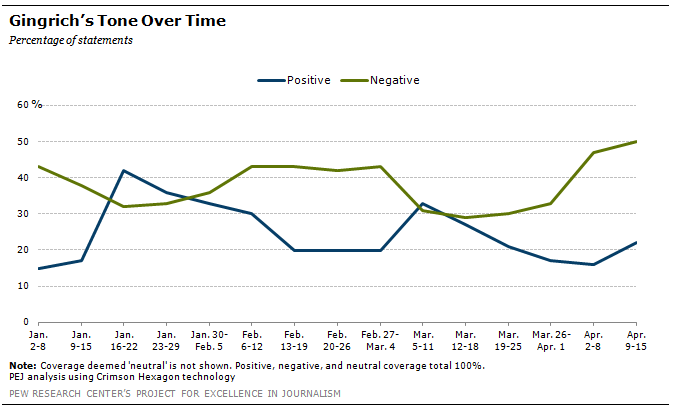

Late in 2011 Newt Gingrich was briefly the GOP frontrunner, according to some polls. Once the primaries and caucuses actually began in January, however, Gingrich only enjoyed a single week in which positive coverage about him significantly outweighed negative, the week he won the South Carolina primary.

And the momentum lasted just about one week.

After the media concluded that Gingrich was outdebated in Florida, and he was subsequently beaten by Romney in the primary there, his narrative sunk back into negative territory, where it largely stayed. All told, in the 15 weeks of primary contests studied in 2012, Gingrich endured 10 weeks of substantially more negative than positive coverage and four others when it was mixed between positive and negative.

And even the mixed narrative ended some time ago. The last week when Gingrich’s coverage was divided (27% positive, 29% negative and 44% neutral) was March 12-18, shortly after his one Super Tuesday win in his home state of Georgia. For the next month, his coverage became increasingly more negative than positive—by a margin ranging from 9 points to 31 points.

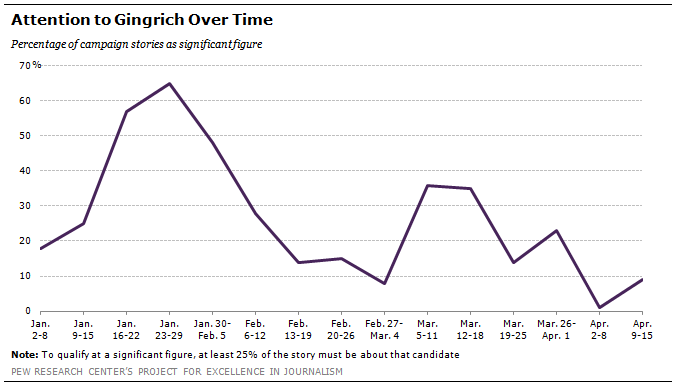

And that coincided with a shrinking amount of attention to his campaign. Gingrich’s high water mark in media exposure also coincided with his win in South Carolina. In the last two weeks of January, he was the top newsmaker in the Republican field, registering as a significant presence in 57% and 65% of the campaign stories. Then it was over. From mid-February through early March, press attention dropped dramatically, and he never registered as a significant focus in more than 15% of the stories in a week.

He had two more weeks of substantial attention, but this was a mixed blessing. From March 5-18 Gingrich saw attention increase to the point that he was a significant newsmaker in more than one-third of the stories studied. Some of that was attributable to his March 6 win in Georgia, but the victory was followed within days by a spate of stories wondering if and when he would end his candidacy, given that he did not fare better in other Southern states besides his own.

By the first week of April, Gingrich’s coverage plunged to less than 1% of campaign stories after he announced downsizing his staff but continuing to run.

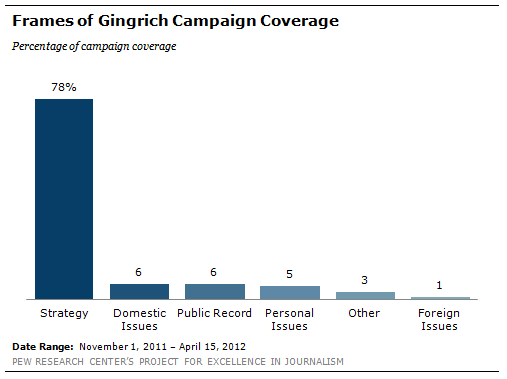

The way the media framed Gingrich’s campaign was similar to that of other candidates. Overall, 78% of the Gingrich campaign coverage from Nov. 1-April 15 was about momentum, fundraising and advertising. That swelled to 88% in March and early April, as it became increasingly clear he would not win the race. From November through mid-April, 12% of the coverage focused on his personal life and public record.

On the personal side, the vetting of Gingrich was often very personal. His marital history, always considered a potential problem area for his campaign, exploded into headlines in late January when his second wife, Marianne, claimed he asked her for an “open marriage.”

Many of the stories about his public record honed in on his controversial tenure as Speaker of the House (1995 to 1999) when he was fined for ethical violations and ultimately stepped down from the post. The heaviest press focus on that public record (10%) came in November and December 2011.

Gingrich’s positions on the issues accounted for 6% of his coverage. While economic policy made up a large portion of the coverage featuring Gingrich, his stance on immigration—which he termed as “humane,” but critics labeled as amnesty—received considerable attention in November and December. At that point, it appeared that Gingrich, rather than Santorum, would emerge as the chief rival to Romney.