On Tuesday Feb. 28, Mitt Romney edged out a win the Michigan primary over Rick Santorum by a 41%-38% margin. A loss in his native state would have triggered significant doubts about Romney’s candidacy. The narrow victory also could have been portrayed as a frighteningly close call. In the media narrative, however, it proved to be a decisive moment in his quest for the nomination.

From that point on, what had largely been mixed or negative press coverage of Romney in 2012 took a dramatic turn for the better and stayed that way until he had a virtual lock on the nomination. Romney also began to separate from the rest of the GOP field in the amount of attention he received in the press.

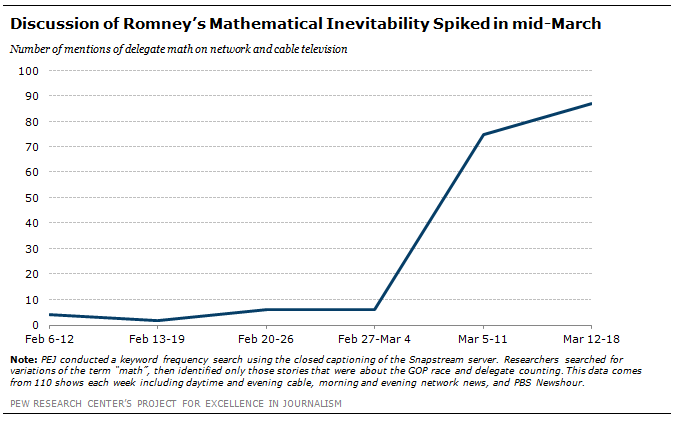

A close look at the coverage reveals that after Michigan, the press began to talk in significant terms about the mathematical inevitability of Romney winning, given new rules set up by the Republican Party apportioning delegates by vote count rather than winner take all.

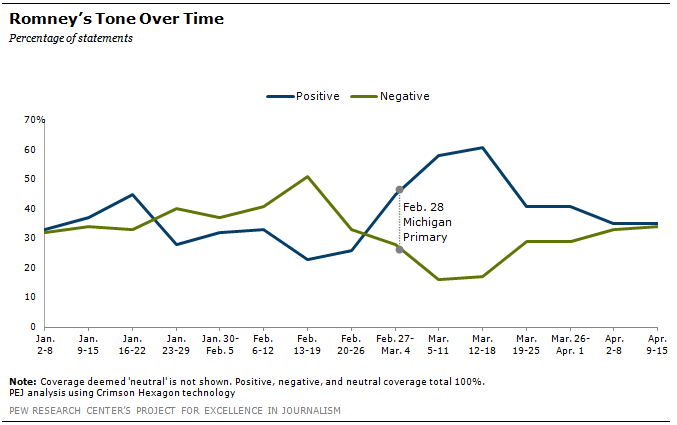

Until that point, for most of the primary and caucus season, the tone of Romney’s news coverage vacillated primarily between mixed and unflattering. He enjoyed one week of clearly positive coverage (45% positive, 33% negative) in the week following his solid, if widely expected win in New Hampshire on Jan. 10.

But that media bounce was short lived. The week of his loss on Jan. 21 to Newt Gingrich in South Carolina, negative coverage of Romney (40%) outstripped positive (28%) by 12 points.

His coverage improved some after his win in Florida on Jan. 31, but not overwhelmingly so. Romney still had to contend with the media meme that he could not “close the deal” against a weak field of opponents. And throughout February, his coverage was more consistently more negative than positive. It reached a nadir the week of Feb. 13-19 (23% positive and 51% negative) when Romney was still reeling from losses to Santorum in the Feb. 7 contests in Missouri, Colorado and Minnesota.

Then came Michigan, where Romney overcame a Santorum lead in the pre-election polls to pull out the win. The week of Feb. 27-March 4, Romney’s positive coverage shot up to 45% (from 26% the week before) and his negative coverage dropped to 28% (from 33%). In the next two weeks, which included his six wins in the March 6 Super Tuesday voting, Romney enjoyed by far his best coverage of the year, with positive assertions about his campaign exceeding negative ones by more than 40 percentage points.

A keyword search of the coverage finds this sudden shift in tone about Romney coincided with a shift in the subject matter. An analysis of television news programs studied by PEJ each week reveals that the week after Michigan, references in the press to terms such as “delegate math” and “mathematical inevitability” increased twelve fold.

The first week of April, the tone of coverage of Romney changed again to something more mixed—35% positive, 33% negative, 32% neutral. Again the storyline had changed.

In April, the press was no longer focused on Romney’s chances against GOP rivals. Instead, more of the narrative focused on criticism of Romney from the Obama campaign and Romney’s perceived chances against the sitting President.

In the media narrative, for all intents and purposes, the general election had begun.

Romney’s victory in Michigan also marked something of a milestone in the competition for attention from the media. During the first eight weeks of the primary season, Romney was often closely rivaled or even bettered in amount of attention he received. PEJ monitors attention by measuring the number of stories in which a candidate is a significant presence—meaning he is featured in at least 25% of the story.

Following Michigan, Romney remained the top GOP newsmaker week after week.

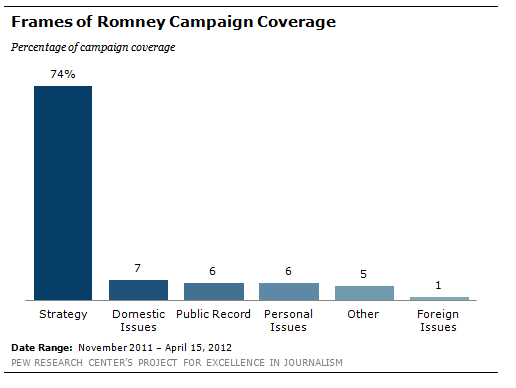

This post-Michigan shift is also evident in the frame of Romney’s coverage. In this case, it was a move away from his public record and his personal background to coverage that focused more heavily on the horse race.

In November and December of 2011, for instance, 15% of the coverage about Romney focused on his past public record and his personal life. They ranged from discussion of his Mormon religion to criticisms that he had changed positions on key issues during his career—the so-called flip flopper issue that has dogged him.

In the first two months of 2012, that vetting continued, accounting for 14% of the coverage about him, although the topics changed. On the personal side, the release of his income taxes and his substantial wealth became a significant story. On the public side, there was attention to his venture capital firm, Bain Capital, as a debate raged over whether its investments primarily benefitted the overall economy or a few wealthy businessmen.

From March 1 through April 15, the vetting of Romney’s public and personal life fell to 5% of the coverage about him.

The amount of coverage of Romney’s positions on policy issues see-sawed over the past five and a half months. In November and December, policy accounted for 9% of his coverage. It dropped to 6% in January and February. Policy coverage involving Romney then peaked (at 12%) from March 1 to April 15 as the health care debate, and the law Romney enacted while governor of Massachusetts, began to attract more attention.

For the full 15-week primary period, 74% of the coverage of Romney was focused on strategy, tactics, advertising and fundraising; 8% on his policy positions; 6% on his public record; and 6% on his personal background.