Digital differences

When the Pew Internet Project first began writing about the role of the internet in American life in 2000, there were stark differences between those who were using the internet and those who were not.20 Today, differences in internet access still exist among different demographic groups, especially when it comes to access to high-speed broadband at home. Among the main findings about the state of digital access:

- One in five American adults does not use the internet. Senior citizens, those who prefer to take our interviews in Spanish rather than English, adults with less than a high school education, and those living in households earning less than $30,000 per year are the least likely adults to have internet access.

- Among adults who do not use the internet, almost half have told us that the main reason they don’t go online is because they don’t think the internet is relevant to them. Most have never used the internet before, and don’t have anyone in their household who does. About one in five say that they do know enough about technology to start using the internet on their own, and only one in ten told us that they were interested in using the internet or email in the future.

- The 27% of adults living with disability in the U.S. today are significantly less likely than adults without a disability to go online (54% vs. 81%). Furthermore, 2% of adults have a disability or illness that makes it more difficult or impossible for them to use the internet at all.

- Though overall internet adoption rates have leveled off, adults who are already online are doing more. And even for many of the “core” internet activities we studied, significant differences in use remain, generally related to age, household income, and educational attainment.

The ways in which people connect to the internet are also much more varied today than they were in 2000. As a result, internet access is no longer synonymous with going online with a desktop computer:

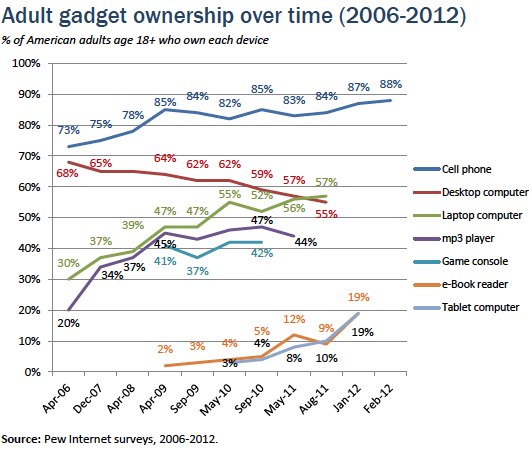

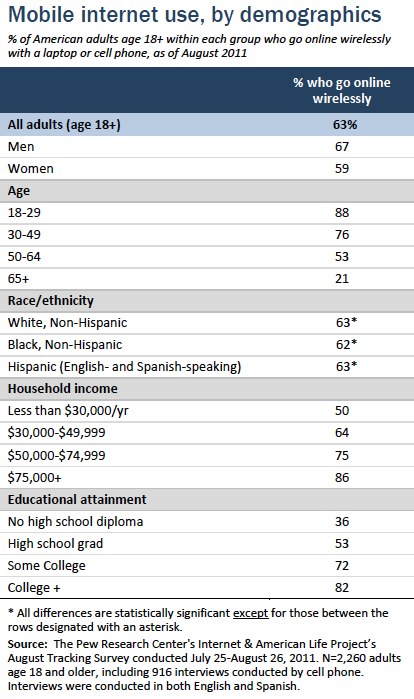

- Currently, 88% of American adults have a cell phone, 57% have a laptop, 19% own an e-book reader, and 19% have a tablet computer; about six in ten adults (63%) go online wirelessly with one of those devices. Gadget ownership is generally correlated with age, education, and household income, although some devices—notably e-book readers and tablets—are as popular or even more popular with adults in their thirties and forties than young adults ages 18-29.

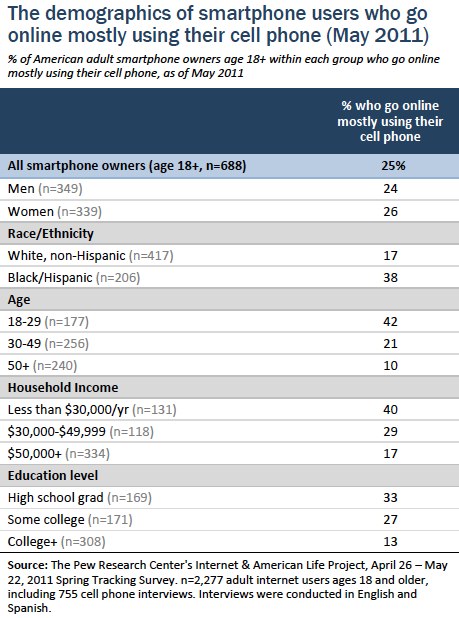

- The rise of mobile is changing the story. Groups that have traditionally been on the other side of the digital divide in basic internet access are using wireless connections to go online. Among smartphone owners, young adults, minorities, those with no college experience, and those with lower household income levels are more likely than other groups to say that their phone is their main source of internet access.

- Even beyond smartphones, both African Americans and English-speaking Latinos are as likely as whites to own any sort of mobile phone, and are more likely to use their phones for a wider range of activities.

The primary recent data in this report are from a Pew Internet Project tracking survey. The survey was fielded from July 25-August 26, 2011, and was administered by landline and cell phone, in English and Spanish, to 2,260 adults age 18 and older. The margin of error for the full sample is ±2 percentage points. For more information about this survey and others that contributed to these findings, please see the Methodology section at the end of this report.

Internet adoption over time

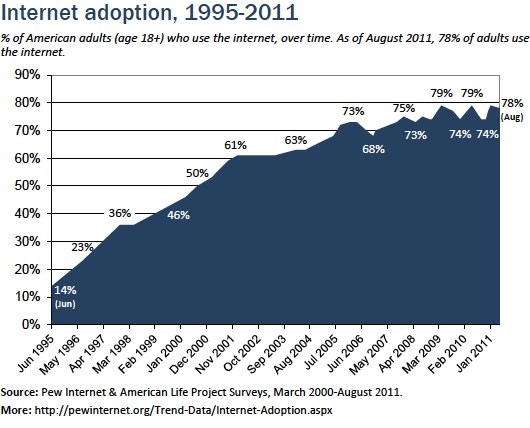

In 1995, only about one in 10 adults in the U.S. were going online.21 As of August 2011, the U.S. internet population includes 78% of adults (and 95% of teenagers).22 Certain aspects of the current internet population still strongly resemble the state of internet adoption in 2000, when one of Pew Internet’s first reports found that minorities, adults living in households with lower incomes, and seniors were less likely than others to be online. “Those who do not use the Internet often do not feel any need to try it, some are wary of the technology, and others are unhappy about what they hear about the online world,” the report concluded.23

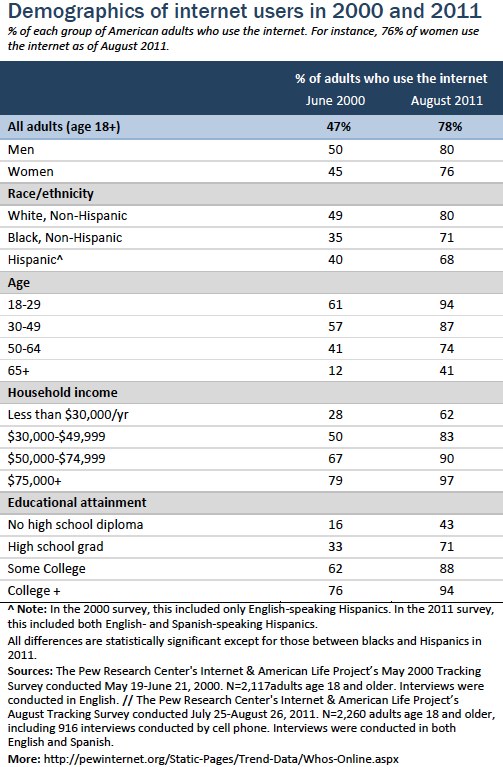

As of 2011, internet use remains strongly correlated with age, education, and household income, which are the strongest positive predictors of internet use among any of the demographic differences we studied. Yet while gaps in internet adoption persist, some have narrowed in the past decade—as shown in the table below.

The internet access gap closest to disappearing is that between whites and minorities. Differences in access persist, especially in terms of adults who have high-speed broadband at home, but they have become significantly less prominent over the years24–and have disappeared entirely when other demographic factors (including language proficiency) are controlled for.

Ultimately, neither race nor gender are themselves part of the story of digital differences in its current form. Instead, age (being 65 or older), a lack of a high school education, and having a low household income (less than $20,000 per year) are the strongest negative predictors for internet use. Our survey in the summer of 2011 was also offered to respondents in both English and Spanish; those who chose to take the survey in Spanish were also notably less likely to use the internet than those who chose English.

Yet even groups that have persistently had the lowest access rates have still seen significant increases over the past decade. In 2000, for instance, we found that there existed “a pronounced ‘gray gap’ as young people go online and seniors shun the internet.” Adults age 65 and older are still significantly less likely to use the internet than other groups, but now 41% of them use the internet. In 2000, over five times as many adults under 30 used the internet as did adults 65 and older, but as of 2011 young adults’ adoption levels are only a little over twice that of the 65-and-over age group.

Along with age, educational attainment represents one of the most pronounced gaps in internet access. Some 43% of adults who have not completed high school use the internet, versus 71% of high school graduates—and 94% of college graduates. Household income is also a strong predictor of internet use, as only six in ten (62%) of those living in households in the lowest income bracket (less than $30,000 per year) use the internet, compared with 90% of those making at least $50,000-74,999 and 97% of those making more than $75,000.25 Educational attainment and household income continue to be strongly correlated not only with internet adoption, but also with a wide range of internet activities and ownership of a number of devices.

Why one in five American adults does not use the internet

Back in 2000, a majority of adults did not use the internet and many non-users felt that that the internet was “a dangerous thing”—54% believed this, especially seniors and those with less than a high school education. Some 39% said that internet access is too expensive (particularly young adults under age 30, Hispanics, and those with less than a high school education), and 36% expressed concern that the internet “is confusing and hard to use,” especially those with a high school education or less.26

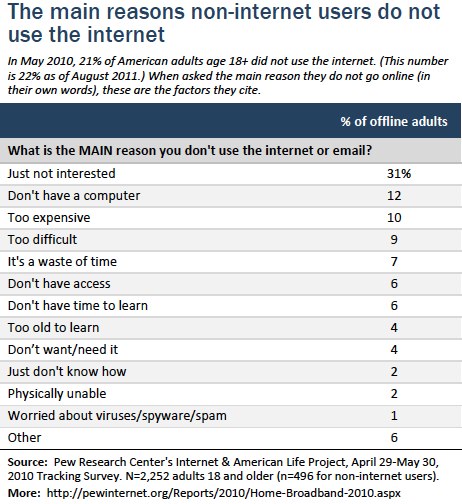

More recent research by the Pew Internet Project has shown that among current non-internet users, almost half (48%) say the main reason they don’t go online now is because they don’t think the internet is relevant to them—often saying they don’t want to use the internet and don’t need to use it to get the information they want or conduct the communication they want. About one in five (21%) mention price-related reasons, and a similar number cite usability issues (such as not knowing how to go online or being physically unable to). Only 6% say that a lack of access or availability is the main reason they don’t go online. 27

Most of these non-users have never used the internet before, and don’t have anyone in their household who does. About one in five (21%) say that they know enough about technology to start using the internet on their own, and only one in ten told us that they were interested in using the internet or email in the future.

Why four in ten American adults do not have a high-speed broadband connection at home

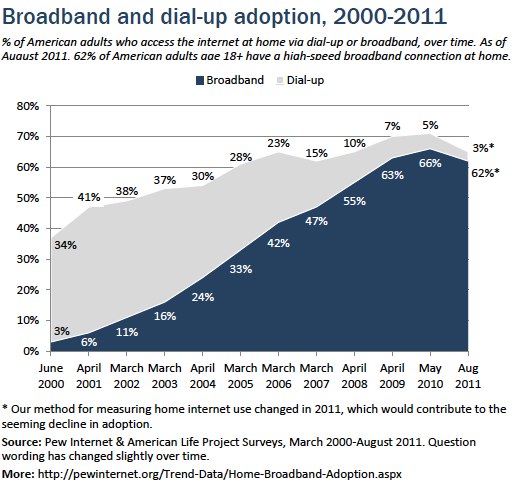

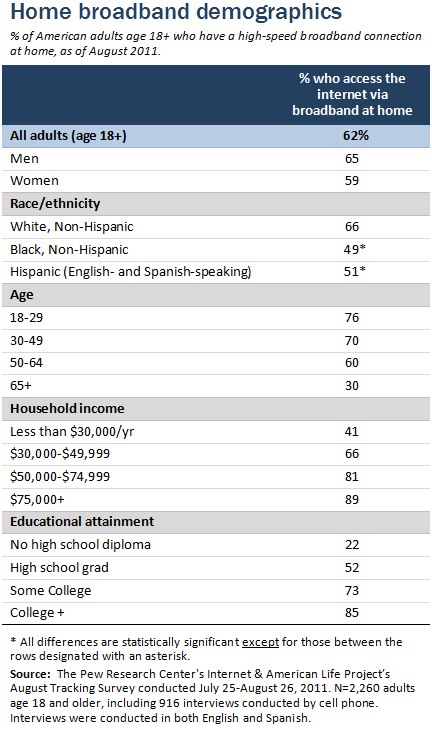

In February 2001, when about half of adults were online, only 4% of American households had broadband access; as of August 2011, about six in ten American adults (62%) have a high-speed broadband connection at home.28 Men are more likely than women to have home broadband, and whites are more likely than minorities. We also see clear patterns in home broadband adoption by age, household income, and education.

Having broadband strongly affects how one uses the internet, especially as multimedia elements such as video become more and more popular. Even back in 2002 we found that dial-up users take part in an average of 3 online activities per day, while broadband users take part in 7.29

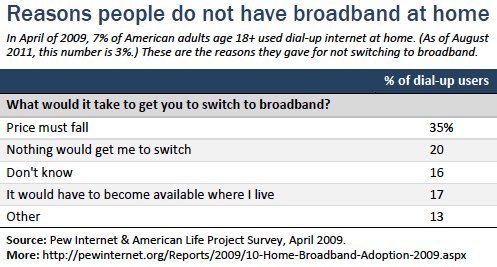

In the spring of 2009, we asked adults who had dial-up internet what it would take for them to switch to a broadband connection at home. A plurality (35%) said the price would have to fall, and 17% said it would have to become available where they live. One in five (20%) said nothing would get them to change.30

By 2010, while national adoption had slowed, growth in broadband adoption among African Americans jumped well above the national average, with 22% broadband adoption growth since the previous year. 31 Even with these gains, however, minorities are still less likely than whites to have home broadband overall. And foreign-born and Spanish-dominant Latinos trail not only whites but also native and English-speaking Latinos. In our August 2011 survey, 62% of all American adults have high-speed internet access at home, including two thirds (66%) of whites and roughly half of African Americans (49%) and Hispanics (51%).

However, as with internet adoption in general, the most persistent demographic differences in home broadband access continue to center around age, household income, and educational attainment. Looking at the groups with the lowest levels of home broadband access, we see adoption levels of 22% for adults who have not completed high school, 30% for seniors age 65 and older, and 41% for those who live in households making less than $30,000 per year. This is compared with 85% of college graduates, 76% of adults under age 30, and 89% of those making at least $75,000 per year.

Americans living with a disability and their internet profile

Finally, there is one difference in internet access that does not often show up in standard demographic tables, and that is the one facing the roughly one in four adults in the United States (27%) who live with a disability that interferes with activities of daily living.32

There are many factors associated with disability that are generally associated with lower internet use—such as being older, being less educated, and living in a lower-income household. When we control for all of these demographic factors, however, we still find that living with a disability in and of itself is negatively correlated with the likelihood that someone has internet access. Some 54% percent of adults living with a disability use the internet, compared with 81% of adults without a disability.

High-speed internet access is also an issue. People living with disability, once they are online, are also less likely than other internet users to have home broadband or wireless access. For instance, 41% of adults living with a disability have broadband at home, compared with 69% of those without a disability.

Finally, a disability or illness itself might be a factor in preventing internet use; 2% of American adults say they have a disability or illness that makes it more difficult—or impossible—for them to use the internet.

Internet activities: Those already online are doing more

While internet adoption has been more or less stable over the past few years, there has been significant growth in the activities internet users engage in once they are online. As a result, the gap in technical experience—and general understanding of the internet—between online adults and offline adults is increasing.

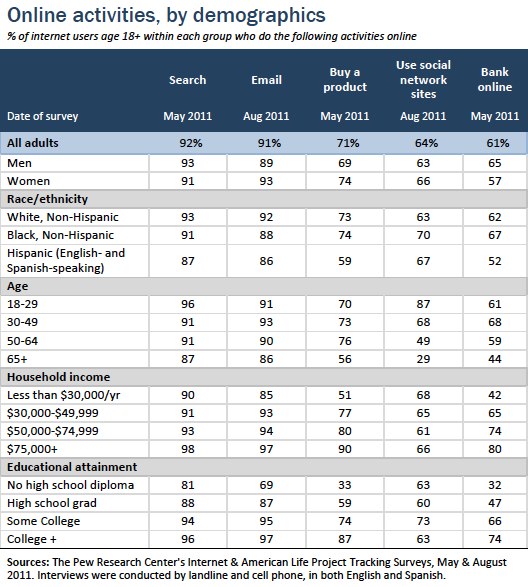

Email and search remain the backbone of the internet (roughly six in ten online adults engage in each of these activities on a typical day), but other activities are becoming ubiquitous as well. Using social networking sites, an activity once dominated by young adults, is now done by 65% of internet users—representing a majority of the total adult population. For the following “core” internet activities, which also include online shopping and online banking, the main gaps in use are related to age, household income, and educational attainment.

Email and search

Since the Pew Internet Project began measuring adults’ online activities in the last decade, email and search have consistently ranked as the most popular. In fact, they remain nearly universal among adult internet users—with a few exceptions.33 Women, for instance, are somewhat more likely than men to use email to communicate, mirroring a trend that we have seen around other online communication activities.34 And young adults under age 30 are more likely than adults age 65 and older to use search engines to find information. Both activities also have a fairly strong correlation with education and income, although there are no significant differences among different groups for either activity by race or ethnicity.

Online commerce: Banking and shopping

Online banking is a relatively common activity online: 61% of adult internet users do it, making it about as popular an activity as using social networking sites. However, as with buying products online, we do see a few noticeable differences among demographic groups, especially in terms of age, household income, and education. Most strikingly, adults age 65 and older are significantly less likely than other age groups to do any banking online. Additionally, those with at least some college (including college graduates) are more likely to use online banking than those with a high school diploma or less, and those in households making less than $30,000 per year are the income bracket least likely to use online banking, while those in households making more than $75,000 per year are most likely. Online banking is also more popular with online men than with online women. There are no differences by race or ethnicity.

Purchasing products online is also significantly less popular with adults over age 65. Those who have not completed high school and those in households making less than $30,000 per year are less likely to buy products online, while college graduates and those in households making more than $75,000 are more likely to do this. Online Hispanics are also somewhat less likely to make online purchases than whites or African Americans. There are no significant differences between internet users by gender.

Social networking site usage

Though one of the newer online activities the Pew Internet Project studies,35 as of 2011 social networking sites are used by 65% of all internet users—half of all American adults.36 Among internet users, we see a very strong correlation in use with age, as some 87% of internet users under 30 use these sites, compared with less than a third (29%) of those 65 and older. However, though their overall numbers are still relatively low, older adults have represented one of the fastest-growing segments of the social networking site-using population.37 This growth may be driven by several factors, some of which include the ability to reconnect with people from the past, find supporting communities to deal with a chronic disease, and connect with younger generations.38

Other groups that are particularly likely to use social networking sites are adults with at least some college experience (who have not yet graduated) and parents with minor children living at home. There are currently no major differences in overall social networking site usage by gender, race, or household income.

The power of mobile

Currently, 88% of American adults age 18 and older have a cell phone, 57% have a laptop, 19% own an e-book reader, and 19% have a tablet computer; about six in ten adults (63%) go online wirelessly with one of those devices. Gadget ownership is generally correlated with age, education, and household income, although some devices—notably e-book readers and tablets39—are as popular or even more popular with adults ages 30-49 than those under 30.

As our research has documented the rise of mobile internet use, we have also noticed a “mobile difference”: Once someone has a wireless device, she becomes much more active in how she uses the internet–not just with wireless connectivity, but also with wired devices. The same holds true for the impact of wireless connections and people’s interest in using the internet to connect with others. These mobile users go online not just to find information but to share what they find and even create new content much more than they did before.40

A closer look at smartphones

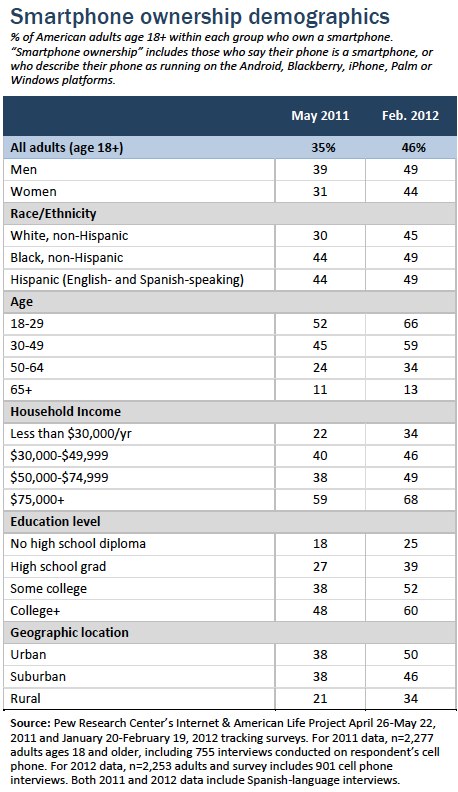

Some 46% of American adults have a smartphone, defined as adults who either say their phone is a smartphone when asked, or who describe their phone as running on the Android, Blackberry, iPhone, Palm or Windows platforms.41 Two in five adults (41%) own a cell phone that is not a smartphone, which means that smartphone owners are now more prevalent within the overall population than owners of more basic mobile phones.

As we found in our May 2011 study of smartphone adoption, several demographic groups have higher than average levels of smartphone adoption, including groups that traditionally have higher rates of tech adoption in general: the financially well-off, the well-educated, and adults under age 50.

Additionally, we see no significant differences in use between whites and minorities. Both African-Americans and Latinos have overall adoption rates that are comparable to the national average for all Americans (smartphone penetration is 49% in each case, just higher than the national average of 46%).

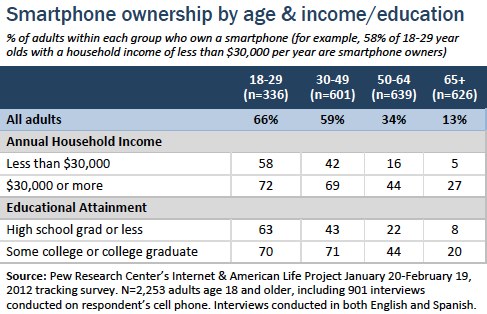

Young adults continue to have higher-than-average levels of smartphone ownership regardless of income or educational attainment.42 Younger adults under age 30 with a high school diploma or less are significantly more likely to own a smartphone than adults 50 and older who have attended college. Similarly, adults under age 30 who live in households making less than $30,000 per year are still more likely to own a smartphone than those over age 50 in higher income brackets.

Previously, in May of 2011, we found that young adults, minorities, those with no college experience, and those with lower household income levels who owned smartphones were more likely to say that their phone was their main source of internet access.43 Many of “cell mostly” internet users have other ways to connect to the internet—most have a desktop or laptop computer at home, for instance. But about one third of these adults do not have a traditional high-speed broadband connection at home. For them, their smartphone is a way for them to access the online world.

How organizations are harnessing the power of mobile

Many organizations, especially health-related organizations, are turning to mobile strategies to address the digital divide and reach underserved populations. Cell phones are especially powerful because they are so widespread throughout the U.S. population; while certain groups, such as young adults, certainly have higher adoption rates than others, cell phones are still relatively ubiquitous throughout all age groups, income levels, and racial and ethnic groups.

One example of a mobile outreach program is text4baby (www.text4baby.org), a free service that provides free prenatal advice and information to pregnant women and new moms, pegged to the due date of the child, in English or Spanish. The service includes everything from reminders about prenatal check-ups to advice and resources about nutrition, exercise, car seat safety, breastfeeding, and other topics.

For more examples, see Susannah Fox’s presentation, “The Power of Mobile”: https://legacy.pewresearch.org/internet/Commentary/2010/September/The-Power-of-Mobile.aspx

Mobile activities

Beyond smartphones, our surveys have found that both African Americans and English-speaking Latinos are more likely to own any sort of mobile phone than whites. Foreign-born Latinos do trail their native-born counterparts in cell phone ownership, but this gap is significantly smaller than the gap in internet use between these groups.

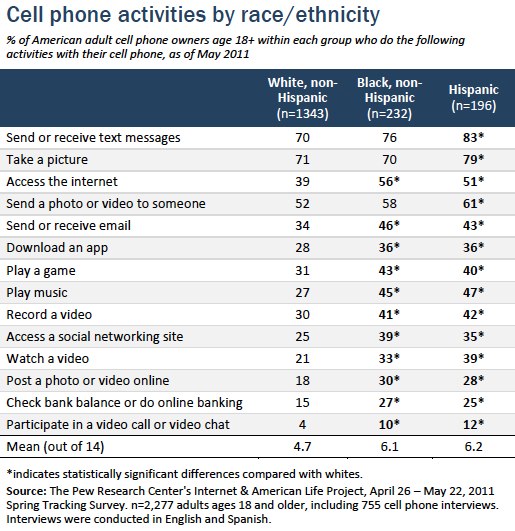

Over time, we’ve seen that minority groups use a much wider range of their cell phones’ capabilities compared with white cell phone owners.44 The full list is available in the table below.