People’s trust in and views about the importance of the news media vary considerably by country. In general, people in Northern European countries – for example, Sweden and Germany – are more likely than people in Southern European countries, including France, to say the news media are very important and that they trust the news media.

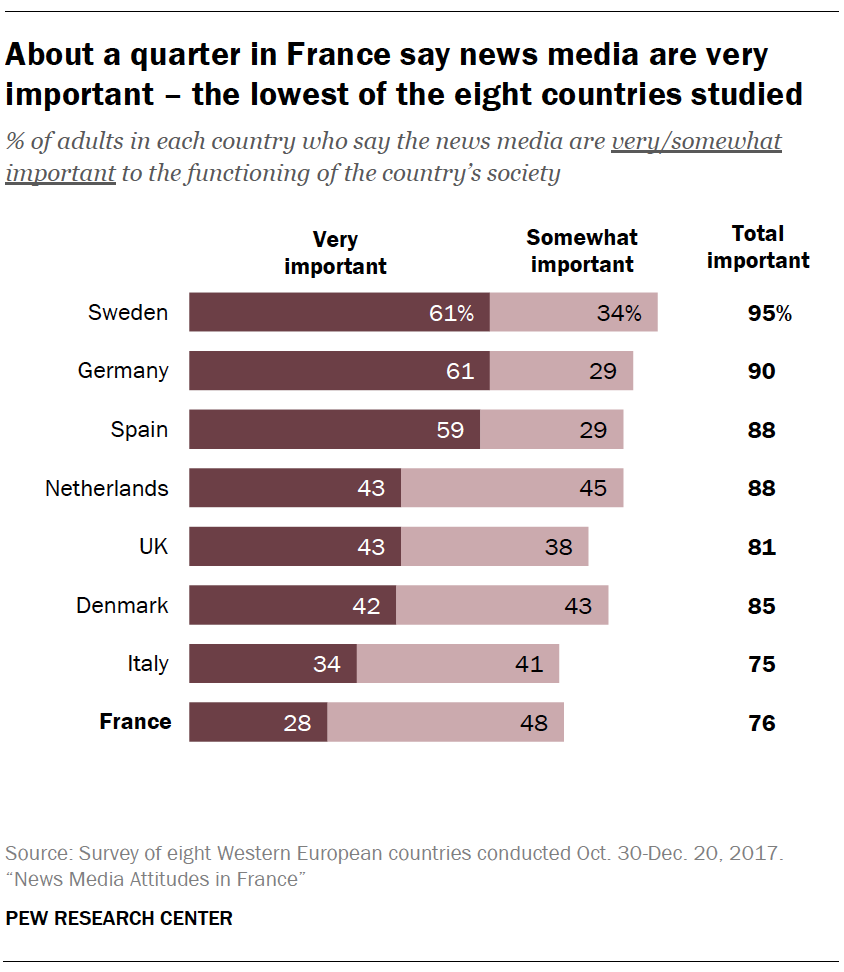

Across the eight European countries studied, three-quarters or more say the news media are at least somewhat important to the functioning of the country’s society. But the share that says the news media’s role is very important varies significantly.

Across the eight European countries studied, three-quarters or more say the news media are at least somewhat important to the functioning of the country’s society. But the share that says the news media’s role is very important varies significantly.

In France, about a quarter of adults (28%) consider the news media very important to society – the lowest of the eight countries surveyed. Another 48% say the news media are somewhat important to society, for a total of 76% who say the news media are at least somewhat important.

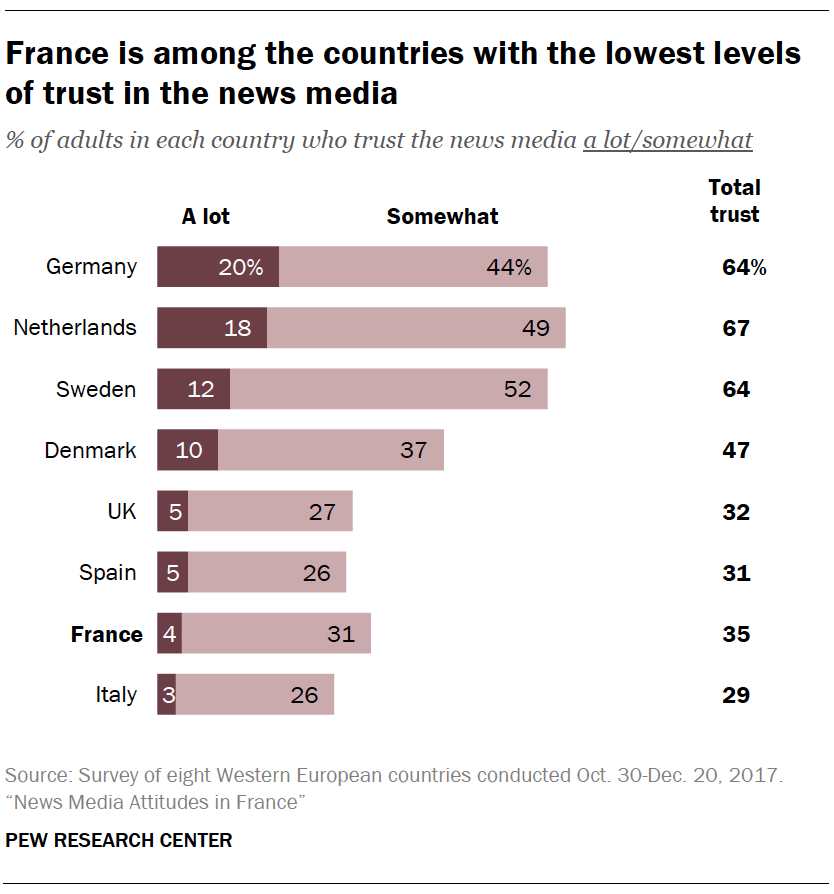

Trust in the news media is lower across Western Europe than people’s sense of the news media’s importance. France has one of the lowest levels of trust of the countries surveyed. About a third of French adults (35%) say they trust the news media at least somewhat, but only 4% say they have a lot of trust. This is similar to trust levels in the UK and in other Southern European countries surveyed; trust levels are substantially higher in the Northern European countries.

Trust in the news media is lower across Western Europe than people’s sense of the news media’s importance. France has one of the lowest levels of trust of the countries surveyed. About a third of French adults (35%) say they trust the news media at least somewhat, but only 4% say they have a lot of trust. This is similar to trust levels in the UK and in other Southern European countries surveyed; trust levels are substantially higher in the Northern European countries.

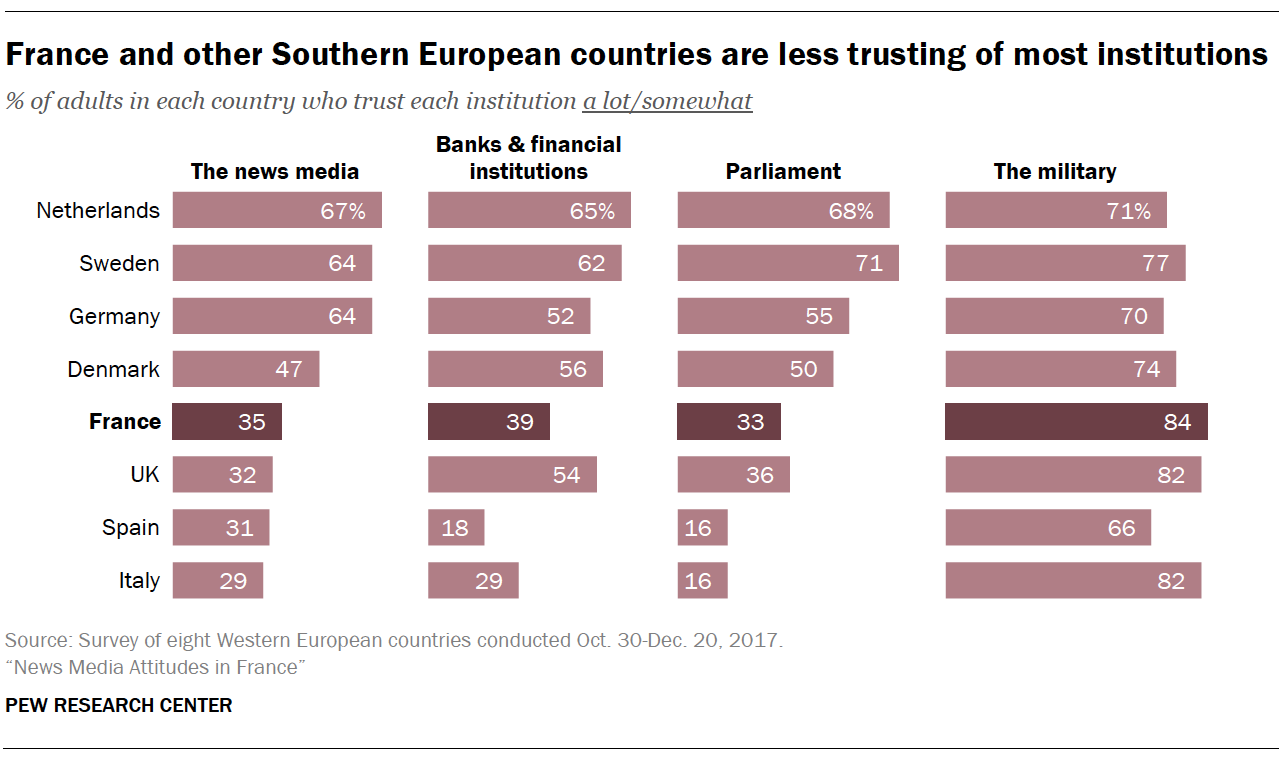

French adults also express lower levels of trust than most other Western Europeans in two other institutions asked about: the national parliament and financial institutions. About four-in-ten or fewer say they trust either institution at least somewhat (33% and 39%, respectively). In contrast, a large majority (84%) say they trust the military at least somewhat.

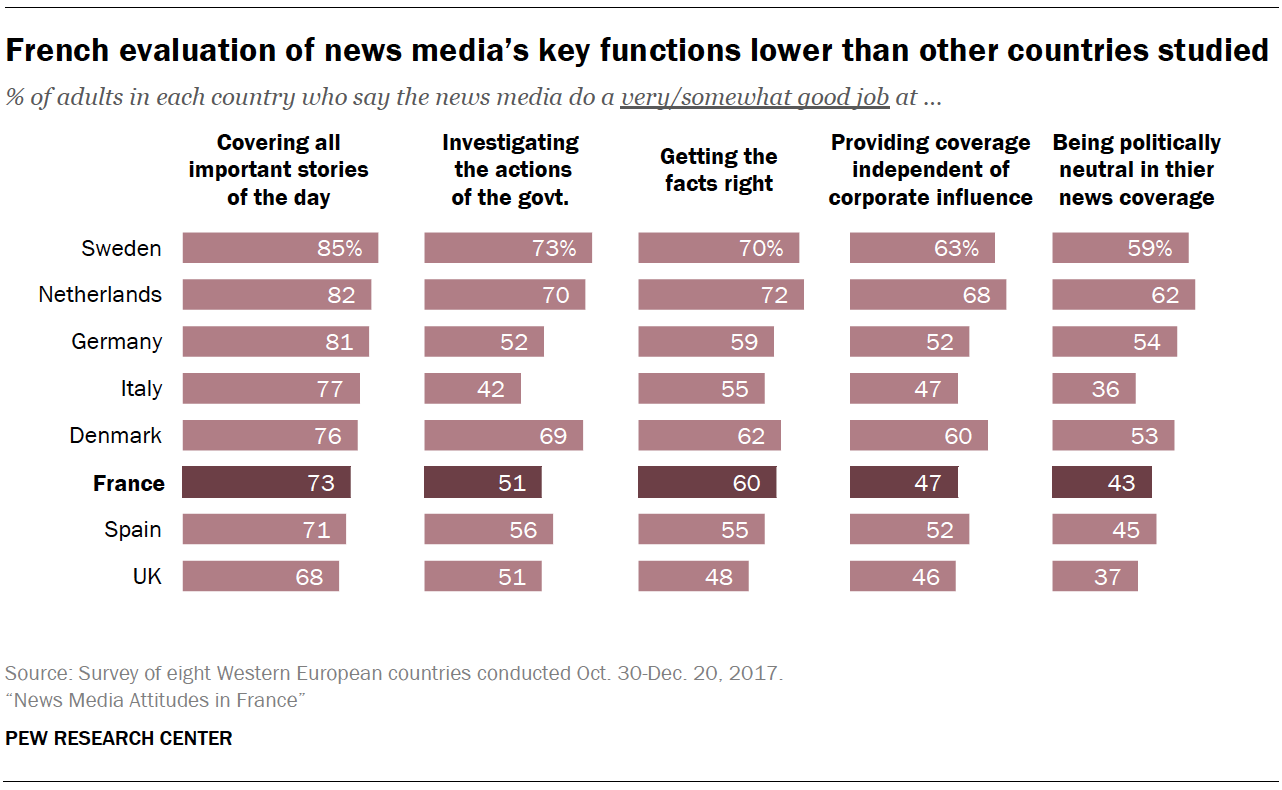

The French give the news media fairly high ratings on several core functions, but still at levels lower than those in Northern European countries. Among five functions asked about, French adults give the news media lowest marks for being politically neutral in their news coverage, with roughly four-in-ten (43%) saying the news media are doing a somewhat or very good job at this. Far more (73%) say the news media do a good job covering the important stories of the day.

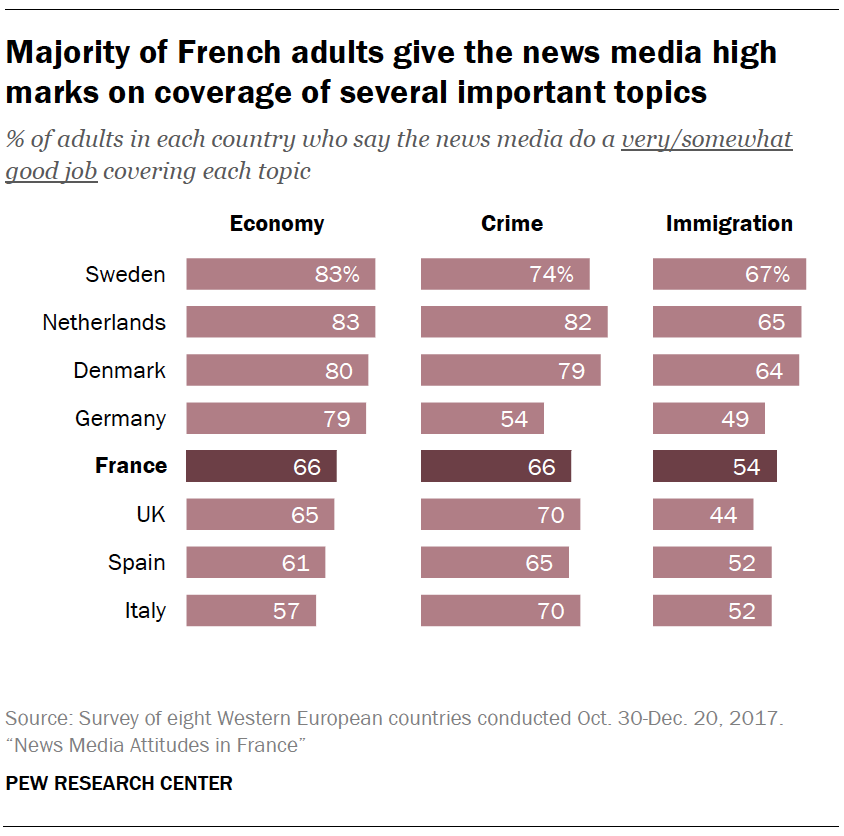

The survey also asked respondents to assess the news media’s coverage of three specific topics – the economy, crime and immigration.

About two-thirds of French adults (66%) say the news media do a somewhat or very good job covering the economy and crime, while a smaller portion (54%) say this about immigration coverage.

About two-thirds of French adults (66%) say the news media do a somewhat or very good job covering the economy and crime, while a smaller portion (54%) say this about immigration coverage.

The French give the news media overall higher marks compared with other Southern European countries, but still lower compared with northern countries. Across all eight countries, immigration coverage received the lowest rating.

How political identities tie into news media attitudes

In most of the countries surveyed, people who hold populist anti-elitist views are less likely than those who don’t hold these views to value and trust the news media. And the differences between these groups are larger than when comparing people on the left and right of the ideological spectrum.

Measuring populist anti-elitist views

Academic studies of populism consistently identify a few key ideas as underlying the concept: The people’s will is the main source of government legitimacy; “the people” and “the elite” are two homogenous and antagonistic groups; and “the people” are good, while “the elite” are corrupt (Stanley, 2011; Akkerman, Mudde, & Zaslove, 2014; Schulz et al., 2017).

The populism measure used throughout this report is based on combining respondents’ answers to two questions: 1) “Ordinary people would do a better job/do no better solving the country’s problems than elected officials,” and 2) “Most elected officials care/don’t care what people like me think.” Both measures are meant to capture the core ideas that the government should reflect the will of “the people” and that “elites” are an antagonistic group that is out of touch with the demands of “the people.” The second measure is a traditional question asked regularly over time on political surveys to measure efficacy and dissatisfaction with government responsiveness. This measure, or ones that are similar, are used by scholars studying populism to capture attitudes about an antagonistic relationship between elites and the people (Stanley, 2011; Spruyt et al., 2016; Schulz et al., 2017).

Those who answered that elected officials don’t care about people like them and who said ordinary people would do a better job solving the country’s problems than elected officials were considered to hold populist anti-elitist views. People who say the reverse – that elected officials care and that ordinary people would do no better – are considered to not hold populist anti-elitist views. Everyone else, including people who refuse to answer one or both questions, is considered to hold mixed views. In France, 40% of adults hold these populist anti-elitist views, 16% do not hold these views, and the remaining 44% hold mixed views.

For more information on this measure, see the Methodology and References of the report “In Western Europe, Public Attitudes Toward News Media More Divided by Populist Views Than Left-Right Ideology,” which uses the same measure, though phrased as “populist views.”

In France, 22% of people with populist anti-elitist views say the news media are very important to society, compared with 42% of those without these views. Regarding trust, 26% of people with these views say they trust the news media at least somewhat, compared with 47% of those without these views.

The sense of media importance in France is also divided by left-right ideology; 39% of those on the left say the news media are very important, compared with 23% of those on the right. There are no differences, however, in trust in the news media between people on the left and right.

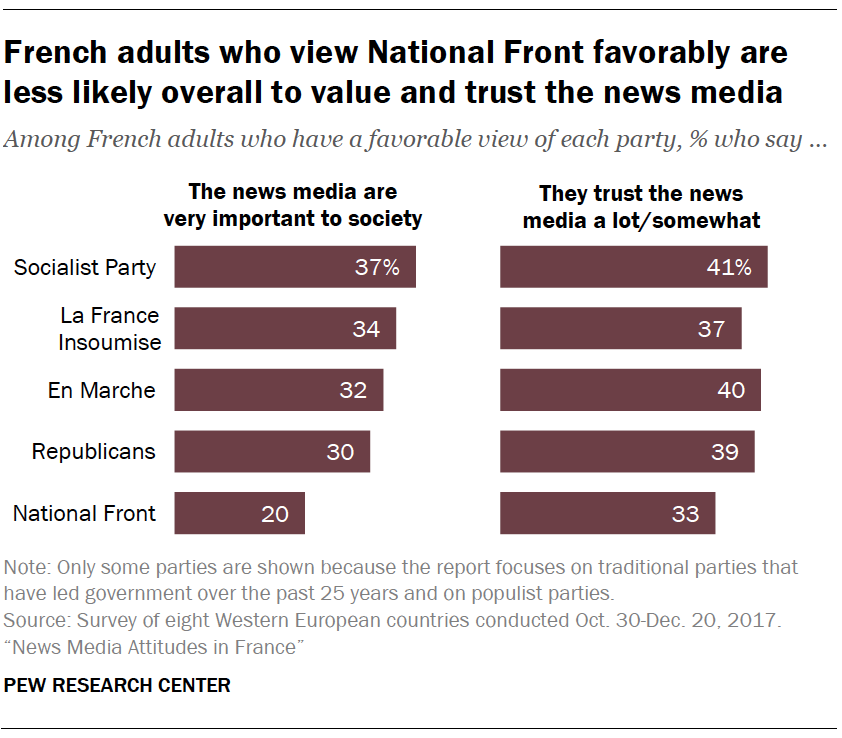

There are differences in news media trust based on political party support, but not nearly at the levels seen around populist anti-elitist views. French adults with a favorable view of the National Front, for example, stand out as the least likely to trust the news media. Among them, a third say they trust the news media at least somewhat, while about four-in-ten who favor one of the other four parties studied say the same.

There are differences in news media trust based on political party support, but not nearly at the levels seen around populist anti-elitist views. French adults with a favorable view of the National Front, for example, stand out as the least likely to trust the news media. Among them, a third say they trust the news media at least somewhat, while about four-in-ten who favor one of the other four parties studied say the same.

Similarly, two-in-ten adults with a favorable view of the National Front say the news media are very important to society, compared with three-in-ten or more of those who have favorable views of other parties.

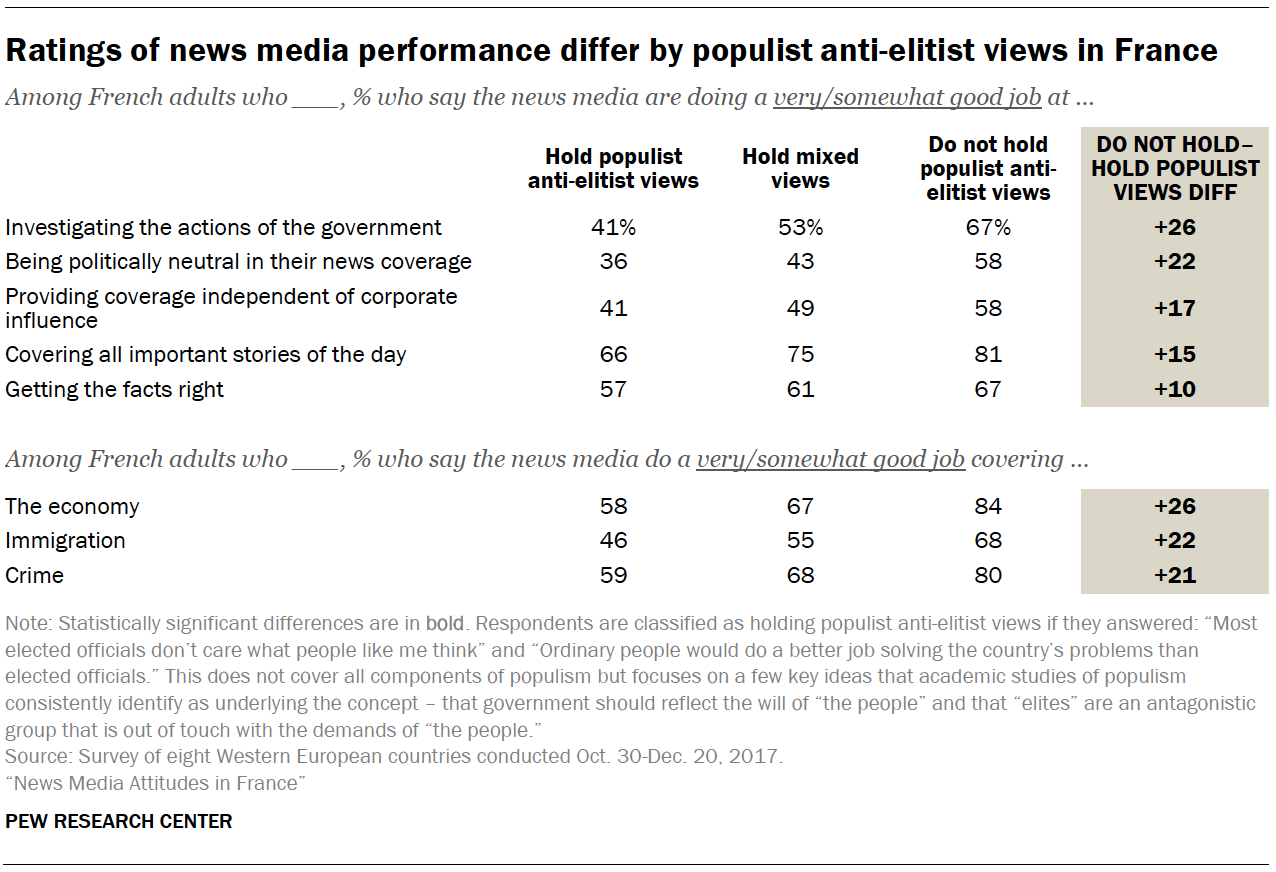

People who hold populist anti-elitist views are less likely to give high ratings on five core functions of the news media. For example, there is a 26-percentage-point difference between those with these populist anti-elitist views and those without on whether the news media are doing a good job at investigating the actions of the government, and a 22-point gap on whether news organizations are politically neutral in how they present the news.

Similarly, those who hold populist anti-elitist views tend to be less satisfied with the news media’s coverage of three topics – by about 20 percentage points or more for each. The largest gap is in the state of the economy: 58% of those who hold populist anti-elitist views say the news media do a somewhat or very good job in its coverage, versus 84% of those who don’t hold these views.

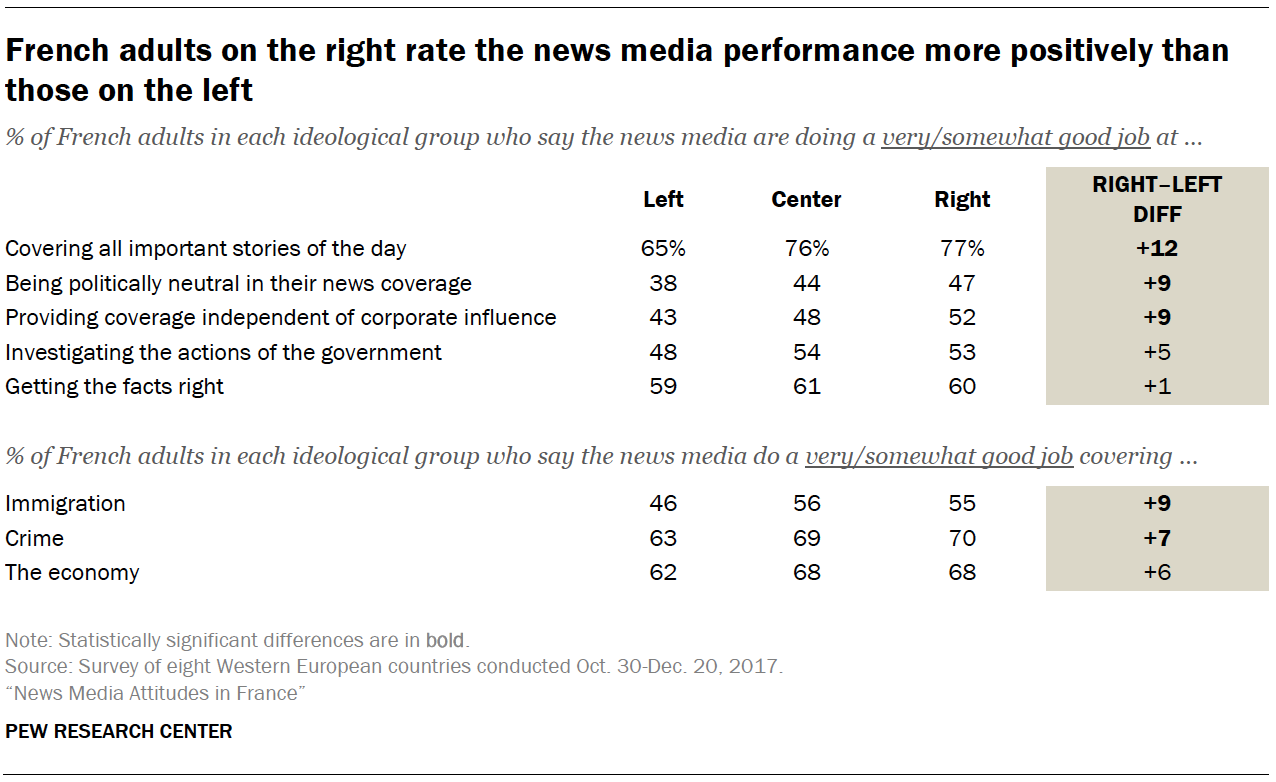

Left-right differences also emerge on these questions, though the differences are not as pronounced as those based along populist anti-elitist views. Overall, French adults on the right are more likely than those on the left to be satisfied with the news media’s performance. For instance, 77% of those on the right say the news media do a somewhat or very good job covering all important stories of the day, while 65% of adults on the left say the same.

Similarly, those on the right are more likely to say the news media do a somewhat or very good job covering immigration and crime – by 9 points and 7 points, respectively. Coverage of the economy, on the other hand, is not significantly divided by left-right ideology.

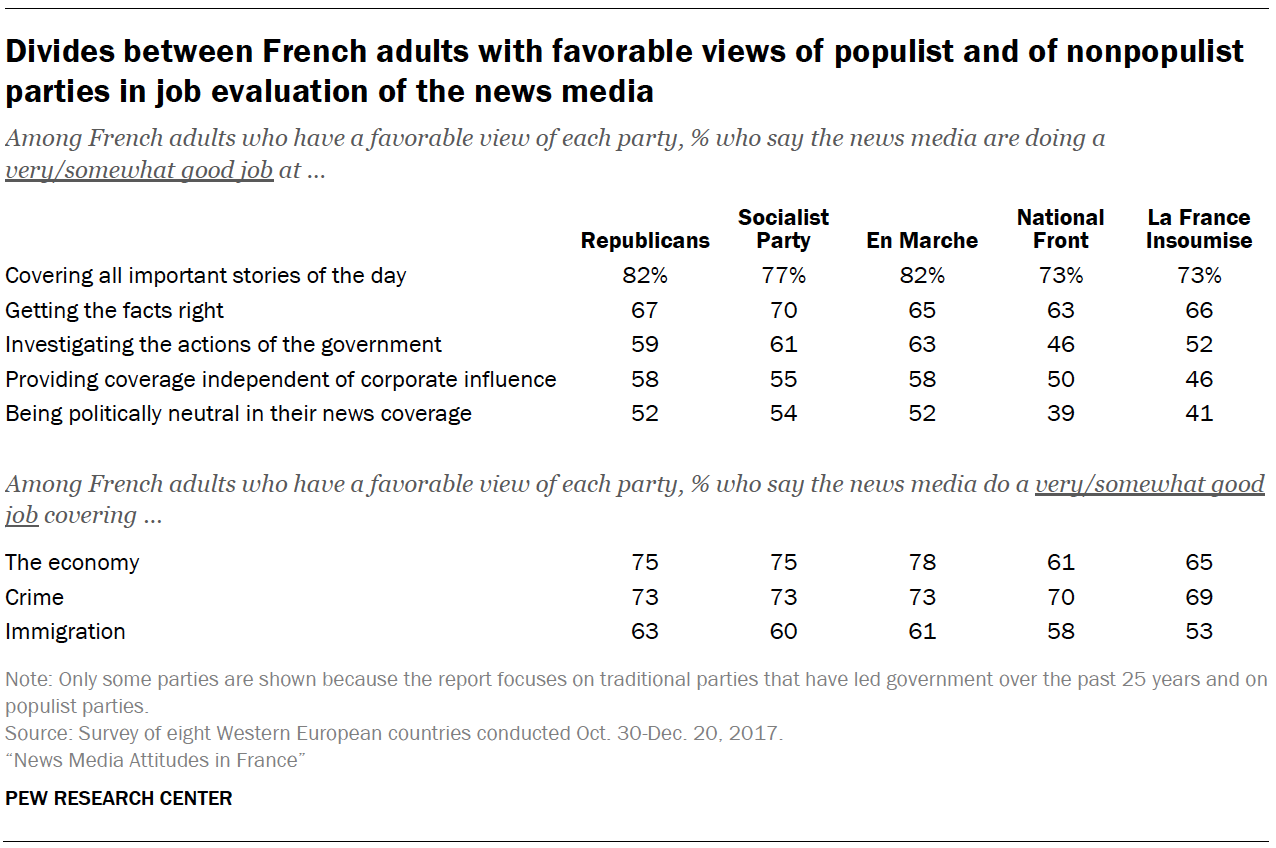

When it comes to party support, those who have a favorable view of either of the two populist parties, the National Front and La France Insoumise, generally give lower ratings of news media performance than those who have favorable views of other parties. For instance, at least half of those in favor of the Socialist Party (54%), Republicans (52%) and En Marche (52%) say the news media do a somewhat or very good job being politically neutral in their coverage, while about four-in-ten adults with a favorable view of La France Insoumise (41%) and the National Front (39%) say the same.

Differences in news media attitudes by social media news use

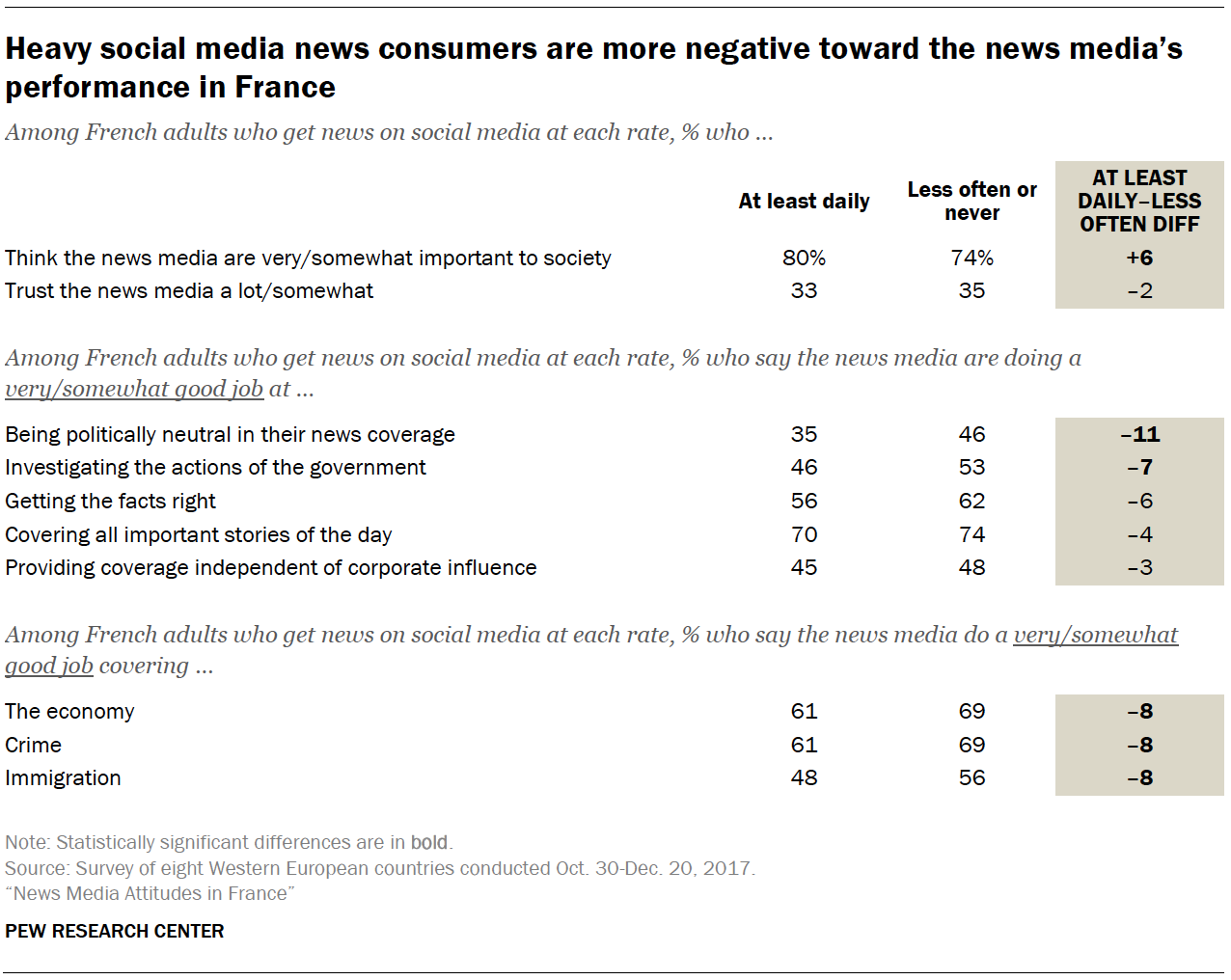

Heavy social media news consumers – those who get news on social media at least daily – are generally more negative toward the news media’s performance than those who get news on social media less often or those who do not use social media for news.

For each of the three topic areas asked about, coverage ratings are 8 percentage points lower among these heavy social media news consumers than among those who do not use social media as often or ever for news. And when it comes to the five core functions, those who often get news on social media again give lower marks on two measures – being politically neutral in their news coverage and investigating the actions of the government.

Despite more negative views of the news media’s performance, those who often get news on social media are more likely to value the news media. Eight-in-ten heavy social media news consumers say the news media’s role is somewhat or very important, compared with 74% of those who get social media news less often or never.

Differences in news media attitudes by age and education

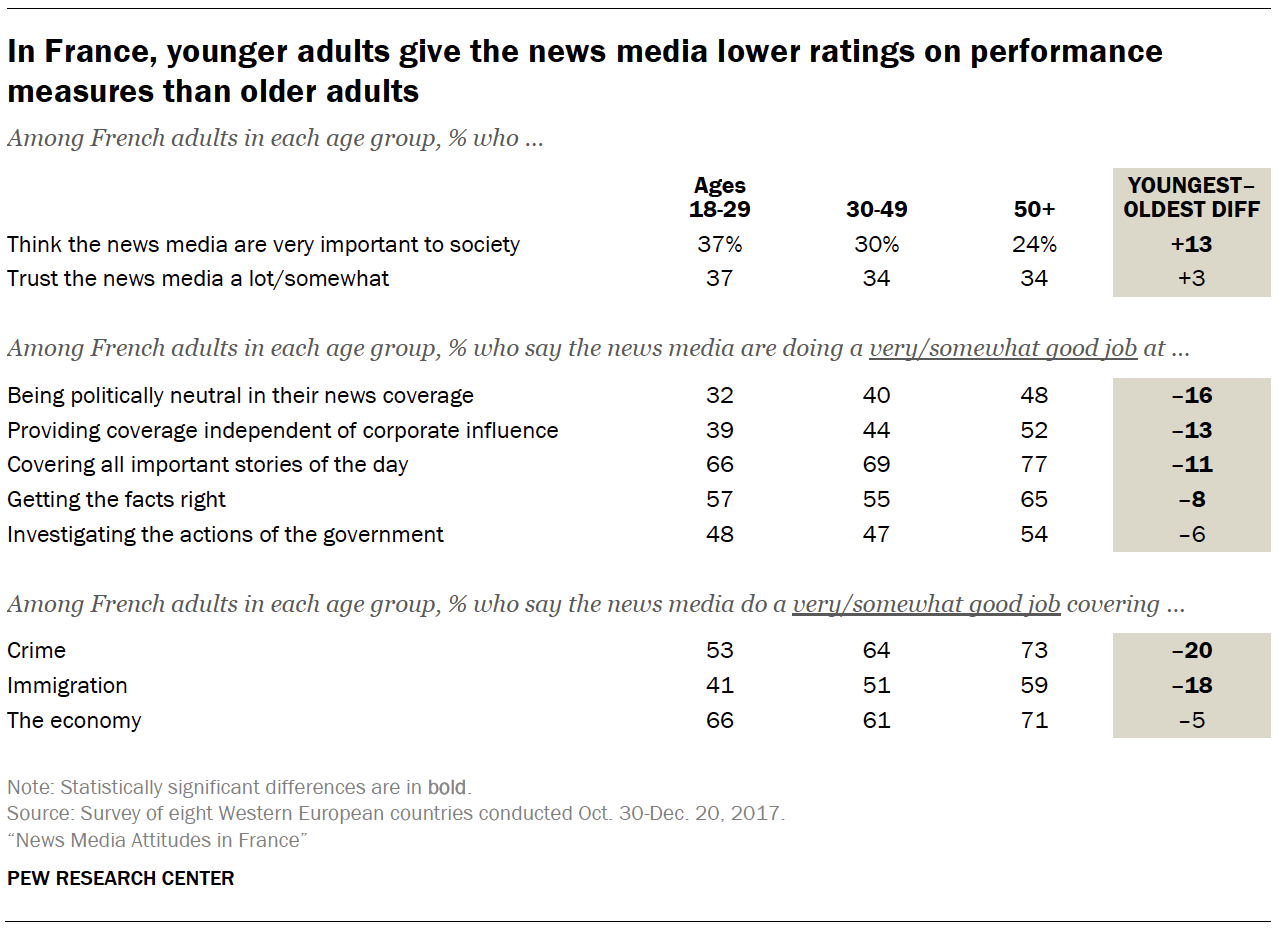

Younger adults are more likely than older adults to think the news media are important to society, but they also give them lower ratings on performance measures. For instance, 77% of adults ages 50 and older say the news media do a somewhat or very good job of covering all important stories of the day, while 66% of adults ages 18 to 29 say the same. The largest gap between the youngest and oldest groups is in whether the news media are politically neutral in their news coverage – a 16-percentage-point difference. Additionally, younger adults are less likely to give good ratings to news organizations’ coverage of two of the three topics asked: crime and immigration (by 20 points and 18 points, respectively).

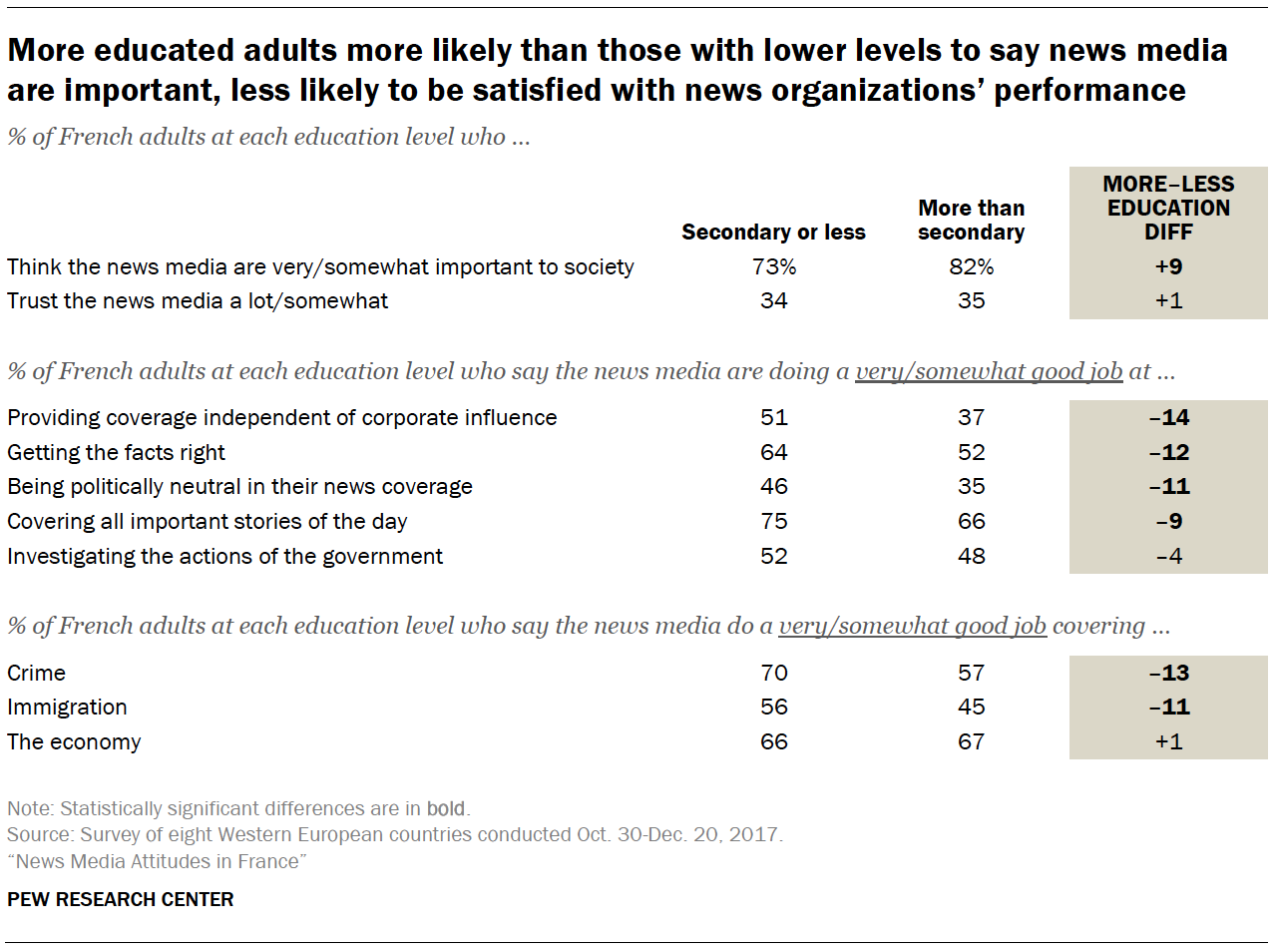

There is a similar narrative when looking at differences by education. Overall, French adults with high levels of education are more likely than those with lower levels to say the news media are important to society, but less likely to think news organizations are doing a good job.

Roughly eight-in-ten adults with more than a secondary education (82%) say the news media are very or somewhat important to the functioning of society, compared with about three-quarters of adults with a secondary education or less (73%). The more educated, however, are less likely to say the news media are doing a very or somewhat good job in four out of the five core functions, and they are similarly less approving of the news coverage of two topics – crime and immigration.1