How the Presidential Candidates Use the Web and Social Media

Obama Leads but Neither Candidate Engages in Much Dialogue with Voters

” target=”_blank” rel=”noopener noreferrer”>WATCH A NARRATED SLIDESHOW OF THE FINDINGS

If presidential campaigns are in part contests over which candidate masters changing communications technology, Barack Obama on the eve of the conventions holds a substantial lead over challenger Mitt Romney.

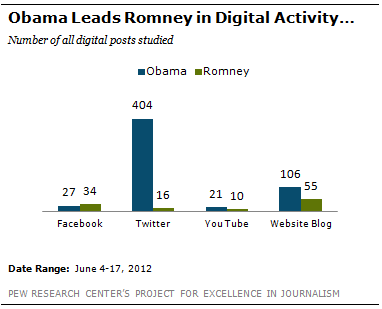

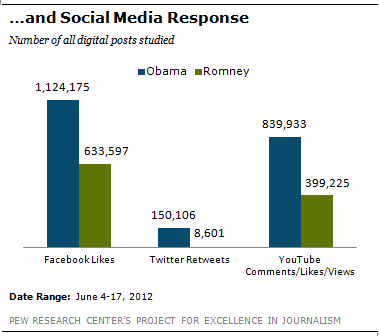

A new study of how the campaigns are using digital tools to talk directly with voters-bypassing the filter of traditional media-finds that the Obama campaign posted nearly four times as much content as the Romney campaign and was active on nearly twice as many platforms. [1] Obama’s digital content also engendered more response from the public-twice the number of shares, views and comments of his posts.

Just as John McCain’s campaign did four years ago, Romney’s campaign has taken steps over the summer to close the digital gap-and now with the announcement of the Romney-Ryan ticket made via the Romney campaign app may take more. The Obama campaign, in turn, has tried to adapt by recently redesigning its website.

These are among the findings of a detailed study of the websites of the two campaigns as well as their postings on Facebook, Twitter and YouTube-and the public reaction to that content-conducted by the Pew Research Center’s Project for Excellence in Journalism.

In theory, digital technology allows leaders to engage in a new level of “conversation” with voters, transforming campaigning into something more dynamic, more of a dialogue, than it was in the 20th century. For the most part, however, the presidential candidates are using their direct messaging mainly as a way to push their messages out. Citizen content was only minimally present on Romney’s digital channels. The Obama campaign made more substantial use of citizen voices-but only in one area: the “news blog” on its website where that content could be completely controlled.

The study of the direct messaging of the candidates also reveals something about the arguments the two sides are using to win voters. Romney’s campaign was twice as likely to talk about Obama (about a third of his content) as the president was to talk about his challenger (14% of his content). That began to change some in late July when the Obama campaign revamped its website.

And while the troubled economy was the No. 1 issue in both candidates’ digital messaging, the two camps talk about that issue in distinctly different ways. Romney’s discussion focuses on jobs. Obama’s discussion of the economy is partly philosophical, a discourse on the importance of the middle class and competing visions for the future.

This is the fourth presidential election cycle in which the Project for Excellence in Journalism has analyzed digital campaign communications. This year, in addition to the campaign websites, PEJ broadened its analysis to include an in-depth examination of content posted on Facebook, Twitter and YouTube, areas that were either in their infancy or that candidates made no use of four years ago. The study encompassed an examination of the direct messaging from the campaigns for 14 days during the summer, from June 4 to June 17, 2012, a period in which the two campaigns together published a total of 782 posts. The study also included audits of the candidates’ websites in June and again in late July.

The changes from 2008 go beyond the candidates adding social media channels. The Obama campaign has also localized its digital messaging significantly, adding state-by-state content pages filled with local information. It has also largely eliminated a role for the mainstream press. Four years ago the Obama campaign used press clips to validate his candidacy. The website no longer features a “news” section with recent media reports. Now the only news of the day comes directly from the Obama campaign itself. (In the recent redesign, the Obama campaign also highlighted its “Truth Team” section which includes its criticism of the Romney economic plan as well as their accounting of Obama’s initiatives-also as determined by the Obama campaign.)

The Romney website, by contrast, contains a page dedicated to accounts about the candidate from the mainstream news media, albeit only those speaking positively of Romney or negatively of Obama.

Among the study’s findings:

- Obama’s campaign has made far more use of direct digital messaging than Romney’s. Across platforms, the Obama campaign published 614 posts during the two weeks examined compared with 168 for Romney. The gap was the greatest on Twitter, where the Romney campaign averaged just one tweet per day versus 29 for the Obama campaign (17 per day on @BarackObama, the Twitter Account associated with his presidency, and 12 on @Obama2012, the one associated with his campaign). [2] Obama also produced about twice as many blog posts on his website as did Romney and more than twice as many YouTube videos.

- The campaign is about the economy, but what that means differs depending on to whom one is listening. Roughly a quarter, 24%, of the content from the Romney campaign was about the economy versus 19% of Obama campaign posts. But Romney devoted nearly twice the attention as Obama to jobs. Obama’s attention to the economy was almost equally divided between jobs and broader economic policy issues such as the need to invest in the middle class and how the election presents a choice between two economic visions. Another striking finding in the topics of the digital conversation is how much the agenda has changed in just four years. Gone from four years ago are web pages focused on veterans, agriculture, ethics, Iraq and technology. New are pages about tax policy-and the two campaigns overlap on fewer issues than Obama and McCain did.

- The economy may have dominated both candidates’ digital messaging, but it was not what voters showed the most interest in. On average Obama’s messages about the economy generated 361 shares or retweets per post. His posts about immigration, by comparison, generated more than four times that reaction; and his posts about women’s and veterans’ issues generated more than three times. This was also true of attention to Romney’s messaging. His posts on health care and veterans averaged almost twice the response per post of his economic messages.

- Neither campaign made much use of the social aspect of social media. Rarely did either candidate reply to, comment on, or “retweet” something from a citizen-or anyone else outside the campaign. On Twitter, 3% of the 404 Obama campaign tweets studied during the June period were retweets of citizen posts. Romney’s campaign produced just a single retweet during these two weeks-repeating something from his son Josh.

- Campaign websites remain the central hub of digital political messaging. Even if someone starts on a campaign’s social network page, they often end up back on the main website-to donate money, to join a community, to volunteer or to read anything of length. A July redesign of the Obama page emphasized the centrality of the campaign website further. Rather than sending users to the campaign’s YouTube channel, the video link now embeds the campaign videos directly into the website, where the only videos are the ones Obama wants you to see.

Obama’s digital strategy targets specific voter groups-as it did four years ago-to a greater degree than Romney’s.

Visitors to Obama’s website are offered opportunities to join 18 different constituency groups, among them African-Americans, women, LGBT, Latinos, veterans/military families or young Americans. If you click to join a group, you then begin to receive content targeted to that constituency. The Romney campaign offered no such groups in June. It has since added a Communities page that by early August featured nine groups.

How important is digital campaigning: does more digital activity really translate into more votes?

In 2004, Howard Dean used the web to generate early support and fundraising, but he failed to convert that into caucus or primary turnout. Barack Obama more successfully converted his use of the web in 2008 to stage an insurgent campaign and win younger voters.

But some may question whether younger voters were attracted to Obama because of his digital activity or whether Obama used digital platforms because it was a logical way to reach a natural voter base.

While there may be no simple answer, throughout modern campaign history successful candidates have tended to outpace their competitors in understanding changing communications. From Franklin Roosevelt’s use of radio, to John F. Kennedy’s embrace of television, to Ronald Reagan’s recognition of the potential for arranging the look and feel of campaign events in the age of satellites and video tape, candidates quicker to grasp the power of new technology have used that to convey a sense that they represented a new generation of leadership more in touch with where the country was heading.

PEJ began studying the role of digital technology in presidential politics in 2000. In our first report, “ePolitics,” candidate websites were yet to emerge; news websites and “web portals” were the gatekeepers of digital campaign information. PEJ that year studied 12 of the most popular sites and portals providing campaign news, a list that included Salon, the Washington Post and Netscape. The study found an emphasis on updating tidbits of information throughout the day, so much so that sometimes the most important event of the day-or week-never became headline news. On February 28, 2000, for instance, AOL never led with John McCain’s speech in Virginia Beach attacking Pat Robertson and Jerry Falwell, even though it was not only the story of the day but a critical event of his campaign.

In 2004, PEJ re-examined the sites still in existence (and added two others); websites that year made a significant push toward offering users a chance to compare candidates on the issues-something almost entirely absent in 2000. News websites were also beginning to provide opportunities for users to manipulate and customize information; navigation, however, was often difficult. It was also the election cycle in which candidate Howard Dean transformed political campaigns by becoming the first candidate to use blogging, to use his website to organize “meetups,” and to use other internet technology as a major part of his campaign.

By 2008, candidate websites were standard, and campaigns were clearly taking steps to try to control their message in ways that bypassed the traditional media. This was the year that Hillary Clinton announced her candidacy on her web page; and Barack Obama, albeit not entirely successfully, announced Joe Biden as his running mate on his website. Obama also used his site widely to invigorate a national grass roots campaign and built substantially on Dean’s 2004 efforts to raise millions in small donations using the web. Our analysis also found that different candidates’ campaigns differed widely in how well each had mastered technology.

In 2012, in short, voters are playing an increasingly large role in helping to communicate campaign messages, while the role of the traditional news media as an authority or validator has only lessened.

Footnote

1. For the time period studied (June 4, 2012 to June 17, 2012), this report considered those platforms that the candidates’ respective websites listed and linked to.

2. This report studied the candidate’s twitter accounts that the two campaigns linked to from their website homepage. There is another verified Romney campaign Twitter account, @TeamRomney, but it is not listed or linked to from MittRomney.com, and thus was not formally associated with the campaign in the same way as other content streams. Nor did the main Twitter account, @MittRomney, retweet or link to posts from @TeamRomney, at the time of the study. Researchers did count the tweets from @TeamRomney during the time of the study, June 4 – June 17, 2012. There were a total of 63 tweets which would bring the average activity across the two Romney accounts from one to 6 per day.