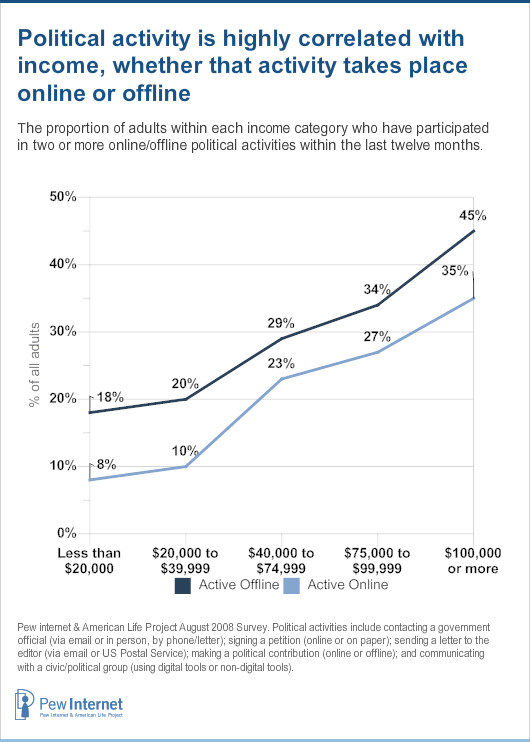

Whether they take place on the internet or off, traditional political activities remain the domain of those with high levels of income and education.

Contrary to the hopes of some advocates, the internet is not changing the socio-economic character of civic engagement in America. Just as in offline civic life, the well-to-do and well-educated are more likely than those less well off to participate in online political activities such as emailing a government official, signing an online petition or making a political contribution.

In part, these disparities result from differences in internet access—those who are lower on the socio-economic ladder are less likely to go online or to have broadband access at home, making it impossible for them to engage in online political activity. Yet even within the online population there is a strong positive relationship between socio-economic status and most of the measures of internet-based political engagement we reviewed.

At the same time, because younger Americans are more likely than their elders to be internet users, the participation gap between relatively unengaged young and much more engaged middle-aged adults that ordinarily typifies offline political activity is less pronounced when it comes to political participation online. Nevertheless, within any age group, there is still a strong correlation between socio-economic status and online political and civic engagement.

There are hints that forms of civic engagement anchored in blogs and social networking sites could alter long-standing patterns that are based on socio-economic status.

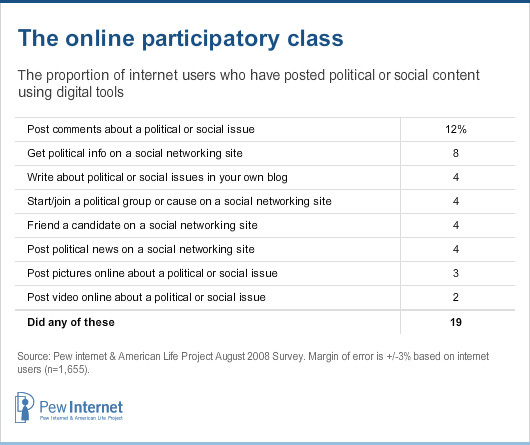

In our August 2008 survey we found that 33% of internet users had a profile on a social networking site and that 31% of these social network members had engaged in activities with a civic or political focus—for example, joining a political group, or signing up as a “friend” of a candidate—on a social networking site. That works out to 10% of all internet users who have used a social networking site for some sort of political or civic engagement. In addition, 15% of internet users have gone online to add to the political discussion by posting comments on a website or blog about a political or social issue, posting pictures or video content online related to a political or social issue, or using their blog to explore political or social issues.

Taken together, just under one in five internet users (19%) have posted material about political or social issues or a used a social networking site for some form of civic or political engagement. This works out to 14% of all adults — whether or not they are internet users. A deeper analysis of this online participatory class (see Part Four, “Will Social Media Change Everything?”) suggests that it is not inevitable that those with high levels of income and education are the most active in civic and political affairs. In contrast to traditional acts of political participation—whether undertaken online or offline—forms of engagement that use blogs or online social network sites are not characterized by such a strong association with socio-economic stratification.

In part, this circumstance results from the very high levels of online engagement by young adults. Some 37% of internet users aged 18-29 use blogs or social networking sites as a venue for political or civic involvement, compared to 17% of online 30-49 year olds, 12% of 50-64 year olds and 10% of internet users over 65. It is difficult to measure socio-economic status for the youngest adults, those under 25 — many of whom are still students. This group is, in fact, the least affluent and well educated age group in the survey. When we look at age groups separately, we find by and large that the association between income and education and online engagement re-emerges—although this association is somewhat less pronounced than for other forms of online political activism.

The impact of these new tools on the future of online political involvement depends in large part upon what happens as this younger cohort of “digital natives” gets older. Are we witnessing a generational change or a life-cycle phenomenon that will change as these younger users age? Will the civic divide close, or will rapidly evolving technologies continue to leave behind those with lower levels of education and income?

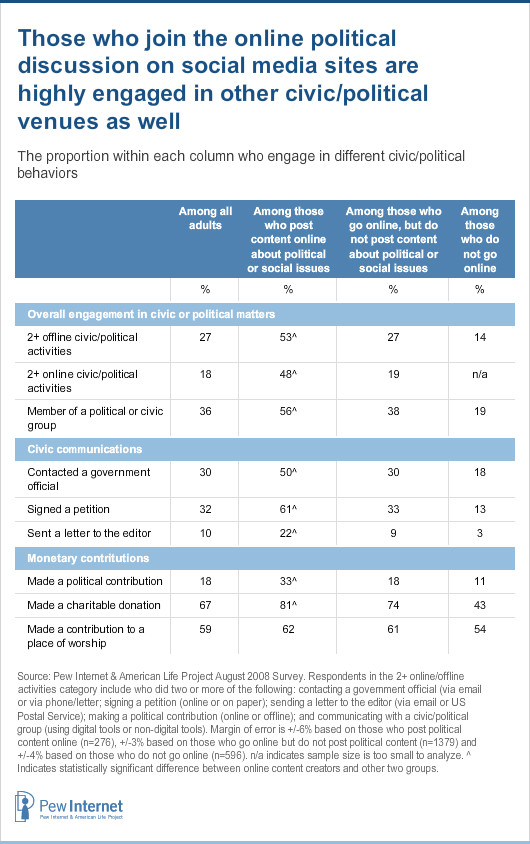

Those who use blogs and social networking sites as an outlet for civic engagement are far more active in traditional realms of political and nonpolitical participation than are other internet users. In addition, they are even more active than those who do not use the internet at all.

Those who use blogs or social networking sites politically are much more likely to be invested in other forms of civic and political activism. Compared to those who go online but do not post political or social content or to those who do not go online in the first place, members of this group are much more likely to take part in other civic activities such as joining a political or civic group, contacting a government official or expressing themselves in the media. Only when it comes to making a contribution to a place of worship are the differences among these groups quite minimal.

The internet is now part of the fabric of everyday civic life. Half of those who are involved in a political or community group communicate with other group members using digital tools such as email or group websites.

Just over one-third of Americans (36%) are involved in a civic or political group, and more than half of these (56%) use digital tools to communicate with other group members. Indeed, 5% of group members communicate with their fellow members using digital technologies only. At the forefront is email—fully 57% of wired civic group members use email to communicate with fellow group members. This makes email nearly as popular as face-to-face meetings and telephone conversations for intra-group communication. In addition:

- 32% of internet users who are involved in a political or community group have communicated with the group using the group’s website, and 10% have done so via instant messaging.

- 24% of online social network site users who are involved in a political or community group have communicated with the group using a social networking site.

- 17% of cell phone owners who are involved in a political or community group have communicated with the group via text messaging on a cell phone or PDA.

Respondents report that public officials are no less responsive to email than to snail mail. Online communications to government officials are just as likely to draw a response as contacts in person, over the phone, or by letter.

Individuals who email a government official are just as likely to get a response to their query—and, more importantly, to be satisfied with the response they receive—as are those who get in touch with their elected officials in person, by phone, or by letter.

Among those who contacted a government official in person, by phone or by letter, 67% received a response to their query. This is little different from the 64% of those who received a response after sending a government official an email. Similarly, 66% of individuals who contacted a government official by phone, letter or in person were satisfied with the response they received, which is again little different from the 63% who were satisfied with the response to their email communication.

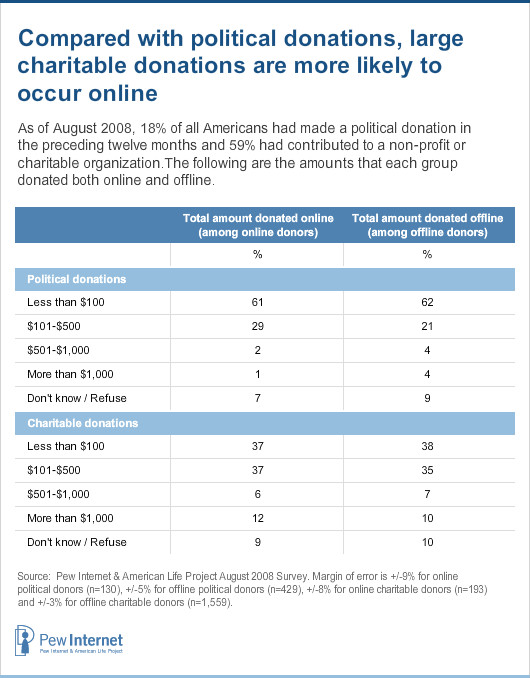

Those who make political donations are more likely to use the internet to make their contributions than are those who make charitable donations; however, large political donations are much less likely to be made online than are large charitable donations.

Compared to political donations—that is, contributions to a political candidate or party or any other political organization or cause—donations to non-profit and charitable organizations are far more likely to take place offline. Some 30% of political donors gave money online, compared to just 12% of charitable donors. Interestingly though, charitable donors seem more willing than political donors to make large contributions over the internet. Offline political donors were nearly three times as likely as online donors to make a contribution of more than $500 to a political candidate or party: 8% of those who made political donations offline contributed more than $500, compared with just 3% of online donors who gave a similar amount. In contrast, online and offline charitable donors were equally likely to make such large contributions.

A special note about this survey

The findings reported here come from a survey that was conducted in the midst of one of the most energizing political contests in modern American history, in which an African-American headed a major-party ticket for the first time. His campaign made a particular effort to incorporate the internet into his campaign. In addition, the U.S. economy was under enormous stress. Thus, there is the possibility that the patterns described here might not hold in the future.

In addition, this was the final survey conducted by the Pew Internet Project not to include a random sample of respondents contacted on their cell phones. Young adults and minorities are more likely not to have landlines and exclusively use cell phones. A sampling on cell phones would likely have produced more young respondents and more minority respondents. The data here were weighted to reflect the composition of the entire U.S. population and there is evidence in other Pew Research Center surveys that the absence of a cell sample would not substantially change the final results.

Comprehensive work on this has been done by our colleagues at the Pew Research Center for The People & The Press and is available here: http://pewresearch.org/pubs/1266/polling-challenges-election-08-success-in-dealing-with.