Introduction

The experience of game play can be affected by many things—what hardware or software is used to play the game, what kind of game is being played, whether one is playing with others, and what types of experiences one has while playing the game. This section addresses the latter two elements—the situational and experiential aspect of game play—and explores the social nature of gaming as well as the pro-social and anti-social experiences that gaming with others offers.

Social game play is thought to offer the possibility for youth to have collaborative and interactive experiences, experiences that potentially parallel many real world political and civic activities. Some scholars47 have suggested that play in groups with others, particularly when working collaboratively toward a common goal (as with guilds and game groups in MMOGs), lays the groundwork for learning how to work with groups toward a common goal in other facets of life, particularly within the workplace and community. In this way gaming provides civic learning experiences—something we discuss in Part 2.

The flip side is the potential in gaming for gamers to observe anti-social behavior. This section explores the prevalence of these kinds of observations, as well as whether others playing the game responded to those anti-social, in-game moments.

Games are social experiences for the majority of teens, but teens also play games alone.

Teens play games with other people—sometimes with people in the same physical location, other times with friends or others online. Even when they are not playing games with others, teens talk and engage with others about games—by posting comments on discussion boards and websites or by writing reviews and “walk-throughs” that assist newcomers to a particular game by showing them how to play the game.

Many teens play games with others.

Overall, 76% of teen gamers play games with other people in some way, either online or in person. Nearly two-thirds (65%) of teens say they play games with other people who are in the same room with them. Teens from households with lower levels of education are more likely than teens from households with higher education levels to play games with others in the room at the same time. There are no gender, age, or racial differences among those who plays games together with people in the same room.

More than one-quarter (27%) of teens who play games do so with others who are connected to them through the internet. Boys are more likely to play games with others on the internet than girls, with more than one-third of boys (34%) reporting internet-connected group game play, compared with 19% of girls. Teens with broadband access (31%) are more likely to play games connected to others through the internet than dial-up users (15%). There is no statistically significant difference by age. Playing with others via the internet is the least popular way for teens with broadband to play games with others—31% of broadband users play with others online, while 62% of teen broadband users play with others in the same room.

Teens also play games alone.

While gaming teens enjoy the social aspect of playing games with others, solo play remains very popular, as 82% of teens play games alone. Hispanic teens are more likely to report solo game play than white (though not black) teens (92% vs. 81%). Likewise, teens from households with low levels of parental education are more likely to play games alone than teens from households with higher levels of education (86% vs. 78%). Boys and girls and younger and older teens are all equally as likely to report playing games by themselves. However, few teens report that solo play is their sole method of gaming—24% of game-playing teens say they only play by themselves.

More than half of teens most often play with other people.

More than half (59%) of teen gamers play games in more than one way, switching between playing with others and playing alone. Of teens who play games in more than one way (with others online, in person, or alone), equal numbers say they play most often with others in the same room and by themselves, with 42% of teens in each group. About 15% of teens who play games in multiple ways say they play most often with others to whom they are connected virtually, meaning that 57% of teens who play in more than one way most often play with other people either virtually or in person. Among teens who play games in multiple ways, gamers with home broadband connections are more likely than dial-up users to report playing with others online, with 19% of broadband users playing online with others, compared to 6% of dial-up users. Otherwise, there is little other variation among modes of game play, including by race or socioeconomic status.

A significant number of online gamers play games in groups.

Among teens who play games with others online, more than two in five (43%) say they play games online as a part of group or guild; 54% of online gamers do not play as a part of a group. White teens who play games online with others are more likely than Hispanic teens (but not blacks) to play as a part of a guild or group; 46% of white teens play online in guilds, while 22% of Hispanic teens who play games online with others report playing in groups. Forty-four percent of black teens who play online with others report playing as a part of a guild or group.

Most teens play online games with friends they know in their offline lives.

We asked teens who play online games with others how they knew the people they play games with online. Close to half of teens (47%) say they play games online with people they know from their community or with distant friends and family. More than one-quarter (27%) of teens say they only play online games with people they first met online, and another quarter of teens (23%) play with family and friends from their offline lives as well as with people they met online. Girls are more likely than boys to say they play games with people they know from offline relationships, with 58% of game-playing girls reporting such behavior, compared with 41% of gaming boys. Boys are more likely to report playing games both with people they know from their offline lives and people they first met online: 29% of gaming boys play with both types of people, compared with just 14% of girls.

Younger teens are also more likely to report game play with offline friends. More than half (52%) of teens ages 12-14 play online games with in-person friends, compared with 42% of teens ages 15-17. Older teens are more likely to report playing games with people they first met online—one-third of teen gamers ages 15-17 play with people they met first online, compared with 22% of younger gamers ages 12-14. White teens are more likely than black (but not Hispanic) teens to say they play games both with people the first met online and friends from their physical life (29% v. 11%).

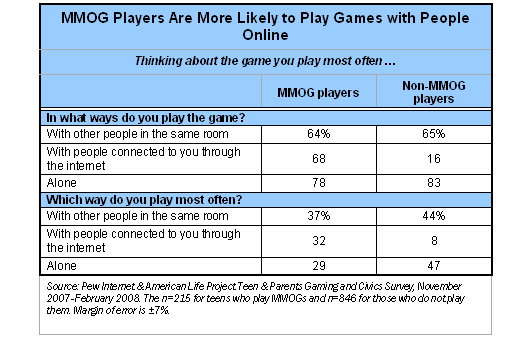

MMOG players are much more likely to play games with others online.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, given the group game-play mechanics built into MMOGs and the complexity of their quests, MMOG gamers are more likely than those who do not play these games to play games with people who are connected to them through the internet: 68% of MMOG players report this type of play, compared with just 16% of non-MMOG players. MMOG players are also much more likely to say that playing with others to whom they are connected via the internet is the way they play most often, with nearly one-third (32%) of MMOG players reporting this as their predominant mode of game play, compared with 8% of those who do not play MMOGs. However, even with the popularity of internet-connected game play among MMOG gamers, the largest section of this group (37%) plays games most often with others in the same room.

More than one in three teens has played a video game for school.

One-third (34%) of American teens have played a computer or console game at school as part of a school assignment. Lower-income teens (41%) and teens from homes with lower overall education levels (41%) are more likely than their counterparts (29%) to have played a game for school. Black teens (46%) are more likely that white teens (32%) to have played a game at school for educational purposes. Younger teens are also more likely to have played a game at school than older teens: 40% of teens ages 12-14 have played a game at school as part of a school assignment, while 29% of teens ages 15-17 have done so.

When asked what games they played in school, many teens said they could not quite remember or that they played “math games” or “typing games.” Thus, we are not able to report on the most commonly played games with a degree of precision, and it was clear that no one game or one kind of game predominated. The games mentioned by five or more teens were: Oregon Trail, Fun Brain, Lemonade Stand, and Roller Coaster Tycoon.

Pro-social and anti-social behavior in games

The social critique of video games has a long history, ranging from concerns about the health effects of spending long hours in front of a screen to diminished attention spans among those who play them. One significant critique has to do with the potential games have for teaching young people anti-social behaviors and attitudes. While this survey did not attempt to comprehensively address this issue, below are the results of questions that asked about gamers’ observations of pro-social and anti-social behaviors in the context of game play.

The most popular game genres include games with both violent and nonviolent content. However, game genres that can include very violent content were played by the majority of teens. The two most widely played game genres were racing and puzzle games, played by nearly three-quarters of teens in the sample. These genres are noteworthy because they have little to no violent content. However, two-thirds of teens reported playing “action” or “adventure” games, some of which contain considerable levels of violence.48

Both violent and nonviolent games were among the most popular franchises reported in teens’ top three games.

As described in Part 1, Section 2, we asked teens to name the top three games they currently play. The top five game franchises teens mention in this survey are: Guitar Hero, Halo, Madden NFL, The Sims, and Grand Theft Auto. While Guitar Hero, the most often mentioned franchise in teens’ top games, contains nonviolent content, Halo, at number two on the list, has an M, or mature, rating for “blood and gore.” Grand Theft Auto, also rated M for “intense violence, blood, strong language, strong sexual content, partial nudity, and use of drugs and alcohol” is number five. Madden NFL and The Sims contain little to no violence.

Despite efforts to limit teens’ access to ultra-violent or sexually explicit games, many teens report playing mature- and adult-only-rated games.

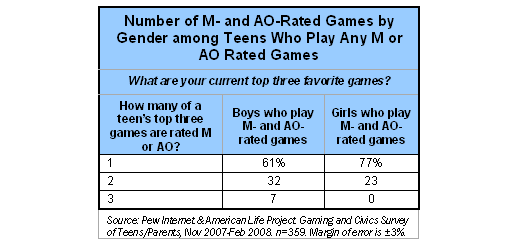

Almost one-third (32%) of all the teens in our survey play at least one game rated M or AO. Of these M- and AO-rated game players, 79% are boys and 21% are girls. Furthermore, 12- to 14-year-olds are equally likely to play M- or AO-rated games as their 15- to 17-year-old counterparts. Nearly three in ten (28%) of 12- to 14-year-olds list an M- or AO-rated game as a favorite, as do 36% of teens ages 15-17.49

For a small number of teens, all three of the games mentioned have a version with an M or an AO rating; for others, only one or two of the games they offered as their top three current favorites was an M- or AO-rated game.

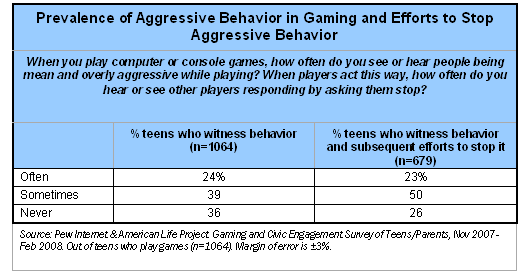

The majority of teens who play games encounter aggressive behavior while playing games, and most of those teens witness others stepping in to stop the behavior.

Among teens who play games, 63% report seeing or hearing “people being mean and overly aggressive while playing,” with 24% reporting this happens “often.” Of those who have had these experiences, 73% state they have seen or heard other players ask the aggressor to stop, with 23% reporting that this happens “often.”

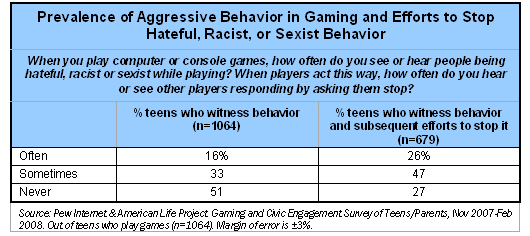

Among teens who play games in our survey sample, 49% report seeing or hearing “people being hateful, racist or sexist while playing” at least sometimes, and 16% report this happens “often.” Among teens who witnessed these behaviors, 73% state they have seen or heard other players ask the aggressor to stop at least sometimes, and 26% have witnessed this “often.”

Boys are more likely to report witnessing negative behavior than girls but are no more likely to witness others stepping in to stop the behavior.

Among teen gamers, nearly three-quarters of boys report seeing mean or overly aggressive behavior, compared with just over half of girls. Boys are also more likely to witness hateful, racist, or sexist behavior, with 57% saying they have had this experience, compared with 39% of girls.

Teens who play games also witness a large amount of “pro-social” behaviors. These are behaviors that encompass activities that society generally values, like positive social interaction skills, self-regulation, and achievement behaviors and creative play.50

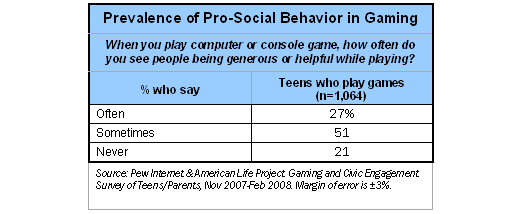

More than three-fourths of teens who took the survey report witnessing “people being generous or helpful while playing,” and 27% reported seeing this happen “often.”

For many, it is more than game play—36% of gamers read game-related reviews, websites, and discussions.

Beyond playing a game on a console, computer, or mobile device, many teens also engage with content and with other players on websites and in discussion spaces about games generally or a particular game more specifically. More than a third of gamers (36%) read websites, reviews, or discussions related to games they play. Another 12% of gaming teens contribute to these sites, write reviews, and participate in discussions about games they play.

Boys and younger teens are more likely read game-related websites and discussions.

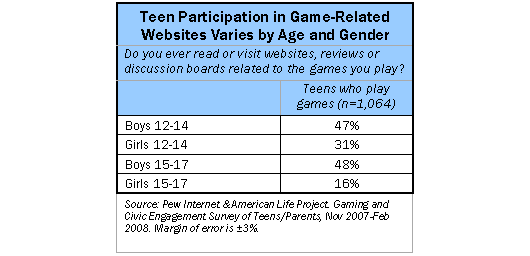

Nearly half of boys gamers (47%) visit such sites and read reviews and chats about games they play, compared with less than a quarter (23%) of girls who game. Those ages 12-14 are also somewhat more likely than older teens to read these websites; 39% of 12- to 14-year-olds read them, as do 32% of 15- to 17-year-olds. When looking at age and gender together, the older girls (ages 15-17) are much less likely than any other group to engage with game-related websites or online discussions—just 16% of girls ages 15-17 visit these sites, compared with 47% of all boys and 31% of younger girls.

Playing games with others online, playing MMOGs and virtual worlds all increase the likelihood that a gamer will visit game-related websites.

Not surprisingly, active online gamers are the most likely to use the web to visit game-related websites. More than half (56%) of teens who most often play games online with others read game-related websites and discussions, while 31% of those who play most often with others in the same room and 35% of those who most often play alone say they visit these sites. Similarly, 59% of MMOG players read websites, reviews, and discussions about games they play, while 29% of teens who do not play MMOGs visit them. More than half (54%) of teens who visit virtual worlds read websites, reviews, and chats about they games they play, compared with a third (33%) of teens who do not use virtual worlds.

More than one in ten teens contribute to game-related websites.

A bit more than one in ten teens (12%) contribute to websites, reviews, and discussions about games they play, and boys are more likely than girls to contribute to these websites or online discussions. About one in six boys (14%) contribute to game-related websites and chats, while 9% of gaming girls do the same. Unlike the pattern among those who read material at these sites, there is no age differential in contributing to game-related websites or discussions.

About a quarter (24%) of teens who play games more often with others online contribute these sites, compared with 9% of teens who play games with others in the same room and 11% of teens who most often play games alone. MMOG players and virtual world users display similar behaviors; 26% of each group contributes to websites, reviews, or discussions around games they play, compared with 8% of those who do no play MMOGs and 10% of those who do not use virtual worlds.

More than one-third of teen gamers use cheat codes or game hacks.

When teens visit game related websites, they sometimes search for codes that allow them to access hidden game content and new, modified versions of games that have been built or altered, often by other players. Cheats or game hacks are codes generally created by the game designer that allow the player to access more content in a game. More than a third (37%) of teens who play video games use cheats or game hacks. Boys are much more likely to use these codes than girls, with half (50%) of all boy gamers using cheat codes “often” or “sometimes” —more than double the 23% of girls who use the codes. Teens of all ages use cheats at about the same rate.

Cheats or game hacks are codes or button combinations, generally created by the game designer, that allow the player to access more content or alter game play.

Teens who have a game console (though this is not necessarily the only way they play games) are much more likely than teens who do not have a console to use game cheats to unlock hidden content—41% of console owners use the codes, compared with just 9% of teens without consoles. Daily game players are also more likely to use cheats and game hacks than teens who play less often, with nearly 45% of daily gamers using cheats, and 34% of those who play less often employing the codes.

Close to three in ten gaming teens have used “mods” to alter the games they play.

Mods are pieces of player-created computer code that change something in the game. Modding (or building mods) generally requires the use of a computer to alter the source code of a game, whether that game is played on a computer, console, or other device. Mods can take various forms. Some may create new parts of a game, such as making new characters, weapons, and locations. Some mods completely change a game so that it bears little resemblance to the original game. More than a quarter (28%) of teens who game have used mods “often” or “sometimes” to change the games they play.

“Mods” are pieces of third-party-created code that change something in the game. Modding (or building mods) generally requires the use of a computer to alter the source code of a game.

Boys are more likely to use mods than girls, though the differences are less stark than the differences between the sexes in the use of cheat codes. More than a third of boys 36% use mods, while one in five girls (20%) employ them to change the games they play. Teens who play games daily are also more likely to use mods than their less-frequent gaming counterparts; 37% of daily games use mods and 24% of less-frequent gamers do.

Teens who play games online in guilds or groups are more likely to employ mods to change the games they play: 44% of players in guilds using mods, while 27% of teens who don’t play in online guilds or groups use them.

Teens who use game cheats and mods are more likely to visit game-related websites.

The internet offers a wealth of information about cheat codes, hacks, and mods. Often, mods and cheat codes are acquired at websites or in online forums about games. Gamers who utilize these game-changing tools are much more likely than other gamers to read or visit websites, reviews, and discussion boards devoted to the games they play. Roughly half of gamers who use cheat codes or hacks (51%) read reviews or visit websites and discussion boards devoted to their favorite games, compared with 27% of gamers who do not use cheats or hacks. Similarly, 51% of gamers who use mods or other user-generated code go online or read reviews of games, compared with 30% of those who do not use mods.

Interestingly, while gamers who use cheat codes are more likely to read about their favorite games, they are not more likely to actually contribute to websites or discussion boards about their favorite games—14% of those who use cheat codes do this, compared with 10% of those who do not use cheat codes, which is within the margin of error for this survey. In contrast, gamers who use mods or other user-generated code to make changes to the games they play are, in fact, more likely than other gamers to contribute to gaming websites and discussion boards. Roughly one in five gamers who use mods (19%) contribute to these sites, compared with one in ten (9%) of those who do not use mods or other user-generated code.