Background

Since the mid-1990s when the World Wide Web became a powerful part of America’s communications and information culture, there has been great concern that the nation’s racial minorities would be further disadvantaged because Internet access was not spreading as quickly in the African-American community as it was in the white community. Former Assistant Secretary of Commerce Larry Irving said in his introduction to “Falling Through the Net,” the 1999 Department of Commerce Study on the digital divide, that this issue “is now one of America’s leading economic and civil rights issues.”1 Analysts like Irving argued that African-Americans would be at a distinct disadvantage if the divide were not closed because more and more of American economic and social life was becoming networked through the Internet.

Many studies have shown that access to the Internet correlates with income levels and educational attainment. African-Americans lag behind whites in both areas. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the median household income for African-Americans in 1999 was $27,910, while the median income of white Americans was $42,504. The Census also reported in 1999 that 15% of African-Americans have received a college or a graduate degree. This is less than the 26% of white Americans who have gotten degrees. Our recent report entitled “Who’s Not Online,” showed that a person living in a household with more than $75,000 in income is three times more likely to have Internet access than someone in a household earning less than $30,000. Beyond socio-economic issues, some researchers have theorized that African-Americans have had less access to the Internet because they participate in greater measure in entertainment-oriented technologies like television, rather than in information technologies. They argue that relatively high proportions of African-Americans use radio and television, but a relatively low proportion of African-Americans read newspapers.2

Narrowing the gap

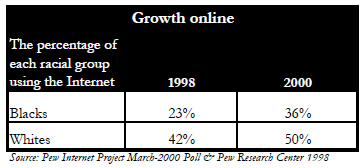

Much has changed in the last year, and data collected by the Pew Internet & American Life Project reveal that the digital divide for African-Americans is narrowing. A 1998 Pew Research Center for the People and the Press report found that 23% of African-Americans and 42% of white Americans had Internet access. Over the past two years, the rate of growth of the African-American online population has been a bit greater than that of whites. In 2000, the percentage of the black adults who have Internet access grew 13 points to 36%; for whites, the online population grew 8 percentage points to a level where half of all white adults now have Internet access.

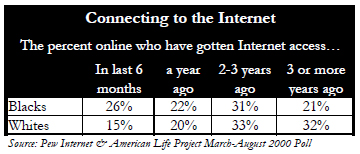

In the past year, more than 3.5 million African-Americans have gone online for the first time. Almost half (48%) of all African-American Internet users say they got access to the Web for the first time in the past twelve months; just over a quarter (26%) first accessed the Internet in the past six months. The overall African-American population online is about 7.5 million, more than 4 million of whom are women.

Women are leading this surge – they represent 61% of the African-American Internet newcomers. This mirrors the general trend we first reported in May that women of all races predominate among Internet newcomers. In just the past six months, about 1.2 million African-American women accessed the Internet for the first time, compared to approximately 750,000 African-American men.

That has opened up a notable gender gap in the black online population and this represents a different situation from the one that has taken place in the online white population. Among white Internet users there is an even split between the sexes. Yet black women make up 56% of the African-American online population.

Despite this substantial growth, African-Americans still lag behind their white counterparts in Internet access and computer use. Some 36% of African-Americans have ever used the Internet, as opposed to about half of all whites. A little over half of all African-Americans use computers, while 63% of whites use computers. Rural blacks are not nearly as connected to the Internet as blacks who live in cities or suburbs. Just 22% of blacks in rural areas have online access, compared to 41% of suburban blacks who have access and 35% of urban blacks.

Portrait of the newcomers and the general African-American online population

The boost in connectivity by African-Americans tracks general patterns among newcomers to the Internet. The increase in women online is a major part of that story, and so are the facts that the novices are older than those who got Internet access several years ago; the beginners have less educational attainment; and their income is as not as high as their Internet forbears.

- In the past year, more than 2 million blacks over the age of 30 accessed the Internet for the first time. This represents 55% of all blacks who first came online in this period.

- During the same period, 55% of the African-Americans who accessed the Internet for the first time do not possess a college diploma.

- And 62% of blacks who entered the online world in the past year have incomes of under $40,000 a year.

In its general composition, the online African-American population is different from the white online population in several major respects. Compared to whites with Internet access, the online African-American population is proportionally more composed of women, of people who have modest incomes, and of people who do not have college degrees.

Of the African-Americans who use the Internet, 43% live in households with incomes under $40,000 a year. About a quarter live in households with incomes between $40,000 and $75,000 and 15% are in households earning more than $75,000. In contrast, 29% of online whites live in households earning under $40,000 a year, 30% live in households earning between $40,000 and $75,000 and 23% live in households earning more than $75,000.

When it comes to educational attainment, 27% of online blacks have a college or graduate degree, compared to 38% of online whites who possess a college diploma or better. About 37% of online blacks have some college experience, compared with 30% of online whites. A similar proportion (28%) of online blacks and whites possess high school degrees.

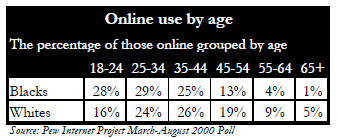

The online African-American population is still fairly young – 56% of online blacks are under the age of 34. In comparison, about 40% of online whites are in that age bracket. The online white population is older. About half the online whites (46%) are between the ages of 35 and 54 and 14% of online whites are over 54. That contrasts with the fact that 38% of online blacks are between 35 and 54 and just 5% of online blacks are older than that. While the Internet is starting to appeal to older Americans, older blacks still have a way to go in getting connected to the Web at the same rate as their white counterparts.

One other striking demographic feature of the African-American online population is that there are a lot of parents with children under 18. About 53% of online blacks have a child under the age of 18 at home, while 42% of online whites are parents of children that age. Users often perceive gaining access to the Internet as an investment in the future and this seems especially true in African-American families.

African-Americans’ online behavior

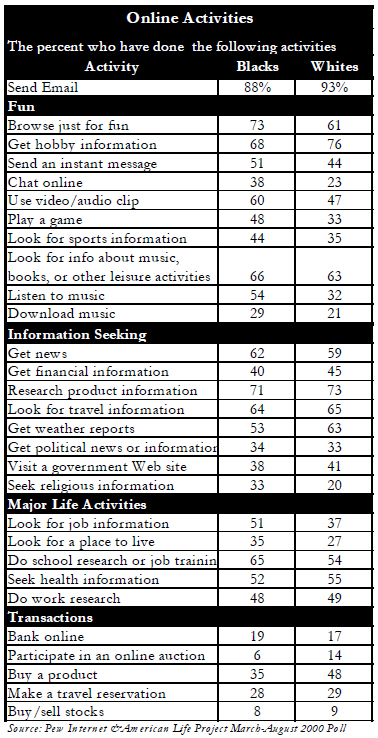

Online blacks are comparatively more likely than whites to have used the Internet for activities that relate to economic advancement and significant quality-of-life issues. More than half of online African-Americans (51%) have used the Internet to get information about a job, compared to 37% of whites who have done that. More than a third of African-Americans (35%) have used the Web to hunt for a place to live, compared to 27% of whites. Online blacks are also more likely than online whites to have used the Internet for school-related research or job training.

African-Americans also have sampled some the entertainment features of the Internet relatively more than whites. Fully 73% of blacks have gone online “just for fun,” compared to 61% of whites who have done the same. Blacks are more likely than whites to have used Internet multimedia – 60% have looked at or listened to a video or audio clip while online; 48% have played a game online; and 29% have downloaded music from the Web.

When it comes to the general hunt for information on the Web, the behavior of online whites and African-Americans is relatively similar. Both groups have used the Web in similar proportions to get general news and news about politics, to research product information and travel-related information, to get material from Web sites run by federal, state or local government agencies, get health information, and do work-related research. Online whites are slightly more likely than online African-Americans to have sought financial information online and to have checked out weather reports.

The one striking difference between the races related to online information gathering comes in the area of religious and spiritual material. Online blacks are 65% more likely to have sought such material on the Web than online whites. Some 33% of online blacks have hunted for such information online, while just 20% of whites have done it. This is a particularly popular activity with African-American women over age 30.

Online transactions are a somewhat different story. Online whites are more than twice as likely as online blacks to have participated in Web-based auctions and whites are much more likely to have bought products on the Internet. However, both races are equally as likely to have done banking online, made a travel reservation, and bought or sold stocks.

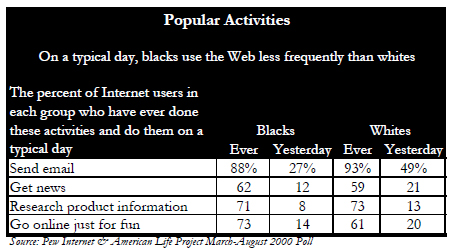

A typical day online

While African-Americans are rapidly entering the online world, it is apparent that the Internet has not yet become as essential or appealing to the black online population as it is to online whites. Just 36% of blacks with Internet access go online on a typical day. By comparison, 56% of whites with Internet access are online on an average day. On the whole, online African-Americans also are not as fervent in their appreciation of the Internet as online whites. While 73% of online whites say they would miss the Internet if they could no longer access it, 62% of online blacks say the same thing. Even more telling is that while 10% of online whites say they wouldn’t miss the Internet at all if they were to lose access, 20% of online blacks say they wouldn’t feel any loss. Half of all white Internet users would miss email a lot if they could no longer use it, but only 39% of black users agreed.

These different attitudes could partly be explained by the “experience gap” between the races. As a rule, newcomers of all groups, ages, income brackets, and genders use the Internet less frequently than online veterans and feel less attached to the Internet. Like other Internet newcomers, online African-Americans have not integrated many online activities into their daily lives. In comparison, a greater share of the online white population has extensive experience with the Internet and has woven Internet activities into their lives.

Further evidence that the Internet has not become quite as ingrained in black users’ lives as white users’ lives comes in examining daily use of the Internet. For example, the use of email is the most popular of all Internet activities, and about 88% of all black Internet users have sent email. However, only about 27% of blacks with Internet access send or receive email on a typical day. In contrast, almost half of online whites (49%) send or receive email on a typical day.

This pattern of relatively low daily use of Internet activities also applies to some other major online activities that have been measured by the Pew Internet & American Life Project. On an average day, online whites are more likely than online blacks to get news, get financial information, get product information, and browse for fun.

Where African-Americans have access and the time they spend online

African-Americans Internet users are somewhat more likely than whites to have their Internet access come exclusively through their jobs. Some 18% of African-American Internet users only have access to the Web at work, while 12% of white users are in that position. In contrast, white Internet users are more likely than African-Americans to have access at home. Some 71% of black Internet users have access to the Web from home, while 84% of white users have home access.

This difference in access arrangements might account for some differences in online behavior – for instance, why whites are more likely to transact personal business online such as purchasing goods, and why blacks are more likely to have gone online for some information-oriented activities, such as looking for a job or a place to live. In addition, workplace computers are more likely to have higher bandwidth connections, thus making the use of online multimedia relatively easier for African-Americans. Finally, since African-Americans are newer to the Internet and many are going online from computers at work, they may also enjoy the benefit of having more powerful multimedia computers than whites who have been online for longer.

While online during a typical day, African-American Internet users tend to mirror their white counterparts in the amount of time they spend online and the times of day they are online. Between 9 a.m. and 5 p.m. a fifth to a quarter of the Internet users in each race are online. However, during non-working hours, blacks are less likely to go online than whites. In the early morning before nine, 19% of black users go online, while a quarter of white users do so. After 9 p.m. 17% of online whites log on, while 12% of online blacks log on.

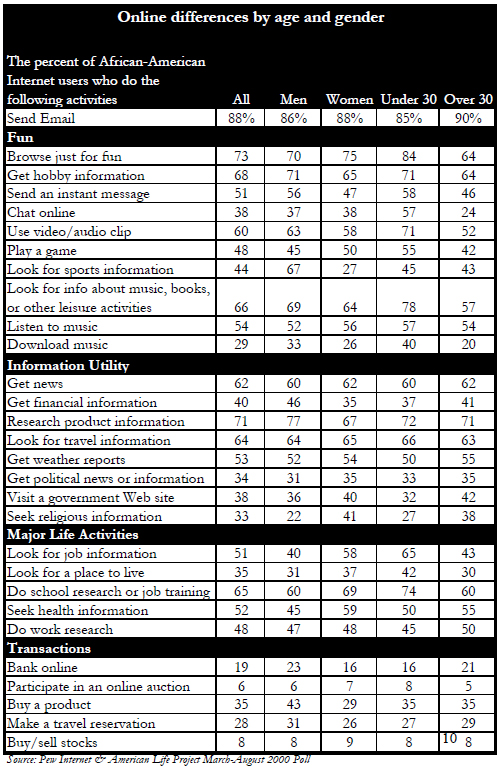

Online differences by age and gender

Gender gaps

In the African-American Internet population there are some notable variations that generally reflect the gender differences in the overall Internet population.

Compared to African-American men, African-American women are much more likely to have gotten health information online, looked on the Web for job information, and sought spiritual or religious material online. Fully 59% of online black women have sought information on health and medical issues, compared to 45% of black men who have done that. A strong majority of black women (58%) have used the Internet to seek information about a new job, compared to 40% of black men who have done that. And four in 10 black women (41%) have sought religious and spiritual information on the Internet, almost twice the level of black men who have done that (22%).

African-American men, on the other hand, are more likely than women to have used the Web to seek financial data, purchase goods, and get sports information. Almost half the black men who have Internet access (46%) have used the Web to get information on stocks, mortgages, and other financial products, compared to 35% of black women who have done that. Some 43% of online black men have purchased something online, compared to just 29% of black women who have done that. And two-thirds of black men have used the Web to get sports information, while only 27% of black women have done that.

Generation gaps

Younger blacks are drawn to leisure activities on the Internet to a much stronger degree than their older counterparts and they are more likely to use the Web for research on life changes. On the other hand, older African-Americans are more inclined to access government agency Web sites and seek spiritual information.

Fully 84% of black Internet users under 30 have browsed the Web for no particular reason except to have fun, compared to 64% of older blacks who have done that. More than half of young black Internet users (57%) have participated in chat rooms, while only 24% of their elders have done so. Some 55% of young black Internet users have gone online to play a game, while 42% of older black users have done that. Forty percent of young online blacks have downloaded music, and 71% of them have listened or watched a multimedia clip. At the same time, only 20% of older blacks have downloaded music and 52% have seen or heard online multimedia. Finally, 65% of young users have sought job information on the Web and 42% have sought information on a place to live. That compares to 43% of older blacks who have used the Internet to look for a job, and 30% have used the Internet to look for a new home.

Some 42% of older online blacks have sought information from Web sites run by their local, state and federal government, compared to 32% of younger blacks who have done that. And 38% of older blacks have sought religious or spiritual information online, while 27% of younger online African-Americans have done that.

Experience makes a difference

As Internet users become more and more comfortable using the Web, they are more likely to expand their access and time online, to branch out to different Web activities, to access Web activities more often, and stay online longer. African-American users follow these patterns.

African-American Internet veterans with more than two years experience are more likely than newcomers to go online on a typical day, more likely to spend three or more hours online during a typical day, and more likely to have access at home and work.

Black Internet users with several years experience are substantially more likely than novices to send and receive email, get news online, get product and financial information (such as stock prices and mortgage rates), look for job information, seek material on places to live, buy products, do banking online, do job-related research, get hobby information, and get information from government Web sites. These veterans are also more likely than novices to report that Internet tools have helped them manage their finances better, to connect to their family and friends, to learn new things, and to do their jobs.

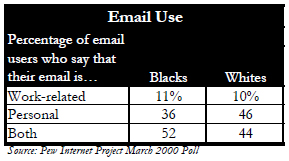

How African-Americans use email

Using email is the Internet’s most popular activity for everyone. Some 88% of all black Internet users have sent or received an email. Some 93% of white Internet users send and receive email.

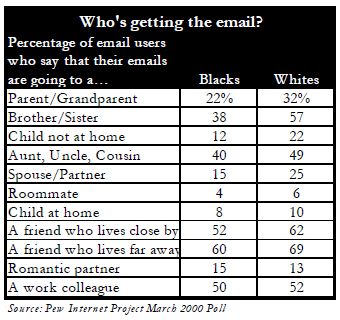

One of the attractions of email for Internet users is its power to strengthen relationships with family members and friends. Fully 89% of African-Americans who go online have emailed a member of their family. And these African-American emailers feel strongly about the positive effects of doing so; 92% of African-American emailers who exchange email with their kin say that email has been useful for communicating with members of their family. More than half of African-American email users (56%) who have an email relationship with a key family member believe the use of email has helped them communicate more often with that family member. This is similar to the proportion of whites who feel that way.

This increased communication with family members can be ascribed to a number of reasons. It is the ease and quickness of email that attracts black Internet users – African-Americans most often cited that as the primary reason for using email to communicate with a family member. Whites, on the other hand, more often say the primary reason for sending email to a family member is that it can be done at the sender’s leisure. African-Americans also like the fact that their use of email means that they do not have to talk as much to family members – 72% of African-American emailers say this, compared to 62% of white emailers.

Emailing friends is also a common activity among online African-Americans – 69% of them say they have done so. However, this is proportionally less than the 80% of white users who email their friends. While they may email their friends less than their white counterparts, African-American users strongly believe that the email is a useful tool for communicating with their friends. Fully 89% of black users say this, and 90% of white users agree. Emailing friends has not made as strong an inroad into black Internet users’ behavior as emailing family members. About 44% of black users who have an email tie to a key friend say they communicate more often with that friend because of email, while 65% of white users are communicating more because of email.

African-American emailers do not use email as much as their white counterparts to communicate with their immediate family. While 32% of white emailers have sent a message to their parents or grandparents, only 22% of black users have done so; over half (57%) of white users have sent a message to a sibling, but only 38% of black users have emailed a brother or sister. More white emailers have also used email to communicate with extended family – 49% have ever emailed an aunt, uncle or cousin, while 40% of black email users have done so.

However, African-American emailers have used email to communicate with other important people in their lives outside of their family at about the same rate as their white counterparts. Many African-American emailers use email to communicate with friends near and far (52% and 60%). White emailers do much the same thing, but at somewhat greater frequency (62% and 69%). African-American email users have also emailed romantic partners and people with who they work at about the same rate as white users.

African-American views of the Internet

Like those in other groups, many African-Americans have found that access to the Internet has helped them in key parts of their lives. Just over half (51%) say that the use of email has improved their connections to family members; about 55% say that the email and the Internet has also improved connections to their friends. These sentiments echo an earlier Pew Internet Project study that found that a little over half of all Internet users say that the use of email has encouraged and improved communications with both their family and their friends.

Black women express appreciation for email’s benefits more frequently than black men. About 56% of African-American women who use the Internet say that the use of email has strengthened their intra-family connections. About 37% say that email has improved communication with family members a lot. On the other hand, only 43% of black men view email as having had a positive impact on their familial relationships; only 20% say that email has improved these relationships a lot. These feelings reflect a pattern that is evident among white Internet users: 61% of white women, but only 50% of white men, agree that email and the Internet has improved their relationships with their family.

At the same time, a little over half of all online blacks agree that the Internet and email have helped them in their connections with friends. However, online whites are somewhat more likely to say that than online blacks.

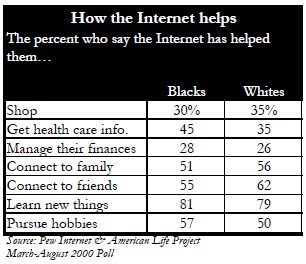

African-Americans also agree that the Internet has improved their lives in other aspects as well, at about the same rate as whites. One exception is that online blacks are more likely than online whites to report that the Internet has become a significant source of health care information for them. About 45% of blacks agree that the Internet has helped them find health care information, as compared to a little over a third of whites. Women are more likely to say this than men. There is also a bit of a gap when it comes to hobbies. Online blacks are more likely than online whites to say the Internet helps them pursue their hobbies (57%-to-50%). Men are much more inclined than women to say this.

African-Americans and Online Privacy

Online privacy has become a significant concern for a majority of Internet users, African-Americans included. In fact, African-Americans tend to be less trusting than their white counterparts, as well as more concerned about their online privacy. A recent survey of people’s attitudes towards trust and privacy by the Pew Internet Project found that only 17% of all African-Americans (Internet users and nonusers alike) believe that most people can be trusted, compared to 34% of whites who say that. On the flip side, 79% of blacks say that one cannot be too careful in dealing with other people, compared to 59% of whites who agree. At the same time, 72% of black Americans are very concerned about businesses and other people obtaining their personal information. Fifty-seven percent of whites are similarly worried.

African-Americans’ heightened privacy concerns are reflected in what they choose to do online. Online African-Americans are less likely to participate in high-trust activities like auctions or to trust their credit card to an online vendor. They are also less likely than white Internet users to trade their personal information for access to a Web site. But African-American Internet users don’t shy away from the convenience of banking, making travel arrangements, or trading stocks online. And black Internet users are more likely than white Internet users to have made a friend online. These leaps of faith reflect mixed emotions that are common among all Internet users – they are fearful of the risks, but still want to take advantage of much of the Net’s potential.