Today, 68% of Americans own a smartphone of some kind and an increasing number of digital interactions occur within the context of mobile apps. Apps (short for “applications”) are programs that users can download to their smartphone or tablet computer. They can serve a nearly unlimited range of functions — from simple tools like a calculator to advanced digital assistants. They allow users to tailor their powerful pocket computer into a device with hundreds of potential uses that meet their owners’ specific needs.

In order to function, apps may require access to both the capabilities of the devices they reside on as well as the user information contained on those devices. As users go about their lives, their mobile devices produce a vast trove of personal information and data, ranging from the user’s location to a history of his or her phone calls or text message interactions. This puts apps at the center of debates about privacy in the digital age.

All of this information can be crucial to the functioning of mobile apps. But actually accessing a device’s data or capabilities requires app developers to request it from end users in one way or another – often by asking users to click through an “I accept” box. Permissions are the mechanism by which app developers disclose how their apps will interact with users’ devices and personal information on devices running Google’s Android operating system. Once that permission is granted, the apps can amass insights from the data collected by the apps on things such as the physical activities and movements of users, their browsing and media-use habits, their social media use and their personal networks, the photos and videos they shoot and share, and their core communications. A newly released Pew Research Center survey from February 2015 finds that users place significant emphasis on how much information their apps collect from them: 90% of app users indicate that having clear information about how apps will access or use their personal data is “very” or “somewhat” important to them when deciding to download an app. Fully 60% of apps users have chosen to not download an app after discovering how much personal information the app required.

Clearly users are concerned about the information their apps require, but less is known about what is happening on the other side of the transaction — the permissions and capabilities that apps are most likely to ask for.

There is clear interest in understanding how information about mobile apps is conveyed to users. To gain more insight into the nature of the app universe as a whole and the permissions that apps require to run, Pew Research Center collected information about over 1 million apps in the Google Play Store.

We collected material about apps available in the Google Play Store between June and September 2014. The Google Play Store makes apps available for download to roughly half the smartphones (45%) owned by Americans. At the time of the data collection, the Google Play Store offered 1,041,336 apps. It is important to note that this study only looks at apps in the Google Play Store and does not cover apps available to consumers across all platforms. Pew Research Center chose to study the Google Play Store not because it is representative of the entire universe of apps across all device types, but because of the combination of both the popularity of the store and the relatively public access to the data.

In addition, Google announced a new version of Android (6.0 or “Marshmallow”) that does change the structure of permissions for Android apps, discussed in detail below. This version of Android, however, will not be available to most users at the time this report is released.1 This report provides a comprehensive look at Android apps in mid-2014 and how permissions are still displayed for most Android users:

- In the overall apps universe, there were 235 distinct types of permissions being sought across 41 different categories of apps, ranging from social networking and news apps to gaming. A table listing all the permissions, their functions and their implications can be found here.

- The average (mean) app in this dataset required five permissions before a user could install it.

- The categories of Communications and Business apps required the largest number of permissions in order to function.

- The most popular permission sought during this period allowed apps to access the internet connectivity of the smartphone.

- Of the 235 total permissions most (165) were related to allowing apps to access hardware functions of the device such as controlling the vibration function, while 70 allowed apps to access some kind of personal information.

In addition to this analysis of the Google Play Store app universe, a separate Pew Research Center survey conducted Jan. 27 to Feb. 16, 2015 found that:

- 77% of smartphone owners reported downloading apps other than the ones that came pre-installed on their phone.

- 60% of these app downloaders had chosen not to install an app when they discovered how much personal information it required in order to use it, while 43% had uninstalled an app after downloading it for the same reason.

- 90% of app downloaders said how their personal data will be used is “very” or “somewhat” important to them when they decide whether to download an app; by comparison, 57% said it is equally important to know how many times an app has been downloaded.

The findings in this study pertain specifically to apps running on the Android operating system. Pew Research Center examined the Android platform because information about these apps is available on the web via the Google Play Store website. Apps running on Apple’s iOS platform are available only through the iTunes store and not via a standard website. Given the challenges of collecting data about these iPhone and iPad apps, they are not included in this analysis.

Elaborating on key findings in the apps permission environment

The Pew Research data collection in mid-2014 compiled information on the “permissions” that Android apps required users to agree to as a condition of use. These might include simple hardware permissions — for example, allowing an app to adjust the volume of a users’ phone. Other permissions seek more detailed and potentially sensitive personal information — for example, a user’s contact lists or address book. At times, this can be crucial to the basic function of an app. At other times, such access can be a helpful convenience that allows the app to function more broadly, but it is not critical to the core mechanism of how the app functions. These permissions have wide implications for the kind of personal data Android phone users are sharing with the app’s creator.

Some of the key additional findings in our analysis of the permissions in the Android marketplace include:

The most common permissions relate to allowing the app to access the smartphone’s internet connectivity. The two most common permissions sought by Google Play apps help the app access the internet. These include the “full network access” permission (used by 83% of apps) as well as the “view network connections” permission (used by 69% of apps). The third- and fourth-most common permissions allow apps to access memory on the phone, a feature apps would need in order to save content to the device.

By category, communication and business apps require the largest number of permissions. Google breaks apps into 41 different categories, and app developers then choose which category they want their app to appear in. For this analysis, “games” was expanded into its 16 subcategories such as “arcade.”2 Among these categories, apps in the “communication” and “business” classifications require the most permissions in order to function. Communication apps require an average of nine permissions, while business apps require an average of eight. A table running through all the categories and examples of apps in each category can be found here.

The largest number of app permissions relate to hardware, rather than user information. To better understand what information apps could potentially access, Pew Research Center placed permissions into broad categories: 1) permissions that allow an app to access a hardware function of the device or 2) permissions that could potentially give the app access to any user information. Using this distinction, 70 permissions could allow an app to access user information, while 165 allow an app to control some hardware function of the device, such as allowing the app to control the vibration function of the device or control the camera flash.

The apps universe is a “long tail” system. As of fall 2014, the overwhelming majority of Android apps have been installed by only a small number of users. Around half (47%) of all apps have been installed fewer than 500 times, and more than 90% have been installed fewer than 50,000 times. On the other end of the spectrum, a relatively small number of apps have been installed by vast numbers of users — a total of four apps have been installed over 1 billion times.3 See Chapter 2 for more information on individual apps.

Why apps seek permissions

In spite of users’ concerns about the privacy implications of apps permissions, it is a simple fact that permissions are required for even the most basic apps to function. Consider, for instance, a “flashlight” app that turns on the camera flash permanently (as opposed to “flashing” like it would when taking a picture), so that it can be used as a flashlight. Even an app this basic would require the “control flashlight” permission in order to function as advertised.

Complicating the matter even further for users, app developers cannot edit the description of each permission and therefore cannot include information about why each permission is needed. This information can be included in the description of the app itself, but not with each individual permission as the user sees them. Users would have to first know what the app is supposed to do, and then evaluate the permissions that app is requesting to decide whether they are appropriate or not.

Moreover, the pure number of permissions an app requests also does not necessarily reflect how much user information it is able to access. An app with a single permission could potentially access a wealth of user information, while an app with multiple permissions might be able to interact with the phone’s hardware components but remain walled off from any personal data about the user.

Ultimately —despite user concerns about the information being requested by the apps they use — the amount of personal information users are putting at risk depends almost entirely on the individual app, the permissions it requests and the context in which those permissions are being used.

How to find permissions

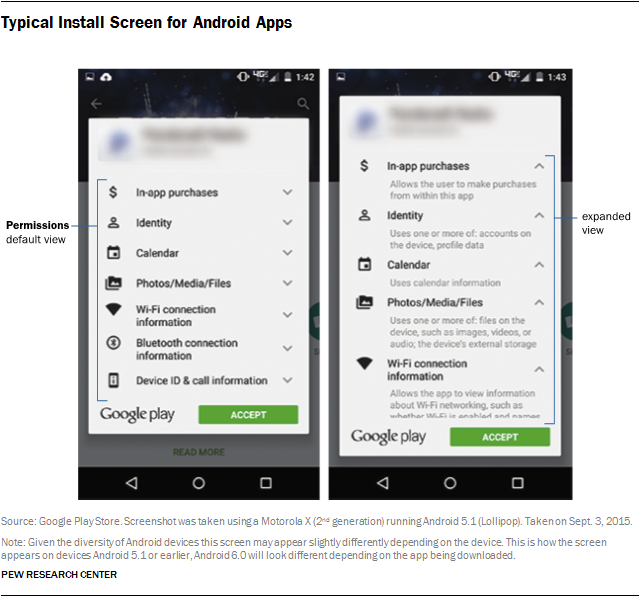

There are several places users can find the permissions an app is requesting. The most visible place is when a user chooses to download an app on their device (the other is on the web at the Google Play Store site). On an Android smartphone (or tablet) when a user chooses to download an app, they tap the “install” icon and will see a screen that looks like this:

Once apps are installed on the phone, users can typically check to see which permissions they have granted by going to the app in the Google Play Store. Permissions are always available for the user to see on each app’s Google Play page (on the web or from a mobile device). They are also updated as the app is updated.

At the moment of download, the permissions regime is “all or nothing.” In order to get an app installed on your device the first time you have to agree to all of the permissions (this regime has changed with the newest version of Android, discussed in detail below). It is also important to note that not all permissions discussed in detail in this report can be found on this screen. Android groups permissions into broader categories.

For example, the category “SMS” includes six separate permissions not all of which may be displayed on the screen above. Users can, however, see all of the permissions each app asks for in detail by going to the “settings” menu on their device and selecting “application manager” or “apps” depending on the device. The user can then select an app. Each app has a full list of the permissions it asks for here, which will contain the permissions as they are presented in this report (this is also possible through the web version of the Google Play Store).

It is important to note that this was how permissions worked until Fall 2015 when Google announced the release of Android 6.0 or “Marshmallow.” While this operating system will not be available to most users for some time, it does overhaul the way permissions are displayed.4 The main change is that on devices running Android 6.0, users will be able to toggle individual permissions on and off on an app-by-app basis. In addition, permissions will be displayed not at the moment of download, but when an app requires the particular permission. For example, an app that requires the user’s location information would prompt the user to agree to the location permissions at the moment the app needs access, users would then be able to turn this permission off later.

This change puts the Android permission structure much closer to the way the same type of information is conveyed on Apple devices. While this is a major change in how permissions are displayed, the set of permissions themselves remains the same. The data studied here reflects the individual permissions users will still have to agree to, but they will be presented to the user using this new method.

How Android App Data Was Collected

Findings about Google apps permissions in this report are based on an analysis of data about 1,041,336 apps collected from the Google Play Store between June 2014 and September 2014. The data collection or scraping (“scraping” in this case refers to the process of copying the contents of a web page) began with a custom extension for the Google Chrome web browser created by Pew Research Center developers.

The extension opens the Google Play Store website and goes to the webpage for an app as designated by a unique app ID each app in the store receives. It then copies the content of that app’s page, stores that information in a SQL database, and moves on to the next app in a continual process until no more app ID’s are available. The extension engaged in data collection from June 18 to September 8, 2014.

There are now over 1.7 million apps as of October 2015.5 Because this data is from 2014, apps introduced to the Google Play store after September 2014 are not included in this study and information about the apps included here may have changed during the time since this data was collected. The scraping process included all apps available through the Google Play Store website (except apps where there were errors in the scraping process). It did not differentiate between U.S. and non-U.S. apps and does include apps where some of the associated information is not in English.

Interactive

Interactive