Part 1: An overview of the digital divide

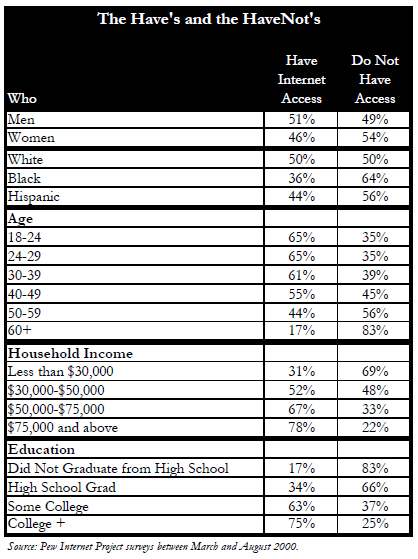

Half the adults in America (those 18 and over) do not have Internet access. That is more than 94 million people. Previous studies on the “digital divide” have highlighted the fact that those without Internet access are less well off financially and are more likely to be minorities. The surveys of the Pew Internet & American Life Project find that to be true. More than three-quarters (78%) of those who live in households earning more than $75,000 have Internet access. By contrast, just 31% of those who live in households earning less than $30,000 have access. Non-users are less likely to be employed than Internet users. Some 42% of those not online have full-time jobs and 9% have part-time jobs, compared to 66% employed full time and 14% part time for Internet users.

In addition, whites are notably more likely to have Internet access than those in other racial and ethnic groups. Some 50% of whites have access to the Internet, compared to 36% of blacks, and 44% of Hispanics. In most respects, these racial and ethnic variances are explained by income. Relatively well-to-do whites, blacks, and Hispanics are online at roughly the same rates. Some 78% of whites in households earning more than $75,000 are online. Fully 79% of Hispanics in similar economic circumstances are online and 69% of blacks in those types of households are online. At the other end of the economic spectrum, 68% of whites in households earning less than $30,000 are not online, while 75% of blacks in similar households are not online, and 74% of Hispanics are not online.

Those not online have less education than Internet users. More than two-thirds (71%) of non-users have a high school education or less, compared to 32% of Internet users who have that level of education

There are other influences at play in the offline population. First, age is a major factor. The older a person is, the more likely it is that she does not have Internet access. Second, non-users have a variety of concerns about the Internet that extend beyond the expense of purchasing a computer and paying for online service. Those concerns center on the online environment. Generally, non-users believe the online world is not very useful or hospitable. They are also concerned about the dangers that lurk on the Web, and about their ability to maintain their privacy online. Third, the type of community where a person lives – rural, urban, or suburban– is a major indicator of whether she has Internet access.

And while the Pew Internet & American Life Project reported in May that women have gone online in droves in the past 6 to 9 months, a disparity still exists between men and women online as percentages of their own populations because women make up a greater portion of the U.S. population. Part of the reason more women do not have Internet access is that women make up a large portion of the population of elderly in the United States and that is also group most likely to be outside the Internet population. Thus, 55% of all those not online for any reason are women, and 45% are men. Of those not online, 51% are people 50 and over. Within this older cohort, the tilt toward women is even stronger – 59% of those this age who are not online are women.

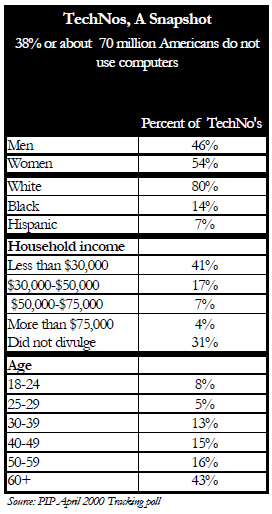

Another issue involves computer use. Non-computer users make up thirty-eight percent of the American population. Some 54% of them are women, and 46% are men. An interesting subgroup of non-Internet users is made up of those who use computers but do not go online. Some 14% of those without Internet access have computers. Fifty-seven percent of this computer-but-no-Internet cohort are female and there is a relatively large proportion of African-Americans in this group. Some 13% of those who do not use the Internet have used it in the past and stopped.

Part 2: Who’s planning to go online and who’s staying away

All those factors affect the degree to which non-users are interested in going online. The majority of those without Internet access say they are likely to stay away from the Internet. A third of non-users (32%) say they definitely will not get Internet access. Another 25% of non-Internet users say they probably will not venture online.

Three distinct groups of non-Internet users are evident when they are questioned about their intentions. The Eagers, who make up 41% of those without Internet access, say they definitely or probably will go online. The Reluctants, about 25% of the non-user population, say they probably will not go online. The Nevers, some 32% of the non-user group, say they definitely will not be going online.

- The Eagers

This group looks quite a bit like those who have just gotten Internet access. The Eagers cohort is weighted a bit towards women, Hispanics, and African-Americans. Compared to Reluctants and Nevers, Eagers have the largest proportion of those with relatively high household incomes, and those with relatively high levels of education.

About 45% of Eagers are male and 55% are female. Some 41% of the men not currently online say they would like to go online and 40% of the women not online want to get Internet access. About half of Hispanics currently without Internet access are interested in going online and a slightly smaller percentage of African-Americans say the same thing. Roughly 40% of non-online whites say they plan to get on the Internet.

Many Eagers are young. Some 65% of those under age 30 who do not have Internet access now say they want to get it. The same percentage of those between ages 30 and 50 cite the same desire to get Internet access. In contrast, only 37% of those between the 50 and 64 hope to go online and just 15% of those over 64 report the same aspiration.

Many of the Eagers have some experience with college. More than half of those with college degrees or with some college experience who are not online say they want to go online. By comparison, just 27% of those without high school diplomas say they want to go online.

Eagers also have relatively high incomes. Fully 71% of those in households earning more than $75,000 and who don’t have Internet connections say they plan to get such connections, and 62% of those with incomes between $50,000 and $75,000 report the same aspiration. By contrast, 38% of those earning less than $30,000 say they hope to go online.

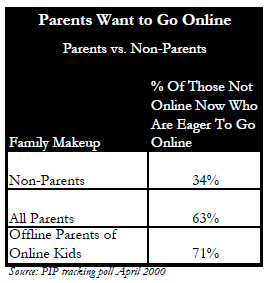

Parenthood seems to push people online or at least encourage parents to think about getting Internet access. About 44% of parents with children under 18 are not online, compared to 57% of non-parents. Fully 63% of all not-online parents are Eagers and say they probably or definitely will go online at some point.

The Eagers also are the most intrigued and least intimidated by the online world. Compared to the other groups, Eagers feel that they are missing out by not being online and that probably explains much of their motivation to get Internet access. An overwhelming 88% believe that the Net would help them find information. They also don’t think that the Internet is confusing or hard to negotiate. They did express concerns, however, that the Internet is too expensive and dangerous, which might explain why they have not yet taken the plunge.

- The Reluctants:

Of those who say they probably will not get Internet access 56% are women. Roughly one-quarter of offline men and one-quarter of offline women fall into the Reluctants camp. When the frame of reference is race and ethnicity, Reluctants are a bit more likely to be white – 26% of whites say they probably won’t go online; 19% of blacks say that; and 23% of Hispanics say that.

Reluctants are notably older as a group than the Eagers. Almost two-thirds (64%) are over age 50 and just 9% of them are under 30.

Reluctants also have less education than those eager to go online. More than three-quarters of this group (76%) have a high school diploma or less. And 65% of Reluctants live in households making $50,000 or less.

Some 60% of Reluctants say they don’t think they are missing a thing by not being online. Many say they think the Internet is confusing and hard to use and that the online world is dangerous and too expensive.

- The Nevers:

Members of this group say they definitely will not go online. The most important factors at work here are the age of the Nevers, their education level, and their household income levels.

Some 57% of Nevers are women, 43% are men. About a third of all offline women say they will definitely not go online and about 31% of men say that. Whites and blacks fall equally into this camp with three in ten in each race reporting they have no desire to go online. About a quarter of Hispanics say the same thing.

The Nevers are much older as a group than the Reluctants, not to mention the Internet user population. Fully 81% of Nevers are over 50. Nearly 56% of those over age 65 say they will definitely not go online, compared to just 6% who say they definitely plan to go online. Fully 82% of the Nevers have a high school diploma or less and 43% of this group earn less than $30,000.

When asked their opinions of the Internet, the Nevers are the most unenthusiastic about the Internet of those surveyed. They are also the most likely to express no opinion, which suggests that many have not concerned themselves with the Internet phenomenon. It doesn’t matter whether the question they are asked relates to a potentially bad trait of the Internet or a good trait of the Internet. Many senior citizens consistently shy away from taking sides. It is fairly evident that the Internet is a technology that has not engaged them.

Only 19% of Nevers felt that by not being online they are missing out on something. The Nevers also are strong backers of the view that the Internet is dangerous (52% agreed with that thought), hard to use (33% agreed and 42% say they didn’t know) and expensive (32% agreed and 51% didn’t know). A modest plurality agreed (44% agreed, 32% disagreed) that the Internet would be helpful in locating information. But clearly, this limited appeal of the Web as an information utility is not strong enough to lure the Nevers.

Is there anything that could draw the Nevers online? We analyzed Internet users with similar demographic characteristics – that is, those with a high school diploma or less and those who are over 50. Like the Nevers, this group of users is predominately women (60%) and is also overwhelmingly white (93%). This group of Internet users likes email as much as the rest of those in the Internet population. Fully 90% of them (compare to 91% of all Net users) have used email. They are fairly light users of the Internet. The only activity they do at slightly elevated levels compared to other Internet is look for health information, which relates to the fact that the majority of this group is female. These Internet users like to take advantage of the entertaining online activities—searching for information on their hobbies and surfing just for fun. Other popular activities with this online group include checking the weather and researching (but often not buying) a product online. They also enjoy playing games online – about a third of them do that.

This analysis suggests that high-minded pitches about the civic, educational, or even commercial virtues of the Internet would probably not be enticing to those in the Never group. Rather, it suggests that Nevers might be more open to the idea of going online if they are convinced that the Internet is useful, entertaining, and not-too-difficult to use.

Two unique groups: The Net Dropouts and the InterNots

There are two other groups of non-Internet users worth noting: Net Dropouts, people who once had Internet access but are not now online, and InterNots, computer users who do not use the Internet. Generally, they are much less baffled by the Internet than other non-users, but many of them harbor concerns about the online world.

- Net Dropouts:

They make up about 13% of the not-online population. In some key respects, they are like Internet users. Net Dropouts are close to evenly divided between males and females, just as the gender ratio of the Internet population is about 50%-50%. The racial profile of Net Dropouts is weighted just slightly more towards minorities, but closely matches the profile of the U.S. population. And Net Dropouts are relatively young. However, they seem to have less education than Internet users and come from households with less income.

Many Net Dropouts cited changes in their lives as the reason they were no longer online. Some 21% say they no longer own a computer, and 14% say they had changed jobs. Another 11% cite the fact that access is too expensive and 9% say they found that the Internet wasn’t interesting or useful to them. Some 8% left the Internet over concerns about their privacy. (33% cited a variety of other reasons.)

- InterNots—Computer Users Who Aren’t Online

This group makes up 14% of the American population. InterNots’ attitudes towards the Internet reflect some reasons why they may not be online. Large numbers believe that the Internet is dangerous and expensive. Compared to the entire Internet population, they seem more likely to be members of minority groups and have less income in their households and their educational attainment is not as high as the Internet-user cohort.

Part 3: The gray gap

The generational story is a powerful one in examining those who are not online. Just 13% of those over age 65 have Internet access, compared to 65% of those under age 30. People 50 and over make up half of the non-online population. For some, economics holds the key. Some 29% of all non-users are retired and many are on fixed incomes. But the “gray gap” is not something that can be explained entirely by economics. A 65-year-old living in a household with more than $75,000 in income is three times less likely to be online than a 25-year-old at that same economic level. At the other end of the economic ladder, a 25-year-old in a household with $25,000 of income is twice as likely to be online than a 65-year-old at that same economic level.

One major factor for older Americans is their lack of contact with computers. Fully 57% of Americans over 50 do not use computers. One third of the entire non-computer population is women over 50. In contrast, computers are woven into the lives of many younger Americans. Some 78% of those under age 30 use computers at home or at work, while just 27% of those 60 and over have the same access. A 30-year-old in a household earning more than $75,000 is twenty percent more likely to use a computer than a 60-year-old in the same income bracket. Ninety-one percent of 30 to 39 year olds who earn $75,000 or more use computers, compared to 76% of those 60 and over who use computers and earn the same amount.

Again, even in the case of older Americans who are highly educated, a technology gap exists. Fully 28% of those over 50 who have college or graduate degrees do not have access or need for computers, while just 6% of those under 30 with college or graduate degrees do not use computers.

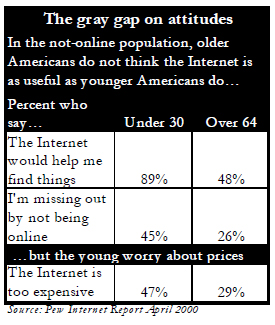

As a group, younger Americans who are not now online express more eagerness to go online and more positive views about the Internet than older Americans. Forty-five percent of those under 30 say they are missing something by not being online, compared to 26% of those over 64 who hold the same view. Fully 89% of those under 30 believe the Internet would help them find things, while only 48% of those over 64 say that. For younger Americans, the expense of the Internet is a major problem. About half of those not online and under the age of 30 say the Internet is too expensive. In contrast, the expense of the Internet is much less a concern to older Americans. Just 29% of those over 64 say they worry about that, and half of those in this age cohort didn’t respond to the question.

Older and younger non-Internet users have similar views on the most negative characterizations of the online world. Roughly half of each group believes the Internet is dangerous and roughly a third of each group find the Internet to be confusing.

However, older Americans are more likely than younger Americans to express concerns about privacy and the Internet. Fully 67% of those between the ages of 50 and 64 years old say they are “very concerned” about businesses and people they don’t know getting personal information about them or their families, compared to 46% of between 18 and 29. Older Americans also believe that Internet companies should ask people for permission to use personal information. Eighty percent of 50-64 year-olds say that.

Will these non-Internet users ever go online? In the case of older Americans, the chances are not as good as with younger Americans. Almost half of those who are over 50 and not online (46%) say they will definitely not go online, compared to just 12% of those under 50 who are hard core Internet resisters. In fact, 65% of people who are not online and under 50 say they will probably or definitely go online someday.

Part 4: What concerns non-users about the Internet; what intrigues them

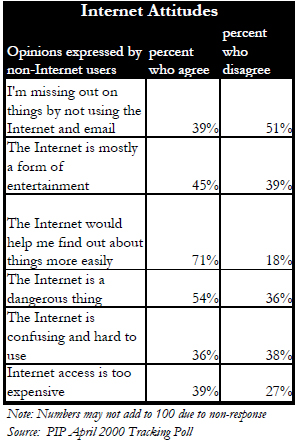

Those who do not have Internet access have an interesting mix of views about online life. On the one hand, they have pronounced fears about some aspects of the Internet world, but they also seem fascinated by other aspects of it. A rundown of their views:

It’s dangerous… More than half of non-users (54%) say they think the Internet is dangerous, and 11% profess no views. Those with the strongest opinions about the dangers of the Internet include people over 64 years old, and those with less than a high school education.

… and too expensive: About 39% of non-users believe this, 27% disagree, a full third of respondents say that they didn’t know. Non-users who are under age 30 are much more likely than their elders to hold this view – 47% in that age bracket subscribe to it. In addition, Hispanics are among the strongest proponents of this idea, as are those with less than a high school education. Interestingly, there are no significant differences among different income groups in response to this assertion.

I’m not missing out: Fully 51% of non-Internet users say they did not think they are missing anything by being offline, 39% say they thought they are missing out on things by not being online and another 10% say they didn’t know. There is strong consistency on this opinion among various groups. Those who felt a bit more frequently that they are missing something by not being online included minorities, people with college educations, and people in households earning between $50,000 and $70,000.

The Internet makes it easy to find information: Overwhelmingly, non-users of all kinds feel that the Internet would make it easier to find out about things. Some 71% reported believing this. Younger Americans, those with some college education, and those in households earning $75,000 or more are among the most inclined to have that view. Older non-users are significantly less likely than younger Americans to endorse the idea. Some 70% of those 50 to 64 years old and 48% of those 65 and over believe that being online would make it easier to find information, compared to the 85% of those 30 to 49 year-olds who endorse that view and a whopping 89% of those 18 to 29 who believe that.

It’s not that easy to use: Though the Web might make gathering information an easier task for many users, non-users are divided in their views. Some 38% say they don’t believe that the Internet is confusing or hard to use, 36% say it is confusing and another 26% say they don’t know. The group most likely to feel strongly that the Internet is hard to use is those with a high school education or less. Those most likely to think the Internet is easy to use included those under age 30, Hispanics, and those with college educations.

Part 5: A lag in rural areas and resistance in suburbs

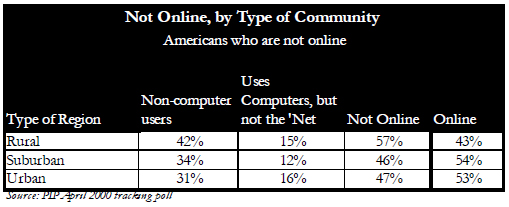

Where a person lives is also a factor in whether he is online or not. Residents of rural America are less likely than urban or suburban residents to have Internet access. Much of the difference between the three types of communities can be accounted for in rural citizens’ high rate of non-computer use. Some 42% of rural residents do not use computers, compared to 34% of suburbanites and 31% of urban dwellers. Of those who use computers but elect not to go online, the smallest group, by percent of population, is in the suburbs (12% of suburban dwellers do this compared to 16% of city folks and 15 percent of those who live in rural areas).

Urbanites who are not online are the most likely to say that they probably or definitely will go online (43% say that) while the suburbanites who aren’t online are the most likely to say that they won’t be going online (59% say they probably or definitely will not get Internet access). One possible explanation for these differences is that suburbanites have been exposed to idea of Internet access for relatively long periods of time compared to residents of some urban communities and rural regions. That means that those suburbanites who do not want Internet access have had a relatively long period of time to make up their minds not to log on and are firmer in their beliefs that the Internet has no great value to them.

For the most part, urban, suburban and rural non-users share similar attitudes towards the Internet. The one major difference between groups is on whether the Internet is confusing and hard to use. Pluralities of urban and suburban folk (41% and 40%) say that it isn’t confusing, while a plurality of rural dwellers (39%) say that it is confusing. All non-user groups show relatively high levels of belief that the Internet is dangerous, though rural non-users are more fearful (57%) than their urban (49%) and suburban (54%) counterparts.

Part 6: Connectedness and Trust

Those who do not use the Internet are less “networked” in their social lives, less trusting, and more concerned about their privacy being breached. These traits suggest that non-users as a group have a higher level of concern about interacting with others and fewer contacts with others. This suggests that they might be less attracted to the Internet than those already online because they feel less benefit can result from their being able to communicate efficiently and well with others. Much of this wariness of non-users is not surprising because the people who make up the non-user cohort, and particularly non-computer users, are from segments of the population such as older Americans, minorities, and those with less education that tend to be more suspicious and more concerned about their privacy than Americans overall.3

Some 20% of non-computer users say they have hardly any one or no one to turn to for help, compared to a mere 8% of Internet users who say that. A similar pattern holds true for whether Internet users and non-computer users visited with a friend or relative on any given day. Some 60% of non-computer users say they had visited with friends and relatives, compared with 72% of Internet users. Non-Internet users are more likely to believe that people will generally try to take advantage of them if given the opportunity—45% of non-users say that as opposed to 33% of Internet users.

Given non-users’ lack of trust and concern about privacy, it makes sense to think that some users aren’t online because they fear for their privacy. 8% of current non-users who were once online left because of privacy concerns, and 54% of non-users believe the Internet is a dangerous thing.