While print newspapers everywhere face difficult challenges in the future, newspapers in the United States today are suffering more acutely than those virtually anywhere else in the world. In sharp contrast with the U.S. situation, overall print newspaper circulation worldwide has dipped only slightly so far in 2010. Revenues are expected to rise, according to a new report from the Pew Research Center’s Project for Excellence in Journalism.

Print newspapers are suffering declining readership and revenue in most of the developed world, such as in Europe and Australia, though in general the problems are not as severe as in the United States, particularly when it comes to revenue.

But in much of the developing world, print newspapers are thriving, in some cases dramatically.

The distinction between whether a nation’s newspapers are suffering or flourishing depends in broad terms on whether the country is enjoying increases in population, education, literacy and income levels or is an already developed country with a mature newspaper industry, though some other factors appear to be relevant as well.

The problems are greatest, generally, in developed countries where newspapers already are consumed by large percentages of the population and where there are a lot of media providing news and information. Print newspapers are thriving, meanwhile, in countries with untapped and emerging population segments. In some parts of the world, such as India, reading a print newspaper is a prestigious activity, in much the same way that it was for immigrants a century ago in the United States.

In most developing countries print newspapers “are still growing,” said Robert Picard, media economist and director of research at the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism at the University of Oxford. But he warned that their gains may be temporary as those countries shift to new technologies. “Hopefully, they’ll take notice of what’s happening in our markets, and they’ll try to transform themselves.”

First, some basic numbers: In the United States, newspaper circulation fell by 10.6% daily and 7.1% on Sundays in the six months from March to September 30, 2009, compared with a year earlier, according to Audit Bureau of Circulations data. Europe saw a smaller drop, 5.6% during calendar year 2009 from the year before, according to data from the World Association of Newspapers’ 2010 World Press Trends report; Australia and Oceania fell 1.5%.

In Africa, by contrast, circulation in 2009 rose across the continent by 4.8%. Asia saw circulation gains of 1.03%, though the gains were concentrated at higher rates in places like India (nearly 5%). Worldwide in 2009, print newspaper circulation dipped 0.8% from a year earlier, (WAN, 2010). Yet overall, print newspaper circulation today remains up 5.7% worldwide from where it was five years earlier.

Determining Factors

Five factors seem to be at play in determining the health of a country’s newspapers or the severity of their problems.

The most important, and most obvious, is that in many of these nations or markets, rising literacy rates dovetail with growing disposable income to create millions of potential new readers. India’s literacy rate, for example, has grown from roughly one-third (35%) of the population in 1976 to 82% in 2009, according to Indian government estimates, (WAN, 2010). “There’s a hunger among Indians to know,” Bhaskara Rao, director of the Centre for Media Studies in New Delhi, told Agence France Presse in 2010.

Executives in India say reading a newspaper is considered something to aspire to instead of a throwback to a bygone era. “Anyone who can read or write is still looked at with a bit of awe” in parts of India, Rajesh Kalra, the editor of the Times of India’s Times Internet division, told The New York Times in 2008. The paper boasted a circulation of 3.5 million in 2008, 10% higher than it did a year earlier, and the paper planned to launch in new cities. Once people learn to read, they are proud of their new skill, Kalra said, and “the first thing you want to do is be seen to be reading a newspaper.”

The image echoes back to the United States in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, when papers were aimed explicitly at European immigrants, who felt similarly about newspapers and often held reading groups to have neighbors who knew English read the paper out loud. The newspaper comic strip was invented as a way for immigrants with limited language skills to find something in the paper they could follow. The term yellow journalism comes from one such comic strip, “The Yellow Kid,” about the adventures of an orphaned immigrant child, a metaphor for how immigrants in general felt in America.

The number of Indian dailies (not including free papers) rose by 44% from 2005 to 2009. Circulation during that period rose 40% (more than 8% in 2008 alone and 5% in 2009). The amount spent on advertising is growing, too, by nearly 19% in 2008 and 4.5% in 2009.

There are still signs in India’s newspapers face problems that afflict other modern societies. The percentage of readers who read the paper everyday is declining; the growth is in casual or occasional readers. Younger people who can read prefer the Internet. Costs are rising dramatically: Newsprint jumped in price by 50% in 2008, softening since then. But rising population, rising literacy rates and rising income levels are enough to mask those problems, or delay their reckoning.

“We do see a big potential in emerging markets,” John Ridding, chief executive of the London-based Financial Times told The New York Times in 2008. One other factor in India: The expected profit margin of newspapers is much smaller than in the United States, averaging around 10%, whereas U.S. newspapers in their better days expected double that.

A second factor, intertwined with economic development, is the state of the online penetration in a country. If the nation is not connected with broadband, and smaller levels of the adult population are online, the print industry is less threatened by new technology. According to the National Book Trust-National Council of Applied Economic Research’s National Youth Readership Survey, for instance, fewer than 4% of people between ages 13 and 35 in India have access to the Internet. However, there are several European countries, particularly in Scandinavia, where high levels of Internet use continue to coexist with high levels of newspaper readership.

The third factor is political. Countries with either evolving democracies or at least evolving capitalist systems tend to drive newspaper growth, which helps explain why Hungary (6.9%) Kosovo (12.5%) and Russia (9.3%) are also on the list of countries where newspapers are launching in bigger numbers, helping advertising revenue grow. Volatile as it is, Afghanistan also saw its paid daily newspaper titles jump 12.5% in 2009.

Still a fourth factor affecting the health of the newspaper industry is government subsidy. In several countries, the government offers substantial subsidies to help the newspaper industry thrive as a matter of public policy. The amount and nature of the subsidy can vary widely, and it is difficult to pin down how widespread the subsidies are—they are being scaled back in some places and increased in others. Ireland, for instance, has devoted hundreds of thousands of Euros per year to subsidize Gaelic-language press. Austria has pumped millions in recently to reduce distribution costs and to train journalists. Belarus spent $90 million on state media, but nothing on independent press. France has thrown a life raft to its newspaper industry lately, following up on advice that it work with its printers union to cut costs, and has discussed tax breaks for media innovations. To a degree, subsidies may mask the effects of changing technology. Some news industry executives also worry, however, that subsidies may inhibit innovation. In difficult times, they have argued, the instinct is to look to the government as the easiest and most risk free way of filling gaps.

A fifth factor is the economic structure of each country’s newspaper industry. American newspapers are more dependent on advertising, and the collapse of particular advertising sectors have affected them more.

The elements vary, however, by country, which makes some brief country case studies useful.

United States

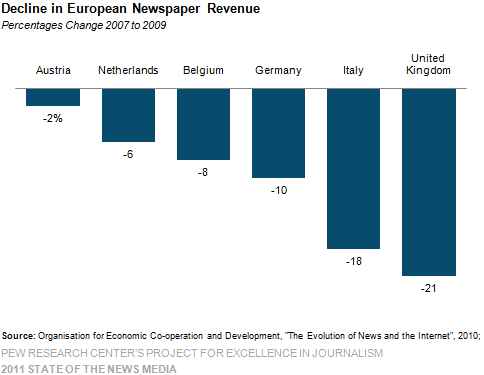

The U.S. newspaper publishing market has shrunk more dramatically in recent years than in much of the world as an ongoing downturn in newspapers met the global economic recession. From 2007 to 2009, U.S. newspapers saw an estimated 30% drop in revenues from online and offline circulation and advertising, outpacing other developed nations. By comparison, the United Kingdom saw a 21% drop during the same period, according to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. One reason U.S. papers have suffered more is they are more heavily dependent on advertising than papers in most other parts of the world. For instance, globally, advertising makes up 57% of overall newspaper revenues, while circulation makes up 43%, (OECD, 2010). By contrast, U.S. newspapers on average generate 73% of total revenue from advertising, selling the print copy for less to maximize readership they can deliver to local advertisers. To complicate matters, several U.S. newspaper companies in the last decade acquired heavy debt burdens, including McClatchy Company, Lee Enterprises and Freedom Communications. The much publicized bankruptcy proceedings into which several companies fell (including Tribune Company and Philadelphia Newspapers) generally reflect the difficulty of corporate parents to make bank payments rather than that the papers themselves are losing money. This is another difference with papers in other countries. “In the U.S., many companies were actually making money, but they couldn’t afford their debt. You haven’t seen that in Europe,” Picard said.

This means that the decoupling of advertising from news created by the advent of the web and afflicting U.S. papers hasn’t had quite such a devastating effect on the immediate economics of European papers. This “decoupling,” comes from several factors. First, free classified sites like Craigslist.org, or specialized classified sites like Realtor.com and Monster.com are wiping out classified advertising from U.S. print newspapers. Second, changes in American retailing, led by the rise of Big Box Stores like WalMart, affected newspapers in dramatic ways. These stores, which discount everything everyday and have low-price guarantees, do not tend to rely on print advertising, which is focused heavily on sales and promotions. WalMart thus advertises almost exclusively on television—the primary medium for image advertising. European retailing has not yet changed as dramatically as American retailing has.

Most American papers are also local. Of the 1,400 U.S. dailies, only three circulate nationally in print (the Wall Street Journal, The New York Times and USA Today). The rest serve local communities, and all but a handful are monopoly dailies in those communities. This is a primary explanation for the non-ideological nature of the U.S. print press and helps explain their dependence on advertising. But it also may inhibit their ability to raise their circulation rates with readers who might be more willing to support partisan press with high newsstand prices, according to some experts. “It’s hard to be radical with American newspapers because you don’t want to disturb the core of newspapers, but for newspapers that aspire to be national, there’s a huge potential,” said David Levy, director of the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism at the University of Oxford.

Europe

Most industry indicators suggest that, at the moment, European newspapers taken as a whole are not suffering as severely as those in the United States. But there are challenges. Between 2007 and 2009, for instance, newspaper revenue in most European countries shrank. Worst hit were the United Kingdom (-21%), Greece (-20%) and Italy (-18%), (OECD, 2010). Several factors have made things somewhat easier than in the United States, however. Again, a more limited reliance on advertising is one factor. Another is that many European newspapers are family owned and cushioned by private money during tough times. When the recession occurred, European newspaper companies felt the squeeze, but were still able to stay afloat and generally were not burdened by high debt. A third factor is that in many Northern European countries newspaper reading is significantly higher than in the United States historically, which has provided more cushion. In 2008, some nations even reported a small but notable increase in the percent of adults who claim to have recently read a newspaper, compared with previous years, including Iceland (96%), Portugal (85%), Switzerland (80%), Ireland (58%), Poland (58%) and Belgium (54%), (OECD, 2010). Even in the United Kingdom, where just 33% of adults report regularly reading a daily newspaper, that number is stable. In the United States, by contract, the reach is declining. U.S. newspapers had a daily reach of 45% for daily copies and 48% for Sunday editions, down from 55% overall daily newspaper reach in 2001 (OECD, 2010).

Those figures are borne out by circulation data. Circulation slipped in Europe by 5.6% in 2009 from the previous year but was not as dramatic as the 10.6% drop reported in the United States during that time. In Europe, newspaper sales, either at newsstands or by subscriptions, account for roughly 50-60% of all revenue, with advertising sales making up the remaining revenue (between 40-50%).

One interesting feature of the European newspaper industry is the prevalence of free newspapers, in which all revenue is advertising based. According to Rasmus Nielsen, research fellow at the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism at the University of Oxford, free newspapers in some countries represent as much as 40% of total newspaper circulation. Prior to the global recession, circulation of free newspapers had been particularly robust. In Russia, for instance, it grew by 523% from 2005 to 2009. In Romania, it rose 1,289% during that period. The recession seemed to blunt free circulation, in some countries more than others (World Association of Newspapers, 2010)

Some experts believe that more problems are coming. Cable, satellite and Internet trends that began to happen to the U.S. newspaper industry in the 1990s are starting to unfold in newspapers markets within Europe, media economist Robert Picard said. “They’re being hit by all the same trends in the United States, but they’re about 7-10 years behind us.” The percentage of newspaper advertising sales in Europe, compared against other media, reveals a mixed bag. For example, advertisers spent more in newspapers than in television, magazines, radio, cinema, outdoor media or the Internet in Sweden (42.9%, despite deep broadband penetration), Germany (37.4%), the Netherlands (33.5%) and the United Kingdom (28.4%). However, in the United Kingdom, this lead newspapers enjoy in advertising revenue is narrowly held over television (26.4%) and the Internet (23.2%). Meanwhile, television advertising sales dominate and more greatly resemble trends seen in the United States in Italy (49.9%), Poland (45.5%) and Spain (43.9%), according to a 2009 report from the Office of Communications in the United Kingdom. However, the Internet clearly enjoyed gains in advertiser spending in the United States and throughout most of Western Europe between 2007 and 2008, especially in the United Kingdom, where such spending grew 4.3%.

A nationally focused newspaper industry encouraged faster adoption of innovation to gain a competitive edge within the United Kingdom, Levy said. There, some willingness among newspapers to rise to the Internet challenge was tied to a need to meet the giant British Broadcasting Corporation as it went on to develop the most popular content website outside of social networking in the United Kingdom. “People have had to think about how you create a product that appeals to quite a broad market. The size of the country means you can’t be complacent about limiting yourself just to core readers,” Levy said.

Some European nations have also blunted some of the advertising problems through government subsidy, though many believe that is only delaying the problem rather than solving it. Direct subsidies to newspapers produced positive, short-term results in some European markets, but no research shows that subsidies offer long-term benefits for the industry. Picard pointed out that once politicians vote for newspaper subsidies that are not often designed to keep pace with inflation, the industry is forgotten for decades. The effect that newspaper subsidies create prompts the question: Is a slow death better than a quick one?

Beyond long-term effects, questions also have emerged about the legality of some government subsidy programs for newspapers. For roughly four decades, Sweden has used subsidies to preserve media competition found in cities with at least two newspapers. The Swedish system of newspaper subsidy distribution fell under sharp criticism in 2009 from the European Commission, which monitors competition within European Union member nations. The commission charged that these subsidies skewed market forces and provided large newspapers in major metropolitan areas with too much aid. “In mid size or small cities it’s fair to assume that the second one would die after a while without the subsidy,” Levy said. The democratic function of the subsidy succeeded to some degree, allowing for a more competitive marketplace of ideas, Picard said.

Despite the presence of government interventions and greater, more reliable circulation gains in Europe, some European nations experienced devastating losses in the percentage of newspaper publishing jobs. Among nations that saw the deepest cuts between 1997 and 2007 were Norway (-53%), the Netherlands (-41%) and Germany (-25%), (OECD, 2010). At the same time, other nations that saw, in some cases, very dramatic gains in newspaper publishing employment included Spain (63%), Poland (30%), Ireland (17%), and the United Kingdom (1%). These figures provide one more illustration of how much variance exists among European newspaper publishing markets and how perilous generalizations can quickly become. In Central and Eastern Europe, recent research suggests a notable absence of on-the-job training for journalists who do remain in the workforce, as well as a shift toward tabloid-style content that is easier to churn out than in-depth, investigative reporting (Center for International Media Assistance, 2011). On a more fundamental level, newspaper executives’ quest for more revenue streams or business models may be short-sighted given the challenges and changes that face the media industry in general. “You won’t find new business models if you’re not willing to change the product,” Levy said. “The problem with newspapers is that, sometimes, people are looking more from producer’s perspective than consumer’s end.”

In France, for instance, some problems echo those in the United States, and some do not. Circulation of French newspapers overall fell by 5% in 2009, but that followed an increase the year before. Advertising revenues for daily newspapers also declined nearly 19% in 2009, compared with the year before. The loss of younger readers is one concern, and President Nicolas Sarkozy tried to encourage the newspaper readership in January 2009 by announcing that every 18-year-old in the country would get a free one-year subscription to the paper of his or her choice. In 2010, France announced that it would enter a second phase of this program. More than one in every 10 French newspaper consumers were ages 15 to 24 in 2009 (WAN, 2010). He also gave French newspapers 600 million euros in emergency aid in addition to existing subsidies. Yet the more immediate problems facing the industry differ than in the United States. Le Monde, the center left daily considered the country’s paper of record, has been plunged into the worst crisis since its creation in 1944. In 2008, it reported losing more than $3 million a month and had plans to cut a quarter of its news staff (WAN, 2009). The problem, however, is not primarily declining circulation or even advertising revenues. The problem for French newspapers, especially the more serious ones, is cost. Only members of the print union known as Le Livre are allowed to work in the five print shops legally permitted to produce newspapers in the country, where costs are double those in non-union print shops in France. The other problem, as it is in the United States, is that French papers are losing money online, and their costs there are rising as they chase the changing tastes of audiences.

In England, the problems may seem even more familiar to those we know in the United States, but there are still some differences. Overall, circulation dropped 7% among paid-for daily newspapers. Losses at 2% were less severe among free dailies. The 10 national newspapers saw copy sales drop nearly 20% from 2000 to 2009, according to the Audit Bureau of Circulations (WAN, 2010). The economic recession did not improve the situation. Every regional paper in the country with paid circulation lost readers in 2008, according to ABC figures, and in 2009, several regional newspapers closed their doors for good while free papers gained in audience. Advertising revenues for print fell 17% in 2009, continuing a five-year decline of more than 28%. The British press already had a populist tabloid press of the sort only now developing in France, and the cost structure of British papers is not as onerous. The audience migration online and the difficulty of finding a way to monetize the web, however, remain.

Asia and Developing Markets

While the newspaper industries in United States and parts of Europe struggle to attract and retain readers, newspapers in many developing markets around the world enjoy boom times, thanks in part to increased literacy rates, improved employment opportunities and more disposable income. Circulation in Africa in 2009, for instance, rose across the continent by 4.8%. Asia overall saw circulation gains of 1.03% and is home to 67 of the 100 largest newspapers in the world. The gains were found at greater rates in nations such as India (5%), Afghanistan (7%) and Qatar (4%). South America saw circulation bump up 1.8% in 2008, but then its newspapers saw a 4.6% drop in circulation in 2009, (WAN, 2010).

A closer look at Asia by country, however, reveals newspaper industry complexities and demonstrates how quickly generalizations can be weakened even when looking at neighboring nations. For example, Japan and the Republic of Korea both support relatively mature newspaper industries and saw slight decreases in their newspaper circulation (OECD, 2010).

In Japan, the problems are more similar to the United States. Young people are moving to the Internet—and to free papers. The result is declining circulation (paid dailies down 2.2% in 2009) and declining ad revenue (down 15% in 2008 compared to the year before). But surging production and newsprint costs in Japan make these problems far worse. Industry net profit has been falling rapidly, down 91% in 2008 after dipping 33% in 2007, as the papers are unable to cut staff and to keep up product quality. Unless costs can be managed, something has to give. Meanwhile, newspaper daily reach in Japan, while it has fallen slightly, still sat at an enviable 92% of the adult population in 2008. In fact, 90% of people in Japan said their preferred form of media was a newspaper, The Japan Times reported in 2010.

The Republic of Korea outlines a different set of issues for print media, especially as more newspapers develop and invest in online platforms. Print circulation has held fairly steady. Between 2005 and 2009, print circulation dropped only 2%. But changes are certainly ahead. South Koreans spent less time reading newspapers in 2008 (37 minutes per day or recently) compared to just three years earlier (45 minutes). The nation is the world leader in providing high-speed, wireless Internet connectivity to virtually every household, and since the arrival of widespread online access to news and information, more South Koreans now prefer to get their news online (77.3%) than from newspapers (51.5%), (OECD, 2010). Meanwhile, the number of online editions of South Korean newspapers rose nearly 500% between 2005 and 2009.

Again, India stands in contrast to nations like Japan and Korea. The evidence suggests rising literacy rates were clearly one factor in this growth, not only in India, but also in other developing markets. Literacy rates among adults in Asia on average jumped from 69.8% (1985 to 1994) to 81.5% (2005 to 2008), according to data from the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. During the same time periods in Africa, the literate adult population grew from 52.1% to 63.4%. By comparison, the literacy rate in North America and Europe is 95%.

And the increases in literacy and education are often accompanied by rising economic status. In places like India and China, the rise of the middle class fueled interest in picking up newspapers, said Tom Plate, an author and former Los Angeles Times columnist and UCLA Asian media professor. Another factor in developing countries, Picard said, is that print does not have to compete as much with other media, particularly broadcast. For example, newspaper editor and CEO Sanjay Gupta told The Hindustan Times that he maintains that print will continue to dominate India where 5% of the population has access to the Internet. Similarly, 5% of Kenyans ages 15 or older log onto the Internet daily, and 38% of Kenyan households have a television set, the Columbia Journalism Review reported in 2009. Therefore, it may not be surprising that a single newspaper copy generally is read by 14 people. Overall, these markets have not yet matured, but they might expect to contend with similar issues in 10 to 20 years, Picard added.

Print’s relatively stable days in developing markets also may be numbered. The potential for online news delivered via net-by-text cloud-based services, which is opening the door for people to access the Internet via mobile phone, is enormous. Also, Internet usage grew 14.49% worldwide in 2009 from a year before, (WAN, 2010). This was especially true in Africa (36%) and Asia (19%). Cell phone subscriptions grew 15.8% globally in 2009, with Asia seeing the largest spike (21.6%), followed closely by Africa (20.7%).

China, as always, is a unique case. Local and regional newspaper companies in China are consolidating into publicly traded national or inter-regional cross-media companies. Circulation overall rose at more than 10% for paid newspapers between 2005 and 2009, and newspaper advertising is growing, up 6.4% in 2008 (WAN, 2009, 2010). Interestingly, the ad revenues of other media are growing even more rapidly. Magazines, an industry in turmoil in the United States, saw the highest ad revenue growth in 2008, up 17.2%. Only 23% of the population is online, a third of the rate in the United States. However, Internet use is on the rise in China with 384 million online in 2009, compared with 239.8 million users in the United States (WAN, 2010). As people gain more funds and become more acquisitive, print remains a medium of delivery.

At the same time, the country is discovering the implications and perils of commercial advertising. The government in 2008, for instance, alarmed by actors and celebrities making claims in medical and drug advertisements, issued a circular banning such endorsements or any ads making claims about cure rates. A separate government ministry issued orders for media companies to exercise more censorship of advertising in other ways, and moves are coming to rewrite the broad laws governing advertising. Also, China continues to censor media through state filters.

The Future

If the developing world with growing populations is seeing newspapers thrive, most developed nations are suffering. The view in most places around the world is not that they are immune to the problems of American newspapers, but rather that the U.S. industry is ahead of them in navigating a dangerous curve. While they are not suffering from the immediate loss of advertising as American newspapers are—particularly the vanishing of classified—they can see their audience is moving online, as well as to television and satellite news channels. If not in the next two or three years, probably in the next five or ten, they will be faced with exactly the same problem we are. How can you monetize the audience that has gathered on the web? What are the prospects for charging for the content there? What are the trends in advertising online? What do the data tell us about the other prospects for revenue online beyond advertising or subscriptions?

The mistakes and the triumphs of American journalism will be the laboratory for these media elsewhere. And in places like India, a country that is both developed and developing at the same time, they may both learn from the American experience and probably leap ahead.

“We have to understand,” Picard said, “that when you have changes taking place in society, newspapers are going to follow them, consumption’s going to follow them, and how you fund papers will change a great deal.”

About This Report

The Project for Excellence in Journalism used three main methods to perform a qualitative, comparative analysis of the newspaper industry in the United States and nations elsewhere. Data that provided the greatest amount insight into this subject were found in the World Association of Newspapers 2010 and 2009 World Press Trends reports, as well as literacy data from the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. A literature review included information from the Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development’s 2010 ‘The Evolution of News and the Internet’ report, the (United Kingdom) Office of Communications ICMR 2009 Statistical Release, Center for International Media Assistance’s 2011 ‘Caught in the Middle: Central and Eastern European Journalism at a Crossroads’ report, National Book Trust-National Council of Applied Economic Research’s National Youth Readership Survey, as well as popular press reports from The New York Times, Agence France Presse, The Japan Times, The Hindustan Times and the Columbia Journalism Review. Finally, interviews with David Levy, Robert Picard and Rasmus Nielsen, all of the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism at the University of Oxford, as well as author Tom Plate, offered valuable perspective and analysis of trends in the newspaper industries in the United States and abroad. Levy, Picard and Nielsen also reviewed the manuscript and offered feedback.