A majority of teens prefer in-person over virtual or hybrid learning. Hispanic and lower-income teens are particularly likely to fear they’ve fallen behind in school due to COVID-19 disruptions

Pew Research Center conducted this study to understand teens’ and parents’ experiences with schooling, virtual learning and the digital divide amid the coronavirus pandemic. For this analysis, we surveyed 1,316 pairs of U.S. teens and their parents – one parent and one teen from each household. The survey was conducted online by Ipsos from April 14 to May 4, 2022.

Ipsos invited one parent from each of a representative set of households with parents of teens in the desired age range from its KnowledgePanel, a probability-based web panel recruited primarily through national, random sampling of residential addresses, to take this survey. For some of these questions, parents were asked to think about one teen in their household (if there were multiple teens ages 13 to 17 in the household, one was randomly chosen). At the conclusion of the parent’s section, the parent was asked to have this chosen teen come to the computer and complete the survey in private.

The survey is weighted to be representative of two different populations: 1) parents with teens ages 13 to 17 and 2) teens ages 13 to 17 who live with parents. For each of these populations, the survey is weighted to be representative by age, gender, race, ethnicity, household income and other categories.

Here are the questions used for this report, along with responses, and its methodology.

More than two years after the COVID-19 outbreak forced school officials to shift classes and assignments online, teens continue to navigate the pandemic’s impact on their education and relationships, even while they experience glimpses of normalcy as they return to the classroom.

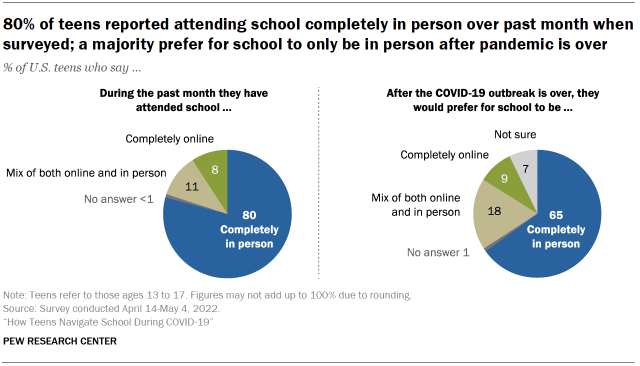

Eight-in-ten U.S. teens ages 13 to 17 say they attended school completely in person over the past month, according to a new Pew Research Center survey conducted April 14-May 4. Fewer teens say they attended school completely online (8%) or did so through a mix of both online and in-person instruction (11%) in the month prior to taking the survey.

When it comes to the type of learning environment youths prefer, teens strongly favor in-person over remote or hybrid learning. Fully 65% of teens say they would prefer school to be completely in person after the COVID-19 outbreak is over, while a much smaller share (9%) would opt for a completely online environment. Another 18% say they prefer a mix of both online and in-person instruction, while 7% are not sure of their preferred type of schooling after the pandemic.

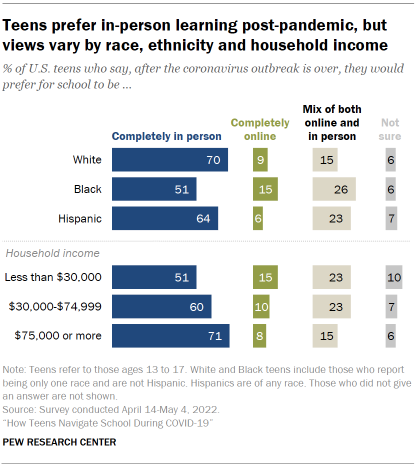

Across major demographic groups, teens favor attending school completely in person over other options. Still there are some differences that emerge by race and ethnicity and household income.

While 70% of White teens and 64% of Hispanic teens say they would prefer for school to be completely in person after the COVID-19 outbreak is over, that share drops to 51% among Black teens. At the same time, Black or Hispanic teens are more likely than White teens to prefer a mix of both online and in-person instruction post-pandemic.

In addition, 71% of teens living in higher-income households earning $75,000 or more a year report they prefer for school to be completely in person after the pandemic is over. That share drops to six-in-ten or less among those whose annual family income is less than $75,000. Preference for hybrid schooling is also more common among teens living in households earning less than $75,000 a year than among teens in households earning more.

Teens and parents express their views about virtual learning and the pandemic’s impact on educational achievement

From declining test scores to widening achievement gaps, teachers, parents and advocates have raised concerns about the negative impact the pandemic may have had on students. Beyond academic woes, experts also warn that these disruptions could have lingering effects on young people’s mental and emotional well-being.

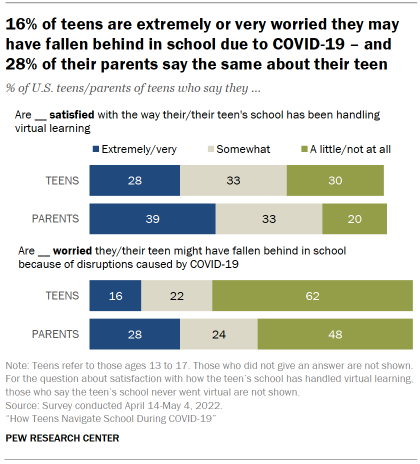

Teens hold mixed views of how their schools tackled remote schooling. Some 28% of teens say they are extremely or very satisfied with the way their school has handled virtual learning, while a similar share report being only a little or not at all satisfied with their school’s performance. Some teens fall in the middle of the spectrum, with 33% saying they are somewhat satisfied with this. (Another 9% state their school has not had virtual learning.)

In addition to having teens weigh in on these subjects, the Center also asked parents of these same teens about their child’s experience with school during the pandemic. The survey finds that parents, too, hold somewhat divided views on remote learning, though they offer a somewhat more positive assessment than their children. About four-in-ten parents of teens (39%) say they are extremely or very satisfied with the way their child’s school has handled virtual learning; 33% say they are somewhat satisfied about this, while 20% report being only a little or not at all satisfied by this.

When asked about the effect COVID-19 may have had on their schooling, a majority of teens express little to no concern about falling behind in school due to disruptions caused by the outbreak. Still, there are youth who worry the pandemic has hurt them academically: 16% of teens say they are extremely or very worried they may have fallen behind in school because of COVID-19-related disturbances.

Parents tend to express more concern than their children. Roughly three-in-ten parents report they are extremely (12%) or very (16%) worried their teen may have fallen behind in school due to the pandemic.

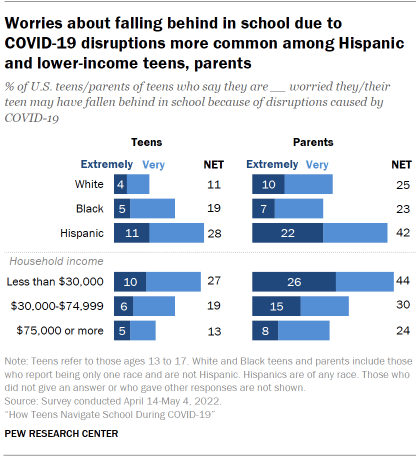

The level of concern about falling behind in school varies by race and ethnicity – for both teens and their parents.

Roughly three-in-ten Hispanic teens (28%) say they are extremely or very worried they may have fallen behind in school because of disruptions caused by the coronavirus outbreak, compared with 19% of Black teens and 11% of White teens.1 This pattern is present among parents as well. Hispanic parents (42%) are more likely than their White (25%) or Black counterparts (23%) to report being extremely or very worried their teen may have fallen behind in school during this time.

Teens and parents from lower-income households are also more likely to express concern about the pandemic’s negative impact on schooling. For example, 44% of parents living in households earning less than $30,000 a year say they are extremely or very worried their teen has fallen behind in school because of COVID-19 disruptions, but this falls to 24% among those whose annual household income is $75,000 or more. Teens from households making less than $75,000 annually are also more likely than those from households with higher incomes to express concern about falling behind in school.

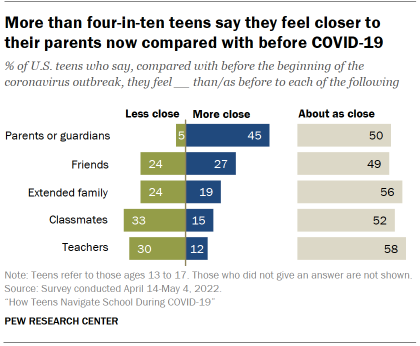

More than four-in-ten teens report feeling closer to their parents or guardians since the start of the pandemic

With recent research pointing to the negative impacts the coronavirus outbreak has had on adolescents’ social connections, teens were asked to share how their relationships may have changed since the start of the COVID-19 outbreak.

Some 45% of teens say they feel more close to their parents or guardians compared with before the beginning of the coronavirus outbreak. A smaller share says the same for their friends, extended family, classmates or teachers.

At the same time, some teens express feeling less connected to certain groups. Roughly one-third say they feel less close to classmates (33%) or teachers (30%), while 24% each feel this way about their friends or extended family. Just 5% of teens say they feel less close to their parents or guardians than they did before the pandemic.

Still, the most common responses to these questions hint at social stability. Roughly half or more teens say they are about as close to their friends, parents or guardians, classmates, extended family or teachers as they were before the beginning of the COVID-19 outbreak.

Teens’ views about how their relationships may have evolved during the pandemic share similar sentiments across many of the demographic groups explored in the study. There are, however, some modest differences by race and ethnicity. For example, Hispanic and Black teens are more likely than White teens to say they feel less close to their friends than before the pandemic.

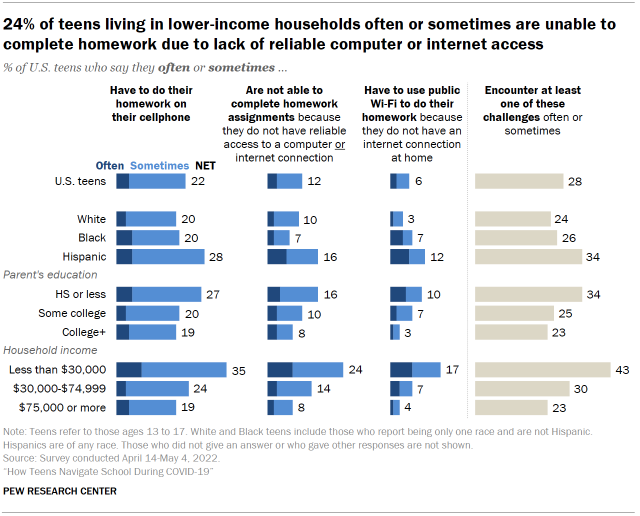

About three-in-ten teens face at least one challenge related to the ‘homework gap’

Even prior to the COVID-19 outbreak, some teens faced problems completing their homework because they lacked a computer or internet access at home – a phenomenon often referred to as the “homework gap.” And as students pivoted to virtual learning, and later shifted between online and in-person classes, access to technology and reliable internet connectivity continued to be crucial to student success.

The new survey reveals some teens – especially those from less affluent households – face digital challenges to completing their schoolwork. About one-in-five teens (22%) say they often or sometimes have to do their homework on a cellphone. Some 12% say they at least sometimes are not able to complete homework assignments because they do not have reliable access to a computer or internet connection, while 6% say they have to use public Wi-Fi to do their homework at least sometimes because they do not have an internet connection at home. (Respondents were not specifically asked to think about the pandemic when asked these questions.)

As in previous Center studies, parents’ socioeconomic status matters when it comes to homework gap challenges.2

Some 24% of teens who live in a household making less than $30,000 a year say they at least sometimes are not able to complete their homework because they do not have reliable access to a computer or internet connection, compared with 14% of those in a household making $30,000 to $74,999, and 8% of those in a household making $75,000 or more. Teens whose parent reports an annual income of less than $30,000 are also more likely to say they often or sometimes have to do homework on a cellphone or use public Wi-Fi for homework, compared with those living in higher-earning households.

There are similar patterns by parental education: Larger shares of teens whose parent has a high school diploma or less say they at least sometimes face each of the three challenges the survey asked about, compared with those whose parent has a bachelor’s or advanced degree.

When it comes to racial and ethnic differences, Hispanic teens are more likely than both Black and White teens to say they at least sometimes are not able to complete homework because they lack reliable computer or internet access, and they are more likely than White teens to say the same about having to do their homework on a cellphone or using public Wi-Fi for homework. Black and White teens are equally likely to report at least sometimes experiencing each of the three problems the survey covered.

All told, 28% of teens experience at least one of these three homework-related challenges often or sometimes. Some 43% of teens living in a household with an annual income of less than $30,000 report at least sometimes facing one or more of these challenges to completing homework – about twice the share of teens from households making $75,000 or more annually and 13 percentage points higher than the share of teens in a household making $30,000 to $74,999 annually who say so. And 34% of Hispanic teens have experienced the same – 10 points higher than the share of White teens who have experienced at least one of these challenges at least sometimes, but statistically equivalent to the share of Black teens who report this.

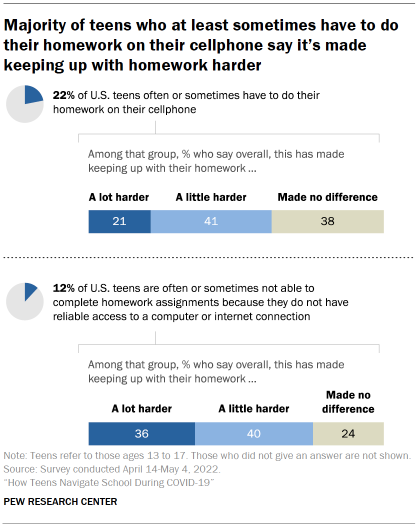

For some youth, these challenges have made it harder to keep up with their homework. Among those who have not been able to complete homework often or sometimes due to lack of reliable computer or internet access, 36% say it has made keeping up with their homework a lot harder. About one-in-five of those who at least sometimes have to do homework on their cellphone say the same.

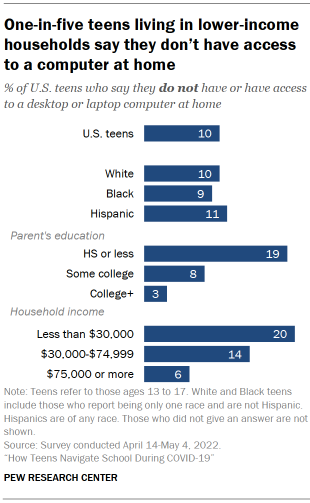

Teen computer access at home differs by parent’s level of education, household income

While most teens say they have a home computer, there are some – particularly those living in households with lower incomes or whose parent has a high school education or less – who do not have this technology at home. One-in-ten teens report not having access to a desktop or laptop computer at home.

This rises to one-in-five for those living in a household with an annual income of less than $30,000, and to a similar share (19%) for teens whose parent has a high school diploma or less formal education.