Introduction

At the ripe old age of ten, the current incarnation of the Napster music service scarcely resembles its former bawdy self. If the original Napster was a loud, raucous garage band made up of drunken college students, the present offering is what happens when the band sobers up, signs to a major label, and starts house hunting.

Long gone are the days of free-flowing music from the vine of central servers. Today’s Napster requires a grown-up kind of commitment: a credit card and a monthly subscription. It also faces stiff competition; while Napster morphed from its lawless larval stage to a dues-paying music service, consumers in search of free content have had their pick of surviving peer-to-peer applications and torrent sites that more than make up for the loss of the original rogue site.

The current economic climate makes music an even tougher sell. In today’s economy, how do you compete with free? While it may seem counterintuitive, some experts see consumers’ insatiable appetite for free content as an opportunity rather than a cause for concern. Chris Anderson, author of The Long Tail and Editor-in-Chief at Wired ignited a fiery debate among the technology and entertainment community recently when he published an article touting free content as the key to earning income in the digital age. His article, titled, “Free! Why $0.00 Is The Future Of Business,” argues that when digital content approaches zero marginal cost to distribute, the more you give away for free, the more you can sell to the small segment of consumers who are willing to pay for premium content.1

For today’s Napster, that means that along with the unlimited streaming capability that a monthly $5.00 subscription fee buys, the listener also scores five “free” digital downloads with no strings attached. For some artists, Anderson’s scenario translates into giving away the entire album for free in hopes that fans will pay for concert tickets or limited access to live streaming video from the road. What’s clear at this point in the evolution of the music business is that there is no clear business model. In the internet age, selling recorded music has become as much of an art as making the music itself.

While the music industry has been on the front lines of the battle to convert freeloaders into paying customers, their efforts have been watched closely by other digitized industries—newspapers, book publishing and Hollywood among them—who are hoping to staunch their own bleeding before it’s too late. And if the music market is any indication of how consumer expectations will evolve elsewhere, the demands for free content will extend far beyond the mere cost of the product.

In the decade since Napster’s launch, digital music consumers have demonstrated their interest in five kinds of “free” selling points:

- Cost (zero or approaching zero),

- Portability (to any device),

- Mobility (wireless access to music),

- Choice (access to any song ever recorded) and

- Remixability (freedom to remix and mashup music)

All of this makes for a tall order, but if history is any guide, music consumers usually get what they want.

Free music makes the network wealthy

As researchers look back on the first decade of the 21st Century, many will no doubt point to the formative impact of file-sharing and peer-to-peer exchange of music on the internet. Distributed networks of socially-driven music sharing helped lay the foundation for mainstream engagement with participatory media applications. Napster and other peer-to-peer services “schooled” users in the social practice of downloading, uploading, and sharing digital content, which, in turn, has contributed to increased demand for broadband, greater processing power, and mobile media devices.

Internet scholar Lawrence Lessig has even gone so far as to argue that music was the most important catalyst to early adoption of the internet. As he notes in Free Culture, “The appeal of file-sharing music was the crack cocaine of the Internet’s growth. It drove demand for access to the Internet more powerfully than any other single application.” 23

Media analysts now broadly use the term, “Napsterization” to refer to a massive shift in a given industry where networked consumers armed with technology and high-speed connectivity disrupt traditional institutions, hierarchies and distribution systems. And in many cases, those consumers have come to expect that a digitized version of a product—such as news, movies or television shows—should be available online for free.

Yet, the current reach of this Napsterization effect extends far beyond the media industry; patients are sharing peer-to-peer expertise on coping with medical conditions and are engaged in efforts to gain free access to vaulted personal health records, citizens are networking to increase oversight of politicians and are demanding unfettered access to government data. Even online daters—one of the few segments of the internet universe willing to pay at the gates of the walled garden—are circumventing the paid services and connecting directly via free social networking sites.

Partying like it’s 1999—until the subpoenas come in

Music critic Sasha Frere-Jones has referred to the plight of the music industry as the “canary in the economic coal mine,” citing it as “a small example of the enormous financial buckling that is now global.”24 If the music business was the canary, then the MP3 was its carbon monoxide, choking an industry that had built its empire on the clean, regulated air of analog music products. First, music went digital. Then the MP3 compression format shrunk those big music files into transportable size. After that, there was little hope of record companies making it out of the mine without some serious lung damage.

Napster arrived at a time when tightly controlled access to new music was still the norm. While online radio stations were starting to flourish, music lovers were becoming disillusioned with the homogenizing effects of terrestrial radio consolidation that was enabled by the 1996 Telecommunications Act. Their frustrations were made clear when the Federal Communications Commission reviewed these rules in 2003 and opened them up for public comment. The FCC received more than 15,000 letters, emails and other documents. This was one of the largest responses in FCC history, with most writing in to oppose further media consolidation.25 Before Napster, internet users had limited access to digital music through legitimate channels. After Napster’s software allowed fans to share their entire catalog of music files online, the music ecology radically changed.

The revolutionary file-sharing application created by college student Shawn Fanning officially launched in June of 1999. By November, the file-sharing network had grown so popular that it had attracted the first of many peer-to-peer-focused lawsuits from the RIAA. And by the time the Pew Internet Project fielded its initial survey on music file-sharing in July 2000, nearly one in four adult internet users said they had downloaded music files, and most of them (54%) had used the Napster network to do so.26

The musical bacchanalia that consumers experienced at the height of Napster’s popularity prompted many industry observers to declare record labels obsolete long before sales figures had shown any serious decline. A New York Times article that ran during the summer of 2000 described the scenarios put forth by industry experts:

In the none-too-distant future, techno-visionaries declare, musicians will not need record labels. Instead, they will market and sell recordings directly to fans over the Internet. Even the labels that manage to hang on to their artists will find their sales eviscerated by piracy. With free music available on the Web via Napster and other song-trading services, only fools will pay for songs.27

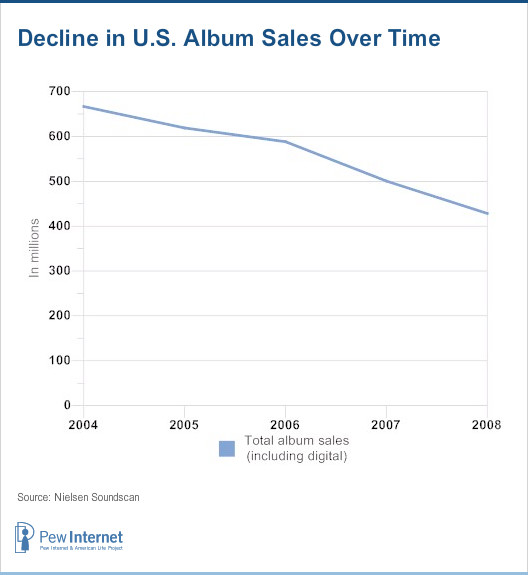

Yet, in 2009, there are plenty of fools among us, and the record labels are still hanging on to their broken strings. Granted, consumers aren’t spending as much on music as they used to. Record sales for the music industry continue to decline; the latest reports from Nielsen indicated that total album sales, including albums sold digitally, fell to 428.4 million units, down 8.5% 14% from 500.5 million in 2007.28

And while digital album sales actually increased 32% during the same period—to a record 65.8 million units—they were still dwarfed by the 362.6 million physical units sold. Pew Internet Project data echoes these findings; the market for digital music is still in its infancy, and those who do continue to buy music still overwhelmingly choose CDs. According to our 2008 “Internet and Consumer Choice” report, just 13% of music buyers say their most recent music purchase was a digital download.29

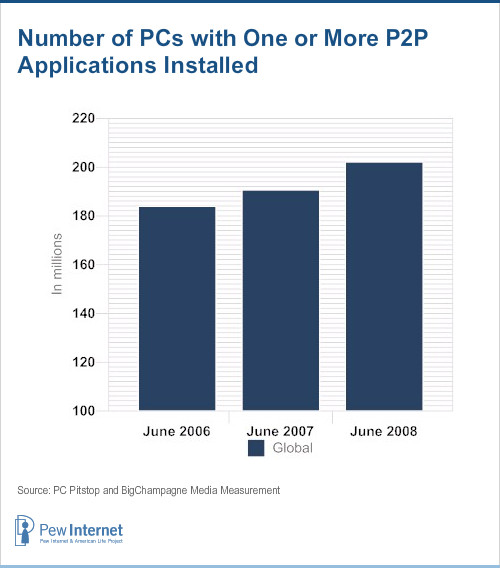

At the same time, unauthorized file-sharing venues are still firmly rooted in the online music world. In a recent Pew Internet Project survey, 15% of online adults admitted to downloading or sharing files using peer-to-peer or BitTorrent.30 Globally, estimates from file-sharing research firm Big Champagne place the P2P universe at more than 200 million computers with at least one peer-to-peer application installed, and operators of the popular Pirate Bay torrent tracker have identified more than 25 million “peers” who have used their site alone to exchange files.31

And among that 13% of music consumers who do pay for downloads, there’s no doubt that the eight-year-old iTunes service continues to dominate the market. Yet, as robust as the iTunes catalog may be, there are still surprising holes in the store’s offerings. Popular artists such as AC/DC still do not have licensing deals with Apple, and many older albums from independent artists like Silver Sun have never made it to iTunes’ digital shelves. Music fans in search of these recordings are still more likely to find them on peer-to-peer networks, torrent trackers, and eBay.

And then the suits dropped their suits…

Until recently, every frustrated fan who turned to unauthorized sources to acquire and share music faced the prospect of a lawsuit from the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA). The industry’s legal battle against individual file sharers spanned roughly five years, targeting more than 35,000 alleged file sharers in the U.S.32 However, at the end of that costly campaign, the challenge of plugging the P2P hole proved to be insurmountable, and critics largely viewed the litigation as ineffective.33 In the latest issue of the New York Law Journal, intellectual property expert Alan J. Hartnick offers one such negative assessment of the legal campaign, stating: “The lawsuits had little effect, as unlawful downloading continues.”34 Also lost down the P2P hole was the reputation of the industry, now widely seen as one that sues its own customers and is out of step with current technology. “The record companies have created this situation themselves,” said Simon Wright, CEO of Virgin Entertainment Group in a 2007 Rolling Stone article.35 More recently, a Boston Globe editorial echoed the popular sentiment that the industry missed their chance to harness the internet for music distribution with Napster:

Sharing music without permission is a violation of copyright, as the industry contends, but digital technology makes downloading music off the Internet inevitable. The industry missed an opportunity to turn informal file-sharing into a profit center when it failed to buy Napster, the first of the popular downloading services, when it had a chance in 2000.36

But for all of Napster’s influence, it’s easy to forget that the demographics of music buyers actually started to shift before Napster’s launch. An eerily prescient article that ran in Billboard in April of 1999 reported that the record industry had seen a puzzling drop in music-buying by young listeners during the previous year. The biggest decrease was noted among the college-aged set (20- to 24-year-olds), who bought only about half as many recordings as their older brothers and sisters did in the decade prior.37 Hillary Rosen, head of the RIAA at the time, described the changes they had observed in the market:

Rosen says that the industry is facing an aging record-buying audience and must further stimulate younger listeners to own prerecorded music. “All of the surveys show that across the demographic, music is incredibly important,” she says. “What we’re finding is that the disconnect occurs between the importance of music in people’s lives and their need to own it. We clearly have a task as an industry to re-energize the desire to own music among young people.”

That the labels would eventually attempt to re-energize young people’s desire to own music through lawsuits was predicted and warned against nearly three years before the campaign began. In May of 2000, Steve Sutherland, editor of nme.com and moderator at the NetSounds conference, predicted that high profile legal cases against individuals were inevitable, but foolhardy: “Let them sue an individual, I’m sure they will. It will backfire though. There will be such an outcry if an individual were prosecuted….”38

The industry met the outcries from music-sharing fans by arguing the morality of its case: Taking CDs from a record store was wrong, why should taking digital music online be any different? However, when artists spoke on the industry’s behalf, they didn’t always present a unified message that sharing music in any context without permission was wrong. While Metallica became the iconic anti-file-sharing band, there were many other artists who weren’t so quick to decry the networks and the openness of the MP3 format.

As early as January 19, 1999, musical icons like David Bowie were singing the praises of the MP3 and the potential for fans to remix his music easily:

A few days ago a kid downloaded one of my songs from my Web site. He re-recorded it at home, changing the bits that he didn’t like and then put up his version on his own site. The new version is written his way, with changes to the melodies and some of the lyrics and it is available as an MP3. It is unbelievable. If he can do that, imagine what can happen in the future.39

Of course, many music downloaders were more interested in simply acquiring music for free than they were remixing and sharing what might be considered transformative creations with the world. But even the “freeloaders” were not always shunned by the artists whose work was being shared. The rock band Wilco famously was one of the first acts to benefit tremendously from the promotional power of peer-to-peer. After being dropped by their label in 2001, the band decided to release their album, “Yankee Hotel Foxtrot,” for free online. The resulting swarm of listening and sharing by fans ultimately convinced the label to offer the CD version of the album for sale in 2002. And while the band’s previous recording, “Summerteeth” had sold just 20,000 copies, “Yankee Hotel Foxtrot” quickly surpassed the 500,000 mark. Shortly after, Jeff Tweedy, the lead singer of Wilco, began speaking out in support of file-sharing, expressing little patience for the Metallicas of the world: In a 2005 New York Times article, he suggested that downloading was an act of rightful ”civil disobedience” and was quoted as saying, ”To me, the only people who are complaining are people who are so rich they never deserve to be paid again.”40

Artists’ varied views on the impact of file sharing were also documented in Pew Internet’s “Artists, Musicians and the Internet” report from 2004.41 While most artists we interviewed believed that unauthorized online file sharing was wrong, few felt the industry was in peril because of the networks. When asked about the threat peer-to-peer file-sharing posed to creative industries at the time, two-thirds of artists said the activity posed only a minor threat or no threat at all to them. Further, there were some major divisions among them about what constituted appropriate copying and sharing of digital files. Yet, among those who were both successful and struggling, the artists and musicians we surveyed were more likely to say that the internet had made it possible for them to make more money from their art than they were to say it had made it harder to protect their work from piracy or unlawful use.

And now, while it’s hard to argue at present that the industry as a whole didn’t suffer some serious losses due to Napster and its progeny, it’s also hard to ignore those artists who have benefited from the shift in distribution and promotion that has emerged post-Napster. Megaband Radiohead launched one of the bolder experiments to date, self-releasing its “In Rainbows” album on October 10, 2007 for download from their website under a “pay what you can” model. So far, the album has sold over three million digital and physical copies—more than each of their previous two albums. Similarly, the band, Nine Inch Nails, self-released their, “Ghosts I-IV” album in March of 2008 in a variety of formats online. In addition to free files which the artists directly uploaded to file-sharing networks themselves, the band offered a $5 digital version and premium packages (including various limited-edition physical merchandise) that generated $1.6 million in just over a week’s time.42 And although the entire album was available for free through a Creative Commons license, it eventually became the bestselling MP3 album at Amazon for all of 2008.43

Done Restricting Music: The end of DRM and the future of music online

The success of the Radiohead and Nine Inch Nails experiments would be the prologue to an industry-wide loosening of the ties around digital distribution. Shortly after the RIAA had announced the end to its litigation against individual file sharers at the end of 2008, iTunes halted the sale of music bundled with “digital rights management” protection.

Digital rights management (DRM) has been defined by the Federal Trade Commission as “technologies typically used by hardware manufacturers, publishers, and copyright holders to attempt to control how consumers access and use media and entertainment content.”44 DRM has made its way into everything from cell phones to in-flight entertainment systems. Many consumers have encountered the restrictions firsthand when trying to make copies of purchased music or transfer songs to mobile devices.

Apple’s iTunes music service pioneered the widespread use of DRM that came bundled with the purchase of individual digital music files online. Among the various restrictions embedded in the files were limits on the number of computers that could play the songs and the kinds of software and portable devices that could be used to listen to the music. These restrictions and assurances that the files would not be widely redistributed online were necessary for Apple to acquire the licensing they needed from the record labels to sell the music in the first place. However, after years of negotiations, the labels agreed to drop those protections in exchange for the right to variable pricing on iTunes. And now that iTunes and many other legitimate digital music offerings are DRM-free, the labels have effectively set a new industry standard in freedom and flexibility for consumers.

This belated embrace of the infinitely shareable music file comes only after lots of clumsy dancing with DRM. For every new copy protection scheme that has emerged, there have been hundreds, if not thousands, of hackers waiting in the wings to expose the technology’s flaws and share their discoveries with the world. One of the most famous hacks in music DRM history involved nothing more than the use of a Magic Marker to disable the copy protection built into CDs.45 And while DRM-protected music undoubtedly became more sophisticated over the years, it remained a tough sell to consumers when unauthorized copies of songs unfettered by DRM were so widely available for free.

In the Pew Internet Project’s third Future of the Internet survey, experts were asked to ruminate about the future of copyright protection. Many responses referenced the limitations of the technology and the ways consumer resistance to DRM would influence the market. Sociologist and author Howard Rheingold noted that “both iTunes and Amazon are stripping DRM from downloadable music because that is what music customers demand.” Likewise, Geoff Arnold, senior principal and software development engineer for Amazon.com offered that consumers armed with increasingly powerful technology would likely retain the upper hand in the DRM arms race: “Every individual will have access to sufficient computing power to simulate every relevant content consumption use-case, and DRM won’t be able to keep up.”

So, without DRM, will anyone pay for recorded music in the future? When Pew Internet surveys show that 75% of teen music downloaders ages 12-17 agree that “file-sharing is so easy to do, it’s unrealistic to expect people not to do it,” one wonders if a generation weaned on free music will ever consider music worth paying for.46

Yet, for all the major changes in the industry’s tactics, the relaxed attitude only goes so far. Through digital fingerprinting and other tracking technologies, the record labels are monitoring copyrighted content as closely as ever and are counting on two major new strategies to help them: First, is a landmark partnership with internet service providers to monitor file sharing activity and potentially cut off service to the worst offenders. Second, is a series of partnerships with universities that would incorporate music subscription fees (predicted to be less than five dollars per student) into student tuition bills.47 If successful, a similar ISP-based fee could be implemented for the general public.

The subscription model has been tossed around for more than a decade, with proponents arguing that music—and any kind of copyrighted content—gains more value as it is widely distributed.48 Blanket fees assure that artists are paid for their work, and consumers have the freedom to listen to music on any device and in any location they choose. And as music consumption becomes increasingly mobile, the labels have begun to experiment with all-you-can-eat music download plans like Nokia’s “Comes With Music” plan which is bundled with the purchase of a cell phone. At the same time, free streaming music services continue to fill an important and growing niche; Pandora and imeem have recently unveiled iPhone apps that allow users to access their accounts and listen to music on the go.

Looking ahead, as users’ engagement with cloud computing activities becomes more pervasive and seamless, there may come a time when the difference between downloading and streaming music files becomes moot. At the moment, Pew Internet Project data shows that 69% of online Americans have already taken advantage of some form of cloud computing such as using webmail services, storing data online, or using other applications whose functionality is located on the web.49 As more and more internet users acquire smart phones and high-speed wireless connectivity improves, music consumers get ever closer to the “celestial jukebox” dream of any song at any time that started during the days of Napster. For now, quality and reliability are still an issue, but the march of technology will quickly stomp out that minor hurdle. Ultimately, whether you’re storing a library of music files on your home computer or streaming songs through your iPhone, it all becomes the same: instant access to the music you want.