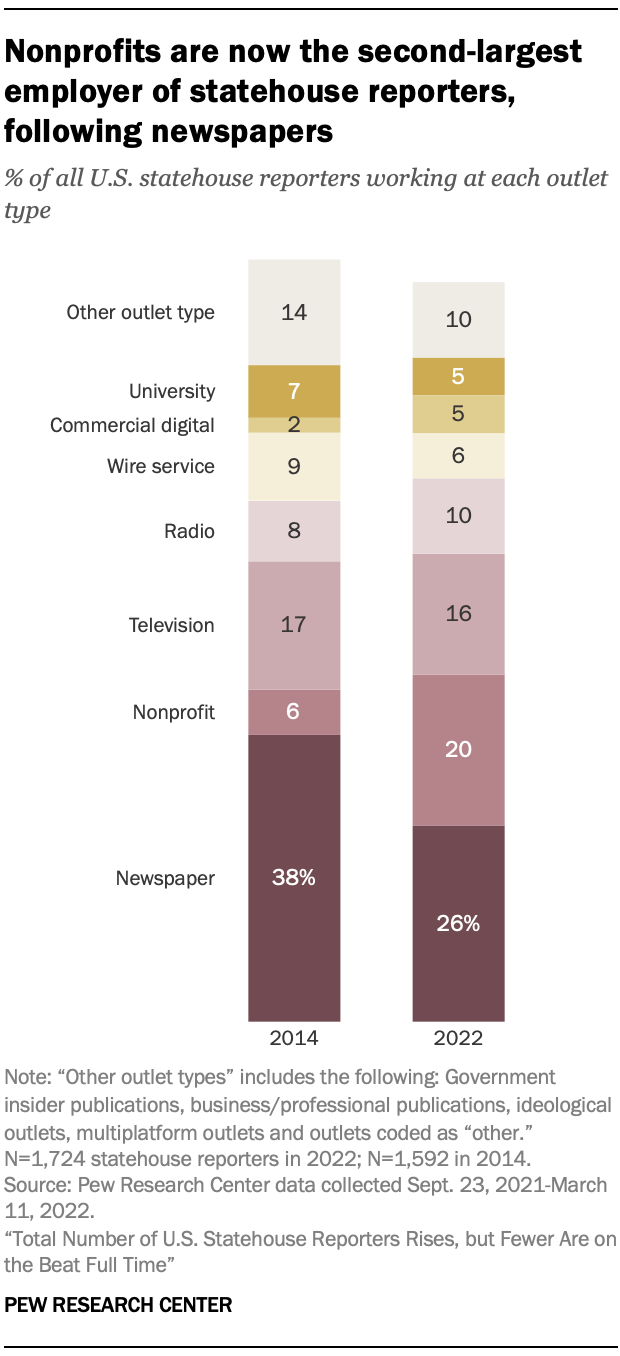

The 1,724 reporters covering the nation’s statehouses work for a range of outlet types. In 2022, nearly half work for either a newspaper (26%) or a nonprofit news organization (20%).

Television stations are the next biggest employer, with 16% of statehouse reporters. The rest of the statehouse pool works for radio stations (10%), wire services (6%), commercial digital sites (5%), university publications (5%) or other outlet types (10%), such as professional trade publications, alternative weeklies or magazines.

Nonprofit statehouse reporters now account for a far larger portion of all statehouse reporters than they did in 2014: One-in-five statehouse reporters work for a nonprofit news outlet, compared with just 6% in 2014.

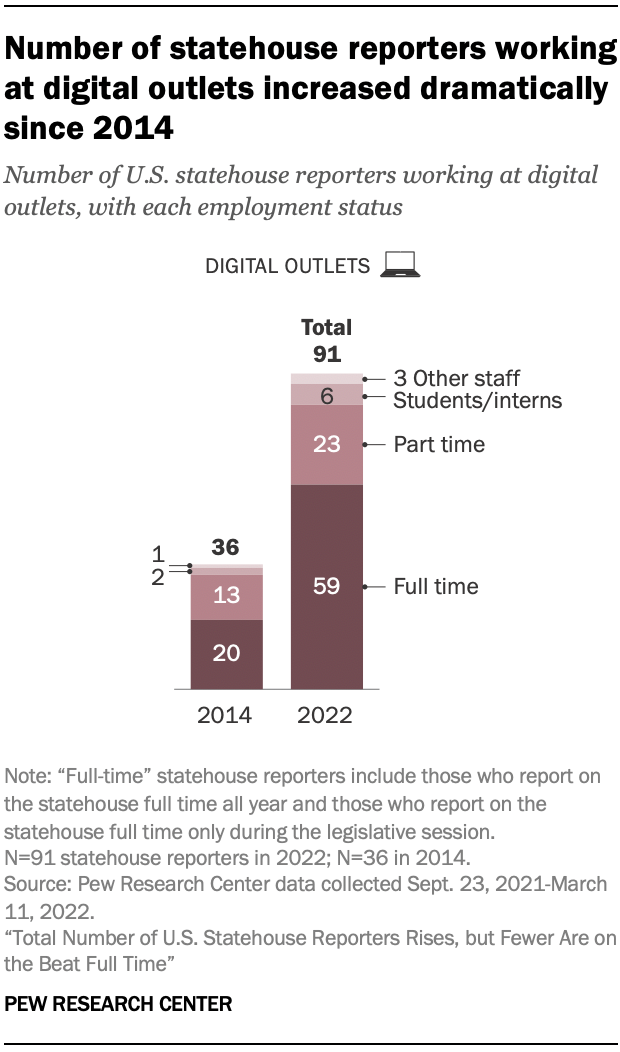

Commercial digital sites also grew, roughly doubling their share of the statehouse reporting pool, though they still make up just 5% of statehouse reporters (compared with 2% in 2014).

While newspapers are still the biggest employer of statehouse reporters, their staffing contribution has declined. As of 2022, newspaper statehouse reporters constitute 26% of the statehouse corps, down from 38% in 2014.

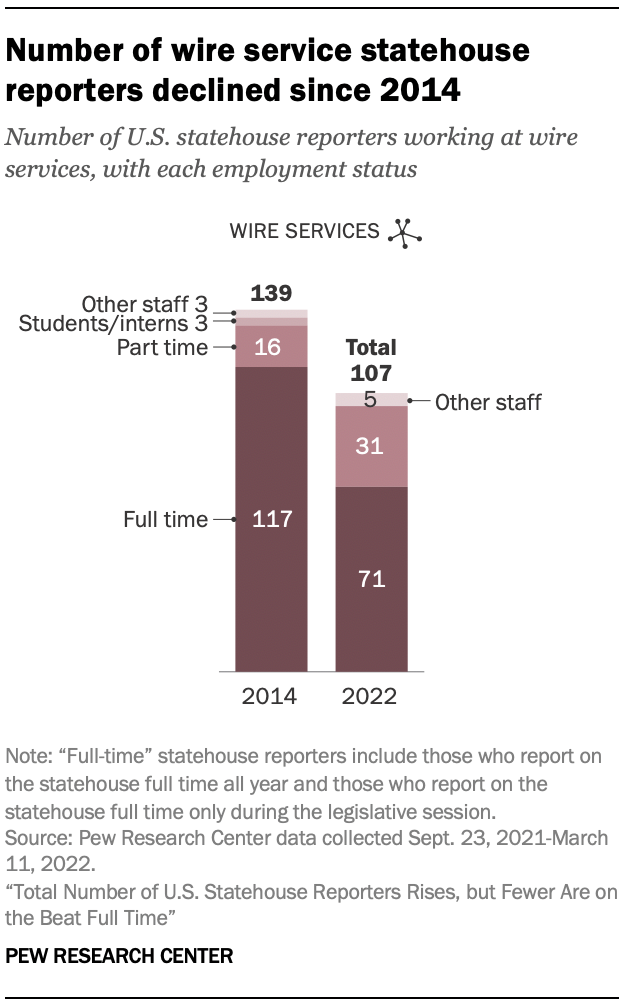

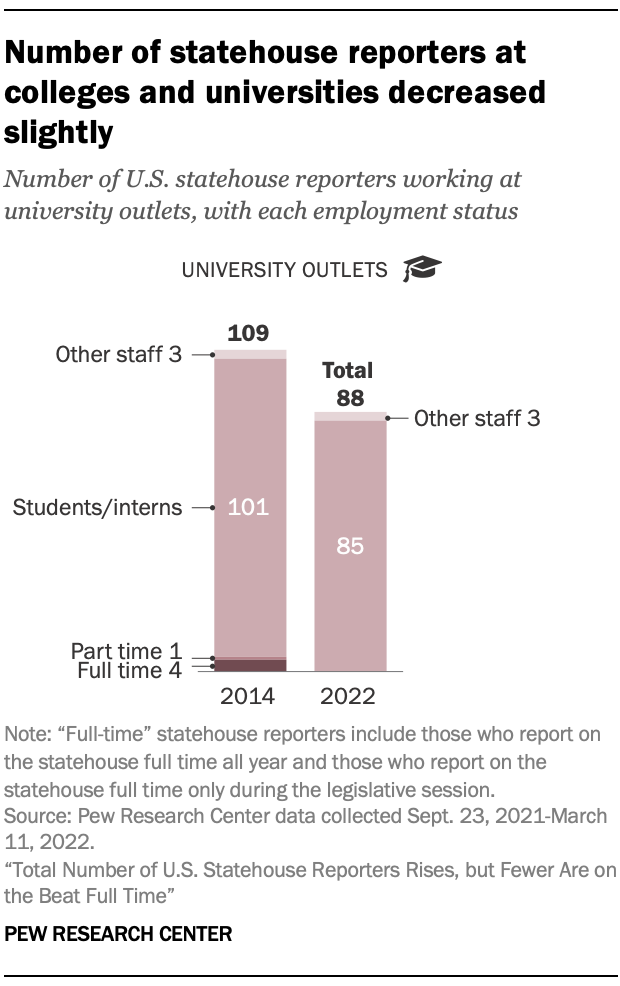

Wire services also make up a smaller portion of the total (6%, or 107 reporters) than in 2014, when they made up 9% of the total, or 139 reporters. Reporters from university outlets also have declined slightly as a share of the total (from 7% to 5%).

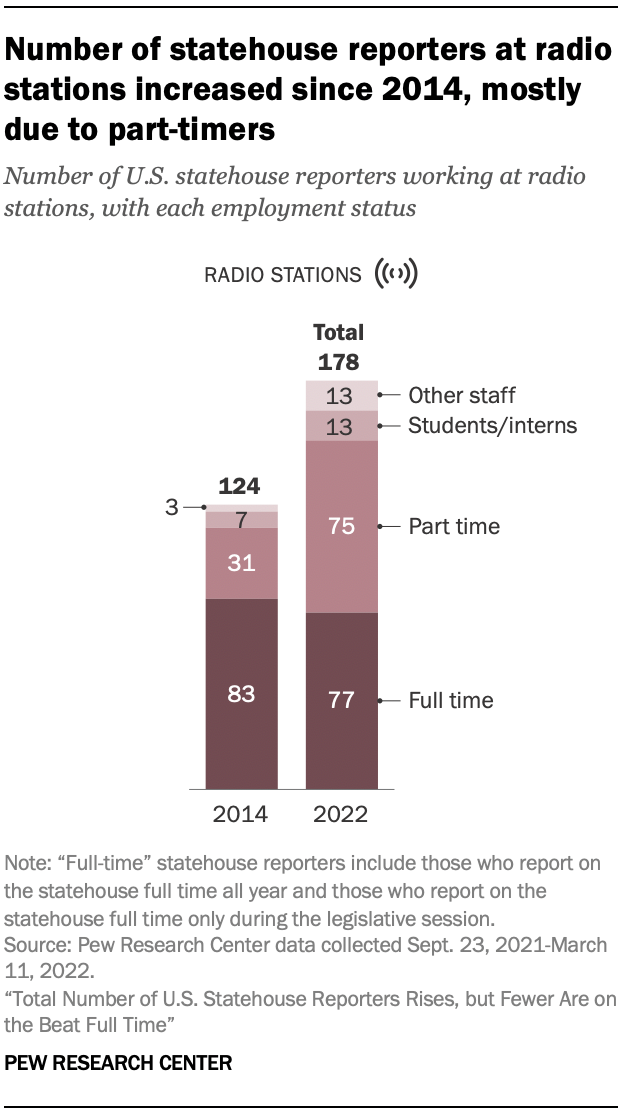

Other types of outlets account for about the same share of the statehouse reporting pool as in 2014, with a slight increase in their total numbers. For instance, TV reporters make up 16% of the total (283 reporters), about on par with 2014 (17%, 263 reporters). And statehouse reporters from radio stations currently make up 10% of the total, compared with 8% in 2014 – again with an increase in total numbers (from 124 in 2014 to 178 in 2022).

The rest of this chapter looks at reporters from each outlet type in greater detail.

Newspaper: Legacy newspapers with a substantial print presence.

Nonprofits: Nonprofit news organizations. These outlets are typically digital but are not included in the commercial digital category due to their nonprofit status. Public radio and television stations are included in the “radio” and “television” categories respectively. Nonprofit university outlets are included in the “university” category. A small number of nonprofit outlets that have an explicitly stated ideological stance are categorized as “other” (ideological).

Television: Television stations and networks.

Radio: Radio stations and networks, including public radio stations.

University: Outlets based in colleges or universities, typically staffed by student reporters.

Wire service: News agencies that supply syndicated news to other outlets. Both national and locally focused.

Commercial digital: Outlets whose primary mode of publication is digital and are not a nonprofit. A small number of digital outlets that have an explicitly stated ideological stance are categorized as “other” (ideological).

Other: Includes newsletters and websites aimed at government insiders or other news publications; business/law journals and professional trade publications; outlets with an explicitly stated ideological stance; alternative weeklies; freelance reporters; and the few outlets that publish and have statehouse reporters on multiple platforms, such as a television and radio station that share a statehouse reporter.

See the Methodology for more details.

Newspapers

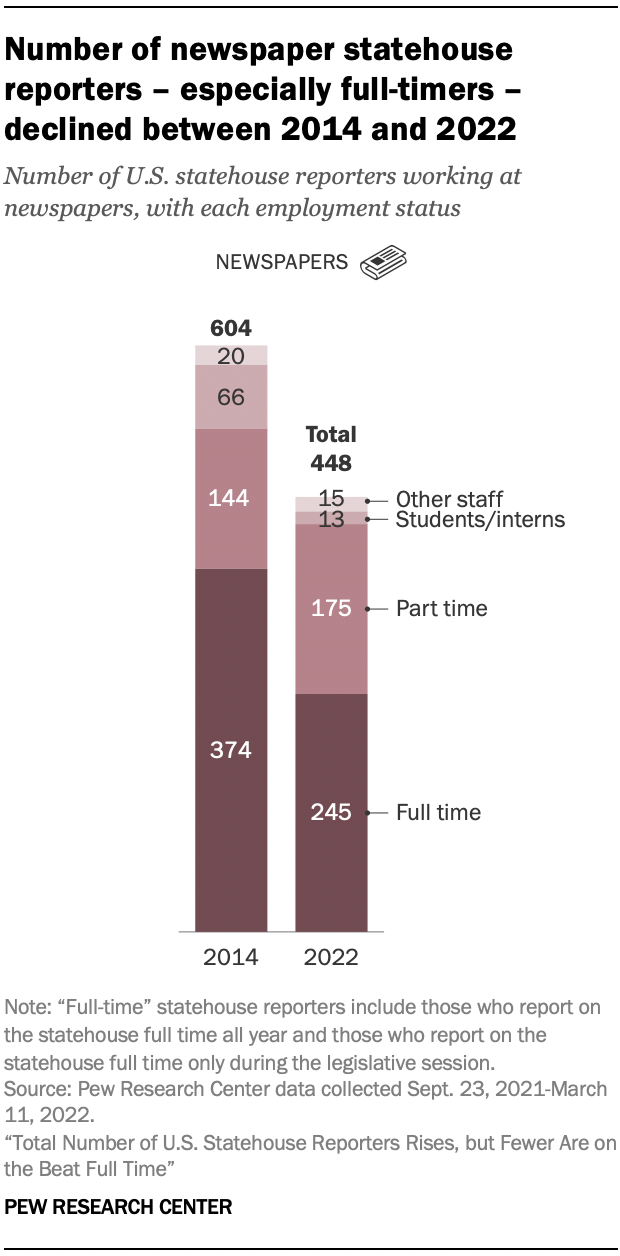

Newspaper reporters constitute the largest segment of both the total statehouse news corps (26%, or 448 reporters) and full-time statehouse reporters (29%, or 245 reporters). Still, the number of statehouse reporters working for newspapers has fallen considerably in recent years.

Between 2014 and 2022, the total number of statehouse reporters from newspapers fell by about a quarter, from 604 to 448 (a 26% decline). The number of newspaper reporters who cover the statehouse full time dropped by about a third, from 374 in 2014 to 245 in 2022, and the number of students and interns covering state government for newspapers fell by 80% (from 66 to 13).

Marianne Goodland, chief statehouse reporter at Colorado Politics, has witnessed the decrease in newspaper reporters in the Colorado statehouse. When she started there nearly 25 years ago, “you had all these newspapers, and all of them daily print publications,” she recalled. “We probably had nine or 10 newspapers that had reporters who were there every day. Almost all of those papers don’t have people at the Capitol anymore.”

This drop in statehouse reporting resources is reflective of the newspaper industry’s ongoing economic crisis. From 2014 to 2020 (the latest data available), newsroom employment at U.S. newspapers fell 33% – from roughly 46,000 jobs to about 31,000.

Still, some newspapers are newly prioritizing statehouse coverage. Janis Ware, publisher of the Atlanta Voice, said that although the African American-focused outlet was founded in 1966, the decision to have someone report on the statehouse is a relatively new one. “Sometimes I think we have to recognize that what is done at the state [level] controls everything.”

The statehouse cutbacks at newspapers are not uniform across the country. Statehouse staffing among newspapers fell in 32 states between 2014 and 2022, while it increased in 14 states and remained the same in four states.

Nonprofit news organizations

What is included in the ‘nonprofit’ category

The outlets in this group all have a nonprofit status. Some of these nonprofits publish only online but are separate from the commercial digital category because they are not commercial (i.e., not-for-profit). Additionally, a small number of nonprofit outlets that have publicly stated political orientations or policy goals (by themselves or their parent organizations) are counted in a separate “ideological” category below, not in this nonprofit category.

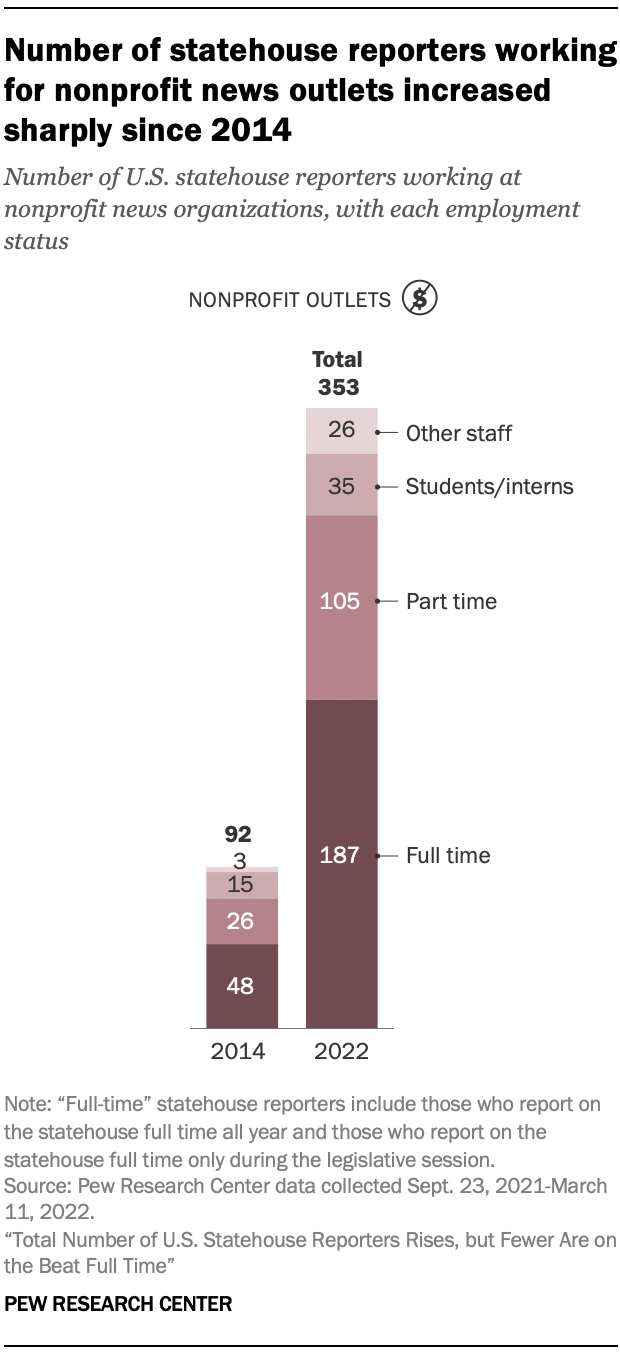

Nonprofit news organizations have grown in the past years, in many cases replacing newsroom losses in the newspaper industry. Reporters at nonprofits now make up the largest portion of the entire group of statehouse reporters in 10 states, and the second largest in 17 states.

Nonprofit statehouse employees now account for the second-largest portion of all statehouse reporters, more than tripling from a total of 92 reporters in 2014 to 353 in 2022. About half (187) of these reporters are covering state government full time, while 105 reporters do so part time. The rest are either students/interns or other supporting staff.

Much of this growth is due to new nonprofit outlets that cover the statehouse. The study identified 59 nonprofit outlets that had at least one statehouse reporter in 2022, either full time or part time, and were not included in the 2014 study. Some were launched since 2014 with the express goal of providing more coverage of state politics. States Newsroom, for example, launched in 2017 as a large nonprofit network of outlets and now has 23 affiliate news outlets throughout the country.

“This whole project is based on our belief that when you consider the impact that state government has on people’s lives these days and the small amount of coverage in most places, it just felt like that was the place where we could have the most impact,” said Chris Fitzsimon, founder and publisher at States Newsroom. “There are tons of small papers, medium-size towns or even smaller towns who can’t afford an AP subscription anymore and they don’t have a capitol reporter. We make all of our content available for free. A lot of people carry our coverage.”

Other examples include Spotlight PA, which was launched by the Philadelphia Inquirer, the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette and the (Harrisburg) Patriot-News to provide a central source of investigative journalism on state politics,5 and CalMatters, a nonprofit organization that focuses on California political and policy reporting and describes itself as “founded to fill the gap left by a shrinking press corps.”

Some of these arrangements are similar to how wire services traditionally share content with many individual outlets. Jim Friedlich, executive director of the nonprofit Lenfest Institute for Journalism, a major funder and supporter of Spotlight PA, explained that it distributes its content for free “as a public service” to news outlets around the state, which sign a memorandum of understanding regarding the use and presentation of the content.

“The miracle of Spotlight PA is that there are now, at last count, 79 news partners all over the state,” Friedlich said. “Spotlight is a hybrid – the nimbleness of a nonprofit digital news start-up matched with the benefit of large-scale legacy news partnerships and legacy news distribution.” Addressing the idea of the Spotlight PA model spreading to other states, Friedlich said, “I’ve talked to folks in California and people in Syracuse, New York, most recently in Omaha. There’s a great deal of interest in replicating the model of collaborating between digital startups and trusted legacy brands and distribution.”

Television stations

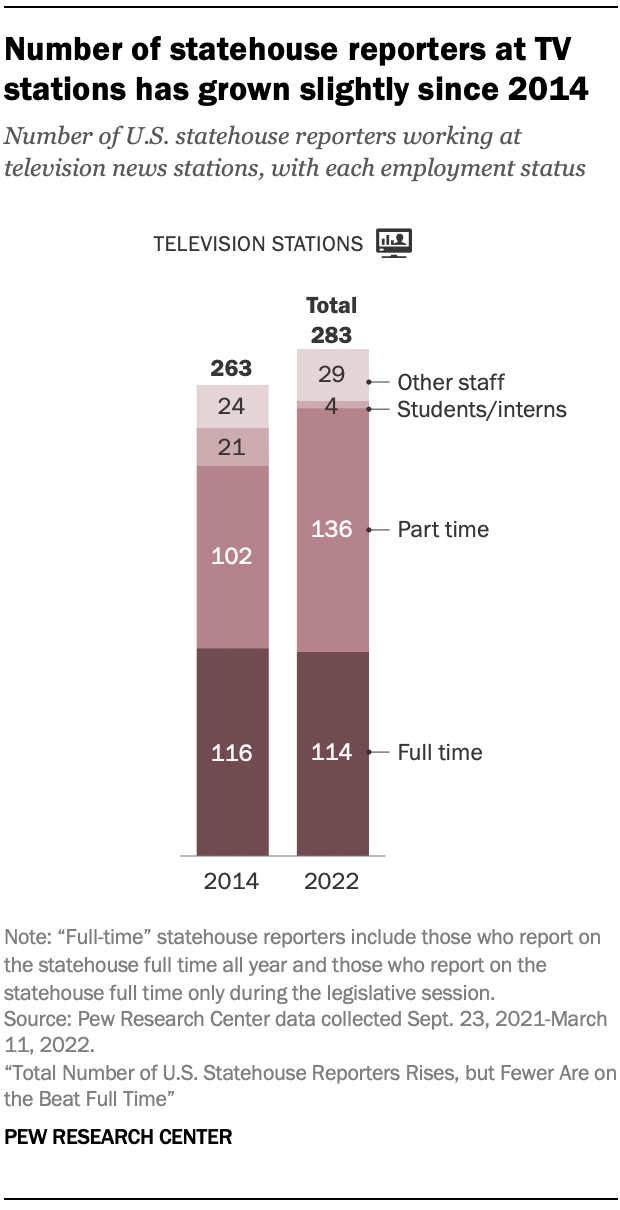

At television stations across the country, 283 journalists provide statehouse coverage, amounting to 16% of all statehouse reporters. This is a slight increase from 2014, when 263 statehouse reporters worked for television stations (though the portion of statehouse reporters from TV stations as a share of all statehouse reporters remained about the same).

The largest group of these reporters (136) cover the statehouse on a part-time basis. These are journalists who often have other assignments and are dispatched to cover the capitol when needed. A smaller group of 114 TV reporters now cover the statehouse full time. Nationwide, 39 states have at least one full-time television reporter covering the statehouse.

Radio stations

Radio reporters constitute a smaller segment of the statehouse press corps (10%) than their television counterparts. That amounts to 178 reporters in all, including 77 who cover the statehouse full time and 75 who do so part time. While the total number of radio statehouse reporters increased by 54 from 2014, the number who cover the statehouse full time shrank by six.

The study identified 85 radio stations assigning statehouse reporters across the country. Most of these are public radio stations, which account for the bulk of the statehouse reporters: Of the 85 radio stations identified, 62 were public radio stations.

Wire services

Newspapers sometimes rely on wire services such as The Associated Press for statehouse reporting rather than employing the personnel themselves. Reporters working for wire services represent 6% of all statehouse reporters, which amounts to 107 reporters in 2022. This is a decline since 2014, when 139 wire reporters covered the statehouse. This decline was mainly seen in the loss of reporters covering the statehouse full time.

“When I started at the Capitol, the Associated Press had a very large presence, but COVID has reduced … that presence,” said Goodland, the chief statehouse reporter at Colorado Politics. “We rarely see the AP people at the Capitol.”

While wire services have a smaller overall presence at statehouses than in the past, the reach of their work still can be much larger than any single news outlet. Wire stories are distributed by an array of local outlets that typically, though not always, pay to be able to carry their content. The AP has the largest footprint (supplied at least in part by the nonprofit Report for America – which is not its own news outlet but instead funds reporters to be stationed in other newsrooms), but other wire services studied here include Forum News Service (which operates in multiple states) and Capitol News Service in Florida.

According to Noreen Gillespie, AP’s deputy managing editor for U.S. news, “AP has made an institutional commitment to maintaining our 50-state footprint and is proud of the ability to strengthen that footprint through our partnership with Report for America. AP covers every statehouse and counts the vote in every state.” She added that the AP’s work is aimed at “helping citizens understand critical decisions made by state governments, how democracy operates, and the forces that threaten free and fair elections.”

Commercial digital-first outlets

In addition to nonprofits, another growing sector of news outlets in recent years includes for-profit organizations that primarily – or in many cases only – publish on the web, whether or not they were initially launched there.6 Those identified here include new locally focused digital outlets like Iowa Starting Line and the Colorado Sun, new state-level entities of larger news websites like Politico, Axios and Bloomberg News, and some outlets that were already a part of the reporting pool in 2014 (such as Civil Beat in Hawaii).7 A small number of digital-first outlets whose self-descriptions or founders have stated editorial viewpoints or policy goals are included in the “ideological” category below because of their clear ideological leanings.

Today, there are more than twice as many statehouse reporters at commercial digital-first outlets than in 2014 (91 vs. 36). This includes an increase at both the full-time level (from 20 in 2014 to 59 in 2022) and the part-time level (from 13 to 23). Reporters at these types of outlets account for the largest segment of all statehouse reporters in two states, and second-largest in five.

Betsy Russell, statehouse reporter with Idaho Press and president of the Idaho Capitol Correspondents Association, noted a transition among digital outlets in that state. Several years ago, “there were a number of digital startups covering the statehouse and it was a whole new thing for us,” Russell said. “Most of those that we had then have gone away, but new ones have come in. And some of them are really solid and have really taken hold.”

University outlets

News outlets based out of colleges and universities provide 5% of all statehouse reporters, 88 in total. This number is a slight decrease from 2014, both in total number and as a share of the statehouse reporting pool overall. Nearly all the reporters at these outlets are students or interns, although some students and interns also report for other outlet types.

These university and college outlets sometimes have a model similar to wires and some nonprofits, in which their reporting is carried by a number of local news outlets. Christopher Drew, director of Louisiana State University’s Manship School News Service, described how they provide important content for outlets that don’t have statehouse reporters. “We’ve built it up to where 89 news sites in Louisiana and Mississippi have now run at least one of our stories,” he said. “They get professional-quality coverage. Then, a lot of these papers are crying for stories and legislative coverage. It’s great for readers and good public service for the school.”

The LSU Manship News Service has about 10 students reporting on the statehouse.

“Those programs are so integral to the current biosphere of statehouse reporting,” said Sarah Gamard, a former state government reporter for the News Journal of Wilmington in Delaware and graduate of the LSU Manship program. “They are so necessary because statehouse reporting is dwindling. … I just think it’s such a good idea for the newspaper industry, because now you’re getting more daily coverage. … It just wouldn’t get covered otherwise, and those [students] are learning.”

Other types of outlets

Employees reporting on statehouses for other types of outlets than the ones mentioned above make up 10% of all of the reporters identified in this study.

Outlets geared toward government insiders make up 4% of the reporters in this study. These outlets, typically subscription-based, focus entirely on the goings-on inside the statehouse and are sometimes oriented around a specific policy issue or the legislative schedule.

Business and law journals and professional or trade publications also employ a small number of reporters covering state capitols (1% of the total reporting pool), typically part time.

Outlets with stated ideological stances also fall into this “other” category. They include outlets that have explicitly stated ideological stances or policy goals either themselves or via their founding organizations. These types of outlets, which tend to publish online only and often have nonprofit status, employ 19 reporters (1% of the total).

U.S. statehouse reporters by state

U.S. statehouse reporters by state