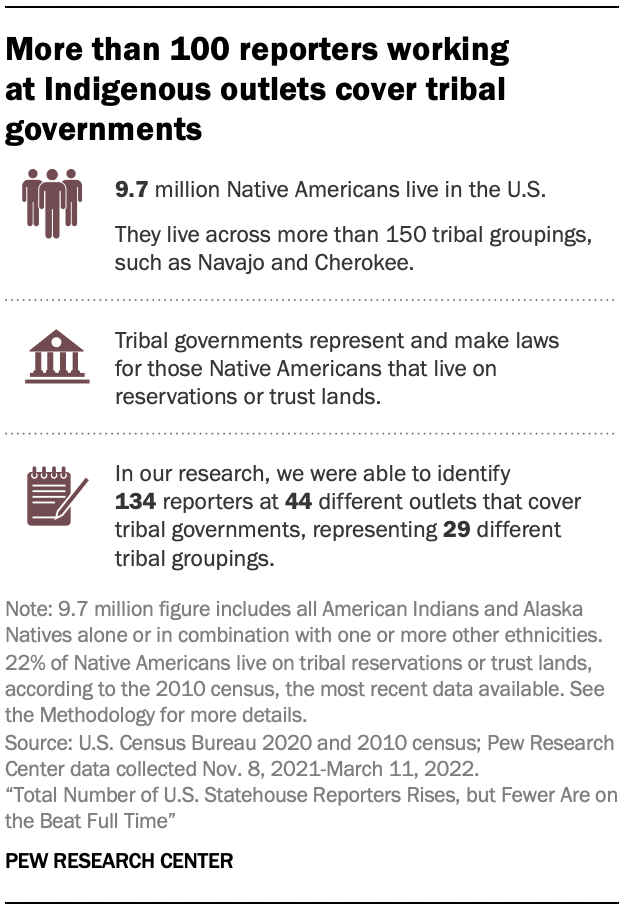

Within the United States, there are 9.7 million Native Americans (as of the 2020 U.S. census).10 About a quarter of Native Americans live on reservations or other trust lands, many of which have their own governments that exist alongside state and federal governments and can enact and enforce laws and regulations.11 As with other government activities, reporters can play a key role in informing citizens about the policy debates and legislative activity in these entities. In a separate analysis, Pew Research Center identified 134 reporters who cover tribal governments for 44 media outlets.

Of these 134 reporters, 78 work for outlets that cover specific tribes, while 56 work at outlets that cover indigenous governments regionally or nationwide instead of focusing on one single tribal government. The reporters identified cover tribal governments that represent 29 of the more than 150 tribal groupings that are tracked by the U.S. Census Bureau. This includes reporters who cover tribal governments connected to three of the five largest tribal groupings – Cherokee, Navajo and Chippewa, each with populations over 150,000, according to the 2010 census.

Because individual tribal nations are largely disparate – both geographically and in their governing structures – accurate data on all of the journalists covering these governments is difficult to gather. The Native American Journalists Association (NAJA) reports having more than 1,000 members, which includes not only journalists but also interested Indigenous and non-Indigenous members of the community. To better understand the number of reporters covering tribal governments and structures behind them, Center analysts reached out to outlets covering Native American communities, and also interviewed eight journalists and experts with experience in this space.

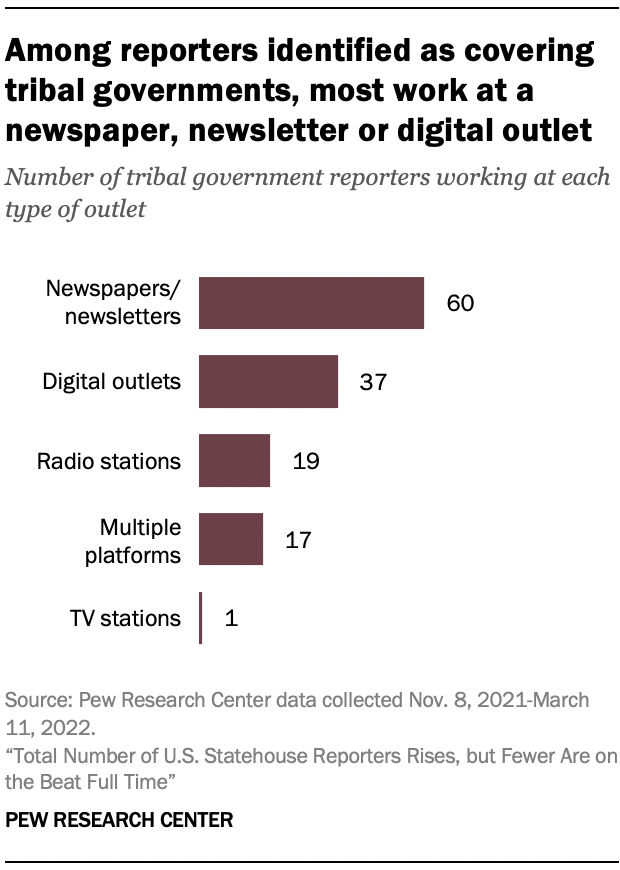

The study found that these 134 journalists covering tribal governments cut across a range of news outlet types. The plurality (60) of these reporters work for either a newspaper or newsletter, while 37 work for digital outlets, 19 work for radio stations, one works for a television station, and 17 work at outlets that cover multiple platforms (such as both a radio station and a newspaper). Additionally, a number of radio stations covering Indigenous issues noted that while they don’t have a specific reporter, they broadcast the audio of their local tribal council meeting on the radio. Of the 37 reporters working for digital outlets, 32 work for Indian Country Today, an outlet that covers Indigenous news nationwide.

Some of these outlets – 18 of the 44 – also have one or more reporters covering the local statehouse. In some cases, the same reporter is assigned to cover both a tribal government and a statehouse – each on a part-time basis.

Financing and ownership structure of Indigenous news outlets

One key difference between the media organizations that cover U.S. statehouses and the Indigenous media organizations that cover Indigenous governments is the relationship between the media organizations and the governments they cover.

The study identified some independently run outlets, but many outlets covering tribal governments are connected in some way with the tribe itself, whether through funding or operations. For example, of the 44 outlets with tribal government reporters identified by researchers, 13 have websites hosted directly on the tribal government website; researchers also identified at least 24 that have some form of stated tribal funding or support. Some outlets are fully run by the tribal government itself.

The financial support provided by tribes can have significant implications for how outlets operate and how much editorial independence they have. Sterling Cosper, membership manager for NAJA and former manager of Mvskoke Media, which serves the Muscogee (Creek) Nation in Oklahoma, did not offer a very bullish assessment of the state of editorial independence among Indigenous outlets covering tribal governments. Many of them, he said, are effectively precluded from doing investigative journalism and reporting aggressively on sensitive topics.

Cosper said the issue of editorial independence “comes back to the funding. If there was more available funding out there, I would say we operate under a public media model.” Additional sources of revenue, he noted, would help these outlets become “more self-sufficient.”

Reflecting on his time at Mvskoke Media, Cosper said the community began questioning the quality of its journalism when an embezzlement conviction of a tribal leader exposed a large difference between the Tulsa World’s coverage and what Mvskoke Media was able to report. According to Cosper, this, along with other scandals afterwards, was a factor in the introduction and passing of the tribe’s first free press law. He resigned from Mvskoke Media in 2018 when the tribe repealed a free press law it had previously enacted.

“I think that maybe five or six tribes that we know of have free press protections. A lot of them are at that codified level. Then you think about all the other tribes,” Cosper said. To illustrate the connection to financial support, he said those in the tribal community opposed to editorial independence say things like: “People are welcome to start their own outlet.”

Paul DeMain, who was managing editor of Wisconsin-based News from Indian Country before it ceased publishing in 2019, said, “I am not aware of any independent Indigenous media covering tribal governments in Wisconsin. … All tribal publications are more attuned to publishing enhanced tribal council news release PR since they are funded by the same tribal government.”

The campaign for press access and independence

Dean Rhodes, the editor of Smoke Signals, which covers the Grand Ronde Tribe community in Oregon, said his news organization is funded by tribal revenue from casino proceeds. In 2016, the tribal council for that community approved an independent tribal press ordinance for Smoke Signals – giving the news outlet editorial independence. But generally, he noted, tribes that fund their media outlets have a good deal of leverage over them.

“I think it’s a very big ask for tribal governments to carve out a newspaper and let them do whatever they want,” Rhodes said. “Very few have done it.”

Another example is KSUT Radio, based in Ignacio, Colorado, home of the Southern Ute Tribe. KSUT was founded in 1976 and became an NPR affiliate in the 1980s, according to Executive Director Tami Graham. The tribe allowed the station to transform into an independent nonprofit and now, “the tribe doesn’t control in any way, our programming or anything,” Graham said. “We do have a lot of in-kind support from the tribe like HR and accounting and things like that. We’re still located on the tribal campus, but we’re an independent nonprofit.”

Once his tribe granted Smoke Signals editorial independence, Rhodes said, their freedom to report increased significantly. “Beforehand, we just knew there were places we couldn’t go and stories we shouldn’t cover if we wanted to keep our jobs,” he explained. Since then, “we have covered stories where we have gotten significant blowback, but we’ve stood up for them. We covered a tribal elder who was convicted of embezzling money from a committee. That would never have happened before.”

Rhodes estimated that there are “five or six Native American newspapers that are able to do what they feel is journalistically appropriate,” adding that “the last time I went to a NAJA conference, we put on a seminar about [press independence], and the biggest question we kept getting was, ‘How do we get our tribe to do that for us?’”

Angel Ellis, the current director of Mvskoke Media, said her operation is funded by the tribe. But, she added, it also derives some supplemental income through a printing business and is looking to apply for some grants. And she described a long, but ultimately successful, campaign to win editorial independence at her organization, a battle that included a long period in exile.

In 2011, she was fired as assistant editor from Mvskoke Media (then MCN Communications) following the organization’s aggressive coverage of a scandal involving a tribal leader. She went to work in the non-Native American media, but she returned to Mvskoke Media as a reporter seven years later, in August 2018. Three months after that, the tribe’s press freedom law was repealed.

Due in part to her advocacy, the tribe agreed to a 2021 referendum to allow the community to decide if it supported press freedom. The measure carried easily, with 76% favoring that independence.

The tribal press reform that followed that vote stipulated that “the tribe would always fund [Mvskoke Media] and they would not interfere with our funding,” Ellis explained. But she also suggested that independence for her organization would best be safeguarded with a more arms-length financial arrangement.

“We want all the freedom in the world,” she said. “What we want to push for is eventually to break off into a 501(c)(3), have the government maybe chip us in some funding once a year” – something much more like the public media model.

Asked if other Indigenous media organizations have asked for advice on how to win editorial independence from the tribal government, Ellis said: “I didn’t think about that after the victory and what that would entail. … It has been very overwhelming to be reached out to by so many people who are wanting to know about what we did and wanting to know how we did it, and what advice we might have. It’s just been insane. It’s a joy, too.”

U.S. statehouse reporters by state

U.S. statehouse reporters by state