The most common form of cross-border exchange is communication. And among the different forms of communication, telephone calls are by far the most prevalent. Three-quarters of foreign-born Hispanics call someone in their native land at least occasionally, and two-thirds do so at least once a month. About 41% call at least once a week, with about 20% calling more than once a week.

The most common form of cross-border exchange is communication. And among the different forms of communication, telephone calls are by far the most prevalent. Three-quarters of foreign-born Hispanics call someone in their native land at least occasionally, and two-thirds do so at least once a month. About 41% call at least once a week, with about 20% calling more than once a week.

Although telephone calls are relatively inexpensive and widely accessible, putting an increasing proportion of family and friends within reach, not every Latino immigrant makes even the occasional call. Almost one-in-four Hispanic immigrants say that they never call (5%), almost never call (14%) or that they have no family or friends in their country of origin to call (4%).

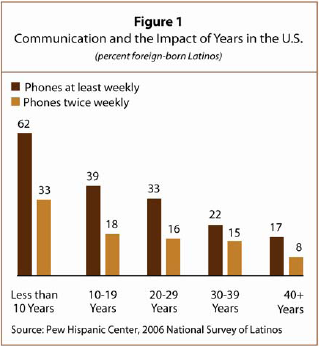

The extent of calling declines according to the amount of time an immigrant has spent in the U.S. Among the newest arrivals, almost two-thirds call at least once a week (Figure 1). But among those in the U.S. for at least a decade, the proportion falls to one-third and it drops further, to one-fifth, among those living in the country for 30 years or more. While the overall pattern is of declining activity, it is notable that a substantial minority of Latino immigrants who have lived in the U.S. for many years continues to make frequent calls to friends and relatives in their native land.

Differences by country of origin also vary widely, sometimes due more to politics than to personal relationships. Almost 60% of immigrants from the Dominican Republic make calls at least weekly. Meanwhile, with all forms of contact between people in the U.S. and those in another Caribbean island nation, Cuba, being restricted to some extent or another by the hostile relationship between the two nations’ governments (see box on page 6), Cubans have the lowest levels of weekly telephone contact (9%).

Another pattern is evident among Mexicans. More than one-third are in frequent contact, calling Mexico at least once a week, yet more than a quarter say they call rarely, if ever. As shall be seen, among Mexicans that pattern extends to other cross-border activities. In each, a significant minority displays few or no ties to Mexico.

Only 15% of Latino immigrants report using email to contact friends and family in their native lands. To a large extent, email communication is affected by access to computers. Only a third of Hispanic immigrants report using a computer on even an occasional basis, compared with three-quarters of U.S.-born Hispanics.

Among Latino immigrants who do not have access to a computer at home or at work, only 3% report having email contact with home country relatives or friends. By comparison, roughly a third of immigrants who have access at home or on the job say they have email contact. Dominicans again show strong ties to their home country, with 27% reporting that they send emails. Colombians, however, are the clear leaders, with almost half saying they use email to communicate with home country friends and relatives.

Travel

A trip back to the country of origin costs far more than a phone call or an email. Nevertheless, it is one of the two most common forms of maintaining a connection with the home country. In a sense, such travel best illustrates the ways in which U.S. and home country ties are mutually compatible and not mutually exclusive.

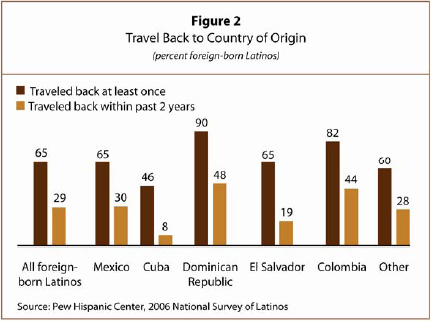

Since most Latino immigrants come from countries that are relatively close to the U.S., regular visits to their native lands would be expected. And that is indeed the case (Figure 2). Two-thirds (65%) report having made at least one trip back since they have been living in the U.S. Nearly half of those who have traveled back—29% of all Hispanic immigrants—have made a trip in the past two years.

But that still leaves a significant minority, about a third of immigrant Latinos, who do not report any travel to their native land (27% say they have never traveled). Recent arrivals account for most of the immigrants who have never traveled back or have not done so recently. Of those who have been in the U.S. for 20 to 29 years and thus have had greater opportunity to make a trip, nearly all (90%) have returned to their native land at least once, compared with less than half (45%) of those in the country for 10 years or less. Among those with longer periods of residence, travel to the native land is also an increasingly common experience: Latino immigrants who have been in the U.S. for 20 to 29 years, for example, are more than twice as likely to have traveled to their home country in the past two years than those who have been living in the U.S. 10 years or less (48% versus 21%).

Travel is somewhat less common among the longest-established residents, but that may reflect the distinctive experience of Cubans, who are disproportionately represented among respondents who have lived in the U.S. for 30-plus years. Taking into account both travel and communication, relatively few have severed contact. Of all respondents, about 16% report neither calling family nor friends in their native country nor traveling within the prior five years.

Both in frequency and prevalence, travel can vary significantly across the major national origin groups (Figure 2). At the two ends of the spectrum are Dominicans and Cubans. Almost all Dominicans (90%) report having traveled to their native land at least once. By contrast, just under half of Cubans—who face legal restrictions on travel to Cuba—report having gone to Cuba at least once (see box). How recently the travel took place also distinguishes the two groups. About 48% of Dominicans report having returned to their country of origin within the prior two years, as opposed to 8% of Cubans who faced a period of tightened restrictions on family travel to Cuba. Reflecting the circumstances of their migration, 45% of Cubans say they have never traveled to their native land, by far the largest share for any national origin group.

Despite their geographical proximity, Mexican immigrants do not travel to their country of origin more than other Latino immigrants, leaving aside Dominicans and Cubans with their distinctive profiles. For example, 65% of Mexicans say they traveled back at least once, including 30% in the past two years. Those rates are below the travel rates among Colombians (82% and 44% respectively) and similar to the rates among other Latino immigrants (60% and 28%). About half of all Mexican immigrants are here without authorization and thus face limits on their ability to leave and re-enter the country.

Restrictions on Transnational Contacts with Cuba

In order to put economic pressure on the government of Fidel Castro, the United States first imposed an embargo on Cuba in 1962 (Cuban Assets Control Regulations – CACR) and since then has enacted a variety of laws and regulations restricting travel, commerce, financial transactions and other forms of interaction. The following policies currently limit transnational activities by Cubans in the United States:

Communication

While Cuban telecommunication and Internet infrastructure lags behind that of the Caribbean region and much of the world, there are no specific policies prohibiting phone calls or email from the U.S. to the island. However, the U.S. Postal Service does not accept letter post and parcel post packages of merchandise to Cuba.

Travel

The embargo regulations do not ban travel itself, but place restrictions on any financial transactions related to travel to Cuba, which effectively result in a travel ban. Under the Bush administration, the travel regulations have been tightened significantly, with additional restrictions on family visits, educational travel and travel for those involved in amateur and semi-professional international sports federation competitions. Family visits are now restricted to one trip every three years under a specific license to visit only immediate family (grandparents, grandchildren, parents, siblings, spouses and children) for a period not to exceed 14 days.

Remittances

Since June 2004, U.S. Treasury Department regulations have limited remittances to members of the sender’s immediate family and to $300 per household in any consecutive three-month period, provided that no member of the household is a prohibited official of the government of Cuba or a prohibited member of the Cuban Communist Party.

Sources:

U.S. Department of Treasury, Office of Foreign Assets Control, An Overview of the Cuban Assets Control Regulations Title 31 Part 515 of the U.S. Code of Federal Regulations.

Sullivan, Mark. “Cuba: U.S. Restrictions on Travel and Remittances.” August 2006 CRS Report for Congress.

Citizens versus non-citizens

Generally speaking, immigrants who are legally authorized to reside in the U.S. can seek to become U.S. citizens after they have lived in the country for five years. In recent years, the share of eligible Hispanic immigrants seeking citizenship has been on the rise. (See Growing Share of Immigrants Choosing Naturalization, Pew Hispanic Center, March 28, 2007.) How does citizenship affect cross-border activities? The findings from this survey are mixed.

Generally speaking, immigrants who are legally authorized to reside in the U.S. can seek to become U.S. citizens after they have lived in the country for five years. In recent years, the share of eligible Hispanic immigrants seeking citizenship has been on the rise. (See Growing Share of Immigrants Choosing Naturalization, Pew Hispanic Center, March 28, 2007.) How does citizenship affect cross-border activities? The findings from this survey are mixed.

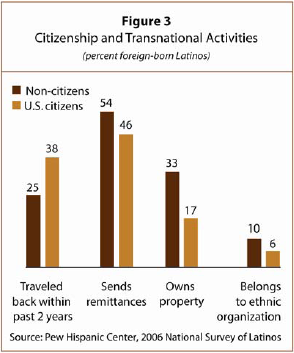

A larger share of non-citizens phones their native land at least once a week than do immigrants who have become U.S. citizens (46% versus 31%). Citizens are also less likely than non-naturalized respondents to send home money home, though a substantial minority (46%) does (Figure 3). Naturalized citizens were half as likely as their non-naturalized counterparts to own property in their country of birth, while they were twice as likely to own the house in which they lived in the U.S.

However, when it comes to travel, about 81% of Latino immigrants who are U.S. citizens report having traveled to their country of origin at least once, compared with 57% of those who are not naturalized. Citizens are also more likely than their non-naturalized counterparts to have traveled to their home country within the past two years—even though the citizens on average have been living in the U.S. for a much longer period of time. This may reflect the fact that citizens can leave and reenter the country as they please. A substantial share of foreign-born Latinos who are not citizens are living in the U.S. without authorization. For them, reentering the U.S. can be a difficult and expensive proposition.