters.

Facebook and Twitter usher in a new age in audiovisual capabilities. Candidates were already experimenting with regularly posting videos in 2008 and 2012 as YouTube increased in popularity, though to a minimal degree. By contrast, Clinton posted about five videos a day on Facebook and Twitter during the time period studied and embedded video in about a quarter of both her total tweets and Facebook posts. Trump, who averaged about one video a day on social media, was least likely to include regularly updated videos on either social platform (only 2% of his tweets, for example).