58% of teens have downloaded an “app” to their cell phone or tablet computer.

As part of an ongoing collaboration with the Berkman Center for Internet & Society at Harvard University to study American teens’ technology use and privacy-related behaviors, the Pew Internet Project has undertaken a study that focuses specifically on youth use of mobile software applications or “apps,” using both a survey and focus group interviews. The focus on apps in this study follows policy maker1 and advocates’ interest in the topic, as growing numbers of teens gain access to internet-enabled smartphones and tablet computers.2

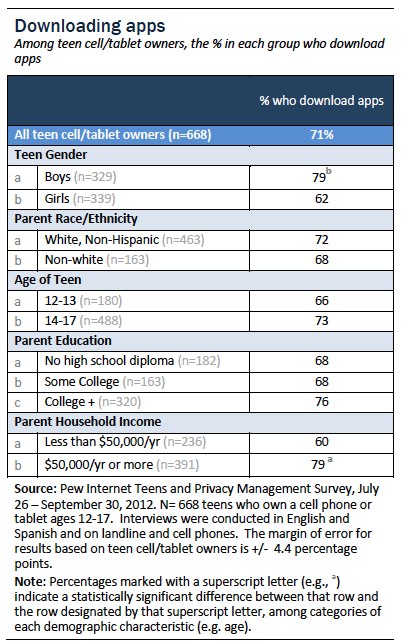

The nationally representative survey of youth and parents finds that 58% of all U.S. teens ages 12-17 have downloaded a software application or “app” to their cell phone or tablet computer. Among American teens, 78% of teens have a cell phone3 and 23% of teens have a tablet computer; 82% own at least one of these mobile devices. Within this subgroup of teens who own cell phones or tablets, 71% say they have downloaded an app to one of those devices. These figures are higher than similar measures of adult app downloading on mobile devices.4

As noted in previous reports, older teens are more likely than younger teens to own cell phones, but teens of all ages are equally likely to own tablets.5 However, among teens who own at least one of these mobile devices, app downloading does not vary significantly by age; 66% of those ages 12-13 download apps, compared with 73% of those ages 14-17.

While cell phone ownership does not vary by gender and teen girls are somewhat more likely to own tablet computers, boys are the ones who stand out as the most active app downloaders. Boys who are mobile device owners are significantly more likely than girls to say that they have downloaded an app to their cell phone or tablet computer (79% vs. 62%).

Teens living in wealthier households are more likely than those in lower income homes to download apps. Eight in ten (79%) teen mobile device owners living in households earning $50,000 or more per year download apps, compared with 60% of those living in households earning less than $50,000 per year. Teen app downloading does not vary significantly according to a parent’s education level or by their race or ethnicity.

Focus group discussions suggest that teens often choose free apps.

In focus group discussions with teens, participants said they primarily downloaded social media and game apps to their phones and tablets, though they also downloaded apps relating to music, news, and the weather. When choosing which apps to download, participants stated that they typically downloaded free ones:

Female (age 13): “Usually, I just stick to free ones. Because if I don’t like it, I can just delete it. And it doesn’t matter.”

Female (age 12): “A lot of times I don’t have money [to download an app that costs money], so it [downloading the free one] is my only option.”

Female (age 13): “You can’t be sure if it’s going to be a good app but if it’s free, you can just delete it.”

Female (age 17): “[For some apps,] there’s one or two added benefits to paying for it. But they’re not so substantial that you need to have it and need to pay $1.99.”

Female (age 17): “[I download] whichever one [app] is free.”

Female (age 17): “I don’t think I’ve ever paid for an app.”

However, participants also considered a variety of factors to determine the quality of the app. These factors included the number of downloads, the reviews, the ratings, and the appearance of the app:

Female (age 19): “I look at the pictures to see if the game is cool.”

Female (age 13): “I look at the reviews, and pictures, to see what they look like.”

Female (age 17): “I look at the reviews on Google Play. I look to see what people are saying.”

Male (age 17): “If it got a million downloads, I’m like, OK, it’s cool, people are downloading. But if it’s got like ten downloads…”

Although teens may be downloading free apps because of financial considerations, or being able to delete the app without consequence if they don’t like it, it can sometimes be related to the fact that teens may not need permission from their parents when downloading free apps:

Interviewer: “Do you have to ask your parents before you download an app?”

Female (age 12): “I have to ask if it costs money but if it is free…”

Half of teen apps users have avoided an app due to concerns about the personal information they would have to share in order to use it.

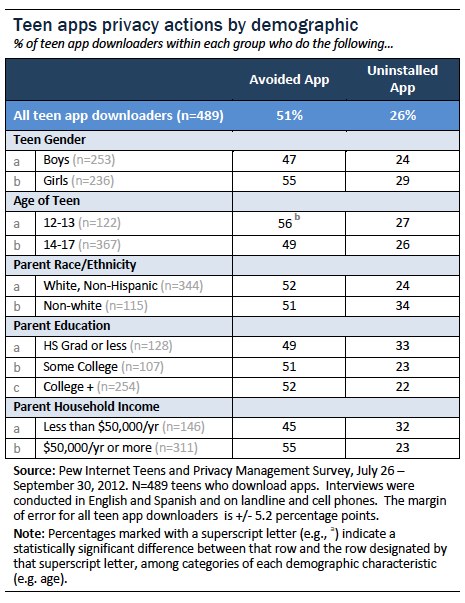

As we have found with adults, many teen apps users also avoid certain apps when they have privacy concerns.6 Half (51%) of teen apps users say that they have decided not to install a cell phone or tablet app after they found out they would have to share personal information in order to use it.7

Younger teen apps users ages 12-13 are more likely than older teen apps users 14-17 to say that they have avoided apps over concerns about personal information sharing (56% vs. 49%). Boys and girls are equally likely to avoid certain apps for these reasons. There are no clear patterns of variation according to the parent’s income, education level or race and ethnicity.

One in four teen apps users have uninstalled an app because they found out it was collecting personal information that they didn’t want to share.

A smaller segment of teen apps users (26%) say they have removed an app from their cell phone or tablet after they found out it was collecting personal information that they didn’t wish to share.8 Boys and girls and teens of all ages who are app downloaders are equally likely to say they have uninstalled apps for this reason. As is the case with avoiding apps, there are no clear patterns of variation in app deletion according to the parent’s income, education level or race and ethnicity.

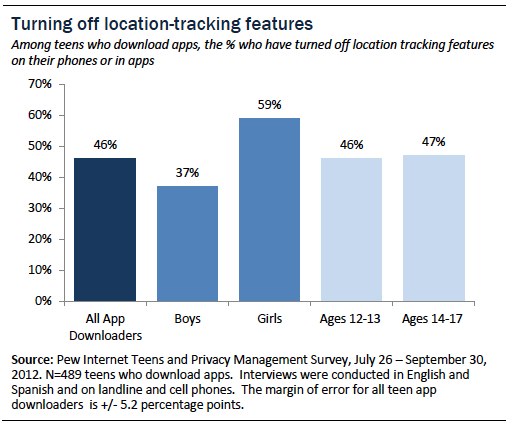

Close to half of teen apps users have turned off location tracking on their cell phone or in an app because they were worried about other people or companies accessing that information.

Location-based information is considered sensitive for many teen apps users. Some 46% of them have turned off the feature on their cell phone or in an app because they were worried about other people or companies having access to that information. However, some of the people they are concerned about may be their own parents. As early as 2009, the Pew Internet Project found that about half of parents of teen cell phone owners said they used the phone to monitor their child’s location in some way.9

Girls are far more likely than boys to say that they have turned off location tracking features on their cell phone or in an app. Among app downloaders, 59% of teen girls said they had disabled location tracking, compared with just 37% of teen boys. Teens of all ages are equally likely to turn off location tracking features on their phones and apps.

As is the case with avoiding and uninstalling apps, the likelihood that a teen apps user will disable a location tracking feature does not vary significantly according to the parent’s income, education level or race and ethnicity.

Focus group participants understood that apps can access various data on their smartphones and tablets, such as their pictures, contacts, or location. In many cases, they reported that they did not allow an app to access their location, unless they thought it was necessary.

Interviewer: “Do you ever worry about what kind of data apps are taking from your phone?”

Male (age 18): “They [the app] request [access to personal information]. I didn’t really know what it [the app] was using it [personal information] for. Like an app wanted to use location services for some reason. But I didn’t see the reason why.”

Female (age 19): “It [the app] tells you what it does on the description thing. It tells you that it can collect data if it wants to. So you’re aware of that.”

Female (age 17): “You can just reject the [app’s access to] information and still get the app.”

Female (age 13): “I always hit ‘don’t allow’ to use my location.”

Male (age 13): “Yeah, I hit don’t allow when it says that [this app would like to use your current location]…unless it’s very necessary for the app.”

Female (age 13): “Like Google Maps – if you’re trying to find your way to somewhere, [sharing your location is] necessary.”

However, some focus group participants aligned with the less concerned segments of teen apps users and did not express a high level of concern that apps might collect information about them. Although some reported deleting apps (along with the data stored on their devices) when they no longer used them, they did not report any concerns about the app continuing to have their information through app-specific accounts or other means.

Male (age 13): “I usually just hit allow on everything [when installing an app]. Because I feel like [the app] would get more features. And a lot of people allow, so it’s not like they’re going to single out my stuff. I don’t really feel worried about it.”

Female (age 16): “I think the only apps I’ve ever had that accessed my pictures were my Facebook and my Twitter. But if I have pictures, they’re probably already out there.”

Female (age 19): “I mean, the only thing on my phone is just pictures and messages. So it’s not really like, “oh, you’re [the app company] going to take my identity or anything,” so it doesn’t really matter.

Male (age 16): “I felt fine with it [apps accessing my personal information]. I always let them access my pictures and everything.”

In the survey, teens who had at some point sought outside advice about privacy management were considerably more likely than those who had not sought advice to say that they had disabled location tracking features. As the Pew Internet Project reported recently, 70% of teen internet users have sought advice from someone else at some point about how to manage their privacy online.10 Among these “online privacy advice seekers” who own mobile devices, 50% have turned off the location tracking feature on their cell phone or in an app, compared with 37% of those who have not sought outside advice on ways to manage their privacy online. Avoiding and uninstalling apps was equally prevalent among advice seekers and non-seekers alike.