What is associated with the size of discussion networks?

There is a great concern that over the last twenty years the size and diversity of Americans’ core networks have declined; that core networks are increasingly centered on a small set of relatively similar social ties at the expense of larger more diverse networks. Is there evidence to suggest that newer information and communications technologies (ICTs) such as the internet and mobile phone are responsible for a trend toward social isolation?

What is associated with the size of discussion networks?

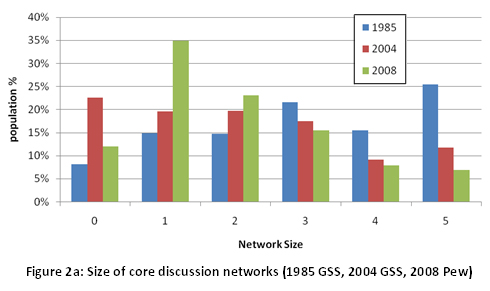

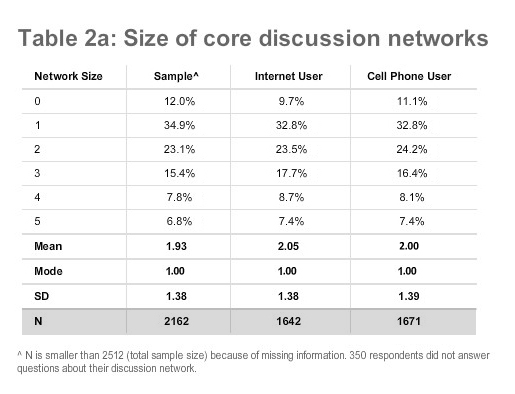

Those people with whom we discuss “important matters” are our core discussion network. The Pew Internet Personal Networks and Community survey found that the average American has about two discussion confidants (1.93), which is similar to the mean of 2.06 from the 2004 GSS (Table 1a). However, the Pew Internet survey found that a much smaller proportion of the population reported having no discussion partners than the 2004 GSS survey: The Pew Internet survey found that 12.0% of Americans have no discussion partners, compared to the 22.5% recorded in the 2004 GSS. Our findings also show that the modal respondent – the most common response – lists one confidant, not zero, as was found in the 2004 GSS analysis.

Our findings suggest that social isolation may not have increased over the past twenty years. Our finding that only 12.0% of Americans have no discussion partners is relatively close to the 8.1% that was found in the 1985 GSS (Table 1a), so the number of Americans who are truly isolated has not notably changed. At the same time, the Pew Internet survey supports the GSS evidence that the average number of discussion partners Americans have is smaller now than it was in the past. Our data indicate that the average American has 1.93 discussion partners, a figure similar to the 2.06 found in the 2004 GSS, and a full one tie smaller than the 2.98 found in 1985.

ICT users do not suffer from a deficit of discussion partners.

When the Pew Internet Personal Networks and Community survey was conducted (July 9-August 10, 2008), 77% of the U.S. adult population used the internet, and 82% owned a mobile phone. Contrary to concerns that use of ICTs may be associated with an absence of confidants, no evidence was found that internet users have smaller discussion networks. Instead, our data indicate that, on average, internet and mobile phone users appear to be less likely to have no confidants and tend to have more people with whom they discuss important matters.

- 12% of all Americans report no discussion partners, but only 10% of internet users and 11% of mobile phone users have no discussion ties.

- 30% of the American population has discussion networks of three or more people compared to 34% of internet and 32% of mobile phone users.

Mobile phone use, and use of the internet for sharing digital photos, and for instant messaging are associated with larger discussion networks.

There is considerable variation across people in terms of their demographic characteristics, and in how they use ICTs. Regression analysis is a statistical technique that allows us to identify what specific characteristics are positively or negatively associated with an outcome, such as the number of discussion ties. To be sure that the relationship we have identified cannot be explained by other factors, and so that we can look at different types of online activity, we use regression to identify the statistically significant factors that are associated with the size of core discussion networks.11 The results of this regression analysis, listed in Appendix D: Regression Tables as Table 1, show that a number of demographic factors are independently linked with the size of discussion networks. Consistent with prior research [12, 13], the Pew Internet study revealed the following:

- Education attainment is associated with having a larger number of people with whom one can discuss important things. The more formal schooling people have, the bigger their networks. For example, compared to a high school diploma, an undergraduate degree is associated with approximately 14% additional discussion partners.

- Those who are a race other than white or African-American have significantly smaller discussion networks; about 14% smaller.

- Women have about 13% more discussion ties than their male counterparts.

Regression analysis also confirmed the relationship between ICT use and core discussion networks while identifying specific types of technology use that are positively associated with the number of discussion partners.

» Those who own a mobile phone average 12% more confidants.

» Simply having access to the internet, as well as frequency of internet use has no impact on core discussion network size, what matters is what people do online.

- Uploading photos online to share with others is associated with having 9% more confidants.

- Those who use instant messaging have 9% additional confidants.

- Other activities, such as using a social networking service (e.g., Facebook, LinkedIn, and MySpace) or maintaining an online journal or blog have no relationship to the number of confidants.

Example: An average white or African-American, female with an undergraduate university degree, who has a mobile phone, uses the internet to share photos by uploading them to the internet, and uses instant messaging has 2.55 confidants. This compares to 1.91 ties for an average woman of the same race and education who does not upload photos online, use instant messaging, or own a mobile phone. In this example, use of ICTs is associated with a core discussion network that is 34% larger.

Not only is internet and mobile phone use not associated with having fewer confidants, but the compound influence of ICT use has a very strong relationship to the size of core discussion networks in comparison to other important demographic, such as race, gender, and education. In other words, ICT use can have a relatively big effect on the size of people’s core networks.

How is internet use and mobile phone use related to the composition of core discussion networks?

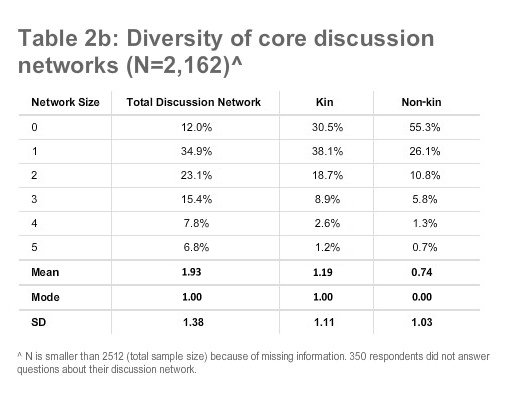

Discussion networks include people from a variety of settings. They may include spouses and household members, extended family, workmates, neighbors, and other friends. There is abundant evidence that having a diverse discussion network made up of people from a variety of settings, such as neighborhood and community contexts, brings people benefits by ensuring them access to different types of social support and exposure to diverse ideas and opinions. One way to look at the diversity of a discussion network is to separate kin and non-kin. People tend to have more things in common, including interests, values, and opinions with family than they do with people from other settings.

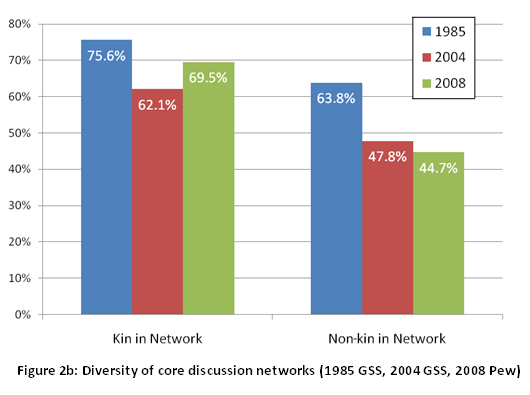

The Pew Internet Personal Networks and Community survey found that most people discuss important matters with members of their family (70%), but less than half of all Americans (45%) have a confidant that is not a family member. The proportion of the population found to have at least one non-kin confidant is similar to the 47.7% found in the 2004 GSS (Table 1b).

Mobile phone users, and internet users who use social networking services, rely more on family members to discuss important matters.

Family members are an important source of broad social support [2]. Regression analysis was used to identify demographic factors associated with the number of family ties who are confidants. The analysis, reported in Appendix D as Table 2, shows that:

- Women tend to rely on a greater number of kin as confidants – on average 21% additional family members.

- Those who are married or cohabitating with a partner tend to discuss important matters with about 28% more kinship ties.

- More years of education is associated with a larger number of kin confidants; about 3% more for each year of education.

The relationship between number of kin and participation in various internet and mobile activities was also tested.

- Those who use a mobile phone have about 15% more family members with whom they discuss important matters.

- Use of a social networking website is associated with a kinship discussion network that is about 12% larger.

Example: An average female, with a high school diploma, and who is married has 0.94 core discussion members who are also kin. A demographically similar woman who owns a cell phone and also uses a social networking website has an average of 1.21 family members who are core confidants. In this example, ICT use is associated with a core network that has 29% additional kinship ties.

Married internet users are less likely to rely exclusively on their partner to discuss important matters, especially if they also use instant messaging.

Like other family ties, a spouse can be an important source of social support. But those who rely exclusively on their spouse/partner as their only confidant may have limited exposure to diverse opinions, issues, and points of view that come from discussing important matters with a larger, more diverse network. In comparison to other types of social ties, spouses are particularly likely to be similar in many ways to their mates and that limits the extra information and experiences a spouse can contribute.

Looking only at married and cohabitating couples in the survey, the Pew Internet Personal Networks and Community survey shows that 19.3% of those who live with a partner rely exclusively on the partner to discuss important matters; this compares to a smaller number – 13.9% – found in the 2004 GSS (Table 1b).

Regression analysis was used to explore the relationship between different demographic characteristics and different types of ICT use to predict the odds of having a spouse as only confidant.12 The results, reported in Appendix D as Table 3, show among other things, that internet users are more likely than others to have someone in addition to a spouse as a discussion partner:

- The odds that a women relies solely on her partner to discuss important matters are 43% less than they are for men.

- Having children under the age of 18 at home increases the odds of a partner being the only discussion confidant by 52%.

- The likelihood of someone who is African-American limiting the discussion of important matters to a spouse/partner are 54% less than they are for white Americans.

- The likelihood of someone who is Hispanic relying exclusively on a spouse to discuss important matters is 54% lower than those who are not Hispanic.

- The likelihood of an internet user having a spouse/partner who is their only confidant is 37% lower than non-users.

- In addition, those who use the internet for instant messaging are even less likely than other internet users to have a spouse as their only confidant. Instant messaging users are 35% less likely than other internet users, or 59% less likely than non-internet users, to have a spouse as their only confidant.

Example: The probability that an average white (non-Hispanic) woman who has children at home relies exclusively on her spouse to discuss important matters is about 46%. However, the probability of a similar woman who uses the internet and instant messaging relying exclusively on her spouse for important matters is only 26%.

Internet users have more diverse core discussion networks.

There is considerable scholarship showing that people who have a core discussion network that includes non-kin, such as workmates or neighbors, improve their access to a broad range of support and information. Regression analysis shows there are a number of demographic factors associated with having non-kin discussion partners. The results, reported in Appendix D as Table 4, indicate:

- The likelihood of having at least one non-kin discussion tie is 5% higher for each year of formal education.

- Married and cohabitating couples have odds of having at least one non-kin discussion tie that are 50% less than those who live alone.

Example: The probability of someone who is married, with a high school education having at least one non-family member in their discussion network is about 21%. The probability of someone who is married, with an undergraduate degree having a non-kin discussion partner is higher, at 24%. A single person with the same level of university education has a 39% chance of discussing important matters with someone who is not a family member.

Internet users are more likely to have non-kin in their discussion network. Mobile phone users are no more or less likely to discuss important matters with non-kin.

- The odds that an internet user has a confidant outside of his/her family are 55% higher than non-users.

- Frequency of internet use, the use of a mobile phone, instant messaging, uploading photos online, blogging, and using social networking websites have no notable relationship with the likelihood of having non-kin discussion partners.

Example: The probability of someone who is married, with a high school education, who uses the internet having at least one non-family member in his discussion network is about 29%. This compares with the 21% probability for a demographically similar person who does not use the internet.

Frequent internet use and blogging are associated with racially diverse core discussion networks.

This survey found that about 24% of Americans discuss important matters with someone who is of a different race or ethnicity from themselves.13

Regression analysis, reported as Table 5 in Appendix D, finds that minorities are most likely to have at least one cross-race or ethnicity confidant.

- The odds that an African-American has a discussion partner of another race or ethnicity are 2.13 times higher than they are for white Americans, 4.52 times more likely for other-race Americans, and 4.41 times more likely for Hispanic Americans.

A number of other demographic factors were also associated with the likelihood of having a cross-race or ethnicity confidant.

- The likelihood of a female having a confidant of another race or ethnicity is 27% lower than for a male.

- The odds are 28% lower that someone who is married will have a cross-race or ethnicity discussion partner.

Very specific ICT activities are associated with the racial and ethnic diversity of core discussion networks.

- Frequent home internet users – those who use the internet from home at least a few times per day – are 53% more likely to have a cross-race or ethnicity confidant, compared to those who use the internet less often.

- The odds of having a cross-race or ethnicity confidant are 94% higher for those who maintain a blog.

Example: The probability that an African-American male who is married discusses important matters with someone of another race is about 25%. The probability that a white American male of the same marital status has a cross-race discussion tie is only 14%. If a similar white American was a frequent home internet user and maintained a blog, the probability that he would have a discussion confidant of another race would increase to 32%.

Online photo sharing is associated with diverse political discussion partners.

Among those who identify themselves as a Republican or a Democrat, 19% reported that they discussed important matters with someone affiliated with the major opposition political party.14 We found, and reported in Table 6 of Appendix D, that age was associated with politically diverse discussion networks – the older the person, the more likely his or her network was politically diverse – whereas being nonwhite was not associated with having a diverse network. Only one internet activity was associated with having a politically diverse discussion network.

- Those who uploaded photos to share online were 61% more likely to have a cross-political discussion tie.

- Other forms of internet use, frequency of use, and use of a mobile phone are not associated with the likelihood of discussing important matters with someone of a different political party.

Example: The probability of a 45-year-old, white American who considers themselves to be a Democrat having someone who considers themselves a Republican as a confidant is about 27%. However, if that 45-year-old, white American uploads photos to share with others online, the probability of having a cross-party tie increases to 37%. An African-American with a similar demographic and internet use profile would have only a 17% probability of a cross-political tie.

Some internet activities, such as photo sharing, provide opportunities for exposure and interaction with diverse others who in turn contribute to political diversity within core discussion networks. However, it is also possible that those with more politically diverse networks are more likely to take the opportunity to share photos online. It is also recognized that most people believe they are more similar to their network members than they really are. Therefore, an activity like sharing photos online may simply improve the flow of information within core discussion networks, eliminating a sense of sameness that actually never existed. Those who share photos online may either have more politically diverse networks, or they may have a more accurate sense of the political tendencies of their core discussion partners.

Has the meaning of “discuss” changed in the age of the internet?

Participants in our survey, as well as those in the 1985 and 2004 General Social Surveys, were asked to provide a list of people “with whom [they] discussed important matters over the last six months.” Although this methodology has been used in the past to measure core networks, the continued use of this question to compare networks over time assumes that there has not been a shift in how people understand the concept of “discussion” [13]. For example, the rise of the internet as a part of everyday life might have changed how many people “discuss” important matters. When asked about those with whom they “discuss,” people may be more likely to think of those whom they frequently see in person. If, as a result of the internet, some important discussion now takes place online, respondents may omit mentioning important and supportive ties to those whom they see less frequently in person but with whom they often interact, partially or primarily online.

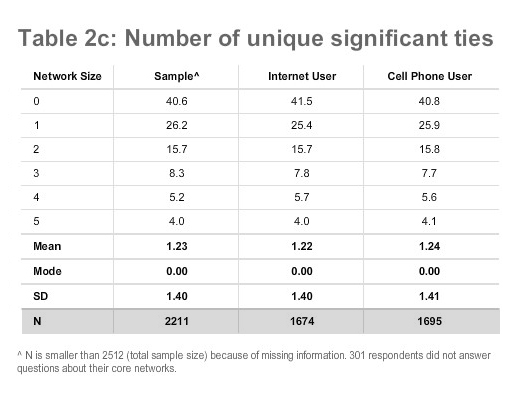

To test the possibility that Americans’ understanding of “discuss” has changed, people in the Pew Internet survey were asked a second question about their social networks. After asking them to name the people with whom they “discuss important matters,” we asked them to list those who are “especially significant” in their life. This is another way to get people to focus on their important ties. When they answered this question, the second list could contain the same or different people as those mentioned in the first question that asked about discussion partners. Prior research has identified a high degree of network overlap between responses to these two types of questions [9]. If the meaning of “discuss” has changed over time, then ICT users’ answers to the second question would be different from non-users’ answers. That is, internet and cell phone users would be more likely than non-users to have people in their life who are “especially significant,” but with whom they do not “discuss” important matters.

When the lists of “discuss” and “significant” ties are combined, they represent a list of “core network members” – a list of a person’s strongest social ties. If internet users list more unique new names that are “significant” in their life that are not part of their “discussion” network, such evidence would suggest that internet users do not interpret a question that asks with whom they “discuss important matters” in the same way as other people. If this is the case, it may explain why previous research suggests that there has been an increase in social isolation in America over the last twenty years [13].

Internet use has not changed the meaning of “discuss”

There is considerable overlap in most people’s network of “discussion” confidants and those they consider to be “especially significant” in their lives. However, in this survey, 26% of people listed one, 16% listed two, and 18% listed between three and five people who were especially significant in their lives, but with whom they did not “discuss” important matters. Contrary to the argument that internet or cell phone users might interpret “discuss” in a way that is different than other people, they did not list a larger number of new names as “significant” in comparison with the rest of the population.

A regression analysis, reported as Table 7 in Appendix D, explores the likelihood of a person listing at least one significant tie that they did not list as a discussion partner finds no meaningful variation based on internet use. Internet and mobile phone use, frequency of internet use, and no single internet activity that we measured predicted the likelihood of having a “significant” tie that was not also a discussion tie.

This evidence suggests that the introduction of the internet has not had a significant influence on how people respond to a question that asks them to list those “with whom [they] discuss important matters.” That is, internet users are not withholding names of core network members in response to this question simply because of the changing nature of how discussion is mediated.

Are Americans truly socially isolated?

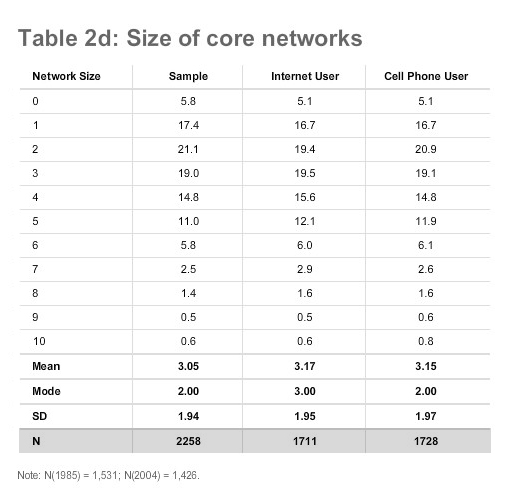

Core discussion networks are one segment of a broader network of strong ties that provide most of people’s social support. This survey asked people to list those with whom they “discuss important matters” and to provide an additional list of names of those who are especially “significant” in their lives. The list of significant ties could contain the same or different people as those with whom a person discusses important matters. Combined, these lists of names represent a person’s “core network” – those people who provide a large segment of everyday social support.

Few Americans are socially isolated, and the socially isolated are no more likely to be internet or mobile phone users.

The results of the Pew Internet survey show that the average person has three core network members. Only a very small proportion of the population is truly socially isolated (5.8%), with no one with whom they either discuss important matters or consider to be especially significant in their lives.

- On average, internet and mobile phone users are no more likely to be socially isolated than the general population (5% of cell phone users have no core ties compared to 6% of the general population). Internet users and mobile phone users are slightly more likely to report that they have a core network of three or more ties; 56% of the general population has a core network of three or more ties compared to 59% of internet users and 57% of mobile users.

Mobile phone users and those who use the internet for instant messaging have larger core networks.

As with our analysis of discussion networks, regression analysis allows us to explore the true relationship between ICT use, demographic characteristics, and network size.

As with discussion networks, men, those with few years of formal education, and those of races other than white or African-American tend to have smaller core networks.

The regression, reported in Appendix D as Table 8, shows that the ICTs associated with a large core network are more specific than they are for discussion networks. Larger core networks are associated with the use of a mobile phone and use of the internet for instant messaging. Internet use is otherwise not influential on the size of core networks.

- Those with a mobile phone have core networks that are about 12% larger.

- Those who use instant messaging tend to have core networks that are about 11% larger.

Frequent internet use, and other internet activities, such as blogging, the use of social networking websites, and sharing photos online have no influence on the size of core networks.

Example: The average 40-year-old, white or African-American, male with an undergraduate university degree, who has a mobile phone, and uses instant messaging, has a core network of about three people (3.11). A male of the same age, race, and education, who does not use a mobile phone and never uses IM typically has a core network that is about 19% smaller (2.51 ties).

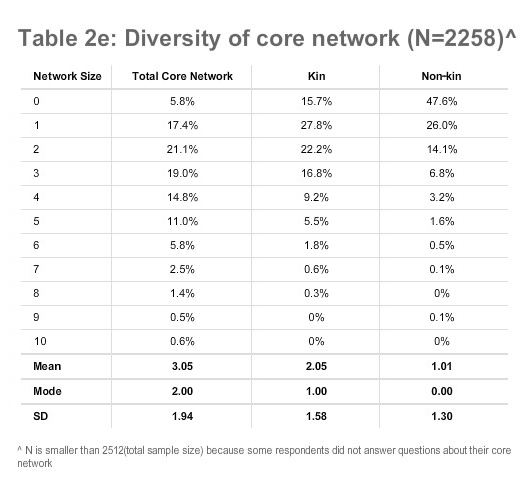

Only half of Americans have anyone in their core network who is not a family member.

Core networks include not only close confidants, but those who provide much of the personal support required for daily life and dealing with emergencies. As with discussion networks, a diverse core network, consisting of family members and people from other settings, such as the workplace and neighborhood, is important to ensure access to different types of social support.

Results show that 84% of Americans have a family member in their core network, but only one-half of Americans (52%) have non-kin as members of their core network.

A larger number of non-kin within core networks is associated with general internet use, frequent at home use, sharing photos online, using instant messaging, and owning a mobile phone.

Regression analysis, Table 9 in Appendix D, confirms that having a larger number of non-kin as part of a core network is associated with owning a mobile phone, spending time online, using instant messaging, uploading photos to share with others, and frequent at home internet use.

- Those who own a cell phone tend to have 25% more core network members who are not family members.

- Internet users tend to have 15% additional core network ties who are not members of their family.

- Using the internet at home more than a few times per day is associated with an additional 17% more non-kin as part of a core network.

- Those who use the internet for instant messaging have 19% additional non-kin in their core networks.

- Sharing photos online is associated with having a larger core network of non-kin, such that those who upload photos to share with others have 12% more non-kin in their networks.

There are a number of additional demographic factors associated with the number of non-kin that people tend to have in their core network. Education is associated with having a larger number of people who are not family within a core network; on average, four years of additional education is equal to a 14% boost in the number of non-kin within a core network. Those who are married or living with a partner tend to have 31% fewer non-kin, with those with children at home generally have 10% fewer non-kin in their core network.

Example: The average person with an undergraduate degree, who is single with no children, and who is a frequent home internet user, owns a cell phone, uses instant messaging, and shares photos online has a little less than two people (1.64) in his/her core network who are not members of his/her family. A person with the same level of education who does not use the internet or a cell phone averages one fewer person in his/her core network who is not a family member (0.73).

Internet and mobile phone users’ core networks are as stable as non-users.

The average length of time internet and mobile phone users have known core network members who are not members of their family tends to be about the same as for non-users.15 The only demographic factors found to predict network stability was age, with older people having more stable networks (see Table 10 in Appendix D).

How are the internet and mobile phone used to communicate with core network members?

Most studies of how people communicate with members of their core network focus exclusively on in-person contact. This includes the General Social Survey, which, in 2004, asked only one question about interaction with core network members: “How often do network members talk?” This focus privileges a certain type of communication, mainly that which can take place in person or possibly over the telephone. It leaves little room for the possibility that important social contact takes place through other forms of communication, such as postal mail, email, instant messaging, text messaging (SMS), and social networking services.

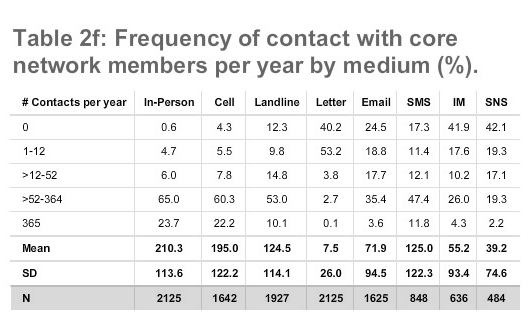

To calculate frequency of contact across various communication platforms we asked participants how many days per month they were in contact with each of their core ties using a variety of media, including face-to-face. We averaged the answers respondents gave across all core ties and extrapolated to a full year of communication activity per core tie.

We found that Americans take advantage of a wide range of media to maintain their core networks and that “talk,” whether in person or over the telephone, is only a fraction of the total supportive exchange between core network members.

- Traditional media: The average person sees each member of their core network 210 days of the year, talks to them using a landline telephone on 125 days, and sends each core network member an average of 8 letters or cards.

- ICTs: If they have a mobile phone, the average person talks to each core network member by mobile phone on 195 days. Email users send messages to each core tie on 72 days of the year. If a person uses text messaging (SMS), on average they send text messages to each core network member on 125 days. Those who use instant messaging contact core ties by IM on 55 days of the year. Of those who use social networking services (SNS), SNS are used to message each core tie an average of 39 days each year.

Distance matters in the choice of communication media.

Research that focuses mainly on in-person contact ignores the fact that face-to-face interaction is just one of a number of methods through which people exchange support [2, 14, 15]. Digital media provide new opportunities for people to maintain contact across distance. In addition, there is clear evidence that digital media are also important in maintaining contact with very local ties. Keith Hampton and Barry Wellman have called this “glocalization” [16] – people use new ICTs to expand their horizons at the same time they use the technology to maintain local ties.

The Pew Internet Personal Networks and Community survey finds that in-person contact, landline telephones, mobile phones, and text messaging (SMS) are used most frequently for contact with local ties and much less frequently with core ties who live at a distance. Cards and letters are used most frequently with core ties at a distance. These media contrast with email, social networking services, and instant messaging, all of which facilitate glocalization (both local and distant ties). They are used almost as frequently to maintain contact with local ties as they are to contact distant core ties.

- The most frequent medium used to maintain contact with core network members is in-person, face-to-face contact. However, in-person contact decreases with distance, from nearly daily contact for those with whom a person shares a home (359/365 days), to less than one-third as often for core ties who live 50-100 miles away (107/365 days).

- Like face-to-face contact, traditional, landline telephone contact is less frequent with core network members who live at a distance, and most frequent with those who live nearby. Core ties who live 50-100 miles away receive less than half as many calls (82/365 days) as those who live on the same block or street (173/365 days).

- Text messaging and short message service (SMS) on mobile phones resemble landline telephone and face-to-face contact. Communication is most frequent among core ties who live nearby – 137/365 days for those who live 1-5 miles away; it drops sharply with core ties who live further away – 69/365 days for those 50-500 miles away.

- Similarly, the use of voice calls on mobile phones is most frequent with those who live nearby (276/365 days for core ties within the same home), and less frequent with distance (138/365 days for core ties 50-100 miles away). However, unlike these other media, contact is less dependent on distance, and frequency of use trails off less steeply.

- Email is used relatively consistently across distance – 81/365 days per year for core ties within 1-5 miles, and 73/365 days for core ties who are 500-3000 miles away.

- Messages sent through social networking services, such as Facebook, tend to resemble email communication. They are used relatively consistently with core ties at all distances – 48/365 days per year for core ties who live 1-5 miles away, and 43 days per year for core ties 500-3000 miles away.

-

Instant messaging (IM) also resembles email and social networking services. Communication with core network members using IM is almost as frequent with those who live locally (72/365 days, 1-5 miles away), as it is with those who live far away (55/365 days for those who live 500-3000 miles away). Postal mail in the form of letters and cards is in sharp contrast with in-person contact. It is the least frequent medium overall and is used most often to communicate with core ties who live furthest away. Core ties who live more than 3,000 miles away receive on average twenty-four cards and letters per year. This compares with the average six cards/letters given to core network members in the same household.

Are core network members our “friends”? The use of social networking services (SNS) in the maintenance of core networks.

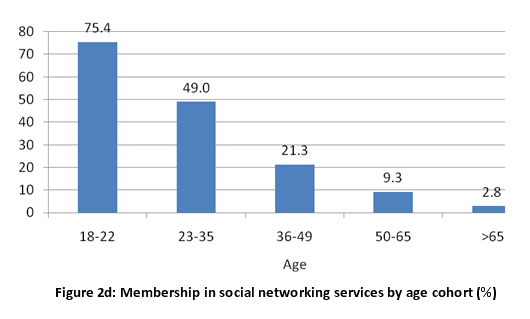

Social networking services, such as Facebook, MySpace, and LinkedIn, provide people with a way to “friend” and then communicate with people who are a part of their social network. We found that 26% of American adults use social networking services, with younger cohorts much more likely to use SNS than older cohorts: 75% of 18-22- year-olds, 49% of 23-35-year-olds, 21% of those who are 36-49, 9% of those who are 50-65, and only 3% of those who are over 65.

Younger users of social networking services are most likely to have influentials as social networking site (SNS) “friends.”

Social network sites (SNS) provide a new way for people to communicate with members of their social network. “Friends” on a SNS can be core network members, weaker social ties, friends of friends, or even near strangers. However, if core network members are listed as “friends” on SNS, it may be possible for those outside of people’s immediate social circle to identify core network members [17]. Core network members often serve as “infuentials” in the decision-making process [4]. If marketers and interest groups can use social networking services to target influentials, they may be able to manipulate an individual’s decision making on a variety of subjects, ranging from consumer products to politics.

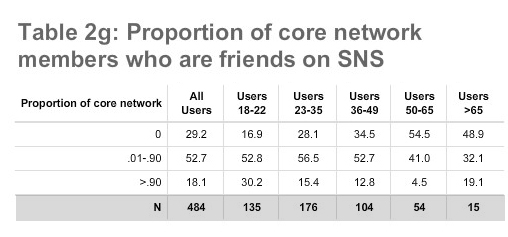

- 71% of all SNS users listed at least one member of their core network as a “friend.”

- 18% of all SNS users listed more than 90% of all their core network members as SNS “friends.”

Younger SNS users were much more likely to list at least one or the majority of their core network members as SNS “friends.”

- 83% of 18-22-year-old SNS users listed at least one core network member as an SNS “friend.”

- The likelihood of listing a core network member as a friend was lower with age, such that only 46% of 50-65-year-old SNS users list at least one core network member as an SNS “friend.”

- 30% of 18-22-year-old SNS users have more than 90% of their core network members listed as SNS “friends.”

- Only 15% of 23-35-year-olds, 13% of 36-49-year-olds, and 5% of 50-65-year-old SNS users list more than 90% of their core network members as SNS “friends.”

These findings suggest that younger cohorts, particularly those in the 18-22 year range, are particularly likely to have a concentration of core network members on social networking services. Although these SNS may benefit from a new form of access to core network members, they may also be particularly open to influence from marketers and lobby groups that use SNS to target influentials as a strategy to manipulate or guide decision making.