Introduction and background

By the staff of the Pew Internet & American Life Project

The September 11 terror attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon were the most seismic news events in the Web era. They dominated people’s thoughts and their actions online like no other event before them.

One of the most important and potentially long-term impacts of the 9/11events and their aftermath is how they compelled government officials and ordinary Americans to consider what kinds of information should be made available online. As a rule, and in many cases by the dictates of law, much of the information that government collects about American manufacturers, utilities, and transportation firms is made public. But after 9/11, the creators of various government Web sites chose to remove sensitive information that could potentially be useful to terrorists. This included information such as emergency response plans for chemical plants, GIS data, detailed maps and descriptions of nuclear facilities, reports on chemical transportation security, and information on water supplies. According to information gathered by OMB (Office of Management and Budget) Watch, a non-profit that promotes government accountability (www.ombwatch.org), 13 government agencies and three state Web sites have prevented access to information that was previously available to the public online:

- The Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry—removed a report on security at chemical plants

- Bureau of Transportation Statistics—most Geographic Information Services were made unavailable

- Department of Energy—removed various maps, reports, Web sites, databases relating to nuclear facilities or liquefied gas fuel dangers

- Department of Transportation—discontinued access to the National Pipeline Mapping System

- Environmental Protection Agency—restricted access to Web sites, Envirofacts databases, emergency chemical exposure guidelines and assessments, risk management plans, facility floor plans and maps

- The Federal Aviation Administration—removed the Enforcement Information System database

- The Federal Energy Regulatory Commission—made specifications on energy facilities unavailable

- Internal Revenue Service—removed page that contained information for IRS employees displaced as a result of 9/11

- The National Archives and Records Administration—discontinued access to some archival materials

- NASA Glenn Research Center—restricted public access to its website

- The National Imagery and Mapping Agency—stopped the sale of large-scale digital maps as well as the downloading of maps from its archives

- The Nuclear Regulatory Commission—took down its Web site

- The U.S. Geological Survey—removed multiple reports on water resources

- The State of Florida—prevented access to information on crop dusters and certain driver’s license information

- The State of New Jersey—removed chemical storage information

- The State of Pennsylvania1—withheld certain environmental information

In addition, The Washington Post reported on October 4, 2001 that the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, housed under the Department of Health and Human Services, removed a report on chemical terrorism from their Web site.2

These actions coincided with a memorandum issued on October 12, 2001 by the Attorney General, John Ashcroft, that urged federal departments and agencies to “carefully consider” the disclosure of sensitive information under the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) and assured them that any decisions to withhold records would be defended by the Department of Justice unless they “lack a sound legal basis.”3 Such exemptions from the FOIA were also encouraged in a memo issued by White House Chief of Staff, Andrew Card, on March 19, 2002, that called for an immediate re-evaluation of any classified, reclassified, declassified or “sensitive but unclassified” material whose disclosure could prove to be harmful.4

In some cases, these assessments resulted in the removal of isolated documents; in others, it meant shutting down entire Web sites. The U.S. Geological survey, for example, pulled several reports on water resources from its Web site, while the Web site for the National Transportation of Radioactive Materials at the Department of Energy was completely removed.5 Although some information on agency Web sites was only removed temporarily, much information has remained restricted.

Our survey from June 26 to July 26, 2002 found that just 25% of the public (28% of Internet users) were aware that government agencies had pulled information from Web sites. And only 5% of Internet users said they had noticed that information they expected to be on a government Web site was missing. Nonetheless, Americans have definite views about what government agencies should and should not do with sensitive information on their Web sites.

Americans’ views about what government agencies should post online

Citizens are willing to give their government wide leeway in deciding what information to provide on agency Web sites if officials argue that information might be useful to terrorists. More than two-thirds (69%) say the government should do everything it can to keep information out of terrorists’ hands, even if that means the public will be deprived of information it needs or wants. A quarter of Americans believe otherwise: 24% say Americans have a right to information from their own government even if that information could be helpful to terrorists. Following from that, 67% of Americans believe the government should remove information from its Web sites that might potentially help terrorists, even if the public has a right to know that information. Similarly, two-thirds of Americans believe businesses and utilities should not put information that might help terrorists on their Web sites.

Yet even as they express a willingness to cede power over what to disclose to government officials, a distinct plurality of Americans believe that taking government information off the Internet will not make a difference in battling terrorists. Some 47% say that the act of withholding or removing information from government Web sites will not make a difference in deterring terrorists; 41% say that taking information off government Web sites will hinder terrorists. Some 12% of Americans are uncertain whether those acts will help or not.

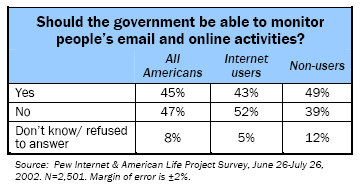

Citizens are sharply and evenly divided on the question of whether the government should be able to monitor people’s email and online activities. By a 47%-45% margin, Americans believe the government should not have the right to monitor people’s Internet use. There was a distinct split between Internet users and non-users in answering that question. Internet users opposed such monitoring by a 9-point margin, and non-users supported the idea of government monitoring by a 10-point margin.

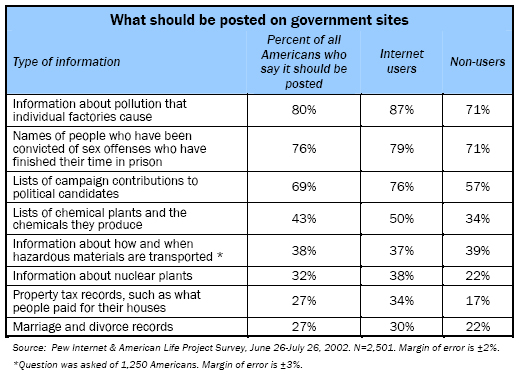

In general, Americans have different views about the value of different kinds of information on government Web sites. They generally support the idea of the government providing information about clearcut, immediate threats – for instance, pollution and sex offenders – and about information that is important to the political process such as campaign contributions. But they are much more wary of the government providing information that seems personal (property tax records, marriage and divorce records) or that might aid people who are planning to do harm.

We pressed those who favored disclosure about some kinds of information whether their views would change if the government argued that this information could help terrorists. Many then supported the idea that such information should be removed from the Internet:

- 60% of those who originally believed the government should post information about chemical plants and the chemicals they produce said that material should be removed from the Internet if the government said it could help terrorists.

- 55% of those who originally believed the government should post information about nuclear plants said that material should be removed from the Internet if the government said it could help terrorists.

- 54% of those who originally believed the government should post information about the pollution caused by individual factories said that material should be removed from the Internet if the government said it could help terrorists.

The difference when information relates close to home

We asked some of our respondents whether it would be a good thing or a bad thing to have information posted on the Internet about how and when hazardous materials are transported through their communities. By a nearly 3-2 margin (57%-34%) they said it would be a good thing to post such material and there was very little difference in the beliefs of Internet users and non-users.

However, those who generally think such material is important to their community and belongs online relinquish that position if the government makes the case that terrorists might be aided. Some 58% of those who originally believed the government should post information about the transportation of hazardous materials through their community say that material should be removed from the Internet if the government said it could help terrorists.

What Internet users have changed in their online behavior

The attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon have influenced the way that some people use the Internet to communicate with others and to gather information from key online resources.

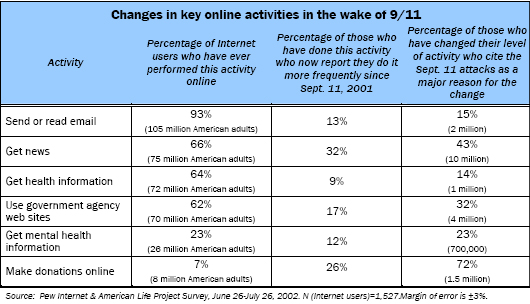

Overall, modest but notable numbers of Internet users say they are using email more often, gathering news online more often, seeking online health information and mental health information more often, visiting government Web sites more frequently, and making online donations more often, at least in part as a response to events of 9/11. For some Americans, the attacks were a major reason for their changed online behavior – especially by groups who say they are getting more news online, going to government Web sites more often, and making more online donations. For others, the attacks were a minor reason for their changed behavior – that is particularly true for those seeking health information.

These patterns of increased Internet use in some activities also reflect broader trends we have seen in online behavior we have charted separately and apart from 9/11. Our July 2002 survey shows increases in most of these online activities, compared to survey data gathered last fall.

19 million used email to re-establish relations with family members, old friends, and colleagues

The September 11 crisis spurred a significant number of Internet users to reconnect with old friends, family members, and colleagues from their past. One in six email users (17%) report that in the weeks after the terror attacks they sent an email to someone with whom they had not been in contact for several years. That amounts to 19 million American adults who used email to reestablish connection with someone important from their past. And the vast majority (83%) of those who reached out have maintained their ties to those long-lost companions from their past.

Online women were 40% more likely than men to have reached out via email to long-lost friends, family, and former colleagues. And the heaviest Internet users, those who are online daily, were more likely than less fervent Internet users to have used email to track down companions from their past.

The impact of 9/11 on overall Internet use

A small fraction of Internet users (2%) say the amount of time they go online has been directly affected in a major way by the 9/11 attacks and they are evenly divided between those who say the attacks have prompted them to go online more and those who say the attacks have provoked them to go online less.

Since the attacks, about 8 million more Americans have gone online for the first time and the overall number of adult Americans who use the Internet has grown to 113 million.

Life is “far from normal” for 11% of Americans

Many Americans, both Internet users and non-users alike, think the country suffered a grievous blow on September 11. Virtually half the nation (49%) thinks the country has changed a great deal since the attacks and another 34% say the country has changed some. At a personal level, 17% of Americans say their own life has changed a great deal since the attacks, and another 33% say their own life changed some. In sum, half of Americans say their own lives were changed a year ago at least to some noticeable degree.

The majority of those who say their own lives were dramatically affected at the time of the attacks are still coping with the change. In all, 11% of Americans say that life is still far from normal since the 9/11 attacks. Of that group, half use the Internet.

Compared to other Internet users, these hard-hit Americans are more likely than other Internet users to have used email, instant messaging, and Web sites to connect to their family, their friends. Hard-hit Americans are also more likely than other groups to say email should be monitored if it would prevent future terrorist attacks.

Americans who say life is far from normal are more likely to be older than those who say life is back to normal. African-Americans are 70% more likely than whites to report that life has not gotten back to normal for them, and Hispanics are 40% more likely to report a significant long-term impact on themselves than whites are. Hard-hit Americans – Internet users and non-users alike – are more likely to live in an urban area and in the South than those who say life is back to normal. Otherwise, they reflect the overall population – half of these hard-hit respondents are men and half are women. They are no more likely than other respondents to be living in wealthy or poor households, to be Democrats or Republicans, or to be employed or unemployed.

The hard-hit respondents who go online are more intense in their use of some key communication tools. Internet users who say life is far from normal are more likely to use the Internet on a typical day (60%, compared to 53% of those whose lives are back to normal) and more likely to send email on a typical day (55%, compared to 47% of those whose lives are back to normal). They are also more likely to say that they email more frequently since the 9/11 attacks and that the events are a reason for this increased activity.

In the days following 9/11, 30% of hard-hit Internet users sent email to people they had not been in contact with for several years, compared to 14% of Internet users who say life is back to normal. Of those who sent emails last September, 90% of hard-hit respondents say they are still in touch with those people through email or in other ways, compared to 79% of respondents who say life is back to normal.

Hard-hit Americans are more likely than other groups to say they plan to take part in almost every form of 9/11 remembrance – watching television specials, going to services, reading special magazine or newspaper issues. Their desire to fly the American flag is equaled by other groups. Hard-hit Americans with Internet access are more likely than other groups to say they plan to email family and friends, visit Web sites devoted to 9/11, and to read and exchange thoughts with other people online.

Those who say life is far from normal are more likely than others to back government decisions to remove information from the Internet. And 52% of hard-hit Americans think the government should monitor email to prevent terrorism, compared to 43% of those who say their lives are back to normal (and 45% of all Americans).

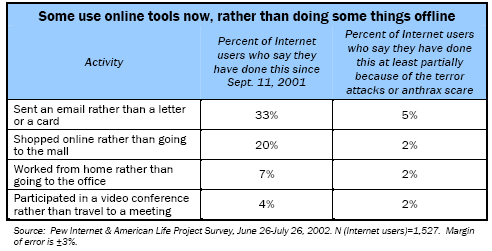

Some Internet users now do things online instead of performing offline activities

About a tenth of Internet users say they have started doing some things online that they would have done offline before the terror attacks occurred. The list is compiled in the table below:

How Americans plan to commemorate 9/11

The first anniversary of the terror attacks will be a national time of mourning, solemn patriotism, and policy debate. Virtually every American plans to do something to remember the events of 9/11, honor the victims, and/or pay tribute to those involved in the rescue and recovery work. Some plan to perform acts of civic participation, too.

Asked about several possible activities they could perform on the first anniversary of the attacks, Internet users say they are very likely to do something, but their remembrance activities are more likely to be things they do offline than things they do online. Here are the things U.S. Internet users say they are very likely to do in the days surrounding the anniversary:

- 70% of Internet users say they will fly the American flag at home or work

- 44% of Internet users say they will watch television specials about 9/11

- 35% of Internet users say they will read special issues of magazines or newspapers related to 9/11

- 25% of Internet users say they will attend religious services, community services, or memorials related to 9/11

- 22% of Internet users say they will send email to friends or family about 9/11

- 12% of Internet users say they will visit commemorative Web sites

- 10% of Internet users say they will go to Web sites to read others’ opinions on the anniversary

- 5% of Internet users say they will post their own thoughts about the anniversary on a Web site bulletin board, in a chat room, or on an email listserv

Methodology

This report is based on the findings of a daily tracking survey on Americans’ use of the Internet. The results in this report are based on data from telephone interviews conducted by Princeton Survey Research Associates between June 26 and July 26, 2002, among a sample of 2,501 adults, 18 and older. For results based on the total sample, one can say with 95% confidence that the error attributable to sampling and other random effects is plus or minus 2 percentage points. For results based on Internet users (n=1,527), the margin of sampling error is plus or minus 3 percentage points. In addition to sampling error, question wording and practical difficulties in conducting telephone surveys may introduce some error or bias into the findings of opinion polls.

The sample for this survey is a random digit sample of telephone numbers selected from telephone exchanges in the continental United States. The random digit aspect of the sample is used to avoid “listing” bias and provides representation of both listed and unlisted numbers (including not-yet-listed numbers). The design of the sample achieves this representation by random generation of the last two digits of telephone numbers selected on the basis of their area code, telephone exchange, and bank number.

New sample was released daily and was kept in the field for at least five days. This ensures that complete call procedures were followed for the entire sample. Additionally, the sample was released in replicates to make sure that the telephone numbers called are distributed appropriately across regions of the country. At least 10 attempts were made to complete an interview at every household in the sample. The calls were staggered over times of day and days of the week to maximize the chances of making contact with a potential respondent. Interview refusals were recontacted at least once in order to try again to complete an interview. All interviews completed on any given day were considered to be the final sample for that day. The response rate on this survey was 38%.

Non-response in telephone interviews produces some known biases in survey-derived estimates because participation tends to vary for different subgroups of the population, and these subgroups are likely to vary also on questions of substantive interest. In order to compensate for these known biases, the sample data are weighted by form in analysis. The demographic weighting parameters are derived from a special analysis of the most recently available Census Bureau’s Current Population Survey (March 2001). This analysis produces population parameters for the demographic characteristics of adults age 18 or older, living in households that contain a telephone. These parameters are then compared with the sample characteristics to construct sample weights. The weights are derived using an iterative technique that simultaneously balances the distribution of all weighting parameters.