Friendships also have a less pleasant side – one that includes conflict, disagreements and in some cases, the end of the relationship. Digital media plays a role in these less happy elements of teens’ friendships, both as a source of and platform for drama and conflict, and as a conduit through which the connection can be severed and walls erected when a friendship ends.

A Majority of Social Media-Using Teens Experience People Stirring Up Drama on Social Media

A Majority of Social Media-Using Teens Experience People Stirring Up Drama on Social Media

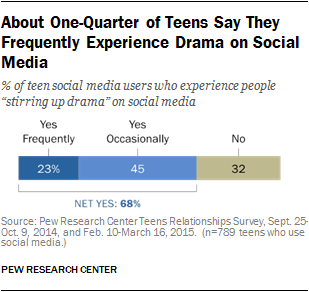

Previous research by Pew Research and others has noted that many teens use the term “drama” to describe conflict between peers, often in lieu of the term bullying. In this most recent study, 68% of teens who use social media have witnessed people stirring up drama on these platforms.

Girls are more likely than boys to say they witness the creation of drama on social media, with 72% of social media-using girls and 64% of boys encountering drama on the platforms. In a similar vein, older teens are also more likely to witness others stirring up drama on social media, with 72% of social media-using 15- to 17-year-olds seeing such behavior, compared with 62% of 13- and 14-year-olds. The oldest girls are the most likely of all groups to witness drama on social media, with 78% of them reporting such an experience.

Teens from higher-income households and whites are more likely to see people stirring up drama on social media

Teens from higher-income households are more likely to report people stirring up drama on social media sites than teens from lower-income households. Among social media-using teens whose families earn less than $30,000 in income annually, 59% say they experience people creating drama on social media, while 70% of social media-using youth from wealthier families say the same. Among both groups, teens are more likely to say they witness drama occasionally rather than frequently.

Nearly three-quarters (73%) of white teens who use social media see people foment drama on the platforms, compared with 58% of Hispanic youth. Fully 68% of black teens report seeing drama instigated on social media, a difference that is not statistically significantly from white or Hispanic teens.

Among social media users, those who use Snapchat, Twitter and Instagram are more likely than those who do not use these platforms to report seeing others create drama on social media, and Twitter and Snapchat users are among the most likely to say they see it “frequently.” Roughly eight-in-ten Snapchat users (79%) say they see this behavior on social media, with a full 28% saying they see it frequently. Among those who do not use Snapchat, 58% say they see drama created on social media and 18% see it happen frequently. Three-quarters of Twitter users see drama created through tweets and profiles and 29% say it happens frequently, compared with 64% of those who do not use Twitter (but use other social media platforms), including 19% who say it happens frequently. Among Instagram users, 73% say they see drama on social media, while 60% of those who don’t use Instagram as one of their social media platforms say the same.

Teens in our focus groups described how drama often flows back and forth from in-person to online conflict and back again. One middle school girl said, “Like it happened in school, and then they pull [Facebook] statuses and then people come running.” Another high school girl described her own experiences, “Yeah. Sometimes they just stay online with whoever I’m fighting with, and then sometimes they will blow out of proportion at school.”

One thoughtful teen explains the way the disinhibiting effects and group relationships on social media can escalate conflict. “Things blow up a lot more on social media because a lot of things people say, they wouldn’t say to, like, your face in person. Things they kind of hide behind their screen or their phone. So it blows up a lot more on social media. And then, so once it blows up, people like start feeding in or they start feeding into somebody else. It’s like if you’re at school and like that person goes to school, it just becomes so big ‘cause they like come to confront you all the sudden ‘cause they have all these people over here, and it just turns worse.”

One focus group participant also explained the way that digging through people’s online profiles and resurfacing social media postings can be used to reignite conflict. “Sometimes it’s just old drama that just comes back up. And some people might scroll down there. Like look at their past and be like, six months ago … oh yeah. Don’t you remember that day when you had this such and such?” said one high school girl. “And then the other person that was involved would be like, oh yeah, so you had so much to say. …So now it’s a fight because [of] something that happened six months ago.”

26% of Teens Have Fought With a Friend Because of Something That Happened Online

When it comes to fights moving from online to offline, most teens say digital technology has not been a main cause of disagreement among friends.

About one-in-four teens (26%) have fought with a friend because of something that first happened online or because of a text message. Still, a majority of teens (73%) have not been involved in a fight with a friend because of something that happened online.

Girls are more inclined than boys to report this type of experience: 32% of girls have been involved in a disagreement that first began online or because of a text message, compared with only 20% of boys.

Besides gender, there are also racial and ethnic differences. White teens are more likely than blacks to say they have had a fight with a friend that started in the digital realm: 29% of white teens have experienced this, compared with 15% of African-Americans. For Hispanic teens, that share is 25%, which is not a statistically significant difference from either black or white teens.

Besides gender, there are also racial and ethnic differences. White teens are more likely than blacks to say they have had a fight with a friend that started in the digital realm: 29% of white teens have experienced this, compared with 15% of African-Americans. For Hispanic teens, that share is 25%, which is not a statistically significant difference from either black or white teens.

There are no significant differences between younger and older teens.

And while there are no significant differences based on household income, there are some variances based on the level of educational attainment of a teen’s parent. Among teens whose parents have a bachelor’s or advanced degree, 30% said yes when asked if they have had a disagreement with a friend about something that happened online or via text. That share is only 18% for teens whose parents have less than a high school education.

31% of social media users have fought with a friend over something that occurred online

Besides demographics, how teens use and interact with technology is correlated with whether they have had negative experiences facilitated by the web or a text message.

Social media use is a big predictor of whether a teen has been involved in a fight over something that occurred in a digital space. Some 31% of social media-using teens say they have quarreled with a friend because of something that happened online or by text; for teens who do not use social media, that share falls to 11%.

Teens who have a smartphone are more likely than those with basic phone or no phone at all to say they have had a disagreement with a friend about something that started online. Moreover, teens who access the web via a mobile device are more than twice as likely to say they have been involved in a fight with a friend that started online than teens who are not mobile internet users (28% vs. 12%).

Teens in our focus group described some of the factors that contribute to online conflict. As one high school girl recounted, “Yeah … I had that happen before. It was a little misunderstanding on the way I typed something on Facebook. I’m like a really sarcastic person and … I don’t know. It was just the way I worded something … they took it seriously. We got into a really big fight over that. Afterwards, more people were involved. It was just like really petty and stupid. It was just ridiculous.”

Teens in our focus group described some of the factors that contribute to online conflict. As one high school girl recounted, “Yeah … I had that happen before. It was a little misunderstanding on the way I typed something on Facebook. I’m like a really sarcastic person and … I don’t know. It was just the way I worded something … they took it seriously. We got into a really big fight over that. Afterwards, more people were involved. It was just like really petty and stupid. It was just ridiculous.”

A teen girl in one of our focus groups talked about challenges with closure and trust at the end of online fights versus in-person conflicts. “I feel like there’s more closure when you do something – when you, like, finish a fight – in person rather than online because then you know for a fact, like, what this person is saying to you is true and nobody else is a part of it. But when it’s online and you resolve something, you don’t know if it’s really resolved or if someone else was like typing for them or something like that. So it’s just really confusing sometimes.”

Many Teens Have Taken Steps to Alter Their Online Presence After a Friendship Ends

Whether precipitated by conflict, growing apart or some other factor, teen (and adult) friendships end. Along with questions about online disagreements, Pew Research also asked teens about what happens in digital spaces once a friendship has ended. Fully 60% of all teens have taken an action like unfriending, blocking or deleting photos of a former friend; girls are especially likely to have done at least one of these things.

58% of teens have unfriended and unfollowed an ex-friend

58% of teens have unfriended and unfollowed an ex-friend

When a friendship ends, teens can sever ties with their former buddy by disconnecting from them on social media, either by unfriending or unfollowing, depending on the social media platform. Fully 58% of teens who are on social media or have a cellphone have unfriended or unfollowed someone that they used be friends with. As with fights that start online, girls are more likely than boys to report doing this (63% vs. 53%). Older teens are more likely than their younger counterparts to unfriend or unfollow a former friend online. Some 61% of 15- to 17-year-old teens have unfriended or unfollowed someone they used to be friends with, compared with 52% of younger teens ages 13 to 14. There are few differences among racial and ethnic groups in reporting these actions.

Older teens and girls are more likely to have blocked a former friend

Beyond unfriending, teens have another option for removing someone from their digital network: blocking. Among teens who use social media or have a cellphone, 45% have blocked someone they were once friends with. Some 53% of girls reported that they have blocked someone after their friendship ended, while 37% of boys have done so. Blocking a former friend is less prevalent among the youngest teens. For example, while 33% of 13 year-olds have blocked someone they used to be friends with, nearly half (48%) of 17 year-olds have done so.

Four-in-ten teens prune photos at the end of a friendship

Another step that some teens take after a friendship ends is going online and removing photos of a former friend. About four-in-ten (42%) teens who use social media or cellphones have untagged or deleted photos of themselves and someone they used to be friends with. This is done much more frequently among girls, as half (49%) of girls have done this compared with only about a third (35%) of boys.

Some teens have taken multiple steps to digitally disconnect from an ex-friend

Roughly a third (32%) of teen social media or cellphone users have taken all three steps of unfriending or unfollowing, blocking and untagging or deleting photos after a friendship ends. Some 16% of this group has done two of the actions and another 16% has only done one of these items.

Teen girls (38%) are more likely than their male counterparts (26%) to have done all three of these actions after the breakup of a friendship. On the opposite end of the spectrum, boys are more likely than girls to say they have not taken any of these steps — 42% of teen boys who use social media or have a cellphone have never unfriended or unfollowed, blocked, or untagged or deleted photos of a former friend, compared with 29% of girls.