I. Introduction

The Internet is not only one of the most rapidly disseminating technologies in history, it is also—to a degree different from other mass communications technologies—rapidly evolving as it disseminates. Today’s new adopters of the Internet face a range of options undreamed of by their predecessors of just a few years ago. With higher connection speeds, a greater variety of access devices, and a broader range of content, today’s Internet is different from the Internet of five years ago or even two years ago. Today’s Internet user is also different from the typical Web surfer of a few years ago. The early user of the Internet was likely to be a well-educated reasonably well-off white male. However, as the Pew Internet Project reported in May 2000, women now make up half of all Internet users, with older women in particular coming online at a slightly higher rate than other user groups.4 Hispanics are now about as likely to be online as whites, and African Americans are coming online at accelerating rates.

In general, people like the Internet and the number of years they have been online is strongly associated with the amount of time they spend online on a given day. Length of time online is also positively associated with the frequency with which they engage in Internet activities such as email, news gathering, game-playing, or online purchasing. However, not all Internet users are the same. Some people march up the Internet learning curve with astonishing speed and quickly fold it into their daily lives. Others find the technology less compelling and, even though they may remain online, are fairly unenthusiastic about the Internet.5

In this paper, I examine new users’ attitudes toward the Internet with particular focus on new users who are strongly enthusiastic about the Internet. Why new users and why new users who embrace the Internet enthusiastically? Enthusiastic new users, “Instant Acolytes” as I call them, are the sophisticated demanders of Internet services who are likely to shape the Internet’s future, in terms of the kinds of content that wins in the marketplace or the kinds of Internet access devices that become popular. Once, of course, “Instant Acolytes” were most of the Internet population, and these people—in the earliest days university researchers—gave the Internet its academic feel and established the “information wants to be free” ethic of the early Internet. With the advent of the Worldwide Web and the growing commercialization of the Internet, commerce has grown in prominence, but the growing Internet population has spurred a diversity of non-commercial content, from religious Websites to support groups that address people’s special concerns. As new “eyeballs” come to the Internet—eyeballs with different gender, educational background, and ethnic heritage—the most ardent users may have a disproportionate influence on how the Internet evolves in the future.

In addition to looking at the profile of recent Instant Acolytes, I will examine yesterday’s Instant Acolytes, who are today’s experienced users and the most wired among us. The comparison will provide a portrait of what enthusiastic new Internet users did online several years ago in contrast to what today’s Instant Acolytes do.

II. Definitions and Methodology

This paper is built on the findings of the Pew Internet and American Life Project’s tracking survey of Internet activities, which was designed to get an accurate reading on the impact of the Internet on Americans’ lives. Running almost continually since March 1, 2000, the daily poll has asked thousands of Internet users not only about what they have ever done online, but also about what they did “yesterday.” Using a daily sample design, this approach measures the scope of Internet activities more accurately than conventional surveys because it focuses on activities that are fresh in respondents’ minds. It also provides new insights into the range of online behavior that occurs daily. For March, the primary source of information for this report, the survey interviewed 3,533 Americans, some 1,690 of whom are Internet users. The section on privacy draws on the May-June Pew Internet Project poll, which interviewed 4,606 Americans and 2,277 Internet users.

Additionally, this paper uses data from a November 1998 Internet user survey conducted by the Pew Research Center for the People and the Press. Since 1995, the Pew Research Center has included questions about people’s Internet usage habits as part of its polling on how people follow the news. Many of the same questions from the Pew Research Center’s surveys have also been included in the Pew Internet and American Life Project’s surveys, which is an initiative of the Pew Research Center. The inclusion of the same questions permits the comparison between March 2000 and November 1998. The Pew Research Center poll interviewed 3,184 adults from October 26, 1998 to December 1, 1998. The Pew Research Center survey also included an over sample of 1,184 adult Internet users.

The Instant Acolyte classification is built on two questions from the surveys, one that asks “When did you first start going online?” and another that asks “How much would you miss the Internet if you could no longer go online?” For the Pew Research Center November 1998 survey 46% of users had gone online within the previous year, while 53% had been online for two years or more. In the Pew Internet Project March 2000 survey, 39% of Internet users reported going online within the previous six months, with 61% having been online for two or more years. With respect to missing the Internet, 72% of respondents in the March 2000 survey said they would miss that Internet “a lot” or “some” with 28% saying they would miss the Internet “not much” or “not at all.” In the November 1998 Pew Research Center survey, 68% said they would miss the Internet “a lot” or “some” while 31% said they not miss the Internet “not much” or “not at all.”

Instant Acolytes are a subset of Internet users who express an opinion on how much they would miss the Internet and also report how long they have been online. Specifically, Instant Acolytes are people who have not been online a long time, but who nonetheless say they would miss the Internet if they could no longer go online. As the following table shows, Instant Acolytes are one of four categories that come from combining the two questions.

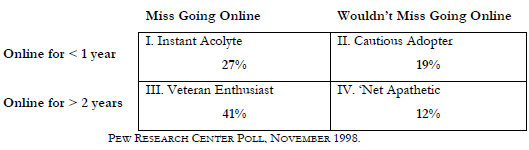

In terms of distribution of Internet users among the four categories, the breakdown for the November 1998 poll looks like this:

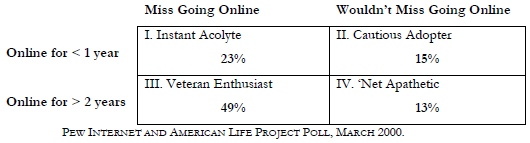

For the March 2000 Pew Internet Project poll, the breakdown is as follows:

There are some differences in the distribution of categories between 1998 and 2000, with 8 percent more users falling into the Veteran Enthusiast category in 2000, a slight drop in the share of Instant Acolytes, and a decrease in the percentage of Cautious Adopters. It is not surprising that the share of Veteran Enthusiasts has grown since 1998, because yesterday’s Veteran Enthusiasts are likely to stay that way and yesterday’s Instant Acolytes will swell the ranks of today’s Veteran Enthusiasts. The decrease in the share of Instant Acolytes likely has to do with the pool of new users the Internet draws from over time. New users today, who have lower incomes and lower levels of educational attainment than those of yesterday, may be less disposed toward embracing technology than their earlier counterparts. Section VI. explores possible reasons for the reluctance to embrace the Internet, focusing on heightened concerns about online privacy as the reason.

III. The Internet’s Newcomers

Who are the people that fall into these categories of Internet users and are they different in 2000 than they were in 1998? A large part of the story of new users in 2000 is that they are mostly young women and more enthusiastic about the Internet than men who are new to the Internet. Slightly more than 1 in 4 women on the Internet, or 26%, are Instant Acolytes compared with 19% of men on the Internet who are Instant Acolytes; looked at differently, almost three out of five (58%) Instant Acolytes are women. Of people who have come online in the year prior to March 2000, 54% were women. Moreover, Instant Acolytes are more likely to go online from home than other user categories, suggesting that the Internet is becoming a home-based information/entertainment tool, and is less of an extension of work or school.

Instant Acolytes

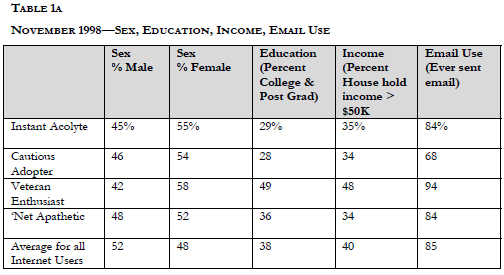

November 1998: This group of users is more female, less educated, and with a lower income than the overall Internet population of 1998. Women make up 55% of Instant Acolytes versus 48% of all Internet users at the end of 1998. Only 29% of this group has college or post-graduate degrees, compared with 38% of all users, and 35% of 1998 Instant Acolytes have household incomes over $50,000 versus 40% for all Internet users. Nonetheless, at least by one measure of Internet activity, Instant Acolytes have taken to the Internet with enthusiasm comparable to the larger Internet population; 84% of Instant Acolytes report using email and 85% of all 1998 Internet users report the same.

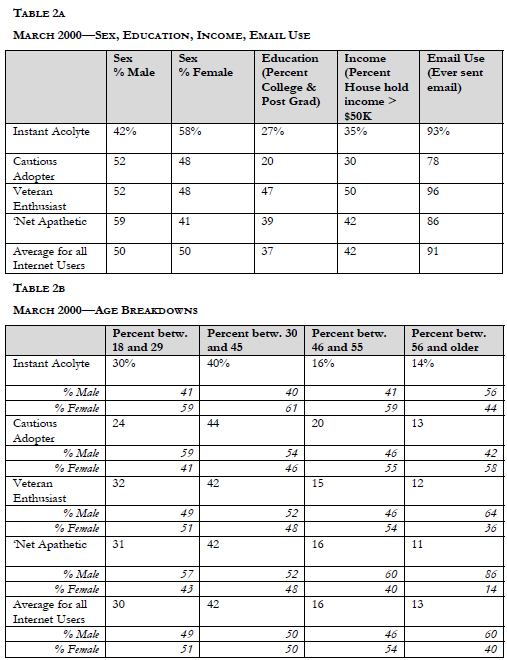

March 2000: Like their earlier counterparts, the Instant Acolyte 2000 group is more female, less wealthy, and less educated than the overall Internet population of March 2000. As already noted, women comprise 58% of Instant Acolytes in early 2000 versus 50% of the entire Internet population. Slightly more than 27% of this group has college or post-graduate degrees compared with 37% of all Internet users. And 35% of Instant Acolytes have household incomes over $50,000 as opposed to 42% of all Internet users. Email is an equally popular Internet activity across both groups; 91% of Instant Acolytes are email users versus 93% of all Internet users in March 2000.

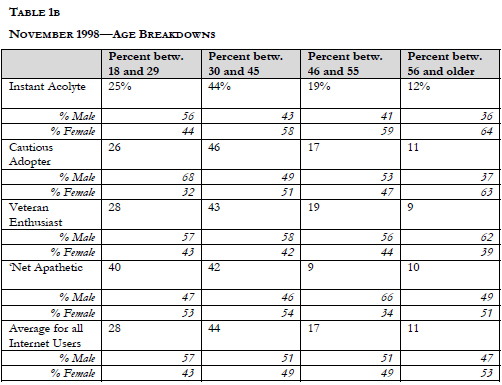

Discussion: The key difference between Instant Acolytes in 1998 and 2000 involves young women, specifically those between ages 18 and 29. Among Instant Acolytes between 18 and 29, 44% were women in 1998, but 59% were women in 2000. Women between age 30 and 45 were also prominently represented among Instant Acolytes; 61% of Instant Acolytes between 30 and 45 were women in 2000 versus 57% in 1998. At the other end of the age spectrum, women over 56 years of were quite enthused by the Internet in 1998, with 64% of Instant Acolytes over 56 being women. In March 2000, only 44% of Instant Acolytes in the “over 56” age group were women.

Cautious Adopters

November 1998: This group looks about the same as the overall Internet population in terms of gender breakdown (46% of Cautious Adopters are women compared with 48% of all Internet users), but Cautious Adopters are less educated and wealthy than the average user. Thirty-four percent of Cautious Adopters have household incomes over $50,000 in contrast to 40% among all users, and 28% have college or post-graduate degrees versus 38% for all Internet users. A striking contrast within age groups comes in the 18-29 cohort; 68% of Cautious Adopters in this category are men, with the remaining 32% women. Older women are more likely to be Cautious Adopters than their male counterparts; 63% of Cautious Adopters over age 56 are women. With respect to email use, 68% of Cautious Adopters have used email (the November 1998 average is 85%), with 72% of women and 65% of men saying they have used email. The gap in email usage suggests that caution translates into less Internet use, since email is the Internet’s most popular application.

March 2000: The Cautious Adopter of 2000 is slightly more likely to be male than the overall Internet population (52% are male versus 50% for the Internet population), less wealthy, and rate substantially lower on educational attainment. Just 30% of this group makes more than $50,000 per year compared with 42% of the overall Internet population. Only 20% of Cautious Adopters have college or post-graduate degrees versus 37% of the entire Internet population. As with the 1998 group of Cautious Adopters, among young Cautious Adopters there are more men than women; 59% of Cautious Adopters between ages 18 and 29 are men and 41% are women. The pattern reverses with age; 58% of Cautious Adopters over age 56 are women and 42% are men. Not surprisingly, the mainstay Internet application—email—has not strongly captured this group’s imagination; 78% are email users (in contrast to the 93% average), with 81% of men and 74% of women reporting having used email.

Discussion: While Cautious Adopters are very similar in 1998 and 2000, two points stick out in the 2000 group, namely education levels and email use. The 17-point deviance from the average for college and post-grad educational attainment for the 2000 group (as opposed to 10 points for 1998) may reflect the declining pool of well-educated new users as Internet penetration rises. Email use among Cautious Adopters in 2000 is a puzzle, with men reporting higher email use than women. The Pew Internet Project has found that women are more frequent emailers and like it better. Fully 92% of women have used email and 46% report having used it “yesterday”, while 91% of men have used email and 40% used it “yesterday.” And 78% of women say they look forward to checking their email versus 62% of men.

Veteran Enthusiast

November 1998: Unsurprisingly, the Veteran Enthusiasts are, as a group, wealthier, more educated, and more male than the average Internet user of the latter part of 1998. Nearly 58% of Veteran Enthusiasts are men, as opposed to 52% of men overall among the online population. Forty-nine percent of this group have college or post-grad degrees compared with the 38% average. And 48% have household incomes over $50,000 versus 40% of the overall Internet population. Veteran Enthusiasts also embrace email; 94% count themselves as email users (with no difference in usage rates between men and women), a figure 9 points higher than the average for Internet users.

March 2000: The March 2000 Veteran Enthusiasts are very much like the November 1998 group, which is understandable because veteran enthusiasts of two years ago are today’s veteran enthusiasts. They are slightly more male (52% are males versus 50% of the entire Internet population), wealthier (50% have household incomes over $50,000, eight points higher than the average), and more educated (47% graduated from college or beyond, ten points higher than the average for the Internet population). 1998’s Instant Acolytes are probably reflected here, 55% of whom were female, and with the fervent embrace of email by women, it is not surprising that women have increased their representation among Veteran Enthusiasts by March 2000. Within age categories, older men seem to be particularly ardent ‘Net users. Among Internet user over the age of 56, 60% are men; among Veteran Enthusiasts over age 56, 64% are men. Finally, Veteran Enthusiasts are active emailers; 96% of all Veteran Enthusiasts use email, 97.2% of women and 95.7% of women.

‘Net Apathetic

November 1998: Users who have been online for more than 2 years but who say that they would not miss the Internet are more likely to be female and less wealthy than the average Internet user, but about as well educated. Fifty-two percent of the ‘Net Apathetic are women (in contrast to 48% of women in the entire Internet population at the end of 1998), and 34% have household incomes over $50,000 versus the 40% average. However, 36% of the ‘Net Apathetic have college or post-grad degrees, nearly the level as all Internet users (38%). Interestingly, the ‘Net Apathetic are on balance younger than the overall Internet population. Fully 40% of the ‘Net Apathetic are between 18 and 29, compared with 28% in that age group in the Internet population at large. This cohort is more likely to be female; women are 43% of the December 1998 Internet population between ages 18 and 29, while women make up 53% of the ‘Net Apathetic in the 18-29 age group. In terms of email use, 84% of the ‘Net Apathetic are email users, 85% of men and 83% of women.

March 2000: The typical ‘Net Apathetic user for early 2000 is very much like the average Internet user, although the ‘Net Apathetic is more likely to be male and better educated than the average Internet user. While half of all Internet users were men in March 2000, 59% of the ‘Net Apathetic are men. Fully 39% have college or post-graduate degrees (versus 36% of all Internet users), and 35% of the ‘Net Apathetic have attended some college, as opposed to 31% of all Internet users. Yet 42% of the ‘Net Apathetic have household incomes above $50,000, and that matches the number for all Internet users. Unlike the 1998 ‘Net Apathetic group, youth is not an issue; 31% of the ‘Net Apathetic are between 18 and 29 for the March 2000 group versus 30% of all Internet users in the 18-29 age bracket. There is simply a general pattern in all age groups of more men than women falling into the ‘Net Apathetic category. Not surprisingly, the ‘Net Apathetic are less frequent email users than average; 86% report having used email, with no differences across gender, which is about 5 points below the March average. As discussed further below, the likely reason for this lower rate of email use has to do with access; the ‘Net Apathetic are less likely to have online access from home, which depresses Internet usage in all categories of activities, not just email.

The following tables summarizes the demographic characteristics of the user types in November 1998 and March 2000.

Summary of Demographic Characteristics by User Classification

Summary of Demographic Characteristics by User Classification

IV. What People Do Online

The only Internet activity considered above is email, but people do much more online than simply send email. As the Pew Internet Project has found, people surf the Web as frequently as they go online to check email.6 By comparing what Instant Acolytes do online to the average Internet user and the most enthusiastic veterans, we can gain a sense of what matters most to new users and make guesses as to how that might affect the Internet in the future. And by comparing what new users today value on the Internet with what new users valued in 1998, we can get a sense of how Internet users are changing, and speculate about how the Internet may evolve.

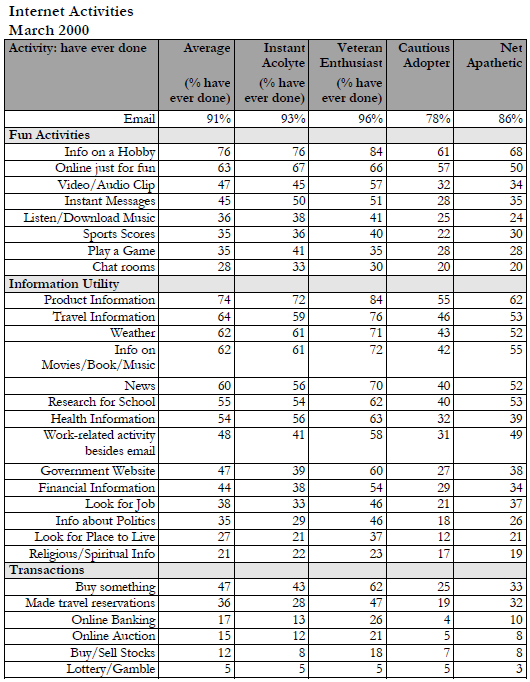

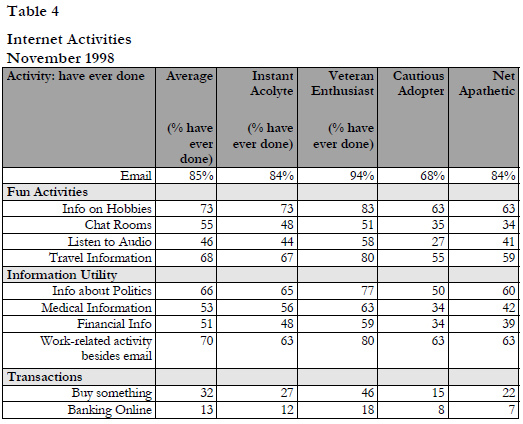

The following tables compare Internet activities for Instant Acolytes, Veteran Enthusiasts, Cautious Adopters, the ‘Net Apathetic, and the overall average for March 2000 and November 1998.

Table 3

In both tables, the activities are divided into three categories, “fun” activities, activities in which the Internet is used as an information utility, and transactions. For March 2000, the Instant Acolytes engage in “fun” activities to an equal or greater extent than the average user in 7 of 8 activities. In a number of cases, such as going online for fun, playing a game, or going to a chat room, Instant Acolytes are more active than Veteran Enthusiasts. When it comes to using the Internet as an information utility, Instant Acolytes approach the frequency of use of average users in most areas, although their lower-than-average usage levels are notable in looking for financial information, political information, or visiting government websites. Veteran enthusiasts substantially outpace Instant Acolytes in using the Internet as an information utility, with 10 to 20 point gaps in a number of categories. The interesting exception is health care information, the one category in which Instant Acolytes’ usage rate exceeds the average and (setting aside spiritual information) the gap between Instant Acolytes and Veteran Enthusiasts is narrowest (7 points).

Turning to transactions, it is clear that even the most enthusiastic new users are reluctant to make purchases online. Instant Acolytes lag behind the average in all categories, and the gap between this group and Veteran Enthusiasts is wide in all activities, except gambling. Length of time on the Internet is strongly associated with willingness to conduct Internet transactions, and perhaps the most compelling evidence of this is seen in a comparison of Cautious Adopters with the ‘Net Apathetic. The Cautious Adopter, the new user who would not miss the Internet, is nonetheless about as likely to engage in “fun” Internet activities as the ‘Net Apathetic, who has been on the Internet a while but has not become enamored of it. But when it comes to transactions, people in the ‘Net Apathetic category are more frequent online purchasers and far more likely to make online travel reservations or bank online than Cautious Adopters.

The November 1998 results follow the same general pattern as the March 2000 results, with the important differences being that Instant Acolytes lag further behind Veteran Enthusiasts in fun activities and seem somewhat more active in using the Internet as an information utility, both in absolute terms and relative to Veteran Enthusiasts. All users were more likely to go online to look for political information—perhaps because the 1998 poll was taken during an election season—with Instant Acolytes closer to Veteran Enthusiasts’ usage rate than in 2000. Instant Acolytes are 10 points more likely to go online for financial information in 1998 than 2000, while Veteran Enthusiasts are 5 points more likely. The results for “work-related activity besides emails” are also telling. Internet users in general engaged in this information-gathering activity at a much higher rate in 1998 versus 2000, with 70% of 1998 users having done this compared with 48% in 2000. With high usage rates across all user categories in “work related activities”, Instant Acolytes lag behind Veteran Users and the overall average. Nonetheless, the gap in the likelihood in going online to do a transaction is wide, with 46% of Veteran Enthusiasts having gone online to buy something compared with 29% for Instant Acolytes.

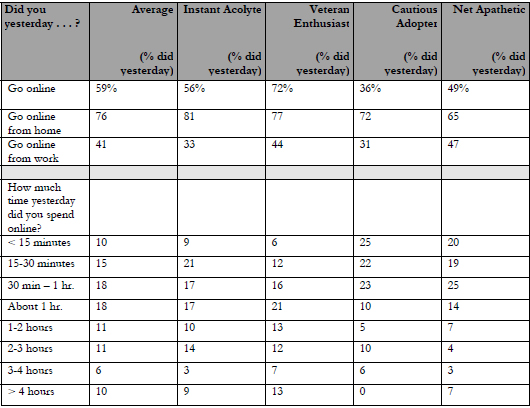

Another element that influences the usage habits of these user classes is frequency of Internet use, amount of time spent online, and where people go online from. By asking what people did online yesterday, the Pew tracking poll sheds light on these factors. The following table summarizes the findings for the four categories of Internet users.

Table 5

Several distinctions among user classes are evident:

- For Instant Acolytes, the Internet’s most enthusiastic new users, the ‘Net is a home-based phenomenon to a much greater extent than it is a work-based activity.

- The ‘Net Apathetic have folded the Internet into their lives to a lesser extent than other classes because the Internet is more of a work-based activity for them than it is for other classes. Also, this group is about half as likely to spend 2 or more hours online than the average.

- Although Cautious Adopters are less likely than any class to have gone online yesterday, they are equally as likely to have spent an hour or more online as the ‘Net Apathetic (21% of both groups spent an hour or more online “yesterday”).

- What separates the Cautious Adopter from the ‘Net Apathetic is home-based access. The Cautious Adopter is more likely to go online from home, and much less likely to go online from work than the ‘Net Apathetic. With Cautious Adopters going online from home about as often as the average user, their usage might be expected to rise over time.

- Veteran Enthusiasts obviously rate most highly in most categories; this group has folded the Internet into their daily work routine to a greater extent than new enthusiasts.

Discussion

A number of conclusions emerge from the preceding analysis. First, new users seem most comfortable at the outset with fun activities on the Internet. Second, fun activities seem to engage people to a greater extent today than they did two years ago, when the information utility aspect of the Internet held a stronger attraction (relative to the average and Veteran Enthusiasts) among Instant Acolytes than it did in March 2000. The evidence suggests that people go online today for fun, while two and a half years ago, fun was an important reason, but practical applications held greater sway. That is probably because new users today are more likely than veterans to go online from home; the Internet is a fun activity (relative to the past) that is to be done at home more than at work. Finally, new Internet users—whether enthusiastic about the Internet or not—are reluctant to complete transactions online.

V. The “Transactions Divide” and Internet Usage

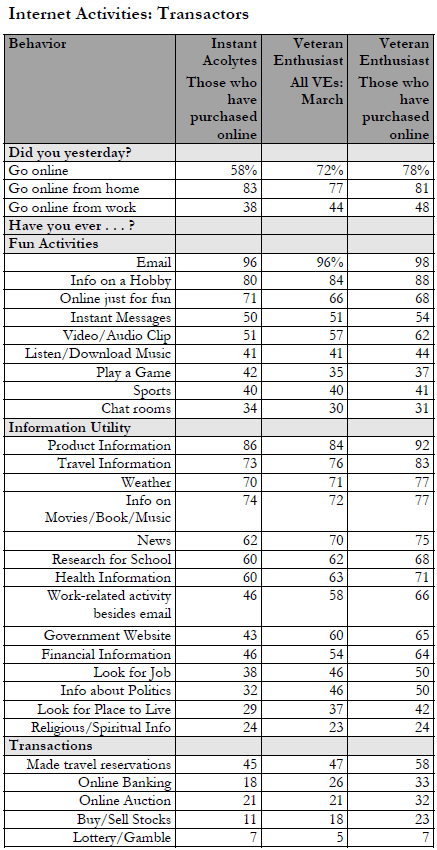

Although newcomers to the Internet are reluctant to do online transactions, once they cross the “transactions divide,” how do they compare with long-time Internet users? To explore this question, I examined the Internet usage habits of a subset of Internet users who said that they have ever bought something online. As noted in Table 3, 47% of Internet users in the March sample have ever bought something online, and of those 794 Internet users who have purchased something online, 165 are Instant Acolytes. Here’s how the frequency of their Internet activities compares with Veteran Enthusiasts profiled in Table 3, and Veteran Enthusiasts who have ever bought anything online.

Table 6

The table suggests that Instant Acolytes who have bought something online are in many ways like veteran users who have over time woven the Internet into their daily lives. For “fun” activities, Instant Acolytes who have taken the step to purchase something over the Internet are more active users than veterans in most cases. Looking at “information utility” activities, Instant Acolyte purchasers match Veteran Enthusiasts in a number of categories. For information utilities that have professional, financial, or news gathering overtones, Instant Acolyte purchasers lag behind Veteran Enthusiasts. With respect to transactions, it would seem that Instant Acolytes who have made an online purchase are comfortable with relatively less important online transactions, such as auctions or making travel reservations. For transactions that involve money management, which presumably are of larger magnitude or importance than auctions or travel expenditures, Instant Acolytes show lower levels of activity than Veteran Enthusiasts. Finally, it is important to note that 60% of Instant Acolyte purchasers are women. That is slightly more than the overall number for Instant Acolytes (58%) and reinforces the point that women are enthusiastic and active new users of the Internet.

The table also shows that Veteran Enthusiasts who have made an online purchase are the most active Internet users, with these users being most active in transactions of all kinds. In a number of “fun” activities, however, such as going online just for fun, playing a game, or going to chat rooms, it is notable that Veteran Enthusiasts purchasers and Instant Acolyte online purchasers are equally active users.

Between this section and the preceding one, we see that generally Instant Acolytes are active Internet users in many respects except when it comes to conducting online transactions. But once Instant Acolytes have crossed over into the world of online transactions, they are nearly as active on the Internet as veteran users, and more active in “fun” uses of the ‘Net. The choice to conduct an online transaction is tantamount to a choice to take one’s Internet use to the next level. What determines whether a user makes the choice to transact online? The next section explores reasons this question.

VI. Privacy Worries and Internet Transactions

A sensible guess as to why new users—those who quickly embrace the Net or not—might hesitate to conduct transactions over the Internet is that these users are concerned about theft of credit card numbers or other personal information in the course of the transaction. The Pew Internet Project poll shows that this is the case.

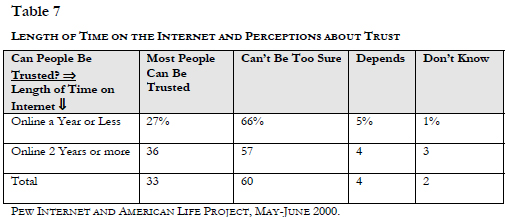

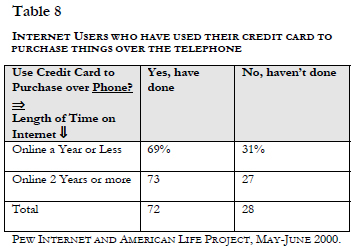

Internet users who have been on the ‘Net for a year or less report lower levels of trust than users who have been online for two or more years. When asked whether most people can be trusted, 36% of Internet users online for two or more years answered “yes” versus 27% of users online for a year or less. In terms of using their credit card to purchase things on the telephone, veteran users are only slightly more likely to do this than new users. Seventy-three percent of all veteran Internet users have used their credit cards to make purchases over the telephone compared with 69% of users online for a year or less. Yet new users are much more likely to be concerned about credit card theft when making telephone purchases. Only 16% of veteran Internet users reported worrying “a lot” about credit card theft during phone purchases compared with 27% of veteran users.

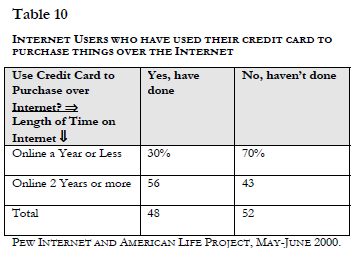

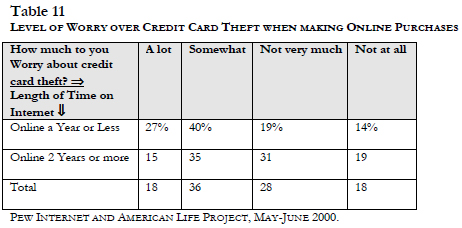

Substantial gaps between new and veteran users open up when looking at people’s online purchasing behavior and concerns about credit card theft. Veteran users are almost twice as likely to have ever used their credit card to buy things on the Internet; 56% of users online for two or more years have used a credit card to purchase something on the Internet versus 30% of users online for a year or less. Conversely, new users are about twice as likely as veteran users to be worried a lot about theft of credit card numbers when making Internet purchases; 29% of new users say they worry a lot about Internet credit card theft compared with 15% of veteran users. In terms of expressing “some” concern about Internet credit card theft, 40% of new users say they are somewhat concerned versus 35% of veteran users.

Thus, although new Internet users are somewhat less trusting in general than veteran users, this lower level of trust translates into only modestly lower levels of telephone purchasing behavior, but substantially lower online purchasing behavior. As noted above, new users are about half as likely to send credit card information over the Internet for purchases, but lag only 4 points behind veteran users in telephone purchases (at a high level of having ever made such purchases for new and veteran users). Even with approximately same “worry rate” about credit card theft for phone and online purchases, new users’ inexperience on the Internet results in a reluctance to engage in ecommerce.

The following tables summarize poll findings on privacy and trust and length of time on the Internet.

VII. Policy Implications and the Internet’s Future

One inescapable conclusion is that Instant Acolytes are different from average and experienced Internet users. They are more likely to be women who go online from home, with lower levels of education and income, and with a preference to surf the Internet to a variety of “fun” sites. What, if anything, should policymakers do differently given that today’s most enthusiastic new Internet users depart from the traditional stereotype of the educated white-male Internet user? The answer falls into two categories: a) privacy, and: b) content. New Internet users, as will be discussed, have different attitudes toward privacy than experienced users. When it comes to online content, Instant Acolytes, with their focus on “fun” sites, value a variety of Internet content as they explore the ‘Net. Policymakers may want to nurture a climate in which a wide range of content is accessible on the Internet.

Privacy

With new Internet users registering clear worries about the privacy and security of their Internet transactions, privacy policy looms large in thinking about possible barriers to the Internet’s future growth. Indeed, when asked policy-oriented questions about privacy, new users showed a stronger tendency to entrust government in setting the rules for privacy and less of an inclination to let online companies have free reign with their personal information. The Pew Internet Project poll asked people who should have the most say over how Internet companies track people’s online activities. Only 17% of Internet users responded that the government should, while 8% said Internet companies should and 71% said individuals should. Put another way, only 1 in 4 Internet users thought that either the government or Internet companies should set the rules on how Internet companies track people’s personal information, but new users in this subset of Internet users—by a margin of 77% to 62%–were more likely to say they wanted the government setting the rules, not Internet companies.

With respect to “opt in” approaches to use of personal information, whereby online sites must explicitly receive permission from users before collecting information, 86% of all Internet users said they agreed with the proposition that Internet companies should ask people for permission to use personal information. Interestingly, the longer a person has been online, the more likely they are to favor “opt in”; 88% of users online for two or more years favored “opt in” versus 82% of people online less than a year. At present, however, the Federal Trade Commission has adopted the “opt out” approach endorsed by the Network Advertising Initiative, a consortium of Internet advertising companies.

What is notable about people’s attitudes about “opt in” is that it appears to be the culmination of a series of rational choices and behaviors vis-à-vis the Internet. The longer people have been online, the more likely it is that they shop online. Although people worry about credit card theft in the course of transactions (54% say they worry “ a lot” or “some” about this), 15% have experienced credit card theft of any sort, and of this group, just 8% say the theft occurred over the Internet. That is, less than 1% of all Internet users have had their credit card number stolen over the Internet and only 3% of Internet users report ever having experienced fraud on the Internet of any kind. The convenience and other benefits of online shopping (e.g., lower prices, greater choice, ease of gathering product information) outweigh the cost of credit card theft (which occurs infrequently online). If that weren’t the case, it is unlikely that more experienced users would be more frequent purchasers of products over the Internet.

But the perceived and real costs of releasing personal information are evident to Internet users. Only about a quarter of Internet users (27%) believe that Web companies’ tracking of their activities is a helpful thing (e.g., because it helps the company provide information that matches their interests). Fully 54% say such tracking is harmful because it violates their privacy. And a substantial number bear the burden of such tracking in their email in-boxes; about 3 in 8 (37%) of Internet users report receiving unwanted “spam” email messages, 70% of which are sales solicitations. It is no wonder that more experienced Internet users prefer “opt in”; they see a significant cost to allowing companies to collect their personal information.

Because Internet users see a cost in making their personal information freely available to Web companies, it makes sense that they—especially Internet purchasers—want to choose whether that information is made available. Fully 89% of Internet users who have bought things online favor an “opt in” approach to privacy versus 79% of all Internet users. Online purchasers are willing to pay the cost of the product purchased, but nothing more. This also shows that online purchasers understand that their personal information has value. If Web vendors want personal information about the purchaser, the “opt in” group of Web buyers—the vast majority of Web shoppers—is saying that they must at least ask permission. And if the answer is no, under “opt in” the burden then falls back to the online vendor to provide an incentive to Internet consumers to give up something of value.

Online Content

New users are drawn to the Internet by “fun” activities, and it seems to be only a matter of time (assuming their privacy worries are adequately addressed) until they become active in Internet transactions. The implication of new users’ preference for doing fun things online is that they value a lot of options in how they may have fun or gather information. Indeed, it may be people’s “search and learn” mode early in their online lives is what enables them to trust the technology enough to begin doing online transactions. The openness of the Internet is the essence of the “search and learn” approach to engaging with the Web. The potential of Internet service providers owned by cable companies to restrict access to Internet content flies in the face of a “search and learn” approach by new users. Whether such possible restrictions would dampen the spirits of new users is another question and technology and the marketplace may be rendering such concerns obsolete. Peer-to-peer Internet search technology is a powerful new tool to circumvent central servers that may serve as bottlenecks to content distribution. And, with recent announcements by AT&T that it would allow open access to its cable Internet content, the industry is apparently getting signals from the market that open access is valuable to consumers.

Nonetheless, at one time at least, the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) expressed a bias toward encouraging investment in new broadband infrastructure, a bias that would supersede encouraging open access. As FCC Chairman William Kennard commented during litigation by cities to force AT&T to transmit non-AT&T provided content on its high-speed Internet service, the Commission would not weigh in on the side of open access because this might dampen investment incentives to build broadband plant. With the jurisdictional aspect of the question settled,7 the FCC should adopt a position that encourages open access to a wide variety of Internet content. At a minimum, the findings here suggest that a “first do no harm” policy posture that presently seems to be the mantra for broadband investment should extended to access to Internet content.

The Internet’s Future

In contemplating how today’s Instant Acolytes might shape the Internet’s future, the early history of the telephone is instructive. As Claude Fischer notes, the Bell System’s early marketing efforts focused on the telephone as an item for businesses and professionals.8 To the extent it was used at home, early adopters were generally men who needed it to conduct business or respond to emergencies (i.e., doctors). When it became clear that women were heavy telephone users, marketers re-targeted their efforts to women as “chief executives” of the household. In creating uses for the telephone, telephone marketers envisioned women using it to manage the household and purchase groceries. However, as Fischer point outs, women used the telephone primarily for sociability, something that came as a surprise to industry marketers. Rural women especially used the telephone to decrease social isolation.

With Instant Acolytes’ inclination to go online from home and for fun, the Internet may be evolving much like the telephone into a domestic tool for sociability used more heavily by women. Rather than a mysterious technology that is the province of men, the Internet is on the cusp of becoming a household appliance whose applications are as much social as transactions-oriented. While Instant Acolytes, females or males, will engage in more transactions the longer they are online, the evidence presented here (and from the early history of the telephone) suggests that the social uses of the Internet will be as worthy of scrutiny as the commercial ones. Again, this argues for a policy climate in which a wide diversity of content is allowed to flourish.

The trends toward the Internet as tool for sociability are likely to shape, as well as be shaped by, the coming explosion in bandwidth capacity and the growing variety of Internet access appliances. As the Internet moves out of the home office and into the family room or kitchen, means of Internet access will have to serve people’s desires for entertainment, real-time communication with others (either audio or video), and provide a wide choice of information options. Applications such as buying things online and managing personal finances online will continue to be important to Internet users. But shared experiences distributed among different users at different locations may take on a larger meaning for users. Today’s Instant Acolytes, at least, are signaling that they see the Internet as a tool for entertainment in the home and interactive communication such as instant messaging and chat rooms.

Tomorrow’s Instant Acolytes will look a lot like today’s, although with grayer hair. Fully 55% of the current non-online population being women, with one-third of the non-online population women over age 50. This group is somewhat less trusting than the overall population (29% of this group says that people can be trusted versus 33% of people online), and with the proliferation of entertainment websites, will probably value diversity of content as much as today’s Instant Acolyte. While the marketplace will drive much of what is available to them, policymakers would be wise to set rules that provide assurances about the privacy of Internet transactions and provide a climate in which a rich variety of content is available to those in “search and learn” mode on the Internet.