Faced with shrinking revenue and dwindling audiences, news organizations in recent years have slashed staffs and reduced coverage. Most news consumers are little aware of the financial struggles that led to these cuts, a new Pew Research Center survey finds. Nevertheless, a significant percentage of them not only have noticed a difference in the quantity or quality of news, but have stopped reading, watching or listening to a news source because of it.

Nearly one-third—31%—of people say they have deserted a particular news outlet because it no longer provides the news and information they had grown accustomed to, according to the survey of more than 2,000 U.S. adults in early 2013. And those most likely to have walked away are better educated, wealthier and older than those who did not—in other words, they are people who tend to be most prone to consume and pay for news.

The findings represent one more piece of bad news for organizations already laboring to secure their place in the 21st century.

Despite the audience recoil, the majority of people surveyed early this year had heard little or nothing about the financial problems besetting news organizations. The largest group of respondents—36%—said they heard “nothing at all” about the issue and the second largest—24%—said they heard “a little.” That combined total of 60% far overshadows the 39% of people who said they heard “a lot” (17%) or “some” (22%) about the financial woes of the news industry.

While a majority of people don’t sense a connection between the news media’s financial strains and quality reporting, a significant minority do detect a direct connection between the two. Fifty-seven percent of the respondents who had heard at least a little about the financial struggles said they didn’t think the situation had much of an impact on the media’s ability to cover local, national or international news. At the same time, about one-third—35%—said the problems have made it more difficult to cover local news, while a similar 37% said they have made it harder to cover national and international news.

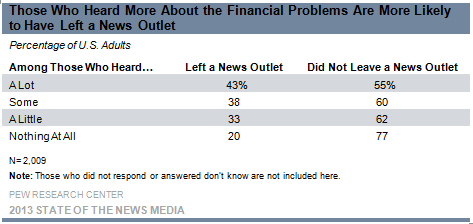

Perhaps more ominous for news outlets, those who are more aware of the financial problems and those who see a connection to reporting are the people most likely to have abandoned an outlet because it no longer provided them with the news and information they relied on.

In other words, people most acutely familiar with the economic struggles are the most likely to lose their patience with a news outlet: 43% of the people who said they heard a lot about the financial troubles stopped turning to a news outlet because they were dissatisfied with what they were getting. That was true of just 20% of those who heard nothing about the problems. Likewise, 45% of the people who said the financial problems made it more difficult for news outlets to cover local, national or foreign news abandoned an outlet, compared to about one-third of those who did not see much of an impact.

People who said they had forsaken a news outlet were more likely to be men than women, older than younger, richer than poorer and Republican or independent rather than Democratic. While about one-third of Republicans and independents stopped turning to a news outlet, just one-quarter of Democrats did.

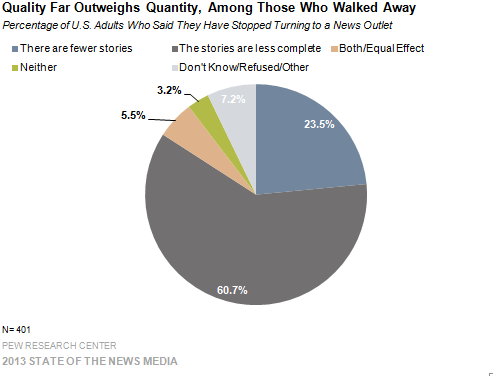

What’s more, the primary concern for people who gave up on an outlet seems to be quality. When asked which they noticed more, fewer stories or less complete stories, far more people said the latter (24% to 61%). While reduced thoroughness in stories was the more prevalent response among adults overall who were aware of the struggles, the split was not nearly as wide – 48% versus 31%.

Most Adults Have Heard Little About the Financial Problems

Still, the majority of those who have heard something about the financial strains don’t think they harm news coverage—a somewhat striking finding given the tens of thousands of layoffs and buyouts that have occurred in newsrooms throughout the country the past several years.

The newspaper industry alone shed 28% of its employees since its peak in 2001, according to The American Society of News Editors’ annual newsroom census, and in 2012, that number is estimated to have dipped below 40,000 employees for the first time since the census began in 1978.

From 1998 through 2010, eighteen newspapers and two newspaper chains closed all of their foreign bureaus, according to a tally by American Journalism Review. Other outlets reduced the number of correspondents in their bureaus.

In Washington, news organizations have drastically reduced their coverage of the federal government and some of its most visible departments, such as State, Defense, Justice and Treasury, AJR reported. For instance, in 2003, 23 reporters covered the Pentagon. Seven years later, 10 did. During the same period of time, reporters covering the State Department dropped from 15 to nine. Financial pressures also have led to a sharp reduction in the number of reporters who travel with the president in the United States and abroad.

Who is Aware of the Turmoil and Sees and Impact

In the Pew Research poll, certain categories of people were more aware than others of news outlets’ financial problems. People 65 and older, college graduates, those who earned more than $75,000 a year and residents of the Northeast were more likely to have heard something about the situation than people who were younger or less educated, those who earned less money or those who lived in other parts of the country, particularly the Midwest.

Nearly half—46%—of people 65 and older said they had heard “a lot” or “some” about the financial problems, compared to 35% of 18- to 29-year-olds and 38% of 30- to 49-year-olds. In fact, a full 42% of 30- to 49-year-olds said they had heard “nothing at all” about the issue.

Half the people with annual incomes of more than $75,000 said they had heard “a lot” or “some” about the media’s financial woes. That figure declined as income did, with slightly less than one third of people who earned less than $30,000 asserting at least some knowledge of the problems. Nearly half—47%—of residents of the Northeast, the most media-saturated part of the country, said they had heard “a lot” or “some” about the situation, compared to 40% of people in the South or West and just 33% of those in the Midwest.

Those who were older and more educated were also more likely to tie the financial struggles to greater difficulty reporting local news. College graduates who had heard at least a little about the financial difficulties were most likely to say they hurt local coverage, at a rate of 43%, compared to 32% of people with some college education and 31% who did not attend college at all. Among the various age groups, 40% of respondents aged 50 to 64 who heard at least a little about the financial constraints felt they made it more difficult to cover local news, as did 38% of people 65 and above. But less than a third of people under 50 answered that way.

When it came to national and international news coverage, demographic differences were less pronounced. The most conspicuous gap was a partisan one: 39% of Democrats who had heard at least a little about the financial situation said it made reporting harder, compared to 31% of Republicans. African Americans were most likely to say money did not have much of an impact on coverage, at 67%, compared with 56% of whites.

Quality versus Quantity

To gauge the public’s view of how the financial travails have affected news coverage, the survey asked people whether they thought news stories were less complete than they used to be or whether there simply were fewer of them. This goes to the issue of content, and pits quality against quantity. About half—48%—of respondents said stories are not as thorough as they were before, while slightly less than a third—31%—said stories are fewer.

The sense that thoroughness was a bigger problem than the quantity of stories carries across all demographics, though it was more pronounced among Republicans, independents and Southerners and less so among Democrats and Midwesterners. This comports, in part, with political divisions in the country. Men tend to vote in greater percentages for Republicans and women for Democrats.1 The South is dominated by Republicans; the Midwest is divided.

What stands out even more is the degree to which people who left a news outlet they were dissatisfied with blamed a reduction in the quality of reporting. Fully 61% of them said stories were less complete than they had been versus just 24% who complained there were too few stories. For those who have not abandoned a news outlet, the breakdown is much more even.

So what do these findings mean for news organizations? It is clear from these data that much of the country recognizes little if anything about the economic challenges the industry is grappling with—and that much of the knowledge and concern about the economics and the future of the news business may be largely confined to the industry itself. But the news consumers who are more aware of the problems and their impact on news are more likely to act on those concerns by abandoning a news organization. And, based on demographics, they also are likely to be more ardent news consumers who are willing to invest in a product they value.2 They appear to be making informed choices. The job of news organizations is to come to terms with the fact that, as they search for economic stability, their financial future may well hinge on their ability to provide high quality reporting.

Methodology

The PSRAI January Week 4 and February Week 1 2013 Omnibus Polls obtained telephone interviews with a nationally representative sample of 2,009 adults living in the continental United States. Telephone interviews were conducted by landline (1,003) and cell phone (1,006, including 512 without a landline phone). The surveys were conducted by Princeton Survey Research Associates International (PSRAI). Interviews were done in English by Princeton Data Source from January 24 to 27 and February 7 to 10, 2013. Statistical results are weighted to correct known demographic discrepancies. The margin of sampling error for the complete set of weighted data is ± 2.5 percentage points.