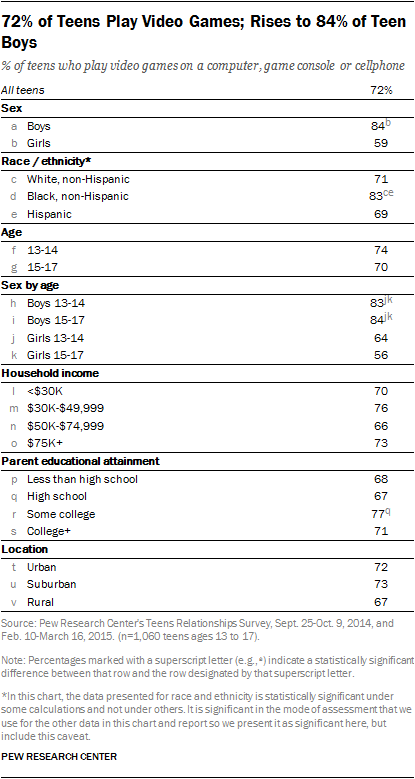

Video games8 and gameplay are pervasive in the lives of most American teens – and for boys in particular, video games serve as a major venue for the creation and maintenance of friendships. Fully 72% of all teens play video games on a computer, game console or portable device like a cellphone, and 81% of teens have or have access to a game console.

Over the past two decades, video game and internet technology have shifted, eliminating the need to be in the same room as a requirement for playing games with friends and others. Innovations in game design and platforms have increased the opportunities to interact and socialize while playing. These changes have enabled teen gamers to play games both with others in person (83%) and online (75%). Teen gamers also play games with different types of people – they play with friends they know in person (89%), friends they know only online (54%), and online with others who are not friends (52%). These capabilities have enhanced teens’ opportunities to interact and spend time with friends and others in meaningful ways while gaming.

Over the past two decades, video game and internet technology have shifted, eliminating the need to be in the same room as a requirement for playing games with friends and others. Innovations in game design and platforms have increased the opportunities to interact and socialize while playing. These changes have enabled teen gamers to play games both with others in person (83%) and online (75%). Teen gamers also play games with different types of people – they play with friends they know in person (89%), friends they know only online (54%), and online with others who are not friends (52%). These capabilities have enhanced teens’ opportunities to interact and spend time with friends and others in meaningful ways while gaming.

Boys are substantially more likely than girls to report access to a game console (91%, compared with 70% of girls) and to play games (84% of boys, compared with 59% of girls), a pattern we have seen previously in game device ownership and play.

As was noted in Chapter 1 of this report, games play an important role in the creation of teens’ friendships — and this is especially true for boys:

- More than half of teens have made new friends online, and a third of them (36%) say they met their new friend or friends while playing video games. Among boys who have made friends online, 57% have done so by playing video games online (compared with just 13% of girls who have done so).

- Nearly a quarter (23%) of teens report that they would give a new friend their gaming handle as contact information. Fully 38% of teen boys would share a gaming handle, compared with 7% of teen girls.

In the analysis that follows, we investigate more deeply the role of video games in teen friendships, with a particular focus on the way in which gaming spaces impact and contribute to friendships among boys.

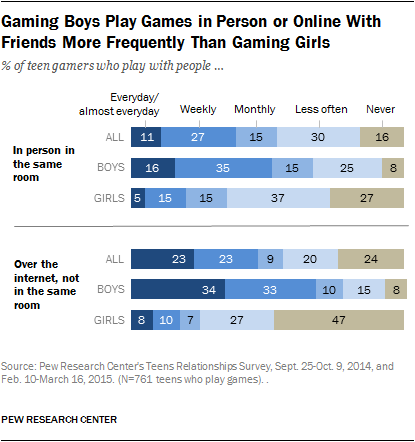

16% of boys play games with others in person on a daily or near-daily basis; 34% play games with others online almost every day

16% of boys play games with others in person on a daily or near-daily basis; 34% play games with others online almost every day

Video games are not simply entertaining media; they also serve as a potent opportunity for socializing for teens with new friends and old. Fully 83% of American teens who play games say they play video games with others in the same room, with 91% of boys and 72% of girls doing so. And boys do this more frequently. Drilling down, 16% of boys play games this way every day or almost every day, compared with just 5% of girls. A third (35%) of boys say they play together with others on a weekly basis, compared with 15% of girls who report in-person group play this often. Indeed, more than a quarter (27%) of girls who play video games say they never play with other people who are in the same room, while just 8% of boys say this.

Younger boys who game are especially likely to play together in same room as others – more likely than any groups of girls who game. Among teen gamers, 94% of 13- to 14-year-old boys do this, compared with 84% of girls the same age and 64% of girls ages 15 to 17.

91% of video-gaming boys play with others who they are connected with over a network; one-third of boys say they play this way every day or almost every day

Advances in networks, as well as console and computer capabilities, mean there are more ways to play with others than there have been in the past. Often, these modes of group play are more accessible than in-person group play.

Three-quarters of teens who play games play them with others with whom they are connected over the internet. Nine-in-ten boys (91%) who play games play with others online – identical to the percentage of boys who play games together in person. Just over half of girls who play games (52%) say they play together with others over the internet, fewer than those who report playing with others in person.

Not only are boys more likely than girls to play games with others over a network, they do so with much greater frequency. While a third (34%) of boys play video games with others over a network daily or almost every day, only 8% of girls do. Another third of boys (33%) play with others over a network weekly, while 10% of girls report playing this way. Girls who play games, on the other hand, are most likely to report that they play networked games with others less often than monthly (27%) or that they never play in such a manner (47%).

Teens mostly play networked games with friends; more than half of boys also play with online only friends and strangers

Many teens play games with pals as a part of in-person friendships. But teens also play with people they know only online. Among boys and girls who play games with others over a network, 90% of networked-gaming boys and 85% of girls are playing these games with friends they know in person (for a total of 89% of all teens). But when it comes to friends known only online or individuals who aren’t friends, but are game partners, boys who play online games are substantially more likely to say they play with or against these types of people. While 40% of girls who play with others online play with friends they know only online, 59% of boys say they play with online-only friends, and that number rises to 62% of boys ages 15 to 17.

Many teens play games with pals as a part of in-person friendships. But teens also play with people they know only online. Among boys and girls who play games with others over a network, 90% of networked-gaming boys and 85% of girls are playing these games with friends they know in person (for a total of 89% of all teens). But when it comes to friends known only online or individuals who aren’t friends, but are game partners, boys who play online games are substantially more likely to say they play with or against these types of people. While 40% of girls who play with others online play with friends they know only online, 59% of boys say they play with online-only friends, and that number rises to 62% of boys ages 15 to 17.

Teens who play games in a networked environment also play with and against other people they do not consider to be friends. Just over half of teens who play with others online say they play with people they don’t consider friends. Similar to the percentage with online-only gameplay friends, 57% of boys and 40% of girls say they play games with people they do not consider their friends. And again, the oldest boys (ages 15 to 17) are more likely (60%) than girls of any age to report playing with or against others who are not friends.

In our focus groups, the responses to questions about who teens play with ran the gamut. One high schooler told us, “I play with everyone,” while another explained, “I play with friends and then I meet new people through those friends.” A third high school boy told us, “I usually play on the internet … [with] people I don’t really know.”

Some teens noted they particularly enjoy playing with people who are not their friends. Some teens told us that they relish the competitive aspect of playing with unknown quantities. “It’s more competition like that,” said one high school boy. Another added, “It’s more fun like that, too. … Because, like, you don’t know what they’re capable of and you don’t know if they can do it. … When you’re playing with people you don’t know, it’s like you’re trying, like, to play harder and see what they’re about.”

Other teens told us they liked playing games because they could be a different person. A high school boy explained how “you use an alter ego” when playing. And still others benefit from the opportunity to take out their frustrations on people they would never interact with again. As a high school boy told us, “If you, like, have a bad game, instead of throwing your controller, you can just take it out on them.”

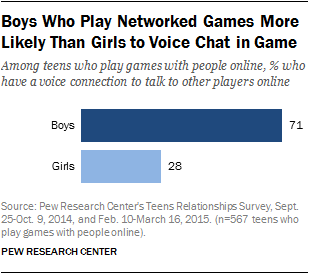

59% of teens who play online with others use a voice connection when they play

Networked online gameplay becomes a vehicle for friendship, interaction and trash talk when the players connect with each other by voice as well as through the mechanics of the game. Nearly six-in-ten teens who play games online with others use a voice connection – through the console, the game or a separate platform (e.g. Skype). Use of a voice connection is heavily skewed towards boys – 71% of boys who play networked games use a voice connection so they can talk with other players as they play, compared with 28% of girls who play games online with others. Older boys drive this finding, with 75% of boys 15 to 17 who play networked games with others using a voice connection when they play online.

Networked online gameplay becomes a vehicle for friendship, interaction and trash talk when the players connect with each other by voice as well as through the mechanics of the game. Nearly six-in-ten teens who play games online with others use a voice connection – through the console, the game or a separate platform (e.g. Skype). Use of a voice connection is heavily skewed towards boys – 71% of boys who play networked games use a voice connection so they can talk with other players as they play, compared with 28% of girls who play games online with others. Older boys drive this finding, with 75% of boys 15 to 17 who play networked games with others using a voice connection when they play online.

These voice connections enable all types of communication through the game – conversations about mundane things, strategizing in-game play and trash talking.

One middle school boy in our focus groups explained that he and a gaming friend talked about a mix of things pertaining to the game and their lives: “Like, we were talking about the game and then I’d be like, so, what do you like to do? And we would just share thoughts. Stuff.” Other teens told us that this type of interaction was “very rare.” And that usually it’s, “No hi’s. No bye’s. No hellos.”

Focus group data suggests that trash talking is pervasive in online gaming and that it can create a challenging conversational climate. As one high school boy told us, “If you’ve ever been on any form of group chat for a game, yeah. It’s harsh. … It’s funny, though. Unless you take it seriously. Cause some people take certain things personally.”

For some teens, trash talking is an integral and even enjoyable part of playing networked games. A high school boy related his experiences: “You find a lot of people from overseas playing the games. They’re really good, but they do a lot of trash talking. You’re like I’m getting trash talked in Korean, but that’s what’s happening.” One teen told of trying to use online translators to figure out what his opponents were saying only to “find out he’s sending [me] a death threat.”

Other teens told us that they only trash talk with people they know: “Oh, with my friends? Yeah. I trash talk,” said a middle school boy. “Overall, with people I don’t know, I don’t.” Teens told us this was because their friends knew they were “just kidding.”

Some teens do not use the voice connection to trash talk, but instead to plan game play. In one of our focus groups, an interviewer asked “And are you talking about other stuff, or are you mostly trash-talking about the game?” And a high school boy responded. “Not trash-talking; strategizing.”

A high school girl described how she used Skype to strategize and socialize with friends while gaming: “Skype. … I use Skype with my friends pretty often … because we play a lot of games together, so … I Skype them, and then we get into the same game together. That way we can hear each other and tell each other, like, where we are.”

And some younger teens were put off by the language and name-calling of trash talking. As one middle school boy explained, “For ‘Call of Duty,’ there’s like no filter. So you have those 20-year-old rage people that every time you make mistakes they’re like screaming and swearing at you and it’s really annoying. You have to leave.”

Another middle school boy talked about being pushed off the game by trash talking: “It was yesterday. I was playing with my friend. ‘Battlefield.’ I was trying to talk to my friend and this kid’s like, ‘Shut up. You’re annoying’ or something. And then I just like left the game and invited him [my friend]. And the guy that was trash talking joined me. I don’t know how. He started trash talking, so I just got off everything.”

Older teen boys talked about how younger teens, in this case siblings, needed to learn how to handle trash talk in games. “No, they have to do the same thing,” said a high school boy. “It’s for the game.”

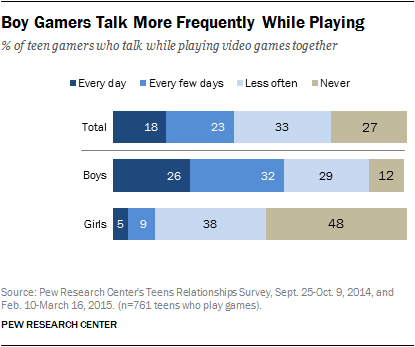

Talking with friends while playing a video game is a major way boys talk with friends

Whether on headsets or in person, teens who play networked games talk with their friends while they play. Nearly three-quarters of teens who play online video games say they’ve talked with friends while they played together. Nearly nine-in-ten online video-gaming boys (88%) say they talk with their friends while playing, while about half (52%) of online gaming girls do.

Boys talk with friends while playing games more frequently than girls as well, with 26% of teen boys who play games reporting that they talk with friends every day while they play, and another 32% of gaming boys talking with friends over games every few days. Girls, by contrast, report substantially lower frequencies, with 5% of girls who play networked games talking with friends every day while they play and 9% talking while playing every few days.

Boys talk with friends while playing games more frequently than girls as well, with 26% of teen boys who play games reporting that they talk with friends every day while they play, and another 32% of gaming boys talking with friends over games every few days. Girls, by contrast, report substantially lower frequencies, with 5% of girls who play networked games talking with friends every day while they play and 9% talking while playing every few days.

And as noted previously, when comparing talking by video gaming to other modes of communication and interaction with friends, gaming ranks substantially higher for boys as a mode of daily communication than it does for girls, for whom it ranks at the very bottom.

For the bulk of teens who play games online with others, playing makes them feel connected to friends

Playing games can have the effect of reinforcing a sense of friendship and connectedness for teens who play online with friends. Nearly eight-in-ten online-gaming teens (78%) say they feel more connected to existing friends they play games with. For teen boys, this is especially true – 84% of boys who play networked games say they feel more connected to friends when they play, compared with 62% of girls. The depth of teens’ sense of connectedness to friends when playing online with others is evenly divided for both genders, with about 38% of teens saying “yes, a lot” in response to the connectedness question and another 40% replying “yes, a little.”

Networked gameplay is less effective at connecting online-gaming teens with those who are not yet their friends. Just about half (52%) of teens say playing networked games helps them feel connected to the people they aren’t otherwise connected to. Once again, boys are more likely to report ever feeling this way than girls, with 56% saying they feel more connected to other players, and 43% of girls reporting such feelings. Further, most teens who say they feel connected to the people they play with or against say these feelings are relatively minor, with most teens saying they feel connected “a little” to the people (who are not their friends) they play games with online.

Networked gameplay is less effective at connecting online-gaming teens with those who are not yet their friends. Just about half (52%) of teens say playing networked games helps them feel connected to the people they aren’t otherwise connected to. Once again, boys are more likely to report ever feeling this way than girls, with 56% saying they feel more connected to other players, and 43% of girls reporting such feelings. Further, most teens who say they feel connected to the people they play with or against say these feelings are relatively minor, with most teens saying they feel connected “a little” to the people (who are not their friends) they play games with online.

Online gameplay also has the ability to provoke anger and frustration as well as relaxation and happiness in the teens who play. A larger percentage of teens say playing games allows them to feel more relaxed and happy than the percentage who report anger and frustration. Fully 82% of teens say they feel relaxed and happy when they play, with 86% of boys and 72% of girls reporting these experiences. Girls who play these games are less likely to say they feel relaxed and happy when they play, with 28% reporting they don’t feel that way, compared with 14% of boys.

The flip side is that playing games also can provoke feelings of anger or frustration in those who play games with others online. While fewer teens report feelings of anger or frustration than more positive emotions, when they play online with other people, 30% say they feel more angry or frustrated, with one third of boys and 20% of girls reporting these feelings.

The flip side is that playing games also can provoke feelings of anger or frustration in those who play games with others online. While fewer teens report feelings of anger or frustration than more positive emotions, when they play online with other people, 30% say they feel more angry or frustrated, with one third of boys and 20% of girls reporting these feelings.

A middle school boy in one of our focus groups describes getting angry while playing video games. “Like say I’m playing ‘Call of Duty’ with my friends and we’re on the same team. Sometimes if I mess up or he messes up, we’ll get mad at each other and then we’ll delete each other as a friend. And then, like, we’ll get all mad at each other the next day and we won’t talk to each other. Then when we get home, we’ll make up. So, I mean, it’s kind of just like getting mad at each other for dumb reasons over the internet.”

The same teen later described the difference between frustration over poor play in an in-person game (like basketball) and a video game: “It’s kind of difficult because I feel like sometimes in basketball, I wouldn’t get as mad because they tried making a shot or they tried doing something. Maybe they were off by a little bit. [With video games] we’re playing the game or we’re trying to do something to beat it and they’re just messing around and it’s like, well, you spent money on this game to beat it and your friend is messing around and you can’t accomplish what you bought the game for. And it just gets you angry about that. But in basketball, you didn’t really have to pay for something. You’re just playing with your friends.”

Teens, Video Games and Friends: Other Demographic Differences

Teens’ gaming habits vary little by family income, education or race and ethnicity. Below we highlight the most notable differences between groups in how their use of video games intersects with their friendships.

Higher-income teens are more likely to play networked game with friends they know in person

Higher-income teens are more likely than low-income ones to play networked games with friends they know in person; 94% of teens whose families earn more than $50,ooo annually play networked games with in-person friends, 78% of teens from families earning less say they play online with in-person friends. Teens from all income groups are equally likely to say they play with friends they know only online or people they play with online, but don’t consider friends.

Gaming teens from middle- and upper-income households earning more than $50,000 a year are also more likely to have a voice connection to other players – which allows them to strategize and talk to one another – when they play games online. Fully 63% of teens from households earning more than $50,000 have a voice connection, while just half (51%) of teens from households earning less do.

Gaming teens from middle- and upper-income households earning more than $50,000 a year are also more likely to have a voice connection to other players – which allows them to strategize and talk to one another – when they play games online. Fully 63% of teens from households earning more than $50,000 have a voice connection, while just half (51%) of teens from households earning less do.

Teens from the lowest-income homes are the most likely to say they feel connected to people they are not friends with when they play online games with others. Nearly two thirds (64%) of teens from families earning less than $30,000 annually say they feel connected to others who aren’t friends when they play games online, compared with just half of teens from families earning more than $30,000 per year.

Teens from families earning less than $50,000 annually are more likely to say they feel relaxed and happy when they play games online with others with nine-in-ten (90%) teen online gamers from lower-income households saying they feel that way, compared with 78% of networked teen gamers from wealthier households.

Urban and suburban teens more likely to play networked games with others

Rural teens are less likely to play with others online, but, if they do, they are more likely to play with people they know only online. Fully 78% of urban teens and 77% of suburban teens who play games do so in a networked environment with others, while 59% of rural gamers report such gameplay.

Suburban kids who play networked games are more likely than rural kids to play games online with friends they know in person; 92% of suburban kids play with friends they know in person, compared with 77% of online-gaming rural teens. Conversely, rural teens who play networked games are more likely than suburban teens to play with friends that they only know online. A full 70% of rural teens play games online with friends they know only online, while just half (51%) of suburban teens play online with online-only friends. Networked gamer teens from all types of communities are equally likely to play online games with people they don’t know and don’t consider friends.

Teens of different racial and ethnic groups sometimes have different experiences and reactions when they are gaming

There are few differences between black, Hispanic and white teens when it comes to friends and video gameplay. While black teens (83%) are more likely to play video games than white teens (71%) or Hispanic teens (69%), white teens are more likely than black teens (62% vs. 40%) to have a voice connection when they play networked games with other people – which allows players to strategize and talk while playing.

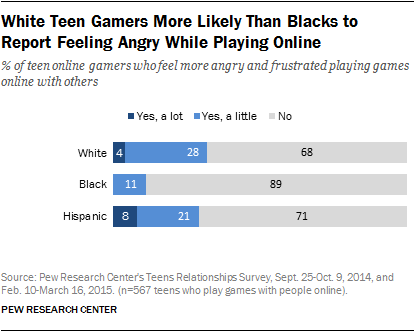

White and Hispanic teens are more likely than black teens to report feeling more angry and frustrated when they played networked games with others. Nearly a third of white teens (32%) and 29% of Hispanic teens report ever feeling more angry and frustrated (although most of these teens say this is something that happens only “a little”) when they play online with others, while just 11% of black teens report these types of emotions while playing networked games.

White and Hispanic teens are more likely than black teens to report feeling more angry and frustrated when they played networked games with others. Nearly a third of white teens (32%) and 29% of Hispanic teens report ever feeling more angry and frustrated (although most of these teens say this is something that happens only “a little”) when they play online with others, while just 11% of black teens report these types of emotions while playing networked games.