The Changing American Family

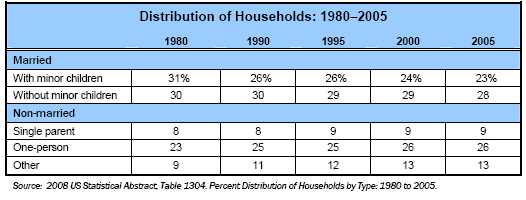

Historically known as a cohesive unit (Burgess, Locke & Thomas 1971),2 the American family has changed in recent decades. In the past two generations there has been a steady decline in the number of married-couple households with children – the family configuration traditionally called the “nuclear family” that has been the Fun with Dick and Jane norm of American life. Between 1980 and 2005, the overall proportion of such households fell from 31% to 23% of all families in the United States, and this decrease has been accompanied by a rise in the number of single-person households (from 23% in 1980 to 26% in 2005) and in the number of households classified as “Other” by the U.S. Census Bureau. The “Other” households include those where siblings or other relatives live and those made up of non-related roommates.

These changes have been accompanied by substantial shifts in the resources available to families and striking alterations in parental roles inside the home. Much of the change is driven by the rise of women in American workplaces. In 1960, 38% of women were employed outside the home. That figure leapt to 59% in 2006 and compared with years past, both men and women now spend notably different amounts of time on childcare, housework and other activities.

Between 1965 and 2005, the amount of time mothers spend every day on housework (including cooking, cleaning, outdoor chores and repairs, and household paperwork) has decreased from an average of 4.6 hours to an average of 2.7 hours, while the amount of time spent by men rose from an average of 0.6 hours to 1.7 hours.

Similarly, while mothers continue to spend more time than fathers caring for children, men have more than doubled the amount of time they spend caring for their children (Sayer 2005).

These changes have altered family life and added stresses to it.

Numerous studies have highlighted the demands of employment on household life. Dual-income households grew from 39% of all households to 53% between 1970 and 2007 (Blau et al 2005; U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics). As a result, wives and husbands must negotiate multiple work and school schedules in addition to domestic work (such as cooking, cleaning and maintenance), child care, family time, and social and leisure activities.

People are spending more hours per week on paid work than ever before (Robinson & Godbey 1997): the average number of hours husbands and wives combined spent on paid work increased from 52.5 hours per week in 1970 to 62.8 hours per week in 1997 (Jacobs & Gerson 2001). This often leaves families pressed for time and requires them to continually multitask throughout the day. Some have shown how this also leaves spouses with less time for each other and/or their children (Turcotte 2007; Milkie et al 2004; Mattingly & Sayer 2006). For instance, political scientist Robert Putnam (2000) documented that families have dinner together less often than they did thirty years earlier. Others have suggested that families have coped with these time pressures by watching less TV (Moscovitch 1998; Turcotte 2007), cutting back on their volunteer work (Putnam 2000; Rotolo 1999), or socializing less with neighbors and friends (McPherson et al 2006; Paxton 1999; Wang & Wellman 2008). All of these trends have implications for how satisfied people are with the amount of time they have to spend with family, friends and on leisure activities.

What role does technology play in family life?

Now the question arises: How do new communication technologies — the internet and cell phones in particular — fit into this picture? Some have argued that internet use in the home is an asocial activity (Nie & Hillygus 2002). Others have pushed back, arguing that the internet sustains social activities (Wellman & Haythornthwaite 2002).

This report is designed to provide a fuller picture of the role of information and communication technologies in everyday household life to address basic questions that have not received systematic attention:

- How do spouses and partners use the internet and their cell phones with each other?

- How do they employ these tools with their tech-using children? (To address this question, we focus on families with children ages 7-17 on the assumption that few children under age 7 have cell phones or use the internet.)

- How do they fit the role of these new technologies in the larger context of overall family communication?

- Do these new technologies encourage household members to act more as individual agents rather than as members of a solidary unit? In other words, when people have their own cell phones and computers, do they remove themselves from, transform or enhance family activities?

- How do parents feel these technologies affect family communication, specifically the quality and amount of time household members spend together?

These questions were probed in a nationally-representative phone survey of 2,252 adults between December 13, 2007 and January 13, 2008. There are many different kinds of households and family arrangements in America, and we decided to concentrate our research on two kinds of households:

First, we focused on married couples and those living with a partner in a relationship similar to marriage.3 There were 1,267 respondents in this sample who fit that description. Our purpose in doing so was to focus on households around which there is some of the most intense and policy-related interest. Scholars and other analysts have pondered for decades whether new technologies are rearranging traditional family relations, encouraging new roles for family members, and changing communications patterns inside families. Therefore, one key interest for us was on the communication patterns and relations of those inside married households.

Second, we paid particular analytical attention to families with minor children because there is continued ferment among policy makers in assessing the ways in which technology is changing how children engage with the world and interact with those around them. In this category, there are two subgroups that most interested us. The first subgroup was households where married/living as married couples had children. This sample contained 482 respondents who live in such households.

The second subgroup was households where minor children lived with a single parent. There were 83 respondents in that group. Unfortunately, that is not a big-enough subpopulation to do much meaningful statistical analysis.

These choices necessarily limited the scope of this research, as we did not interview in depth those who live in group households, those who live in homes where the main occupants are not in romantic or formal relationships, and we did not ask about the communication patterns of extended families, such as families with adult children, or families where members live outside a single household.

Although there are fascinating and important questions about how the internet and cell phones might be affecting relations in those types of family and household situations, investigating them in this study would have taken this work in more directions than we could possibly have been able to address.