Unprecedented national news events, a sharp and sometimes hostile political divide, and polarized news streams created a ripe environment for misinformation and made-up news in 2020. The truth surrounding the two intense, yearlong storylines – the coronavirus pandemic and the presidential election – was often a matter of dispute, whether due to genuine confusion or the intentional distortion of reality.

Pew Research Center’s American News Pathways project revealed consistent differences in what parts of the population – including political partisans and consumers of particular news outlets – heard and believed about the developments involving COVID-19 and the election. For example, news consumers who consistently turned only to outlets with right-leaning audiences were more likely to hear about and believe in certain false or unproven claims. In some cases, the study also showed that made-up news and misinformation have become labels applied to pieces of news and information that do not fit into people’s preferred worldview or narrative – regardless of whether the information was actually made up.

Of course, differences in political party or news diet are not always linked with differences in perceptions of misinformation, nor are they the only factors that have an impact. As explained in Chapter 2, using Donald Trump himself as a news source connects closely to beliefs about certain false claims and exposure to misinformation. So, too, does the reliance on social media as the primary pathway to one’s news, as discussed in Chapter 4.

The Pathways project, then, revealed the degree to which the spread of misinformation is pervasive, but not uniform. Americans’ exposure to – and belief in – misinformation differs by both the specific news outlets and more general pathways they rely on most. Certain types of misinformation emerge more or less strongly within each of these. For example, Americans who rely most on social media for their news (and who also pay less attention to news generally and are less knowledgeable about it) get exposed to different misinformation threads than those who turn only to sources with right-leaning audiences, or to Trump. Both of these latter groups are also more ideologically united and pay very close attention to news.

Takeaway #1: Most Americans said they saw made-up news and expressed concern about it

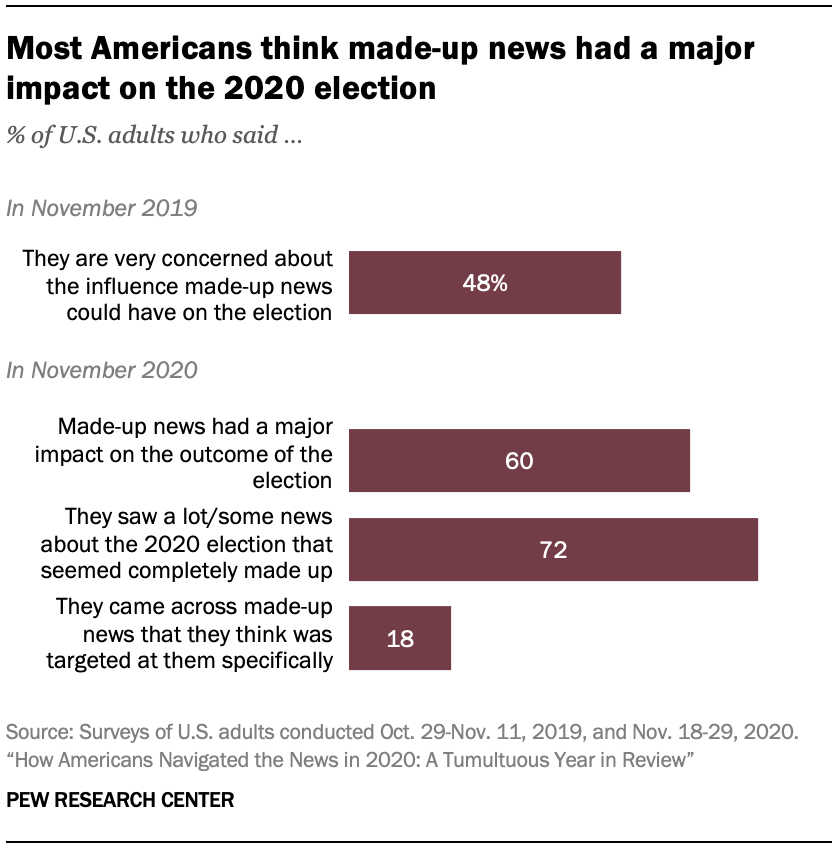

Even a year before the 2020 election, in November 2019, the vast majority of Americans said they were either “very” (48%) or “somewhat” (34%) concerned about the impact made-up news could have on the election. This concern cut across party lines, with almost identical shares of Democrats (including independents who lean toward the Democratic Party) and Republicans (including GOP leaners) expressing these views. But on both sides of the aisle, people were far more concerned that made-up news would be targeted at members of their own party rather than the other party.

Even a year before the 2020 election, in November 2019, the vast majority of Americans said they were either “very” (48%) or “somewhat” (34%) concerned about the impact made-up news could have on the election. This concern cut across party lines, with almost identical shares of Democrats (including independents who lean toward the Democratic Party) and Republicans (including GOP leaners) expressing these views. But on both sides of the aisle, people were far more concerned that made-up news would be targeted at members of their own party rather than the other party.

A year later, in the weeks following the election, Americans said these fears were borne out: 60% of U.S. adults overall said they felt made-up news had a major impact on the outcome of the election, and an additional 26% said it had a minor impact. Republicans were more likely than Democrats to say it had a major impact (69% vs. 54%). In addition, nearly three-quarters of U.S. adults overall (72%) said they had come across at least “some” election news that seemed completely made up, though far fewer – 18% – felt the made-up news they saw was aimed directly at them.

During the year, many Americans also felt exposed to made-up news related to the coronavirus pandemic, a phenomenon that grew over time. As of mid-March 2020, 48% of Americans said they had seen at least some news related to COVID-19 that seemed completely made up. By mid-April, that figure had risen to 64%.

Overall, older Americans, those who paid more attention to news and those who showed higher levels of knowledge on a range of core political questions expressed greater concern about the impact of made-up news. Republicans also expressed more concern and said it’s harder to identify what is true when it comes to COVID-19 news. Meanwhile, those who relied most on social media for political news tended to express less concern about made-up news.

Takeaway #2: What Americans categorized as made-up news varied widely – and often aligned with partisan views

Especially in America’s polarized political environment, just because people say that something seemed made up doesn’t mean it was. Without a doubt, many Americans who report encountering made-up news actually did, while others likely came across real, fact-based news that did not fit into their perceptions of what is true. Indeed, open-ended survey responses show that people’s examples of made-up news they saw run the gamut – often connected with partisan divides about reality.

Especially in America’s polarized political environment, just because people say that something seemed made up doesn’t mean it was. Without a doubt, many Americans who report encountering made-up news actually did, while others likely came across real, fact-based news that did not fit into their perceptions of what is true. Indeed, open-ended survey responses show that people’s examples of made-up news they saw run the gamut – often connected with partisan divides about reality.

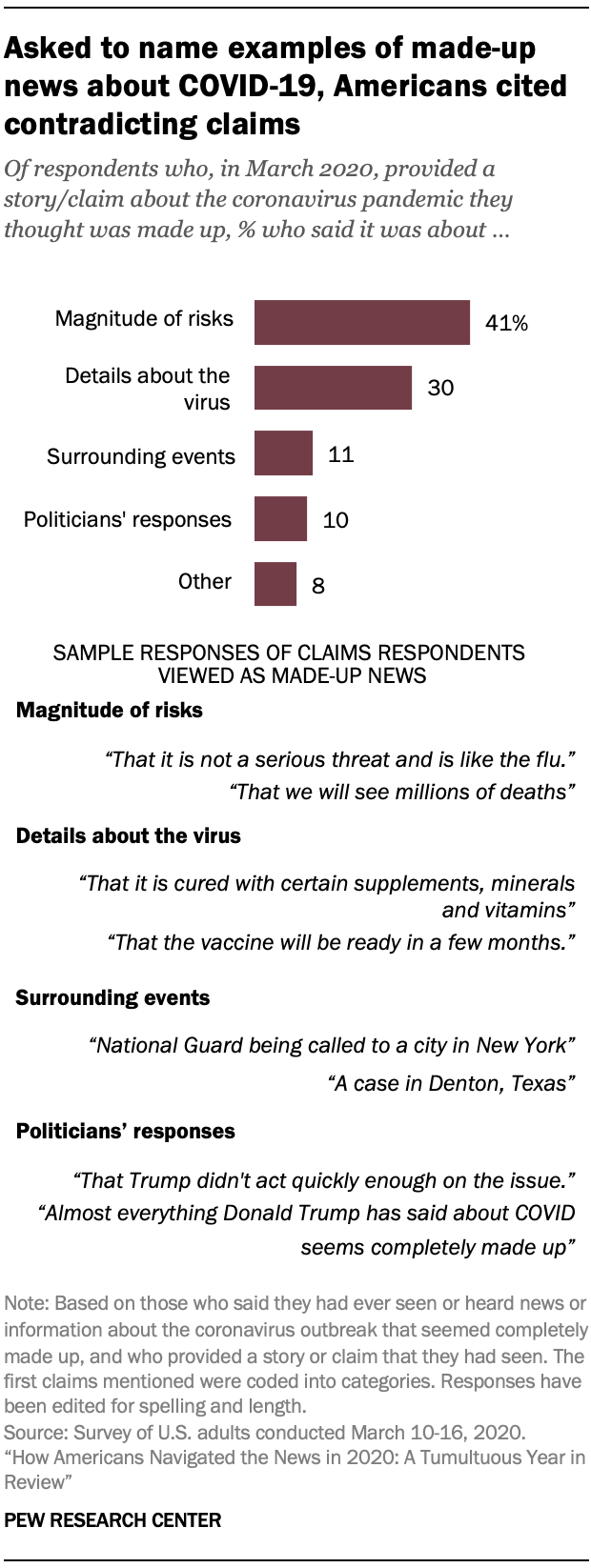

In March of 2020, after asking whether people had come across made-up news related to COVID-19, the American News Pathways project asked respondents to write in an example of something they came across that was made up. The responses were revealing, and sometimes contradictory: Roughly four-in-ten (41%) among those who provided an example named something related to the level of risk associated with the outbreak. Within this category, 22% said the “made-up” information falsely elevated the risks (Republicans were more likely to say this than Democrats), and 15% felt the made-up information was falsely downplaying the risks (Democrats were more likely to give these examples).

Respondents’ examples of made-up news that exaggerated the severity of the pandemic included such claims as numbers of COVID-19 deaths that seemed higher than possible, and the idea that risks had been overplayed by investors so they could make “gobs of money.” Some of these respondents said it was the media overhyping the risk, including one respondent who objected to a front-page newspaper photo designed to equate the coronavirus with the 1918 Spanish flu.

On the flip side, respondents’ examples of made-up news that underplayed COVID-19’s significance included references to statements made by Trump or his administration, including the then-president predicting an early end to the crisis and suggesting that the number of cases in the U.S. would remain low.

Three-in-ten respondents pointed to details about the virus itself. This included some truly made-up claims, such as that it could be “cured with certain supplements, minerals and vitamins,” and others that were perceived by respondents as made up but were not. For example, some respondents listed “wearing a mask for the general public” as an example of a misleading claim. Finally, 10% identified purely political statements as examples of misinformation, such as “That Trump didn’t act quickly enough,” or, by contrast, that “Almost everything Donald Trump has said” about the coronavirus has constituted made-up news.

Takeaway #3: While political divides were a big part of the equation, news diet within party has been a consistent factor in what Americans believe, whether true or untrue

In addition to wholly made-up claims, another finding to emerge from the Pathways project was the degree to which news diet also plays into the storylines – both true and untrue – that people get exposed to, how that feeds into perceptions about those events and, ultimately, different views of reality.

This phenomenon appears more strongly among Republicans than among Democrats, in large part due to the smaller mix of outlets Republicans tend to rely on – and within that, the outsize role of Fox News. (This is in addition to differences in perceptions and beliefs between Republicans who relied on Trump for news and those who didn’t, written about in Chapter 2.)

Trump’s first impeachment

Consider one of the first news topics covered by the project: the 2019 impeachment of Donald Trump, which involved Trump’s behavior and motives in withholding military aid to Ukraine, as well as actions there by Democratic presidential candidate Joe Biden (whom Trump had asked Ukraine’s government to investigate).

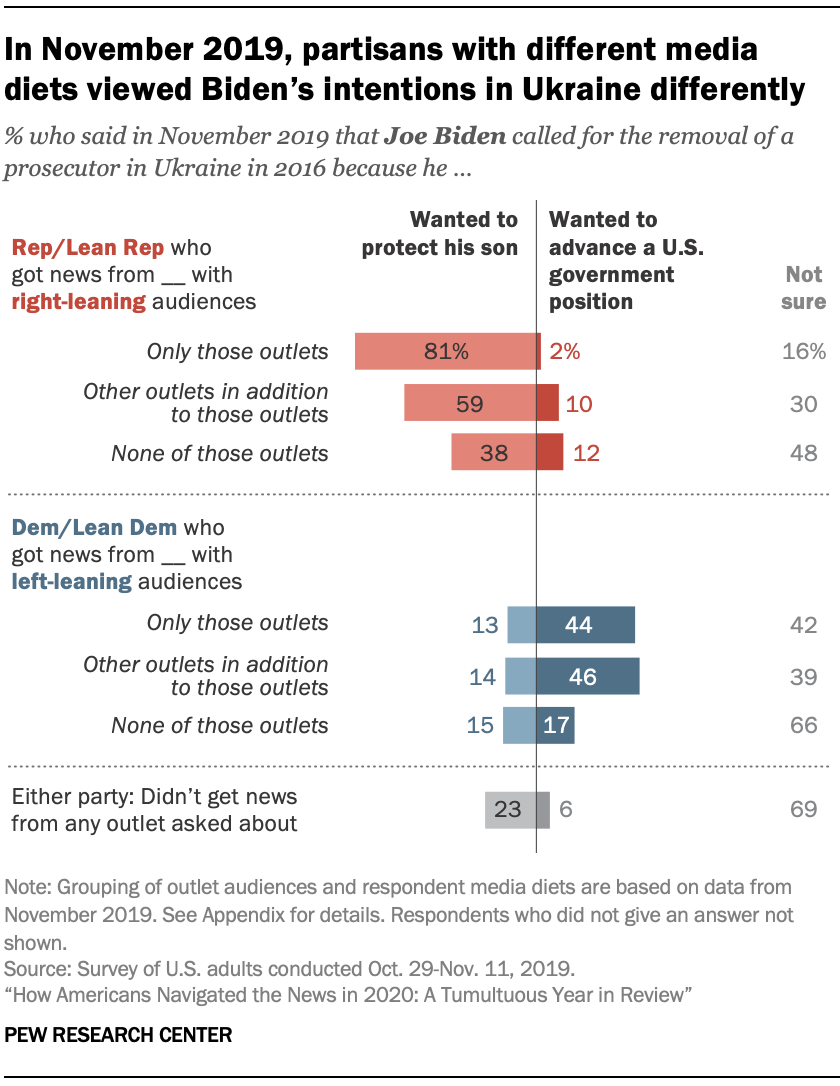

A Pathways survey conducted in November 2019 found that Americans’ sense of the impeachment story connected closely with where they got their news. For instance, about half (52%) of Republicans who, among 30 outlets asked about in that survey, got political news only from outlets with right-leaning audiences had heard a lot about Biden’s efforts to remove a prosecutor in Ukraine in 2016. That is more than double the percentage of Democrats who got news only from outlets with left-leaning audiences (20%) who heard a lot. The gap is similar on Biden’s son (Hunter Biden) work with a Ukraine-based natural gas company: 64% of these Republicans had heard a lot about this, compared with 33% of these Democrats. (Details of the news outlet groupings and audience profiles can be found here.)

These patterns also play out in views about Joe Biden’s motivations. When asked, based on what they had heard in the news, whether they thought Biden called for the prosecutor’s removal in order to advance a U.S. government position to reduce corruption in Ukraine or to protect his son from being investigated, 81% of Republicans who got news only from outlets with right-leaning audiences said he wanted to protect his son. Only 2% of these Republicans thought it was part of a U.S. anti-corruption campaign.

These patterns also play out in views about Joe Biden’s motivations. When asked, based on what they had heard in the news, whether they thought Biden called for the prosecutor’s removal in order to advance a U.S. government position to reduce corruption in Ukraine or to protect his son from being investigated, 81% of Republicans who got news only from outlets with right-leaning audiences said he wanted to protect his son. Only 2% of these Republicans thought it was part of a U.S. anti-corruption campaign.

Democrats who got news only from outlets with left-leaning audiences were much more inclined to attribute Biden’s actions to anti-corruption efforts (44%) than to a desire to protect his son (13%) – though that 44% is nearly matched by 42% who said they were not sure why Biden called for the prosecutor’s removal.

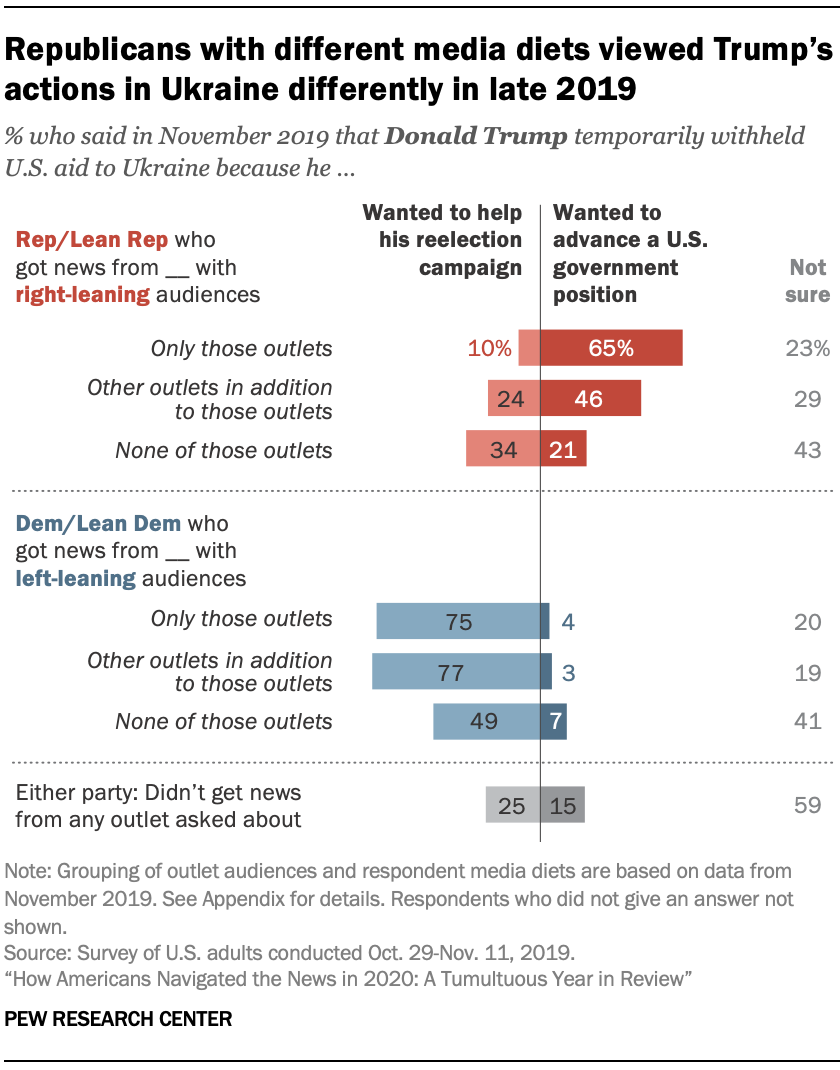

A similar gap is evident when it comes to views about Trump’s role in the Ukraine affair.

A similar gap is evident when it comes to views about Trump’s role in the Ukraine affair.

About two-thirds of Republicans and Republican leaners who got their political news only from media outlets with right-leaning audiences (65%) said he did it to advance a U.S. policy to reduce corruption in Ukraine. Just 10% of these Republicans said Trump withheld the aid to help his reelection campaign (23% said they weren’t sure).

Among Republicans who got political news from a combination of outlet types – some of which have right-leaning audiences and some which have mixed and/or left-leaning audiences – that gap narrows significantly. About half (46%) cited the advancement of U.S. policy, and 24% cited political gain. What’s more, Republicans who did not get news from any sources with right-leaning audiences (but did get news from outlets with mixed and/or left-leaning audiences) were more likely to say it was for political gain than to advance U.S. policy (34% vs. 21%), while 43% of Republicans in this group were not sure why he did it.

Among Democrats and Democratic leaners, those who got political news only on outlets with left-leaning audiences and those who got news from outlets with left-leaning audiences plus others that have mixed and/or right-leaning audiences responded similarly. Roughly three-quarters of Democrats in each of these groups (75% and 77%, respectively) said Trump withheld aid to help his reelection effort, while very small minorities of these Democrats (4% and 3%, respectively) cited reducing corruption as the president’s intent.

The coronavirus pandemic

Several false claims related to the pandemic emerged over the course of the study. Not only did Republicans who turned to Trump for news about the pandemic express higher levels of belief in some of these claims (discussed in Chapter 2), but those who only relied on outlets with right-leaning audiences also stood out in this way (from that same initial group of 30).

Several false claims related to the pandemic emerged over the course of the study. Not only did Republicans who turned to Trump for news about the pandemic express higher levels of belief in some of these claims (discussed in Chapter 2), but those who only relied on outlets with right-leaning audiences also stood out in this way (from that same initial group of 30).

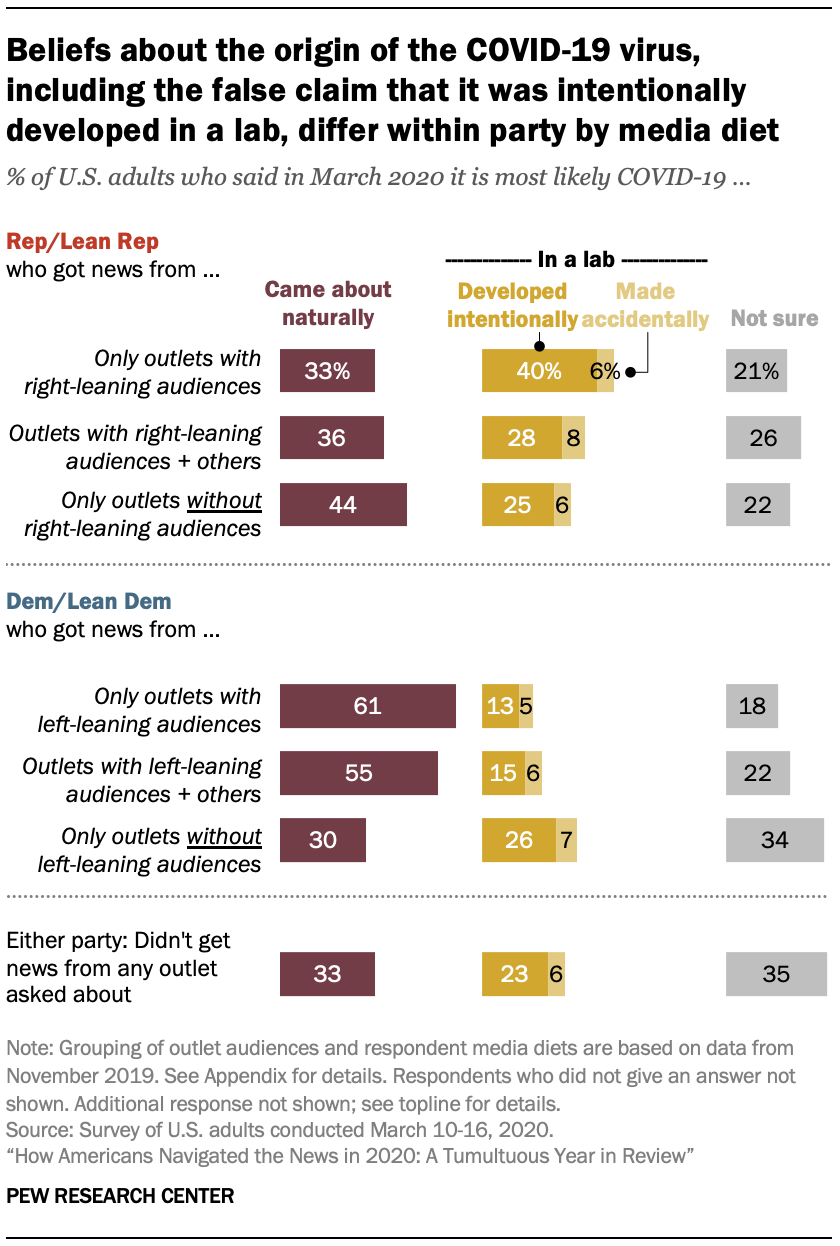

One early claim, made without evidence, was that COVID-19 was created intentionally in a lab. (Scientists have determined that the virus almost certainly came about naturally, but some authorities, while saying it’s unlikely, have not ruled out the possibility that a lab played a role in its release.) When asked in March 2020 what they thought was the most likely way the current strain came about based on what they had seen or heard in the news, 40% of Republicans who only got news from outlets with right-leaning audiences said COVID-19 was most likely created intentionally in a lab, far higher than the 28% of Republicans who got political news from outlets with both right-leaning and mixed audiences and 25% of Republicans who get political news only from outlets without right-leaning audiences.

Among Democrats, those who got political news only from outlets with left-leaning audiences stood out less. They were slightly more likely than Democrats whose news diet included outlets with both left-leaning and non-left-leaning audiences to say the virus strain came about naturally (61% and 55%, respectively). Instead, it was Democrats who didn’t get news from any outlets with left-leaning audiences who stood apart. They were more likely to say COVID-19 was most likely created intentionally in a lab (26%), less likely than other Democrats to say it came about naturally (30%) and more likely to express uncertainty over the virus’ origin (34%).

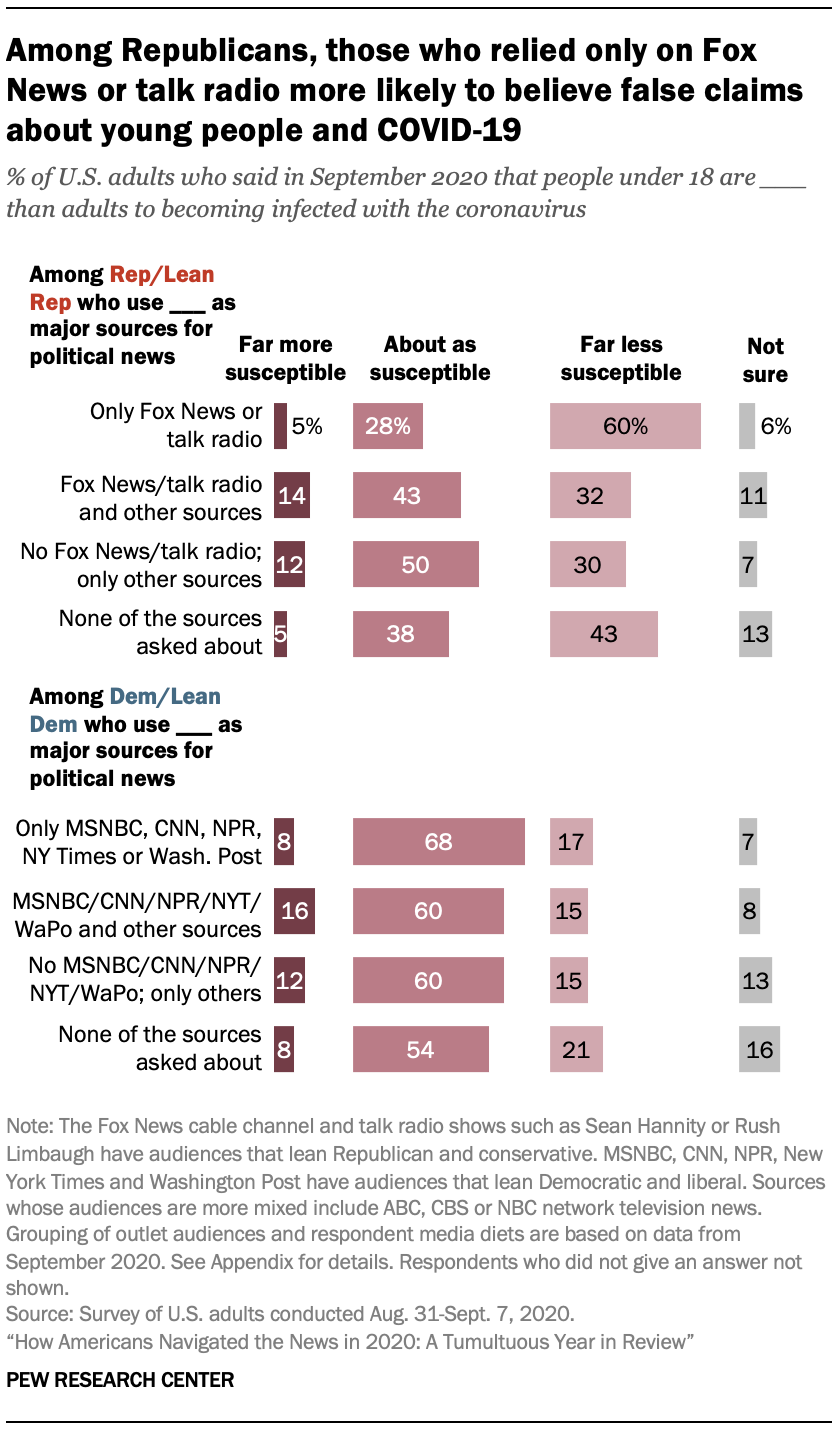

In another area of false claims, Republicans who turned only to outlets with right-leaning audiences (according to whether they used eight sources in September 2020) also stood apart. As of September 2020, they were more likely than other Republicans to believe a much-touted (but false) claim that young people are far less susceptible to catching COVID-19 than older adults. (Young people have much lower rates of severe illness and death from COVID-19, but there is no strong evidence that they are less likely to contract the virus.)

In another area of false claims, Republicans who turned only to outlets with right-leaning audiences (according to whether they used eight sources in September 2020) also stood apart. As of September 2020, they were more likely than other Republicans to believe a much-touted (but false) claim that young people are far less susceptible to catching COVID-19 than older adults. (Young people have much lower rates of severe illness and death from COVID-19, but there is no strong evidence that they are less likely to contract the virus.)

Looking at media diet within party, there were only small differences in responses to this question among Democrats who used different major sources for political news. But among Republicans who used only outlets with right-leaning audiences (in this case among eight asked about), a majority (60%) said that minors under 18 are far less susceptible, compared with far fewer among Republicans who used a mixed media diet (32%) or only major sources without conservative-leaning audiences (30%).

Election 2020

The study also explored the impact of false and unproven claims made prior to Election Day about the potential of voter fraud tied to mail-in ballots (though experts say there is almost no meaningful fraud associated with mail ballots), and then after the fact, whether voter fraud was getting too much or too little attention.

The study also explored the impact of false and unproven claims made prior to Election Day about the potential of voter fraud tied to mail-in ballots (though experts say there is almost no meaningful fraud associated with mail ballots), and then after the fact, whether voter fraud was getting too much or too little attention.

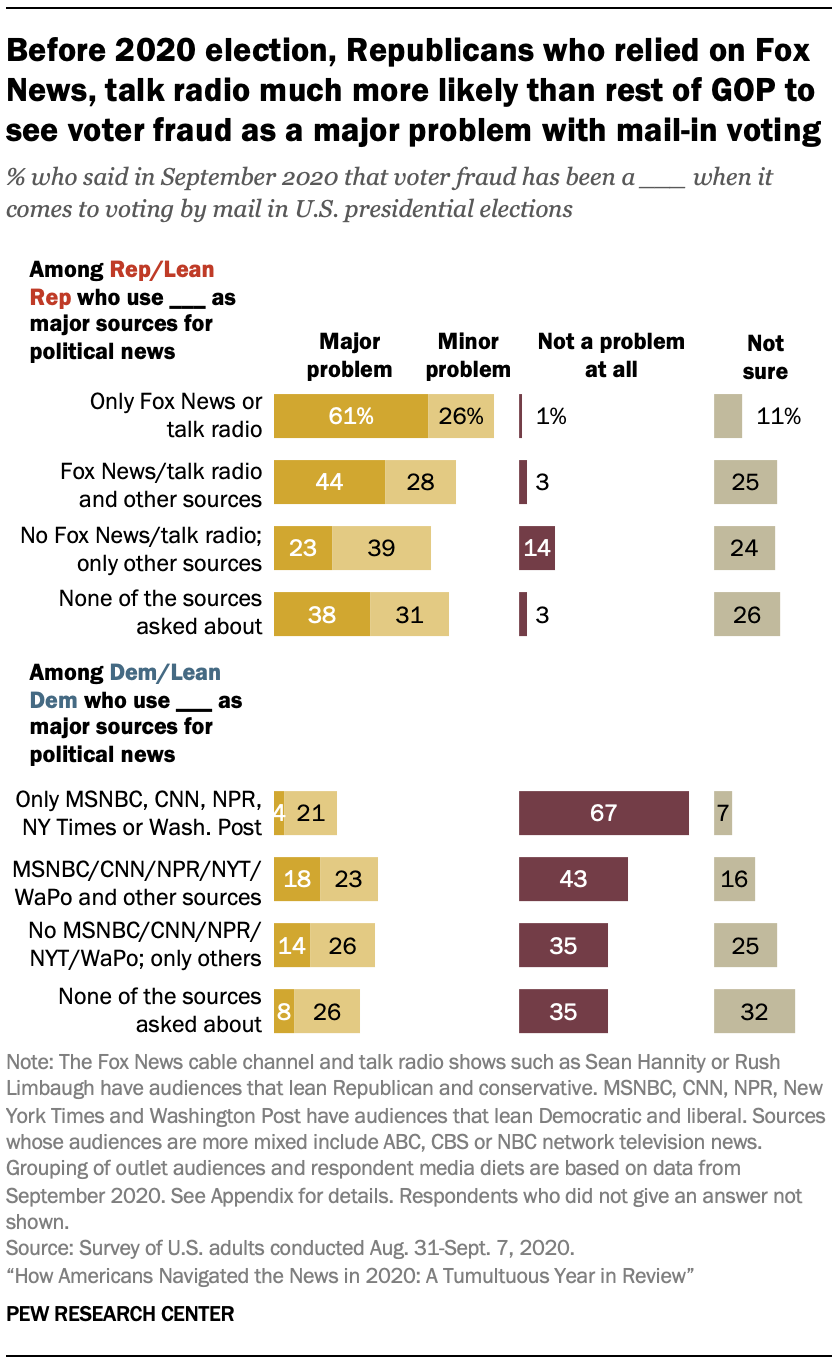

In September, fully 61% of Republicans who only cited Fox News and/or talk radio shows as key news sources said fraud has been a major problem when mail-in ballots are used. That figure drops to 44% for Republicans who cited other outlets alongside Fox News and/or talk radio as major sources, then down to about a quarter (23%) among Republicans who didn’t rely on Fox News or talk radio (but selected at least one of the six other sources mentioned in the survey).

Democrats who cited only outlets with left-leaning audiences as key sources of political news were by far the most likely to say that voter fraud has not been a problem associated with mail-in ballots: 67% said this, compared with 43% of those who relied on some of these sources but also others. Democrats who didn’t rely on any of the outlets with left-leaning audiences (or, in some cases, any of the eight major news sources mentioned in the survey) expressed greater uncertainty on this issue than other Democrats.

Democrats who cited only outlets with left-leaning audiences as key sources of political news were by far the most likely to say that voter fraud has not been a problem associated with mail-in ballots: 67% said this, compared with 43% of those who relied on some of these sources but also others. Democrats who didn’t rely on any of the outlets with left-leaning audiences (or, in some cases, any of the eight major news sources mentioned in the survey) expressed greater uncertainty on this issue than other Democrats.

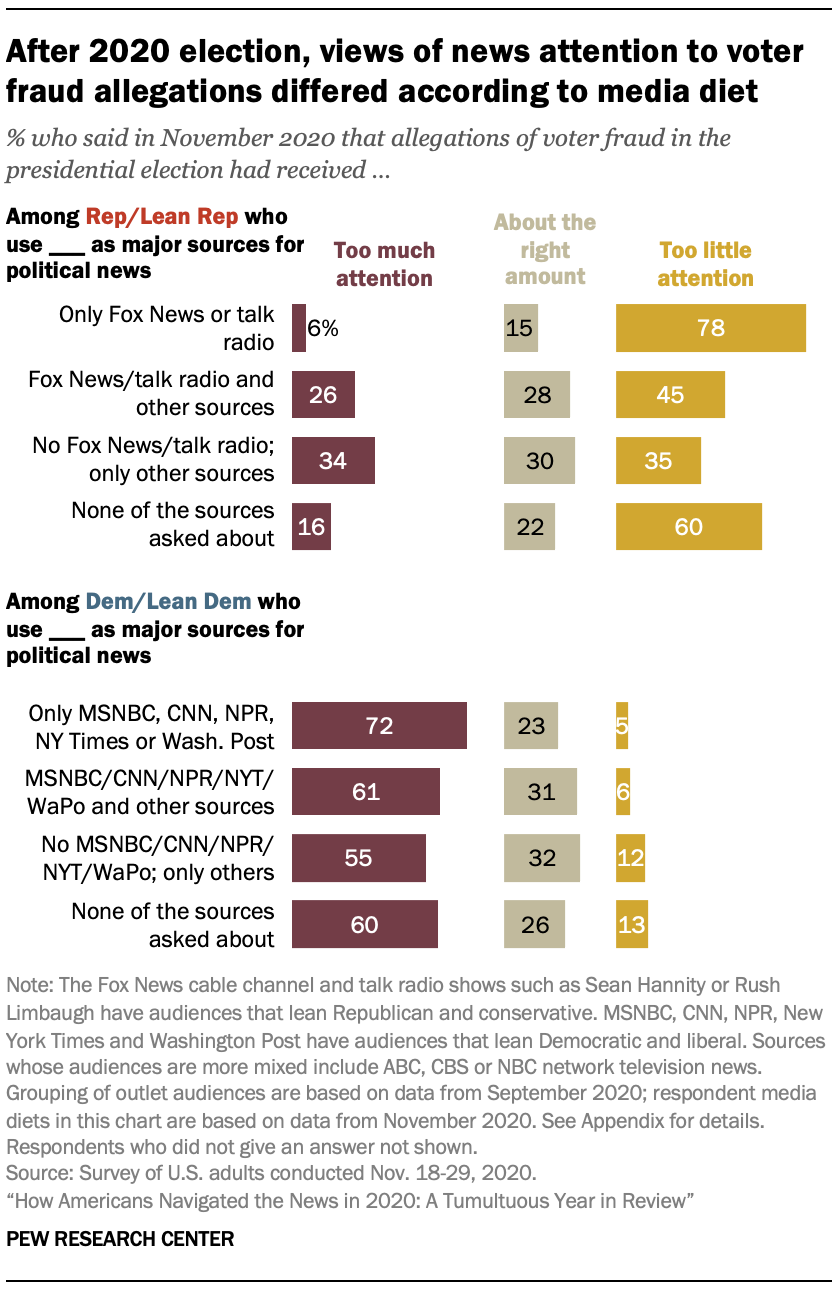

Similarly, after the election, Republicans who turned only to outlets with conservative-leaning audiences were much more likely than those who turned to other outlets to say allegations of voter fraud were getting “too little attention.” Just 6% of Republicans who only used Fox News or talk radio as major sources for post-election news said there had been too much attention paid to the fraud allegations, compared with 78% who said there had been too little attention. In the group that used other sources in addition to Fox News and/or talk radio, 26% said there had been too much attention, while 45% said there had been too little. And Republicans who didn’t rely on Fox News or talk radio at all and only relied on other sources for their post-election news were pretty evenly divided between the two responses.