About the report

This report is part of a larger research effort by the Pew Research Center’s Internet & American Life Project that is exploring the role libraries play in people’s lives and in their communities. The research is underwritten by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.

This report contains findings from a nationally representative survey of 6,224 Americans ages 16 and older fielded July 18-September 30, 2013. It was conducted in English and Spanish on landline and cell phones. The margin of error for the full sample is plus or minus 1.4 percentage points. Unlike standard Pew Research surveys of adults 18 and older, this report also contains data on Americans ages 16-17. However, any analyses of behaviors based on education level or household income level exclude this younger age group and are based solely on adults ages 18 and older, which is also noted throughout the report.

Disclaimer from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation

This report is based on research funded in part by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. The findings and conclusions contained within are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect positions or policies of the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.

Acknowledgements

A number of experts have helped the Pew Research Center’s Internet Project in this research effort:

Andrea Berstler, Director, Wicomico Public Library, Maryland

Daphna Blatt, Office of Strategic Planning, The New York Public Library

Richard Chabran, Adjunct Professor, University of Arizona, e-learning consultant

Larra Clark, American Library Association, Office for Information Technology Policy

Mike Crandall, Professor, Information School, University of Washington

Catherine De Rosa, Vice President, OCLC

LaToya Devezin, American Library Association Spectrum Scholar & librarian, Louisiana

Amy Eshelman, Program Leader for Education, Urban Libraries Council

Christie Hill, Community Relations Director, OCLC

Sarah Houghton, Director, San Rafael Public Library, California

Mimi Ito, Research Director of Digital Media & Learning Hub, University of California Humanities Research Institute

Chris Jowaisas, Senior Program Officer, Global Libraries, Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation

Patrick Losinski, Chief Executive Officer, Columbus Library, Ohio

Jo McGill, Director, Northern Territory Library, Australia

Dwight McInvaill, Director, Georgetown County Library, South Carolina

Rebecca Miller, Editorial Director, Library Journal & School Library Journal

Bobbi Newman, Blogger, Librarian By Day

Annie Norman, State Librarian, Delaware

Carlos Manjarrez, Director, Office of Planning, Research & Evaluation, Institute of Museum & Library Services

Johana Orellana-Cabrera, American Library Association Spectrum Scholar & librarian, Texas

Gail Sheldon, Director, Oneonta Public Library, Alabama

Sharman Smith, Executive Director, Mississippi Library Commission

Global Libraries staff at the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation

About this typology

What is a typology?

Briefly put, a typology is a statistical analysis that clusters groups based on certain attributes. In this case, the typology was built around people’s use of libraries, their views about libraries and library services, and their access to libraries.

Why use a typology instead of more familiar demographics?

Pew Research has reported in extensive detail how different demographic groups use libraries, library web sites, and a broad array of library services. That work can be found in our archives and contains numerous insights about gender differences, racial and ethnic differences, age differences, differences by community type (urban, suburban, rural), and socio-economic differences.

This typology enriches that picture considerably by moving beyond familiar groups by fitting demographics into contexts that matter to the library community. It is also useful to anyone interested in sweeping technology changes in America—how people get, use, share, and think about information and a key institution that offers information at no charge. Not all Hispanics or men or rich people or high school dropouts or suburbanites act and think the same way. By creating groups based on their connection to libraries rather than their gender, race/ethnicity, or socio-economic attributes, this report allows portraiture that is especially relevant to the public library community.

This work also differs from a typical survey report by the Pew Research Center in that it focuses on analyses of groups, rather than individual respondents. Thus, we do not devote much space to elaborating the national findings on issues such as how many patrons used different library services, or how many books Americans read. Those who care about that can find the information in earlier reports such as our recent report on Americans’ reading habits. We focus instead on how their book reading fits them into different kinds of groups that explore their library use and attitudes.

About this typology

This typology is built around the current state of libraries in America: their importance to people’s lives, how they are viewed, and the role they play in their communities. Because this is based on survey data of individual Americans’ experiences and opinions, not all of the work libraries do will be visible. Yet this report contains important information about the relationship people have to public libraries at a time when reading and information habits are adapting to new technologies and economic realities, and when libraries’ strong (though often subtle) place in American culture is the subject of much discussion.

The first thing to know is that the groups in this typology are defined by their engagement with libraries, not demographic characteristics such as gender, age group, race/ethnicity, or household income. We often discuss their demographics and other characteristics as a way to describe who is in these groups and what these groups look like—but characteristics such as age or income do not determine which group someone is placed in. For instance, the “Young and Restless” group does include a higher proportion of young people than the population as a whole (who are more likely to be new to their neighborhoods—the “restless” part of the name), the group does not represent all young people, or even all young “restless” respondents. Rather, low engagement library users who do value libraries but do not know where their local library is (two of the defining traits of the Young and Restless group) are simply more likely to be young than other low engagement groups.

In addition to demographic information, we also report other information about these groups’ habits and attitudes. For instance, we asked about how active they are in attending various gatherings and institutions, from sporting events to museums and art galleries. We also asked several questions about their basic information practices and views: Do they read books, enjoy following the news, or feel comfortable using newer technologies? Would they need help filing their taxes, or learning about relevant government benefits and services? Though their responses to these questions did not inform the typology, they can help provide context for these groups’ lives in their communities beyond libraries.

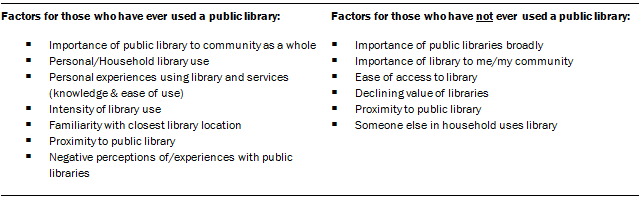

The second thing to understand about this typology is that it is not exclusively a typology of library users—it’s a typology of Americans’ attitudes, perceptions, and priorities relating to public libraries, in addition to the basic contours of their library use. The following chart shows which factors were used in creating the analysis; for more information about the exact questions that each component was based on, please see the methods section (see Creating the typology) at the end of this report.

Another thing readers may notice is that the groups outlined in this report are not always strongly delineated. In fact, the groups with the highest levels of public library engagement tend to look very similar, and may be best understood as existing along a gradient of library use and values. The lower engagement groups, by contrast, are often both smaller and more distinct.

Finally, while this typology contains many national-level insights that may be of interest to the public library community, it cannot answer individual libraries’ questions about how to allocate their resources, or who their patrons are—nor is it meant to replace the hard work libraries already do to identify needs in their communities, or librarians’ deep knowledge about the patrons they serve. Our hope is that this data might lay the foundation for a national conversation by illuminating the habits and attitudes of these groups in a way that lets individual readers understand the larger role libraries play, beyond those readers’ individual experiences.

Quiz

Quiz