Political fissures on climate issues extend far beyond beliefs about whether climate change is occurring and whether humans are playing a role, according to a new, in-depth survey by Pew Research Center. These divisions reach across every dimension of the climate debate, down to people’s basic trust in the motivations that drive climate scientists to conduct their research.

Specifically, the survey finds wide political divides in views of the potential for devastation to the Earth’s ecosystems and what might be done to address any climate impacts. There are also major divides in the way partisans interpret the current scientific discussion over climate, with the political left and right having vastly divergent perceptions of modern scientific consensus, differing levels of trust in the information they get from professional researchers, and different views as to whether it is the quest for knowledge or the quest for professional advancement that drives climate scientists in their work.

At the same time, political differences are not the exclusive drivers of people’s views about climate issues. People’s level of concern about the issue also matters. The 36% of Americans who are more personally concerned about the issue of global climate change, whether they are Republican or Democrat, are much more likely to see climate science as settled, to believe that humans are playing a role in causing the Earth to warm, and to put great faith in climate scientists.

When it comes to party divides, the biggest gaps on climate policy and climate science are between those at the ends of the political spectrum. Across the board, from possible causes to who should be the one to sort this all out, liberal Democrats and conservative Republicans see climate-related matters through vastly different lenses. Liberal Democrats place more faith in the work of climate scientists (55% say climate research reflects the best available evidence most of the time) and their understanding of the phenomenon (68% say climate scientists understand very well whether or not climate change is occurring). Perhaps it follows, then, that liberal Democrats are much more inclined to believe a wide variety of environmental catastrophes are potentially headed our way, and that both policy and individual actions can be effective in heading some of these off. Even the Republicans who believe the Earth is warming are much less likely than Democrats to expect severe harms to the Earth’s ecosystem and to believe that any of six individual and policy actions asked about can make a big difference in addressing climate change. And, a majority of conservative Republicans believe that each of the six actions to address climate change can make no more than a small difference.

This survey extensively explores how peoples’ divergent views over climate issues tie with people’s views about climate scientists and their work. Democrats are especially likely to see scientists and their research in a positive light. Republicans are considerably more skeptical of climate scientists’ information, understanding and research findings on climate matters. A few examples:

- Seven-in-ten liberal Democrats (70%) trust climate scientists a lot to give full and accurate information about the causes of climate change, compared with just 15% of conservative Republicans.

- Some 54% of liberal Democrats say climate scientists understand the causes of climate change very well. This compares with only 11% among conservative Republicans and 19% among moderate/liberal Republicans.

- Liberal Democrats, more than any other party/ideology group, perceive widespread consensus among climate scientists about the causes of warming. Only 16% of conservative Republicans say almost all scientists agree on this, compared with 55% of liberal Democrats.

- The credibility of climate research is also closely tied with Americans’ political views. Some 55% of liberal Democrats say climate research reflects the best available evidence most of the time, 39% say some of the time. By contrast, 9% of conservative Republicans say this occurs most of the time, 54% say it occurs some of the time.

- On the flip side, conservative Republicans are more inclined to say climate research findings are influenced by scientists’ desire to advance their careers (57%) or their own political leanings (54%) most of the time. Small minorities of liberal Democrats say either influence occurs most of the time (16% and 11%, respectively).

While liberal Democrats give high marks to climate scientists’ understanding of whether climate change is occurring, even among this group, fewer give strongly positive ratings when it comes to scientists’ understanding about ways to address climate change. Minorities of all political groups say climate scientists understand how to address climate change “very well.”

Despite some skepticism about climate scientists and their motives, majorities of Americans among all party/ideology groups say climate scientists should have at least a minor role in policy decisions about climate issues. More than three-quarters of Democrats and most Republicans (69% among moderate or liberal Republicans and 48% of conservative Republicans) say climate scientists should have a major role in policy decisions related to the climate. Few in either party say climate scientists should have no role in policy decisions.

To the extent there are political differences among Americans on these issues, those variances are largely concentrated when it comes to their views about climate scientists, per se, rather than scientists, generally. Majorities of all political groups report a fair amount of confidence in scientists, overall, to act in the public interest. And to the extent that Republicans are personally concerned about climate issues, they tend to hold more positive views about climate research.

Liberal Democrats are especially inclined to believe harms from climate change are likely and that both policy and individual actions can be effective in addressing climate change. Among the political divides over which actions could make a difference in addressing climate change:

- Power plant emission restrictions − 76% of liberal Democrats say this can make a big difference, while 29% of conservative Republicans say the same, a difference of 47-percentage points.

- An international agreement to limit carbon emissions − 71% of liberal Democrats and 27% of conservative Republicans say this can make a big difference, a gap of 44-percentage points.

- Tougher fuel efficiency standards for cars and trucks − 67% of liberal Democrats and 27% of conservative Republicans say this can make a big difference, a 40-percentage-point divide.

- Corporate tax incentives to encourage businesses to reduce the “carbon footprint” from their activities − 67% of liberal Democrats say this can make a big difference, while 23% of conservative Republicans agree for a difference of 44 percentage points.

- More people driving hybrid and electric vehicles − 56% of liberal Democrats say this can make a big difference, while 23% of conservative Republicans do, a difference of 33-percentage points.

- People’s individual efforts to reduce their “carbon footprints” as they go about daily life − 52% of liberal Democrats say this can make a big difference compared with 21% of conservative Republicans, a difference of 31 percentage points.

Across all of these possible actions to reduce climate change, moderate/liberal Republicans and moderate/conservative Democrats fall in the middle between those on the ideological ends of either party.

The stakes in climate debates seem particularly high to liberal Democrats because they are especially likely to believe that climate change will bring harms to the environment. Among this group, about six-in-ten say climate change will very likely bring more droughts, storms that are more severe, harm to animals and to plant life, and damage to shorelines from rising sea levels. By contrast, no more than about two-in-ten conservative Republicans consider any of these potential harms to be “very likely”; about half say each is either “not too” or “not at all” likely to occur.

One thing that doesn’t strongly influence opinion on climate issues, perhaps surprisingly, is one’s level of general scientific literacy. According to the survey, the effects of having higher, medium or lower scores on a nine-item index of science knowledge tend to be modest and are only sometimes related to people’s views about climate change and climate scientists, especially in comparison with party, ideology and concern about the issue. But, the role of science knowledge in people’s beliefs about climate matters is varied and where a relationship occurs, it is complex. To the extent that science knowledge influences people’s judgments related to climate change and trust in climate scientists, it does so among Democrats, but not Republicans. For example, Democrats with high science knowledge are especially likely to believe the Earth is warming due to human activity, to see scientists as having a firm understanding of climate change, and to trust climate scientists’ information about the causes of climate change. But Republicans with higher science knowledge are no more or less likely to hold these beliefs. Thus, people’s political orientations also tend to influence how knowledge about science affects their judgments and beliefs about climate matters and their trust in climate scientists.

These are some of the principle findings from a new Pew Research Center survey. Most of the findings in this report are based on a nationally representative survey of 1,534 U.S. adults conducted May 10-June 6, 2016. The margin of sampling error for the full sample is plus or minus 4 percentage points.

Other key findings:

The climate-engaged public

Some 36% of Americans are deeply concerned about climate issues, saying they personally care a great deal about the issue of global climate change. This group is composed primarily of Democrats (72%), but roughly a quarter (24%) is Republican. Some 55% are women, making this group slightly more female than the population as a whole. But, they come from a range of age and education groups and from all regions of the country.

Some 36% of Americans are deeply concerned about climate issues, saying they personally care a great deal about the issue of global climate change. This group is composed primarily of Democrats (72%), but roughly a quarter (24%) is Republican. Some 55% are women, making this group slightly more female than the population as a whole. But, they come from a range of age and education groups and from all regions of the country.

There are wide differences in beliefs about climate issues and climate scientists between this more concerned public and other Americans, among both Democrats and Republicans alike. Indeed, people’s expressions of care are strongly correlated with their views, separate and apart from their partisan and ideological affiliations.

Most, but not all, among those with more personal concern about climate issues say the Earth’s warming is due to human activity. They are largely pessimistic about climate change, saying it will bring a range of harms to the Earth’s ecosystems. At the same time, this more concerned public is quite optimistic about efforts to address climate change. Majorities among this group say that each of six different personal and policy actions asked about can be effective in addressing climate change.

Most, but not all, among those with more personal concern about climate issues say the Earth’s warming is due to human activity. They are largely pessimistic about climate change, saying it will bring a range of harms to the Earth’s ecosystems. At the same time, this more concerned public is quite optimistic about efforts to address climate change. Majorities among this group say that each of six different personal and policy actions asked about can be effective in addressing climate change.

Further, those with deep concerns about climate issues are much more inclined to hold climate scientists and their work in positive regard. This group is more likely than others to see scientists as understanding climate issues. Two-thirds (67%) of this more climate-engaged public trusts climate scientists a lot to provide full and accurate information about the causes of climate change; this compares with 33% of those who care some and 9% of those with little concern about the issue of climate change. About half of those with deep personal concerns about this issue (51%) say climate researchers’ findings are influenced by the best available evidence “most of the time.” By the same token, those deeply concerned about climate issues are less inclined to think climate research is often influenced by considerations other than the evidence, such as scientists’ career interests or political leanings.

People’s views about climate scientists, as well as their beliefs about the likely effects of climate change and effective ways to address it, are explained especially by their political orientation and their personal concerns with the issue of climate change. There are no consistent differences or only modest differences in people’s views about these issues by other factors including gender, age, education and people’s general knowledge of science topics.

Media coverage on climate

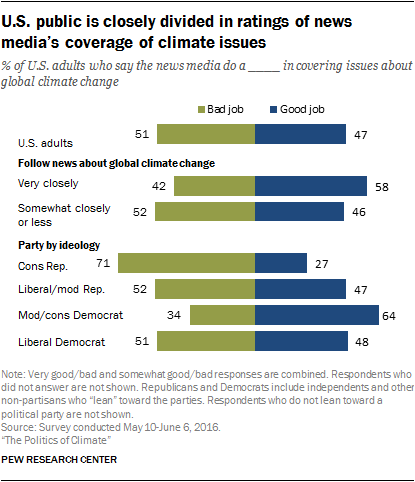

Americans are closely divided in their view of the news media’s coverage of climate change. Some 47% of U.S. adults say the media does a good job covering global climate change, while 51% say they do a bad job. A 58% majority of people following climate news very closely say the media do a good job, however. Conservative Republicans stand out as more negative in their overall views about climate change news coverage.

Americans are closely divided in their view of the news media’s coverage of climate change. Some 47% of U.S. adults say the media does a good job covering global climate change, while 51% say they do a bad job. A 58% majority of people following climate news very closely say the media do a good job, however. Conservative Republicans stand out as more negative in their overall views about climate change news coverage.

Public ratings of the media may be linked to views about the mix of news coverage. In all, 35% of Americans say the media exaggerates the threat from climate change, a roughly similar share (42%) says the media does not take the threat seriously enough; two-in-ten (20%) say the media are about right in their reporting. People’s views on this are strongly linked with political divides; 72% of conservative Republicans say the media exaggerates the threat of climate change, while 64% of liberal Democrats say the media does not take the threat of climate change seriously enough.

Public ratings of the media may be linked to views about the mix of news coverage. In all, 35% of Americans say the media exaggerates the threat from climate change, a roughly similar share (42%) says the media does not take the threat seriously enough; two-in-ten (20%) say the media are about right in their reporting. People’s views on this are strongly linked with political divides; 72% of conservative Republicans say the media exaggerates the threat of climate change, while 64% of liberal Democrats say the media does not take the threat of climate change seriously enough.

Confidence in scientists and other groups to act in the public interest

Though the survey finds that climate scientists are viewed with skepticism by relatively large shares of Americans, scientists overall – and in particular, medical scientists – are viewed as relatively trustworthy by the general public. Asked about a wide range of leaders and institutions, the military, medical scientists, and scientists in general received the most votes of confidence when it comes to acting in the best interests of the public.

Though the survey finds that climate scientists are viewed with skepticism by relatively large shares of Americans, scientists overall – and in particular, medical scientists – are viewed as relatively trustworthy by the general public. Asked about a wide range of leaders and institutions, the military, medical scientists, and scientists in general received the most votes of confidence when it comes to acting in the best interests of the public.

On the flip side, majorities of the public have little confidence in the news media, business leaders and elected officials. Public confidence in K-12 school leaders and religious leaders to act in the public’s best interest falls in the middle.

Fully 79% of Americans express a great deal (33%) or a fair amount (46%) of confidence in the military to act in the best interests of the public. The relatively high regard for the military compared with other institutions is consistent with a 2013 Pew Research Center survey, which found 78% of the public saying the military contributes “a lot” to “society’s well-being.”

Most Americans also have at least a fair amount of confidence in medical scientists and scientists to act in the best interest of the public. Some 84% of U.S. adults express confidence in medical scientists; 24% say they have a great deal of confidence and six-in-ten (60%) have a fair amount of confidence in medical scientists to act in the public’s best interests. Three-quarters of Americans (76%) have either a great deal (21%) or a fair amount of confidence (55%) in scientists, generally, to act in the public interest. Confidence in either group is about the same or only modestly different across party and ideological groups.

Confidence in the news media, business leaders and elected officials is considerably lower; public views about school and religious leaders fall in the middle.

People in both political parties express deep distrust of elected officials, in keeping with previous Pew Research Center studies showing near record low trust in government. Just 3% of Americans say they have a “great deal” of trust in elected officials to act in the best interests of the public; lower than any of the seven groups rated. Some 72% of Americans report not too much or no confidence in elected officials to act in the public interest.

Strong bipartisan support for expanding solar, wind energy production

One spot of unity in an otherwise divided environmental policy landscape is that the vast majority of Americans support the concept of expanding both solar and wind power. The public is more closely divided when it comes to expanding fossil fuel energies such as coal mining, offshore oil and gas drilling, and hydraulic fracturing for oil and natural gas. While there are substantial party and ideological divides over increasing fossil fuel and nuclear energy sources, strong majorities of all political groups support more solar and wind production.

One spot of unity in an otherwise divided environmental policy landscape is that the vast majority of Americans support the concept of expanding both solar and wind power. The public is more closely divided when it comes to expanding fossil fuel energies such as coal mining, offshore oil and gas drilling, and hydraulic fracturing for oil and natural gas. While there are substantial party and ideological divides over increasing fossil fuel and nuclear energy sources, strong majorities of all political groups support more solar and wind production.

These patterns are broadly consistent with past Center findings that climate change and fossil fuel energy issues are strongly linked with party and ideology, but political divisions have a much more modest or no relationship with public attitudes on a host of other science-related topics.

Boom for home solar ahead?

Some 41% of Americans say they have given serious consideration to installing solar panels at home (including 4% who report they have already done so). Their reasons include both cost savings and help for the environment. A similar share of homeowners (44%) have either installed solar panels (4%) or given serious thought to doing so (40%). Western residents and younger adults (ages 18 to 49) are especially likely to say they have considered, or already installed, solar panels at home. Two-thirds of homeowners in the West have considered or installed solar panels, compared with 35% of homeowners in the South, 40% in the Midwest and 38% in the Northeast.

One-in-five Americans aim for everyday environmentalism; their political and climate change beliefs mirror the U.S. population

While most Americans espouse some concern for the environment, a much smaller share says they always try to live in ways that help the environment. Three-quarters of Americans (75%) say they are “particularly concerned about helping the environment” as they go about daily living. But just two-in-ten (20%) describe themselves as someone who makes an effort to live in ways that protect the environment “all the time.” A majority (63%) say they sometimes do and just 17% do not do at all or not too often.

While most Americans espouse some concern for the environment, a much smaller share says they always try to live in ways that help the environment. Three-quarters of Americans (75%) say they are “particularly concerned about helping the environment” as they go about daily living. But just two-in-ten (20%) describe themselves as someone who makes an effort to live in ways that protect the environment “all the time.” A majority (63%) say they sometimes do and just 17% do not do at all or not too often.

Though more among this group of “everyday environmentalists” have a deep concern about climate issues, their beliefs about the causes of climate change closely match those of the public as a whole. Further, this group of environmentally conscious Americans is comprised of both Republicans (41%) and Democrats (53%) in close proportion to that found in the population as a whole.

How different are the actual behaviors of Americans who live out their concerns for the environment all the time from the rest of the public? When it comes to the list of potential activities covered in the Pew Research Center questionnaire, the answer is “not very.” Yes, those who describe themselves as always trying to protect the environment are a bit more likely do things such as bring their own reusable shopping bags to the grocery store in order to help the environment, but most do so only sometimes, at best. They are more likely to buy a cleaning product because its ingredients would be better for the environment, but again, most do so no more than sometimes. They are a bit more likely to have worked at a park cleanup day (23% vs. 11% of other adults) but no more likely to have cared for plantings in a public space. And they are no more likely than other Americans to reduce and reuse at home by composting, having a rain barrel or growing their own vegetables. Nor are environmentally conscious Americans more likely than other people to have spent hobby and leisure time hiking, camping, hunting or fishing in the past year.

There is one way in which environmentally conscious Americans stand out attitudinally, however. They are much more likely to be bothered when other people waste energy by leaving lights on or not recycling properly.

There is one way in which environmentally conscious Americans stand out attitudinally, however. They are much more likely to be bothered when other people waste energy by leaving lights on or not recycling properly.

A majority of Americans who are focused on living in ways that protect the environment say it bothers them “a lot” when they see other people leave lights and electronic devices on (62%), or throw away things that could be recycled (61%). And, sizeable minorities of environmentally conscious Americans are bothered a lot by people incorrectly putting trash in recycling bins (42%) or people driving places that are close enough to walk (34%). The least irksome behavior is drinking from a disposable water bottle; 23% of environmentally conscious Americans say this bothers them a lot, compared with 12% among those who are less focused on everyday environmentalism.

Two u2018Varietalsu2019 of Green-Oriented Americans

Two u2018Varietalsu2019 of Green-Oriented Americans