Health professionals, friends, family members, and fellow patients are all part of the mix.

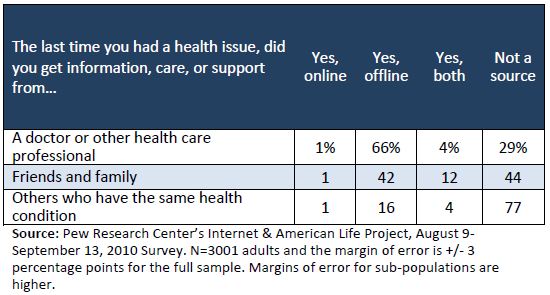

When asked about the last time they had a health issue, 71% of adults in the U.S. say they received information, care, or support from a health professional. Fifty-five percent of adults say they turned to friends and family. Twenty-one percent of adults say they turned to others who have the same health condition.

The majority of these interactions happen offline: just 5% of adults say they received online information, care, or support from a health professional, 13% say they had online contact with friends and family, and 5% say they interacted online with fellow patients.

People living with chronic conditions are more likely than those who report no conditions to say they turned to a health professional: 79%, compared with 63%. Both groups are equally likely to say they received information, care, or support from friends and family. One in four people living with chronic conditions (25%) say they got information, care, or support from other people who have the same health condition the last time they had a health issue, compared with 19% of adults who report no chronic conditions. Again, adults who report that they have a condition other than the five named in the survey are the most likely group to turn to fellow patients for counsel. Fully one-third of this group (31%) has done so. In all cases, most of the communication happens offline.

Rare conditions necessitate online consultation with peers.

A significant limitation of the online survey we conducted with NORD is its reliance on a sample of people who have already found a community of those who share their condition. Since it is not a representative sample of people living with rare disease, the responses cannot be directly compared to the national telephone survey results. However, it is interesting to look at the patterns in the data, and in this case, the patterns are strikingly different from the results we got in the telephone survey.

When asked the same question about the last time they had a health issue, the people living with rare disease who responded to the survey far outpaced all other groups, including those living with chronic conditions, in tapping the wisdom of their peer network. More than half of rare-disease respondents say they turned to family and friends. Another majority say they turned to others who have the same health condition. Much of their interaction with friends, family, and fellow patients or caregivers happens online by necessity, since they are unlikely to live near to the people who share their conditions.

Yet again, it is critical to note that health professionals were the most popular choice even among this highly-networked group of people living with rare conditions. The oft-expressed fear that patients are using the internet to self-diagnose and self-medicate without reference to medical professionals does not emerge in national phone surveys or in this special rare-disease community survey. Advice from peers is a supplement to what a doctor or nurse may have to say about a health situation that arises.

A woman who cares for her husband describes how she relies on both groups to navigate to the information she needs: “We have found that we get helpful info from both doctors and other patients/caregivers. Other patients/caregivers are almost more helpful when it comes to this disease because as a group they have more info than any one individual doctor has. We have gotten info from other patients/caregivers that we’ve then told the oncologist about so he could look into it. Sometimes we feel like we’re educating our doctor more than he is educating us.”

One mother of a now-adult child with a rare condition wrote about how much she values the advocacy group founded by a group of patients. She writes, “Experts who have superior information than the best hepatologists are there to answer our questions. Patients and caregivers are there for each other and no question remains unanswered. I wish we had had this group of 2,000 with us at the beginning.”

A mother of a small child with a rare condition writes about the lifeline she has found online: “When a disease is so rare and there are no folks in your town, and few in your state who are going through what you are going through, you need a support group that encompasses people from all over the world. Getting to know people through the disorder has been an amazing experience and has created incredibly wonderful friendships and ties.”

Health professionals retain their role as experts in a certain field or condition, but in these disease communities, each person is an expert in observing the effects of a disease or a treatment on their own or a loved one’s body or mind. In this way, rare-disease patients and caregivers who gather together online are an example of a “smart” group, the elements of which James Surowiecki described in his book, The Wisdom of Crowds: They are diverse and decentralized, yet able to pool knowledge and summarize their observations, no matter how eccentric or individual they may be.9

Our findings also echo what has been found in other research. A 2007 study of the Association of Cancer Online Resources found that information exchange, not simply emotional support, was the primary driver for community members. Indeed, “the most common expressions of support were offers of technical information and explicit advice about how to communicate with health care providers.”10 PatientsLikeMe, an online quantitative personal research platform for patients, has published several studies noting the benefits gained by people who share personal health data and tips about their conditions.11 In one 2010 study, “patients reported making more informed treatment decisions as a result of using the site, particularly around managing side effects.”12 CureTogether is another example of using patient-contributed data to crowd-source answers to health questions on a wide range of topics.13