Communicating with citizens

Eighty-two percent of online local officials use email to communicate with citizens. Sixty percent do so at least weekly, and 21% do so every day. Those in larger cities tend to email citizens more frequently. Almost half (49%) of online officials in cities over 150,000 email citizens daily, while only 9% of those in cities with populations under 20,000 do so.

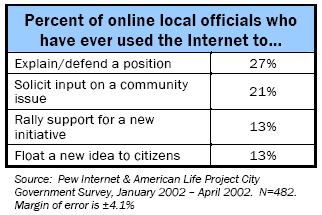

In their communications with constituents, 21% have used email to solicit input on a community issue, and 13% have sought to float a new idea to residents.

Online local officials appear to receive slightly more email than they send. Some 74% of these respondents say they receive email from citizen groups at least weekly, and 24% saying they receive it every day. Not surprisingly, those who receive email the most frequently tend to be the same people who send it most frequently; we see little evidence of officials sending email to the community and getting nothing in return, or of officials who do not use email being pummeled with electronic messages from constituents.

In addition to individual messages exchanged between citizens and officials, some communities have set up group listservs where residents and officials alike can discuss local issues in an informal, coffeehouse type manner. Participation is relatively rare among online officials, at about 17%. And half of those participate only tangentially – they have others monitor the listservs and keep them informed. The remainder is equally divided between those who read the listservs but do not post, and those who actively participate.

Contact with colleagues

Seventy-eight percent of officials use email to communicate with their colleagues. A small group, about 8%, of online officials use email exclusively for intra-governmental communications, and never email citizens at all. Officials email their colleagues with the same frequency across cities, regardless of population.

Local officials combine public and private Internet accounts to suit their own schedules and needs

Although the majority of online officials receive Internet access and email through their cities, only 30% rely on those accounts alone for their official duties. Some 37% rely on both government and personal accounts, and 33% rely on personal accounts exclusively.

Larger cities, with their correspondingly larger budgets, are more likely to provide local officials with the resources needed to rely on government accounts exclusively. While only 19% of online officials from cities with of under 20,000 use government accounts exclusively for their duties, 42% in cities of over 150,000 do so. Online officials in the smallest cities are more likely to rely exclusively on their personal accounts: 37% vs. 23% for larger cities. (Those who make use of both official and personal accounts appear in all cities, regardless of size.)

Thus, it is not surprising that nearly 2 in 5 (38%) online officials report using more than one email address in the course of their official duties. It appears that many of these individuals are part-time citizen-legislators who support themselves with full time jobs. Many do not have regular “office hours” (or even offices), so they provide constituents with their business or personal email addresses in order to be available throughout the day. One official noted that government email accounts could not be reached outside government offices, and many others said that it was generally easier to deal with official email at home. A few even noted that their personal accounts simply worked better than their official accounts. For example, one official complained that the city account did not provide a spell check feature for email.

Others cited reasons that reflect the reality of living among constituents. One official continues to respond to constituents on his pre-election email address, presumably one that those constituents already have in their in their electronic address books.

FOIA and email

Another issue that injects itself in the official/personal email account management is the tension between Freedom Of Information Act (FOIA) laws and privacy rights.

FOIA laws, often called “sunshine laws” serve to promote honesty in government. It is much harder to do official business out of the public eye, make secret deals or even cover up illegal activities if documents are preserved and available to the public. Nonetheless, public documents contain a considerable amount of private information about individual citizens. Government has recognized certain privacy rights that cannot be violated in the name of FOIA. Tax returns, for example, are generally exempt from FOIA due to the extensive personal information contained in them.

Still, the matter of privacy vs. FOIA is rarely as clear-cut as in the case of tax returns, and the introduction of the Internet into the public sphere has increased the complexity of the issue further. The Internet can make public records “too public.” Records kept in a county courthouse contain significant amounts of personal information relating from everything from child support payments to psychological evaluations. Theoretically, anyone can look at them. But as a practical matter, the availability of such records in bulky paper files that are accessible only during working hours generally keeps that information private. Put all those records on the Internet, and people can check up on their neighbors, customers or employees on a whim. Concerns such as these are leading some states to introduce legislation shielding some public information from online disclosure.

Many people send emails as casually as they place a phone call. But phone calls are ephemeral and irretrievable (unless, of course, there is a wiretap), while emails become their own record. Many laws recognize email from and to public officials as public record.

Just over half (53%) of online local officials responding in our survey say that their email is subject to FOIA disclosure. Of those, about one third (34%) have received FOIA requests for their email from the press or citizen groups. Officials in cities with populations over 150,000 were almost twice as likely (60%) to have been asked to turn over some of their email. Thirty-seven percent of online local officials say they do not know if their email is subject to FOIA (although one wrote “But it should be.”). Those who use email every day are the most likely (60%) to say that their email is subject to FOIA, while those who “never” email are the most likely (55%) to say they don’t know.

The nature of the work of the citizen-legislator makes email perhaps the most viable communication tool and that may leave citizens feeling that their privacy rights should override FOIA rules. A phone call from a private citizen to an elected official might be logged in the incoming calls log, but the contents of that call would not become public record. On the other hand, an email to a city-provided email address is a record that can easily be made public. One respondent to our survey of city officials cited the lack of privacy for constituents who wanted to speak their mind on issues as a reason for using personal as well as official email addresses. The respondent suggested that personal email accounts are not subject to FOIA. A few others alluded to this same concern.