Beyond the differences in perceptions between partisans – and within parties based on people’s news sources – those who turn to social media as the most common way they get their political news stand out in some ways from those who get news from other pathways (news websites and apps; local, cable, and network TV; radio; and print).

Beyond the differences in perceptions between partisans – and within parties based on people’s news sources – those who turn to social media as the most common way they get their political news stand out in some ways from those who get news from other pathways (news websites and apps; local, cable, and network TV; radio; and print).

Throughout 2020, the Center’s American News Pathways project found that those who primarily got political news on social media tended to follow news – about both the 2020 election and the COVID-19 pandemic – less closely than others. Perhaps related to that fact, this group also was less likely to correctly answer a range of fact-based questions about politics and current events. And in some cases, these social media news consumers were more aware of specific false or unproven stories about the coronavirus and said they had seen more misinformation about the pandemic in general.

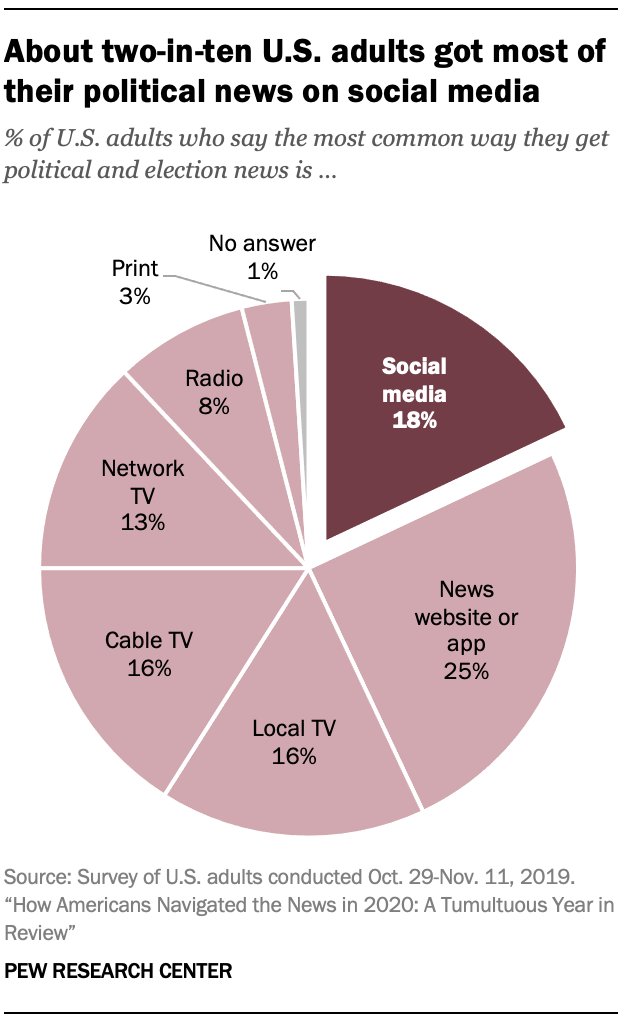

The 18% of U.S. adults who said in late 2019 that social media was the most common way they got political news also differ from other Americans demographically. Most notably, they are the youngest group by a considerable margin – nearly half of the adults who turned mostly to social media are under 30 (48%), compared with 21% of those who turned to news websites or apps, and even fewer of those who said they mostly turned to other platforms like cable television or print. Compared with all other news consumers, U.S. adults who most commonly used social media for news also are less likely to be White (56% are).

Takeaway #1: Social media served as a source of news for many Americans, even as the information there was widely distrusted

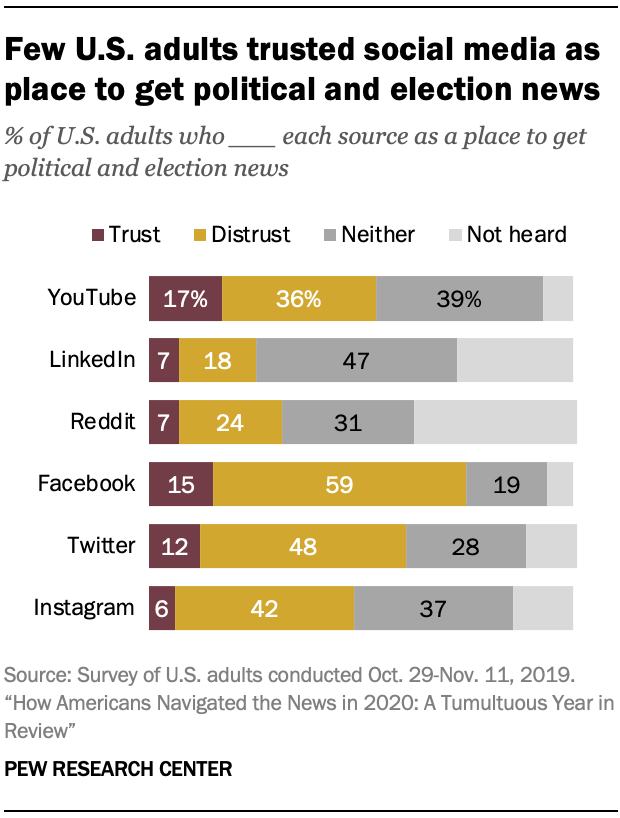

While many Americans get news on social media, the public as a whole largely distrusts these platforms as a source for political news. In November of 2019, both Democrats and Republicans were more likely to express distrust rather than trust in social media sites like Facebook, Twitter and Instagram as sources of political news. For example, among U.S. adults overall, 59% said they distrusted Facebook as a place for political news, compared with just 15% who said they trusted the social networking site.

While many Americans get news on social media, the public as a whole largely distrusts these platforms as a source for political news. In November of 2019, both Democrats and Republicans were more likely to express distrust rather than trust in social media sites like Facebook, Twitter and Instagram as sources of political news. For example, among U.S. adults overall, 59% said they distrusted Facebook as a place for political news, compared with just 15% who said they trusted the social networking site.

The public’s general feeling is that the information they see on social media is likely inaccurate – about six-in-ten social media news consumers think so, according to a survey conducted in September 2020.

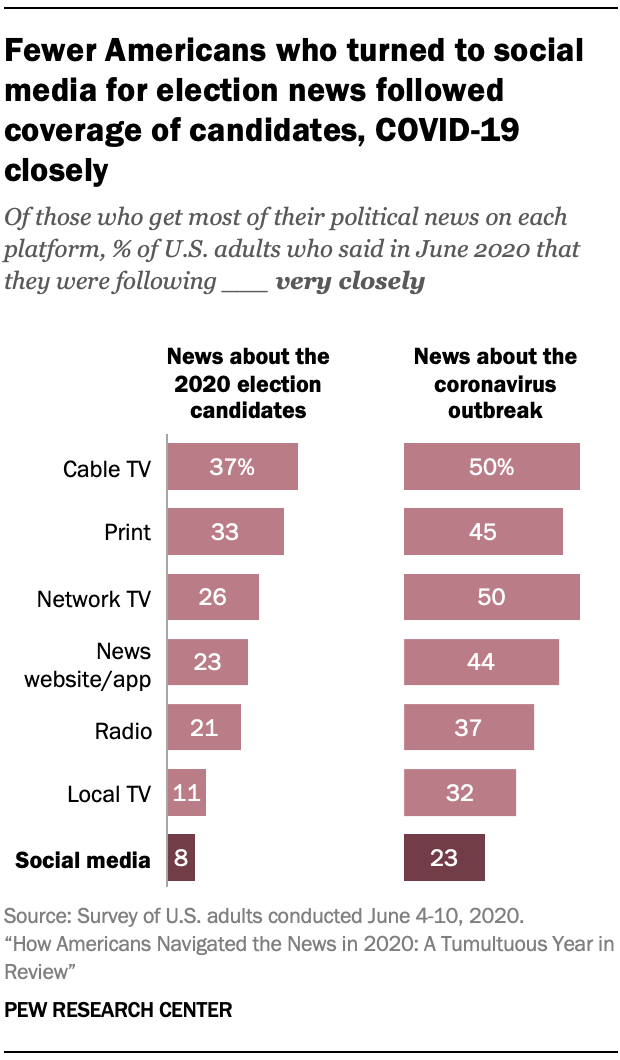

Takeaway #2: Those who turned to social media were less likely to pay attention to multiple types of news

Americans who turn to social media for their news tend to be less engaged with that news than others. They were less likely to say in June 2020, for example, that they had been closely following news about the 2020 election candidates. And those who turned to social media for news also tended to be less aware of a number of specific political storylines early last year, including stories related to Trump’s first impeachment.

Americans who turn to social media for their news tend to be less engaged with that news than others. They were less likely to say in June 2020, for example, that they had been closely following news about the 2020 election candidates. And those who turned to social media for news also tended to be less aware of a number of specific political storylines early last year, including stories related to Trump’s first impeachment.

The same pattern applies to news about the coronavirus pandemic, even as attention to that topic was very high among the general public overall. About a quarter of social media news consumers (23%) said they were following COVID-19 news very closely in June, lower than the shares among those who got news primarily from any other pathway.

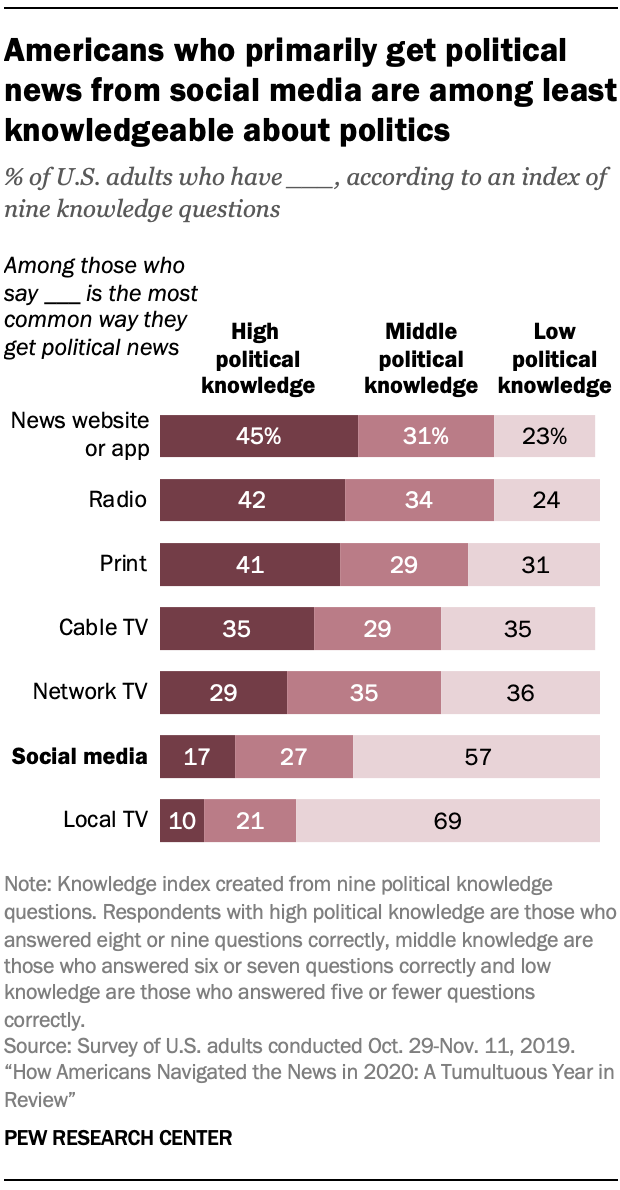

Takeaway #3: Those who relied on social media for news were less likely than most others to be knowledgeable about current events

U.S. adults whose most common way of getting political and election news is social media lag behind Americans who turn to most other sources of news in their knowledge and understanding of national politics, current events and the COVID-19 pandemic.

U.S. adults whose most common way of getting political and election news is social media lag behind Americans who turn to most other sources of news in their knowledge and understanding of national politics, current events and the COVID-19 pandemic.

In November 2019, for instance, Americans who turned to social media for news were among the least likely to correctly answer nine fact-based questions about political knowledge; these nine questions gauged respondents’ knowledge about topics such as trends in unemployment, tariffs, the federal budget deficit and which party supports specific political positions.

Fewer than a quarter (17%) of U.S. adults who relied most on social media for political and election news have high political knowledge, according to this index of knowledge questions.1 Another 27% have middle political knowledge, and a majority (57%) have low political knowledge.

All other groups of news consumers in the study have substantially higher levels of knowledge of national politics, with the exception of Americans who most commonly got their political news from local TV.

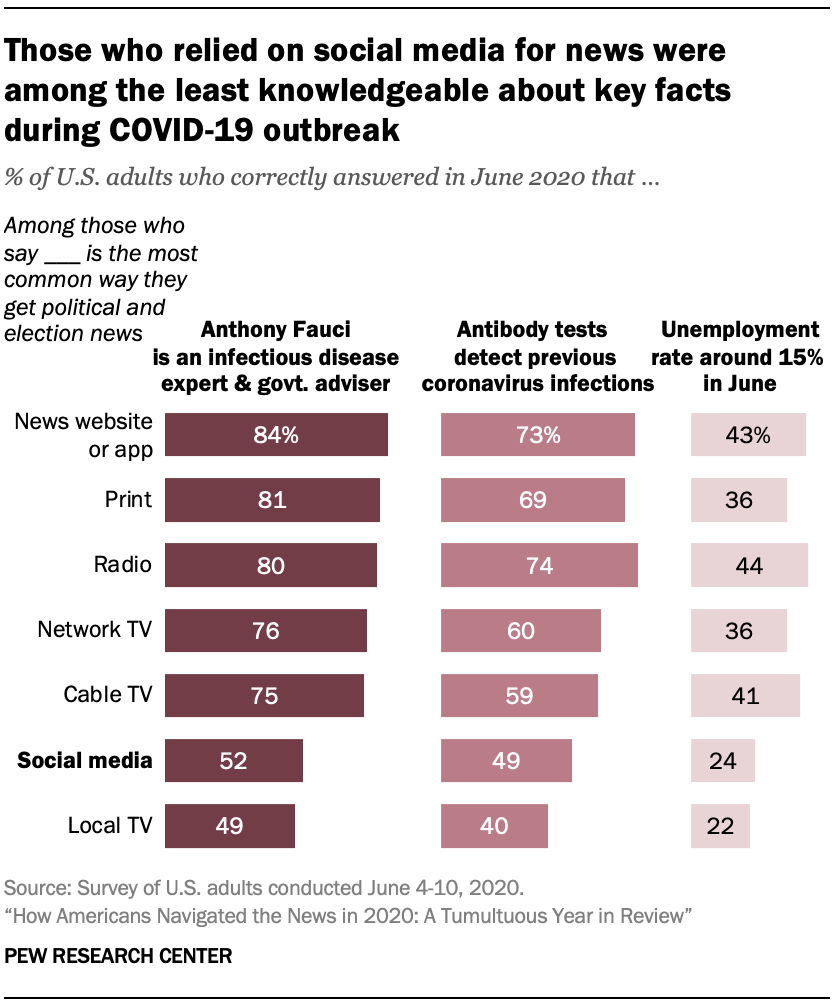

There are similar patterns when it comes to specific questions about the coronavirus pandemic. A June 2020 survey asked U.S. adults what they knew about a few facts relevant to the coronavirus outbreak and its impact on the economy. These questions included one asking respondents to identify Anthony Fauci’s role as an infectious disease expert and government health adviser, another about the purpose of coronavirus antibody tests and a third about the unemployment rate during the pandemic.

There are similar patterns when it comes to specific questions about the coronavirus pandemic. A June 2020 survey asked U.S. adults what they knew about a few facts relevant to the coronavirus outbreak and its impact on the economy. These questions included one asking respondents to identify Anthony Fauci’s role as an infectious disease expert and government health adviser, another about the purpose of coronavirus antibody tests and a third about the unemployment rate during the pandemic.

Americans who relied most on social media for getting political and election news were among the least likely to get these questions right (again, along with local TV news consumers). For example, about half of the social media group (52%) correctly identified Fauci as an infectious disease expert and government health adviser, similar to the share among those who relied on local TV (49%). The other news consumer groups all performed much better on this question; three-quarters or more knew Fauci’s role.

Takeaway #4: Americans who primarily got their political news from social media were more likely to have heard about some unproven claims and theories

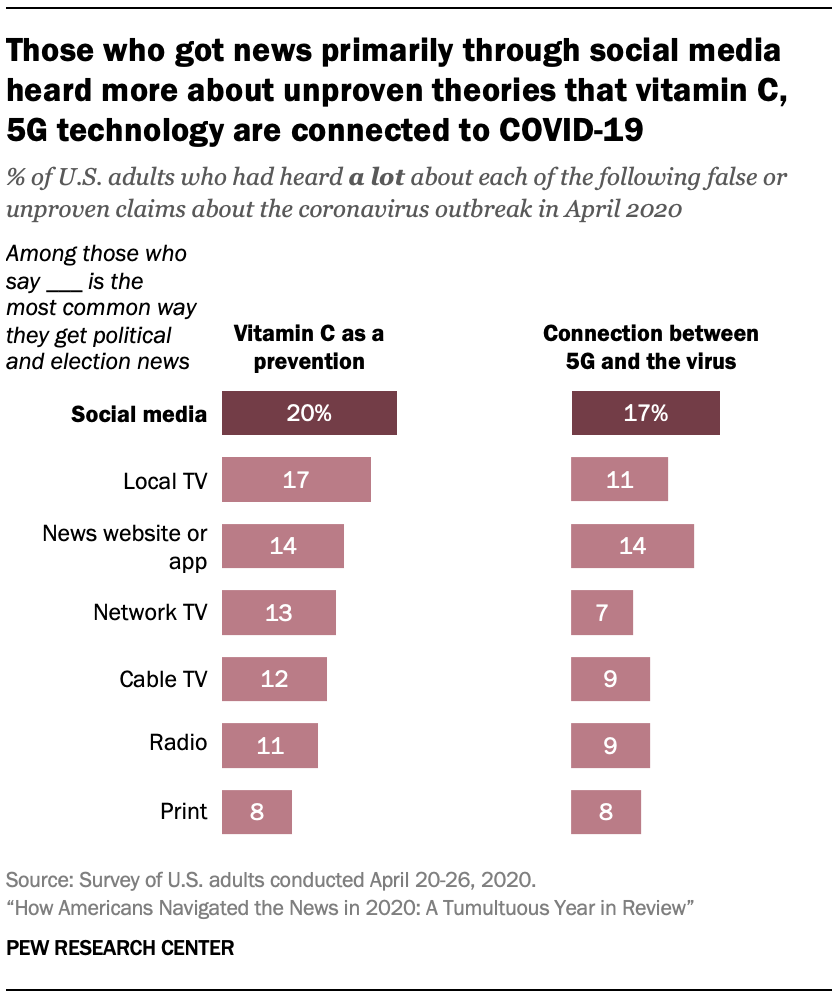

In some cases, false and unproven claims about the coronavirus – such as the idea that there could be a connection between the virus and 5G technology, and the notion that vitamin C could prevent infection – were more likely to reach Americans who got their political news primarily from social media. U.S. adults who said they often turned to social media for coronavirus news specifically also were more likely to say they had heard about the unproven theory that powerful people had intentionally planned the COVID-19 outbreak.

In some cases, false and unproven claims about the coronavirus – such as the idea that there could be a connection between the virus and 5G technology, and the notion that vitamin C could prevent infection – were more likely to reach Americans who got their political news primarily from social media. U.S. adults who said they often turned to social media for coronavirus news specifically also were more likely to say they had heard about the unproven theory that powerful people had intentionally planned the COVID-19 outbreak.

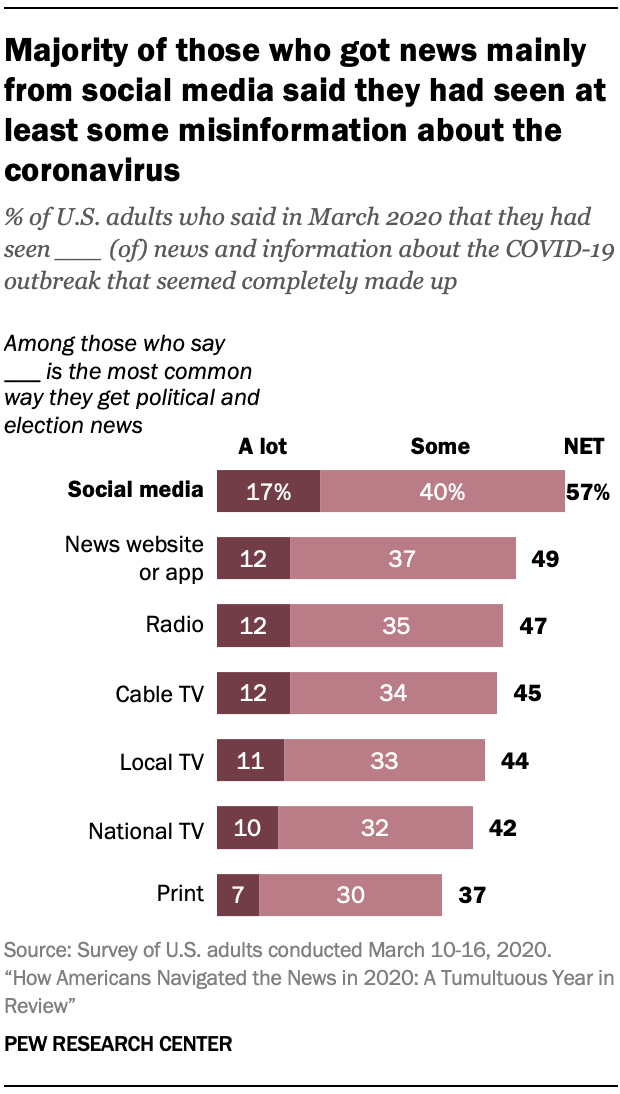

Social media news consumers also were more likely to say that they had seen misinformation about the virus in general – 57% said they had seen at least some, versus 49% or fewer among those who used other platforms as their most common way to get political news.

Social media news consumers also were more likely to say that they had seen misinformation about the virus in general – 57% said they had seen at least some, versus 49% or fewer among those who used other platforms as their most common way to get political news.

Though Americans who turn to social media appear to be more aware of unproven claims and exposed to more misinformation, this doesn’t translate to more concern about the effects made-up news can have. In a November 2019 survey, this group was actually less likely than most others to be concerned about the effects made-up news could have on the 2020 election.