The customization or targeting of ads based on audience data is one of the newer ways to serve advertisers interests-helping those selling goods to reach consumers perceived to be the most likely to be interested in and thus to act on their ads. In targeted advertising, in other words, the ads one person gets will differ from what another person receives, depending on their online purchase history, location and/or personal habits, even if they click on the same website at essentially the same time.

The advertising industry has consistently suggested to digital publishers that offering more precise and actionable information about their visitors will result in publishers’ ability to charge higher prices per thousand impressions (CPMs) served. As Joe Turow shows in his new book, The Daily You, the huge competition among publishers and advertising networks has tended to push down CPMs despite continual increases in targeting publishers offer. As Turow notes, an entire ecosystem of organizations-including supply-side platforms, yield optimizers and premium-publisher consortia-counteracts this downward pricing spiral.

To what extent have news organizations adopted the practice? And to what extent can users eliminate the targeting by taking certain steps like clearing their "cookies," a small text file that tracks and saves the user’s behavior.

To try to answer this, researchers examined each website through multiple user identities.

Overall, only a handful of sites exhibited high levels of targeting. A few more had a moderate level of targeting. Most showed no signs of targeting at all.

The study also found that for the sites that do target, the common step of removing cookies did not eliminate the targeting.

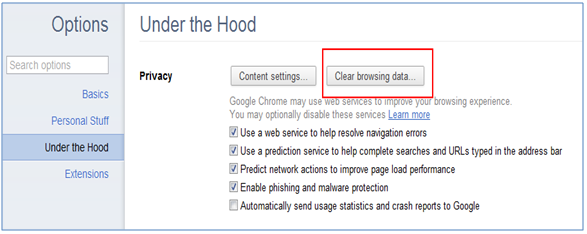

Targeting can be built off of several different analytics, including cookies that follow users’ browsing history, Web bugs[1] that allow advertisers to track customers remotely and a person’s Internet Protocol (IP) address, which provides location and social media activity information. In this study, it was not possible to control all of the bases for targeting ads; as a result, we controlled for one of the earliest and most common methods and the one easiest to do as a consumer.[2] It involves clearing your browsing history, cookies and cache. In most modern browsers this is a simple matter of clicking a button.

To do this, each website was coded by two researchers two different times: once through his or her regular browser, which included the researcher’s internet history and cookies, and once using a "clean" browser, in which all cookies, browsing history and cache were erased.[3] Researchers measured the level of targeting that occurred through their regular (cookie-enabled) browsers.

Overall, just three of the 22 sites exhibited high levels of targeting, defined here as at least 45% of the ads were different from one user to the next.[4] (No more than 67% of the ads were different on any of the sites studied.) Three other sites had medium levels of targeting where between 29% and 40% of the ads were different across users. The majority, 15 of the 22 sites studied, involved minimal, if any, use of targeted ads.

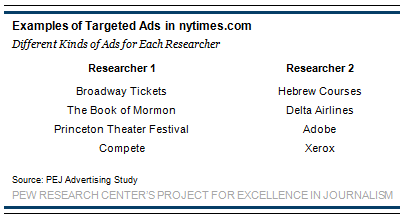

CNN, Yahoo News and The New York Times, all in the top 10 new websites in audience, had the highest degree of targeting. Different users visiting from their regular computer were served different ads, and the ads each received matched up with their recent online activity. For nytimes.com and CNN.com, nearly half (47% and 45% respectively) of the ads were different for the two users. On Yahoo News the targeting was even more prevalent; roughly two-thirds, 67%, of the ads differed for each person.

The ads that tended to be the same on these sites were the in-house ads, promoting the organization’s own products. On nytimes.com, for example, all users received the same ad for a New York Times subscription. They also received the same financial industry ads (all on the homepage). Beyond those, however, all other ads were tailored to the user-both the number of ads and what ads they saw.

User 1, who regularly follows the communications industry, received 13 telecom ads across two visits; User 2 saw only two telecom ads. User 1 also saw nine ads that dealt with schools and colleges (while the other user saw two), and he received ads for Broadway tickets, which he was looking to purchase in the past days. The second user instead saw ads on Hebrew classes, something for which she had been searching recently, as well as for Delta airlines, on which she often travels. The ads served to each person indicate not only a high level of targeting but also targeting very closely tied to interests and activities. Similar levels of difference between the two users occurred on CNN.com and Yahoo.com.

On three other news websites, CBS, USA Today and MSNBC, the researchers encountered more moderate levels of targeting. On usatoday.com, for example, both researchers received the same financial ads (GE Capital and consumer refinance ads) and self-promotion ads (USA today subscription options) more than any other ad. Some ads did differ, though. User 1 received ads for schools and colleges (NYU and Cornell), consumer electronics (Casio and HTC), and cars (consumer auto source ads). The ads that appeared for User 2 came primarily from broad private corporate companies (Cargill, Ebay and UPS) as well as the communications (Verizon) and insurance (State Farm) industries.

On 15 more sites, researchers found only limited signs of targeting, 10% or less. For these, the top four categories of ads were nearly identical from one user to the next. These news sites with lowest level of targeting, if any at all, were local newspapers and magazines-especially the Toledo Blade, The Hour, Joplin Globe and Newsweek.

Once researchers identified the six sites with high and medium levels of targeting, they then took the next step of seeing whether entering the site from a "clean" or unidentified browser made a difference. In other words, did it negate the ability to target ads? The short answer is no. The most conventional means for a user to opt out of tracking cookies proved ineffective here.

For all six of these sites, the advertisements the user received remained the same even after taking steps to erase signs of their identity or history from the browser. On news.Yahoo.com, for example, clearing a user’s history had no impact on the ads served, and those ads were very different across the two users. User 1 repeatedly got ads by Kayak, a travel search engine, Verizon and Bank of America, while User 2 saw ads by LivingSocial, Hyatt and TransUnion, one of the largest credit bureaus in the U.S.

In the case of CBS News, cookies also had no influence on the level of targeting. Each researcher got the same ads whether entering through the cookie-enabled or cookie-stripped browser. Users kept getting the same ads when they individually visited the site; however, when compared, the ads between the two users were different. User 1 received health and medicine related ads from the Coleman Institute and Everyday Lifestyles, regardless the usage of cookies and the kind of browser. These ads did not appear for User 2, who instead saw prescription drug ads regarding joint relief and aging (Instaflex and Proleva).

One question that emerges is whether targeting has more or less natural appeal on some websites than others. In other words, do national sites with their larger and more diverse audience pools lend themselves more naturally than smaller sites to the benefits of ad targeting? On the Toledo Blade’s site, for example, are there enough people to fit into different ad cohorts to make targeting worthwhile? The sites with the higher levels of targeting were the larger more nationally oriented sites. At the same time, though, that could just as likely be a function of greater in-house technical knowledge and resources to spend developing the online ad system. It takes not only a diverse audience but also technical know-how to establish these parameters.

Finally, on a few sites, there was evidence of another method of targeting-not according to users but according to news story. On a number of occasions, there was a close relationship between the content of the story and the ads displayed. For instance, on July 11, 2011, when The Atlantic online was studied, there was a story entitled "The Navy’s Green Devices: Coming to a Store Near You?" which discussed military green initiatives. The ads surrounding the story were by Shell and specifically promoted clean energy and natural gas. Same case with the Arizona Republic, where the first story studied was about Arizona’s Clean Car Program and most of the ads were by the automotive industry.

Footnotes

[1] Web bugs are 1×1 pixel pieces of code that allow advertisers to track customers remotely. Unlike a cookie, which can be accepted or declined by a browser user, a Web bug arrives as just another GIF or other file object. It can usually only be detected if the user looks at the source version of the page to find a tag that loads from a different Web server than the rest of the page. http://searchsoa.techtarget.com/definition/Web-bug

[2] An additional factor that could not be controlled for but could explain some of the differences on certain sites is the fact that different websites serve ads in different ways. Some sites, like Yahoo News, rotate their ads frequently and can change even as you are reading a story. CNN, on the other hand, generally doesn’t change its ads even if you refresh the page.

[3] For both kinds of visits researchers did not login through their online subscription or personal account.

[4] In the recheck of the sites on Jan. 27, 2012, two sites, latimes.com and theatlantic.com, showed increased levels of targeting. They moved from having virtually no targeting to mid-level targeting.