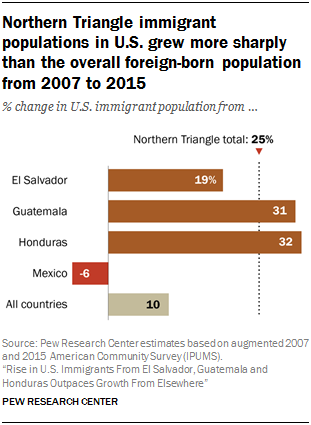

The number of immigrants in the United States from El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras rose by 25% from 2007 to 2015, in contrast to more modest growth of the country’s overall foreign-born population and a decline from neighboring Mexico.

During these same years, the total U.S. immigrant population increased by 10%, while the number of U.S. Mexican immigrants decreased by 6%, according to a Pew Research Center analysis of U.S. Census Bureau data.

One metric – the number of new immigrants arriving in the U.S. each year – illustrates dramatically how immigration trends from Mexico and the three Central American nations, known collectively as the “Northern Triangle,” have diverged in recent years. According to U.S. Census Bureau data analyzed by Pew Research Center, about 115,000 new immigrants arrived from the Northern Triangle in 2014, double the 60,000 who entered the U.S. three years earlier. Meanwhile, the number of new arrivals from Mexico declined slightly from 175,000 in 2011 to 165,000 in 2014.

Growing numbers of lawful as well as unauthorized immigrants from the Northern Triangle have made their way to the U.S. during the American economy’s slow recovery from the Great Recession (the recession began in December 2007 and officially ended in June 2009). Of the 3 million Northern Triangle immigrants living in the U.S. as of 2015, 55% were unauthorized, according to Pew Research Center estimates. By comparison, 24% of all U.S. immigrants were unauthorized immigrants.

Growing numbers of lawful as well as unauthorized immigrants from the Northern Triangle have made their way to the U.S. during the American economy’s slow recovery from the Great Recession (the recession began in December 2007 and officially ended in June 2009). Of the 3 million Northern Triangle immigrants living in the U.S. as of 2015, 55% were unauthorized, according to Pew Research Center estimates. By comparison, 24% of all U.S. immigrants were unauthorized immigrants.

Among the possible explanations for the recent rise in Northern Triangle immigration are high homicide rates, gang activity and other violence at home, according to a survey of migrants from the region. Other survey data indicate that Northern Triangle migrants are attracted to the U.S. for the same reasons as other migrants: economic opportunity and a chance to join relatives already in the country. The flow of money from the U.S. to the Northern Triangle is substantial: In 2015, Guatemala, El Salvador and Honduras were among the top 10 estimated remittance-receiving nations from the U.S., according to a Pew Research Center analysis.

More than a quarter million unauthorized immigrants from the Northern Triangle (roughly a fifth of unauthorized immigrants from the three countries) have temporary protection from deportation under two federal programs that the White House may phase out – Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) and Temporary Protected Status (TPS). The three Central American nations are also the starting points for many of the thousands of unaccompanied children apprehended along the U.S.-Mexico border since 2013.

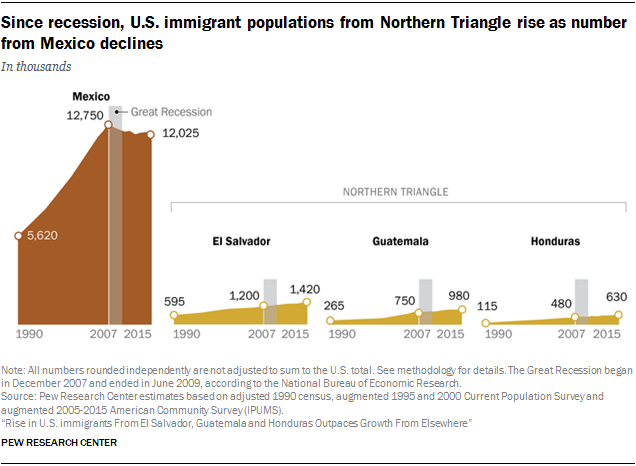

The Northern Triangle’s recent rise in U.S. immigration diverges from the pattern for Mexico, the largest source of U.S. immigrants. The immigrant populations from both Mexico and the Northern Triangle had been increasing since the 1970s. But overall growth in the Mexican-born population in the United States declined or stalled since 2007, fed by a decline in unauthorized immigrants and a rise in the lawful immigrant population.

The Northern Triangle’s recent rise in U.S. immigration diverges from the pattern for Mexico, the largest source of U.S. immigrants. The immigrant populations from both Mexico and the Northern Triangle had been increasing since the 1970s. But overall growth in the Mexican-born population in the United States declined or stalled since 2007, fed by a decline in unauthorized immigrants and a rise in the lawful immigrant population.

Heavily influenced by the decline from Mexico, the U.S. unauthorized immigrant population peaked in 2007 and fell over the next two years. It leveled off after 2009, because increases from the Northern Triangle and other regions balanced the continuing decline from Mexico. The U.S. lawful immigrant population overall grew over the decade, but not as sharply as it did from the Northern Triangle.

The 12 million Mexican immigrants living in the U.S. in 2015 far outnumbered those from the Northern Triangle, but the three Central American nations have grown in significance as a source of U.S. immigrants. In both 2007 and 2015, El Salvador ranked fifth among source countries, with 1.4 million immigrants in the U.S. in 2015. In those same years, Guatemala moved from 11th to 10th, with 980,000 U.S. immigrants in 2015. Honduras moved from 17th to 15th, with 630,000 immigrants in the U.S. in 2015.

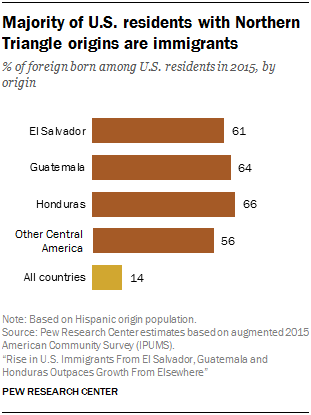

Immigrants account for most of the 4.6 million U.S. residents with origins in El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras and are the main driver of the group’s growth. By contrast, two-thirds of Mexican Americans were born in the U.S., and births to U.S. residents are the main contributor to the group’s population growth.

Immigrants account for most of the 4.6 million U.S. residents with origins in El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras and are the main driver of the group’s growth. By contrast, two-thirds of Mexican Americans were born in the U.S., and births to U.S. residents are the main contributor to the group’s population growth.

The recent surge in arrivals notwithstanding, most Northern Triangle immigrants have lived in the U.S. for at least a decade. Their households are more likely than those of immigrants overall to include minor children. And, as a group, their education levels and English proficiency are lower than those of U.S. immigrants overall.

Migrant motivations include economic opportunity

As for their reasons for moving, some limited survey data indicate that Northern Triangle migrants are attracted to the U.S. for the same reasons as other migrants: economic opportunity and reunification with family members. Other evidence, discussed below, suggests that some are being pushed out of their countries by widespread violence, which also was an important driver of Central American migration to the U.S. in the 1980s.

According to a 2011 Pew Research Center survey of U.S. Hispanic adults, Central American migrants – 83% of whom were born in the Northern Triangle – were less likely than other Latino migrants (46% vs. 58%) to cite economic opportunities as the main reason for relocating to the U.S. In addition, a smaller share of Central American immigrants cited family reasons for migrating (18% vs. 24% among other Hispanic immigrants).

Surveys of recently deported Northern Triangle migrants in their home countries 1 also found that work was a top motivator for their journey, according to a Pew Research Center analysis of 2016 data. Among Guatemalans deported from the U.S., 91% cited work as a main reason for coming, as did 96% of Hondurans deported from the U.S. and 97% of deported Salvadorans. Surveys of Northern Triangle migrants who were apprehended in Mexico while on the way to the U.S., then deported, also found that nearly all said they were moving to find work.

Violence may also play a role in immigrants’ motivations to migrate north

However, the same 2011 Pew Research Center survey that found economic opportunity was the top reason for Central American immigrants to come to the U.S. indicated that violence in Central America is a factor as well. Central Americans were more likely than other Latino migrants to cite conflict or persecution as a reason they left – 13% said that was the main reason they came to the U.S., compared with 4% of other Hispanic migrants, according to the National Survey of Latinos.

A 2014 U.S. Department of Homeland Security document cited poverty and violence in Northern Triangle nations as forces that motivated unaccompanied children who were being apprehended at the border in large numbers. The document, which was obtained by Pew Research Center, cited rural poverty in Guatemala and “extremely violent” conditions in El Salvador and Honduras. At a conference on Northern Triangle issues this year, U.S. Vice President Mike Pence spoke of “vicious gangs and vast criminal organizations that drive illegal immigration and carry illegal drugs northward on their journey to the United States.”

At the time of the 2014 DHS report, Honduras had the world’s highest murder rate – 74.6 homicides per 100,000 residents that year. El Salvador ranked second, with 64.2. Guatemala was ninth, at 31.2. In 2016, El Salvador had an even higher homicide rate than Honduras, 91.2 per 100,000 people. The Honduras rate was 59.1 and Guatemala’s was 23.7.

Northern Triangle nations also are among the poorest in Latin America. In 2014, some had relatively high shares of people living on less than $2 a day – 17% of Hondurans, 10% of Guatemalans and 3% of Salvadorans, according to World Bank data.

A 2013 Pew Research Center survey in El Salvador found that high shares of people living there – 90% or more – said crime, illegal drugs and gang violence were very big problems in their country. Half (51%) said they were afraid to walk alone at night within a kil0meter of their home.

The same survey also found that most Salvadorans not only knew someone already living in the U.S., but also wanted to move to the U.S. themselves. Nearly six-in-ten (58%) said they would move there if they could, including 28% who would move without authorization. Two-thirds of Salvadorans (67%) said they had friends or relatives who lived in the U.S. Most said people who move to the U.S. have a better life (64%) than those in their country.

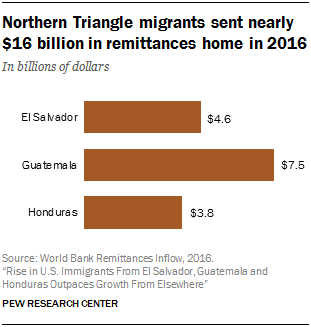

Remittances and the Northern Triangle

The Pew Research Center survey of Salvadorans in 2013 found that 84% said it is good for El Salvador that many of its citizens live in the U.S.

One reason for that might be the money they send home: According to a Pew Research Center analysis of World Bank data, Guatemala, El Salvador and Honduras were among the top 10 estimated remittance-receiving nations from immigrants in the U.S. in 2015.

The money that immigrants send home to Northern Triangle nations has grown substantially in recent years, except for a one-year dip in 2009, the final year of the U.S. recession. In 2016, according to World Bank estimates, remittances to the three nations totaled $15.9 billion, of which most came from the U.S. Those remittances were the equivalent of about 17% of the total economic output (as measured by gross domestic product) in El Salvador, 11% in Guatemala and 18% in Honduras in 2016.

Guatemalan immigrants around the world sent home $7.5 billion in remittances in 2016, while Salvadorans sent $4.6 billion and Hondurans $3.9 billion, according to World Bank data. The vast majority of the money came from immigrants in the U.S.

Guatemalan immigrants around the world sent home $7.5 billion in remittances in 2016, while Salvadorans sent $4.6 billion and Hondurans $3.9 billion, according to World Bank data. The vast majority of the money came from immigrants in the U.S.

The rise in remittances to Northern Triangle nations diverged from a decline in overall remittances to developing nations in 2016. A World Bank brief about global remittance trends, published in October, noted that money sent home by Northern Triangle and Mexican migrants went up despite an increase in deportations from the U.S. The increase in remittances “is in part due to possible changes in migration policies. Migrants are sending their savings back home in case they must return.”

The World Bank brief also stated that remittances may continue to rise because the tighter U.S. labor market could be driving employment, especially in the construction industry. Immigrants are overrepresented in the U.S. construction industry: They were 17% of the total workforce in 2014, but 24% of the construction workforce.

As these immigrant populations have gone up, Northern Triangle governments have expanded their outreach to their nationals in the U.S. The Guatemalan government, for example, opened two new consulates this year, in Raleigh, North Carolina, and in Oklahoma City. El Salvador opened a consulate in McAllen, Texas, in 2014 and another one in Aurora, Colorado, earlier this year.

This report is based largely on Pew Research Center analysis of U.S. Census Bureau data. Figures have been adjusted for undercount, so findings differ from official published numbers, but the trends and patterns are similar for both.

Central America includes Belize, Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua and Panama. The Northern Triangle includes El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras.

Origin refers to the heritage, nationality, lineage or country of birth of the person or the person’s parents or ancestors before arriving in the United States. U.S.-born residents reporting origins in El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Central America or Mexico are considered to be of Hispanic origin; almost all immigrants born in those countries say they are of Hispanic origin.

Foreign born refers to an individual who is not a U.S. citizen at birth — who, in other words, is born outside the U.S., Puerto Rico or other U.S. territories and whose parents are not U.S. citizens. The terms “foreign born” and “immigrant” are used interchangeably. Immigrants are identified by birth country, not origin, so “Salvadoran immigrants” refer only to those born in El Salvador.

U.S. born refers to an individual who is a U.S. citizen at birth, including people born in the United States, Puerto Rico or other U.S. territories, as well as those born elsewhere to at least one parent who is a U.S. citizen.

The lawful immigrant population is defined as naturalized U.S. citizens; people granted lawful permanent residence (previously known as legal permanent residence); those granted asylum; people admitted as refugees; and people admitted under a set of specific authorized temporary statuses for longer-term residence and work.

Unauthorized immigrants are all foreign-born noncitizens residing in the U.S. who are not lawful immigrants, as defined above. These definitions reflect standard and customary usage by the U.S. Department of Homeland Security and academic researchers. The vast majority of unauthorized immigrants entered the country without valid documents or arrived with valid visas but stayed past their visa expiration date or otherwise violated the terms of their admission. Some who entered as unauthorized immigrants or violated terms of admission have obtained work authorization by applying for adjustment to lawful permanent status, obtaining Temporary Protected Status (TPS) and/or receiving Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) status. This “quasi-lawful” group could account for as much as about 10% of the U.S. unauthorized immigrant population. Many could also revert to unauthorized status.