Comparing email to other kinds of communications

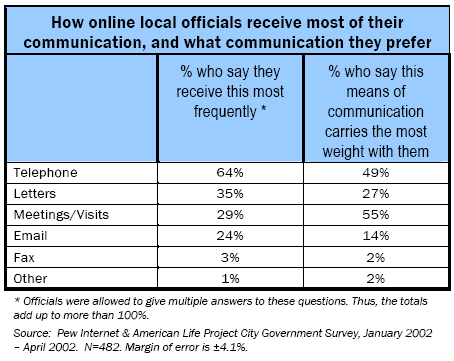

We asked officials to tell us how citizens contact them, and what kinds of contact carry the most weight with those who are elected city leaders. Consistent with our anecdotal findings that Americans do not rely heavily on the Internet for local purposes, online officials say citizens are more likely to pick up the phone, write a letter, or pay a visit than to sit down to compose an email. And officials seem to be happy with this. Despite the accommodations they make to receive constituent email at work and at home, most responded that phone calls, letters, and visits carried more weight with them than did email. Email is preferred only to fax, which is preferred by virtually no one (2%).

Nonetheless, many officials opted out of ranking any means of communication as more worthy than any others, stating that they welcomed all communications equally (though one such official specifically excepted form letters). Another official welcomed any communiqué “as long as the person identifies himself.”

Is email a burden to officials?

Unlike their counterparts in Congress, online local officials have not been generally bothered by the volume of email they receive. Fully 75% of online local officials say they are capable of handling it, even though many do not have staffs or formal offices. Only one in eight (12%) indicated that email volume poses some problems. This satisfaction is consistent regardless of how frequently officials use email, how many people they represent, and how many of their constituents have Internet access. Online officials agreed on this point more than they did any other question evaluating the effects of email.

One factor that may contribute to this finding is the relatively small amount of non-constituent email. Congress members vote on issues with national ramifications. They may receive email from activists nationwide, while being directly accountable to only the voters of their own districts. The Congress Online Project reported in 2001 that most Congressional email comes from non-constituents, and that staffers spend a significant amount of time weeding out and discarding those messages.8 It is likely that city officials are far less likely than members of Congress to be plagued with non-constituent email, although we did not directly ask local officials if their email came exclusively from the voters who elected them.

Email contributes to understanding of community opinion

Seventy-three percent of online officials in our sample agree that the exchange of email with citizens contributes to their understanding of community opinion. About one fifth of online officials in our sample (21%) say that mass email campaigns demonstrated a unity and sense of purpose of which they had been previously unaware. The benefits appear to increase in more connected cities. Some 84% of online officials who live in highly wired communities (those where over half the population has access) say email helps their understanding of community opinion. Moreover, the officials who use email most often are the most likely to extol its virtues. Some 92% of the officials who use email with citizens daily say email helps them discern local sentiment.

Conversely, officials from cities reporting the lowest levels of access are less likely to benefit in this manner. About 64% of online officials from low-access cities (communities with under 30% of the population online) agreed with this statement: “Due to low levels of Internet access in my city, I cannot rely on email to help me get a true sense of community opinion.”

Officials say email is a moderately effective tool for promoting policies

Email presents some benefits and few pitfalls to officials in managing their community relations. Some 56% agree that email has helped their relations with community groups – 11% agree strongly. Understandably, officials are more likely to find email useful in their community relations as the number of residents with email access increases. About 47% of those in low-access cities agree that it is useful, compared to 71% of those in high-access municipalities.

Most of these officials say email and the Internet have not generated new and difficult-to-meet expectations about how local officials do their jobs. While letter writers may expect several days to elapse before getting a response, it has been suggested that email writers expect acknowledgements of their missives right away. When asked if email encouraged unrealistic expectations for responsiveness, 54% of said no. That still leaves a significant minority – 30% – for whom email has created some problems (16% of respondents provided no opinion). There were no clear patterns to help explain why some officials had no problems with citizen expectations and others did. The differences were not explained by the position the officials held (mayors compared to city council members), their frequency of email use, the percent of constituents with Internet access, or city size.

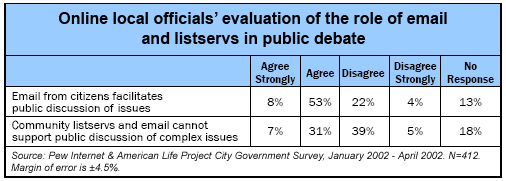

Mixed reviews on how well email supports public debate on knotty local issues

We asked officials to indicate the extent to which they agreed with two statements: “Email from citizens facilitates public discussion of complex issues” and “Community listservs and email cannot support public discussion of complex issues.” The results indicate that the role of electronic communications in complicated policy disputes is not clear-cut.

Some 61% of officials agree that email can facilitate discussion of complex issues. Further, we find correlations that show officials from larger cities, officials in cities with higher levels of Internet access, and officials who use email frequently are more likely to agree.

At the same time, however, a large minority (38%) also agreed with the statement “Community listservs and email cannot support public discussion of complex issues.” This includes 35% of the officials who agree that the email can facilitate public debate. Furthermore, when asked to rate email’s effectiveness for accomplishing a variety of goals, officials gave “engaging the public in debate” an average score of “Not very effective.”

It appears that officials believe that the use of email should not be judged to be good or bad communications tool on it own. Rather, the message seems to be that the usefulness of email is limited. On the one hand, email and community listservs certainly provide an easy medium for participating in local debates. Anyone with an email account can participate, at any time that is convenient. Conscientious participants can ensure they provide compelling responses by taking time to research press and government sites, which they can link to their posts. One respondent to our Web site request for anecdotes credited email with helping citizens overcome media monopoly in getting public opinion delivered to city government. However, nothing in listserv technology itself drives consensus building, or even clarification of divided opinion, both of which are crucial to public discussions. These factors may contribute to the mixed review that email receives when officials judge how useful it is in gauging and guiding public opinion.

Mixed reviews on email as a tool for outreach

About half (48%) of the online officials in our sample agreed that email has enabled them to reach out to neighborhood or issue-oriented groups. The most frequent users of email are more likely than non-frequent users to have used email this way. Some 74% of those who use email daily for official purposes say they have done outreach to local groups and these heavy email users are also more likely than other officials to have from local groups via email. One official notes sending out periodic informational emails to constituents. A mayor from a city of 21,000 wrote enthusiastically about how the city’s mass email campaigns have effectively mobilized citizens, including getting 600 to show up for a “locally important Federal hearing.”

Another official tempered the email effect by noting that it “expedited” rather than “enabled” outreach to citizens.

At the far end of the spectrum are about 50 online officials who declined to address any of the evaluation questions, many saying that they simply did not have enough experience dealing with citizens through email to assess email’s value. One wrote emphatically in all capital letters: “DO NOT LIKE TO USE EMAIL TO COMMUNICATE WITH RESIDENTS!”

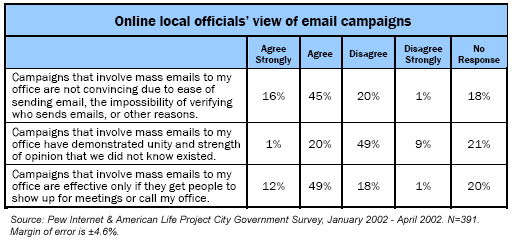

Online local officials are not overly impressed by mass email campaigns, but note that some do bring local concerns to light

Some activists have taken up the strategy of trying to influence officials by urging citizens to email their elected officials. The activists sometimes will provide the text of the email so that individuals can simply cut, paste, and send it to the local leader. The effectiveness of this kind of campaign has been questioned in some quarters. While there have been some leaders who were caught off guard by the scope of feeling in the community communicated via full email in-boxes, others find such campaigns frustrating and as easy to ignore as activists found them easy to generate. One tactic some activists take to try to increase the urgency and potency of communications has been to encourage citizens to follow an email with a fax on the same issue. Their reasoning is that an inbox physically overflowing with a stack of paper faxes is more compelling than an email box full of electronic messages. Our survey suggests this is not a very persuasive technique. Only 2% of officials say that they give weight to faxed correspondence.

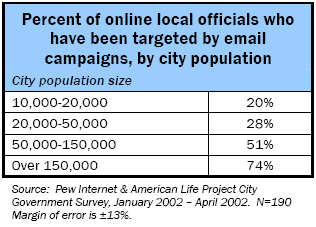

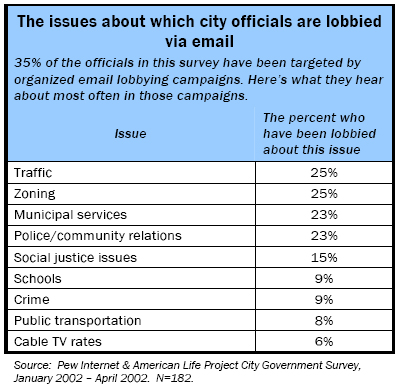

Just over one third (35%) of online local officials report having been targeted by a mass email campaign. Some 12% report being targeted by a fax campaign. Officials in larger cities were the most likely to have received organized email. The most frequent issues addressed in these campaigns include traffic, zoning and municipal services. We asked officials to write in any specific campaign issues that were not included in the survey responses. These included a variety of environmental concerns, parks and recreation issues, salaries for municipal employees, queries about online local officials’ views on national and international issues, and development issues, as well as a few eye-poppers such as “having a pig for a pet” and “animal alteration (don’t ask).”

These campaigns have achieved mixed results. Half of targeted officials said such campaigns had persuaded them “in part” of the merits of a group’s arguments, but that may mean little to the citizens concerned. “One can appreciate the merits of an argument and still vote the other way,” noted one official. Almost half (48%) said such campaigns had not had any persuasive power whatsoever. Only 1% of online officials said they were targeted by campaigns so stellar that they were convincing.

Sixty-one percent of online officials agree that “Campaigns that involve mass emails to my office are not convincing due to the ease of sending email, the impossibility of verifying who sends emails, or other reasons.” One in six (16%) agree strongly. The sentiment holds both in theory and in experience – even officials who had never been on the receiving end of an organized email campaign said such campaigns would carry little weight with them.

Even email enthusiasts among our respondents generally prefer not to be on the receiving end of mass email campaigns. Among those who use email daily in their communications with citizens, 60% still express tepid feelings for this form of activism. Also, 61% of those who attribute significant weight to email communications also dislike mass email campaigns.

On the other hand, if such campaigns are not popular, neither are they universally reviled. Some 25% of online officials claim that online campaigns directed at their offices “showed good background research, plausible solutions, and demonstrated public support,” although not all of them said they had been targeted by such a campaign. Among those who have, the agreement level increases to 42%. On the other hand, 36% of targeted officials agree that online campaigns directed at their office have been “poorly organized and irritating.” One particularly frustrated respondent noted that such campaigns appear to come from a “[h]andful of malcontents. Same people, same message, just more garbage to sort through.”

Of course, we cannot contend that these campaigns would have been more successful if organizers had asked their supporters to use the phone rather than their modems, even if officials do claim to give more weight to phone calls. Political campaigns require more strategic thinking than that. Some officials may truly prefer email and be more open to it. Some may be unavailable by phone. Some may have definite preferences that need to be taken into account. One official said “For the foreseeable future I don’t see email changing my mind on issues. I need personal contact to understand issues [on which] I differ [with constituents].”

Apparently, email campaigns can work within the context of a larger communications effort. Sixty-one percent of online officials agreed that such campaigns are successful “only if they get people to show up for meetings or call my office.” Given the overall preference for meetings and phone calls as means to communicate with citizens, this is not surprising.