Are Internet users singing out for that online religion?

As early as 1996, “Time” magazine documented a rich world of online religion sites.1 It started with the Monastery of Christ in the Desert in remote New Mexico. The depiction of that natural beauty and peace that pervades the monastic landscape was expected. The image of robed monks mastering HTML code and jerry rigging an Internet connection through solar panels and a single cell-phone line was not. It illustrated a new world of spiritual place, time, and practice.

This site (http://www.christdesert.org/pax.html) is only one example among thousands demonstrating how people of faiths both mainstream and esoteric can find something for themselves online. Whether they need advice on fine points of canonical law, special music for a service, ideas for devotional study, material for a religious class, support in prayer, or simply a spirited debate that they cannot introduce in their own circle of friends, they can find it all in the glow of an Internet-connected monitor. The Web allows the faithful wide access to resources and links, and it offers the doubtful or curious a safe place to explore. It is a favorite venue for those rejecting mainstream religions to revive ancient faiths. It allows for Luther-esque defiance of the reigning powers, as demonstrated by exiled Roman Catholic bishop Jacques Gaillot who has established an online “diocese without borders.”2 The richness of the landscape creates a lush spiritual plain that is explored here in a survey of how online Americans use religious and spiritual material online.

In a survey from August 13-September 10 this year, the Pew Internet & American Life Project found that about 28 million Americans, or 25% of the Internet population, visit religious cyberspace, with more than 3 million seeking spiritual material on any given day. This is an increase from a survey finding by the Project in late 2000, showing that 21% of a smaller overall population of Internet users had gone online to get religious or spiritual material. At that time about two million people were using such Internet material on any given day. We call these online Americans “Religion Surfers.”

Some may find comfort in the fact that spiritual browsing is a more popular online activity than online gambling, which has only been sampled by about 5% of the Internet population.3 The act of searching for spiritual material online has also been done by more Americans than have traded stocks or bonds or mutual funds online, or done online banking, or participated in online auctions, or used Internet-based dating services, or placed phone calls online.

The variety of sites available to them appears boundless. They range from denominations and branches with large constituencies to sites posted by individuals in veneration of their deities. They run the gamut from multi-faith, multi-service sites such as Beliefnet.com and FaithandValues.com to sites set up for specific faiths and purposes, such as introducing singles of the same religion.

The popularity of religious Web sites raises an important issue about the extent to which Religion Surfers view themselves as practicing religion online. Religious observance is by nature both solitary and communal, and the contribution of the Internet to that space can be confusing. On the one hand, the Internet could be seen as an electronic prayer book, an aid to personal devotion, or a reference guide to spiritual issues without being an actual part of religious observance. On the other hand, an Internet site could be a “place” where people come together, either to chat or to pray or even worship with people around the globe who may be at the same site at the same time.

Demographer George Barna believes that eventually the Internet will fundamentally change the nature of worship among Christians. In his surveys of both adults and teenagers he has found marked interest in online sources of religious inspiration, and believes that by the end of the decade, millions of individuals with no faith community will take to practice and worship on the Web. But he also warns that “millions of others will be people who drop out of the physical church in favor of the cyberchurch.”4

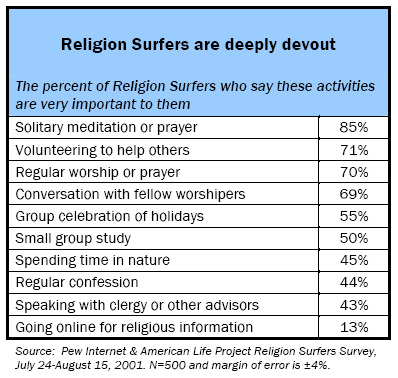

The Pew Internet & American Life Project turned to online Religion Surfers to explore Barna’s ideas, to get a sense of the things people do online when it comes to spiritual practices, and to learn how they think those activities affect their faith.

The audience is varied – most combine their online life with that of their own religious communities, seeking fuller comprehension and experience of their faiths. Some have long ago left their churches, synagogues, or temples, but still use the Internet to pursue their own spiritual needs. Some have changed faiths and seek out new information. Some feel isolated for their beliefs, and find communion with others in cyberspace where they cannot find it in their own neighborhoods. Many have mixed evaluations of the powers of the Internet. Many see it as a useful supplemental tool in their faith life, especially because it allows them access to additional spiritual information and resources. And they think that online spiritual material can be a force for good because it helps people of faith find each other more easily and because the availability of such material encourages religious tolerance. But they also worry that there is too much sacrilegious material online and that fringe groups can exploit Internet tools to damage others. The picture is as rich and varied as religious life itself.

This report is the first in a two-part study of religion and the Internet. This report is based on the results of a telephone survey of 500 adults who had told us in previous surveys that they sought out spiritual or religious Internet sites. It represents as closely as possible a random sample of all adult Internet surfers in the nation. The second part will be an online survey that will be open to all who care to participate, and in which we particularly hope to encourage the participation of religious minorities. For information on how to participate, write to info@pewresearch.org/internet.