Most Hispanics are affiliated with the same religious faith they have always practiced, but an important minority, almost one-in-five Latinos, say they have either changed their affiliation from one religion to another or have ceased identifying with any religion at all. The study offers a detailed look at the motivations and attitudes of Latinos who leave one faith to join another or to become secular.

What drives conversion to a new religion? Often it is a response to a very specific spiritual need. By an overwhelming margin, converts say they sought a new religion because they wanted to be closer to God. Sometimes the conversion seems to be rooted in the worship experience; one-in-three evangelical converts from Catholicism say the lack of excitement at Catholic Masses was a factor in their decision to leave the church.

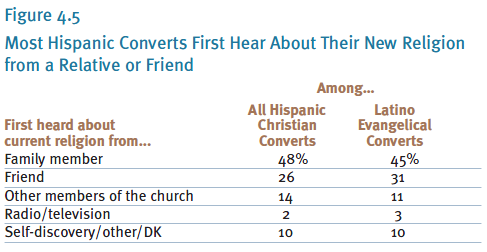

Family members and acquaintances emerge as important factors in the process of conversion; they are the ones who frequently introduce the new religion. That personal relationship is far more important in conversion than is the influence of the media or personal contacts with other members of the church.

Very few Hispanics who converted from Catholicism to a new religion say they did so because they were dissatisfied with the church’s positions on certain issues. Nearly half (47%) of Hispanic Catholics disapprove of the church’s position on divorce, for example, but only 7% of those who have left Catholicism for another religion say it was a reason for their conversion.

To understand the scope and methods of conversion, it is also useful to examine how Hispanics view the Catholic Church. Latinos, overall, hold mixed opinions. Many Hispanics are at odds with the church’s teachings on divorce and whether women and married men should be ordained as priests. And while most Latinos say the typical Mass is lively and exciting, many hold the opposite view. At the same time, the Catholic Church is perceived as welcoming to immigrants. And even though Hispanics are split on whether women should be ordained, most also view the church as having equal respect for men and women.

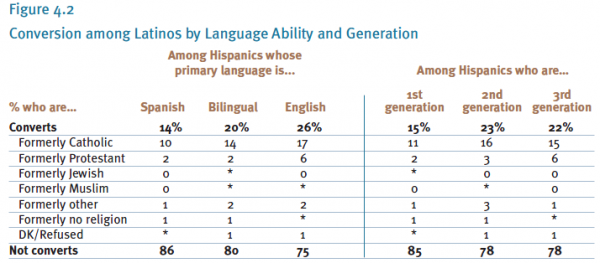

An analysis of the study’s findings suggests that changes in Latinos’ religious affiliation, particularly from one religion to another, may be associated with the complex processes of migration and assimilation. Conversion is higher among the native born than the foreign born, for example, and it is also higher among English-speaking Latinos than it is among Spanish speakers.

Conversion and secularization

Conversion flows

The vast majority of Latinos (82%) give no indication of ever having changed their religious affiliation. However, almost one-in-five (18%) Latinos say they have either converted from one religion to another or to no religion at all. Given that most Hispanics are Catholic, a large majority of converts (70%) are former Catholics.

Conversions are a key ingredient in the development of evangelicalism among Hispanics. Half of Hispanic evangelicals (51%) are converts, and more than four-fifths of them (43% of Hispanic evangelicals overall) are former Catholics. By contrast, 2006 Pew Forum Global Survey of Pentecostals found that 44% of white evangelicals in the U.S. have changed their religion, and fewer than one-in-ten of them are former Catholics.

Almost two-thirds of Latino seculars (65%) indicate that they had practiced some religious faith at one time in their lives and nearly four-in-ten (39%) of them are former Catholics. The movement of converts to the Catholic Church is much smaller, with only 2% of Latino Catholics saying they previously practiced another religion.

Immigration and assimilation

Though it is impossible to determine the precise extent to which conversion is a product of assimilation, it does appear that migrating to the United States, learning English and undergoing the other changes that occur with exposure to American ways do seem to be somewhat associated with changes in religious affiliation. Conversion is more prevalent among native-born Latinos than it is among foreign-born Latinos, for instance. However, there is little difference in the share of converts among the second and third generations (23% vs. 22%, respectively).

In line with the findings on nativity, 26% of all Latinos whose primary language is English converted, compared with 20% of those who are bilingual and 14% of those whose primary language is Spanish. That association persists even when controlling for other factors, such as gender, generation and education.

‘Converts’ to Secularism

More than one-in-four converts (28%) report moving away from religion altogether. As is the case with converts in general, most Latinos who have left religion were previously Catholic (39% of Latino seculars overall). Less than half as many Latino seculars (15%) are former Protestants.

Perhaps the most striking aspect of this segment of the population is the high proportion who are male, 66%, compared with 34% who are female.

On average, converts to secularism are relatively well-off. About 20% have graduated from college, compared with 10% among all Hispanics. Many also have relatively high incomes. Almost a third earn $50,000 or more annually, compared with 17% among all Hispanics. More than half are native born (54%) and more than two-thirds (68%) say they are English dominant or bilingual.

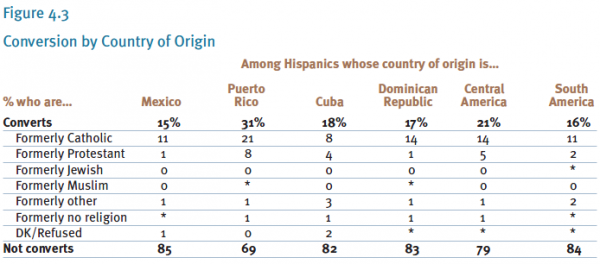

Country of origin

The prevalence of conversion varies little by country of origin, with one noteworthy exception. Almost one-in-three (31%) Puerto Ricans are converts. An analysis of the survey results shows that even when controlling for several demographic and socioeconomic factors, Puerto Ricans are significantly more likely to convert than are other Hispanics.

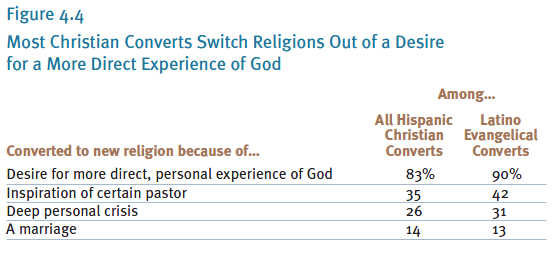

Reasons for converting to another religion

The desire for a more direct, personal experience with God is one factor that drives Hispanics to convert from one religion to another. More than eight-in-ten Latino converts cite this as a reason for adopting a new faith. That belief is particularly strong among those who have become evangelicals, nine-in-ten (90%) of whom say it was that spiritual search that drove their conversion.

About one-in-three Latinos (35%) who have changed affiliation to a new religion say the influence of a certain pastor was a factor in their conversion. About one-in-four (26%) attribute their conversion at least in part to a deep personal crisis, and 14% say they converted as a result of a marriage. Such motivations are not mutually exclusive, of course, and the survey does not attempt to rank them by intensity.

Among Hispanics who are third generation and higher, 40% cite the influence of a pastor, compared with 27% in the first generation. Among converts whose primary language is English, 44% attribute their conversion to the influence of a particular pastor, compared with 25% of Spanish speakers.

Sources of information about a new religion

Converts to Christian denominations were asked how they first heard about their new faith. The answers, while not conclusive, nevertheless provide a tantalizing glimpse into the origins of this complicated process.

Most Hispanic Christian converts say they first heard about what was to become their new religion from relatives (48%) or friends (26%). Only 14% say they first heard about their new religion from members of the church to which they converted. Only 2% say they first heard about their new religion from radio or television.

Views of the Catholic Church among converts

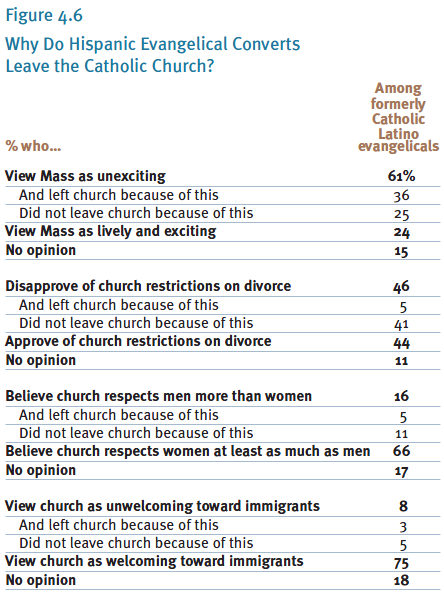

The high percentage of Latino evangelicals who converted — and the fact that most of them are former Catholics — makes them a particularly interesting segment of the Hispanic population. The survey posed four questions to evangelical converts, probing for possible reasons for their leaving the Catholic Church. While many express negative views of some of the teachings and practices of the church they left behind, those opinions do not emerge as widespread motives for converting.

The largest share of negative views came in response to a question about the Catholic Mass. A majority of Latino evangelical converts from Catholicism (61%) say they do not find the typical Catholic Mass to be lively or exciting, and about one-in-three (36%) cite that as a factor in their conversion. Among Latinos who identify as Catholic, on the other hand, 71% say the typical Mass is lively and exciting; 22% disagree.

The church’s restriction on divorce does not weigh substantially on conversion overall. While many evangelical converts (46%) disapprove of the church’s restrictions on divorce, only 5% cite that as a reason for their conversion; 41% explicitly say they did not leave the church because of it. Latino Catholics themselves are similarly split on the church’s teachings on divorce (47% disapproving and 44% approving).

Two-thirds (66%) of Latino evangelical converts say the Catholic Church respects women at least as much as men, and three-in-four view the church as welcoming to immigrants. Neither of these issues is cited by many converts as a reason for leaving the church, and Latino Catholics express positive views on these matters by similar margins.

A slim majority of Hispanics believe that married men should be allowed to serve as Catholic priests, but Latino Catholics are much less likely to hold this point of view (44%) than are evangelicals (71%) or seculars (66%). The difference between Latino Catholics and evangelicals is smaller when it comes to the question of ordaining women; among both groups, less than half (44% among Catholics and 46% among evangelicals) agree that women should be allowed to serve as Catholic priests. This may reflect the fact that, like the Catholic Church, many evangelical denominations do not ordain women. Latino seculars are much more willing than either group to support the ordination of women (65%).

Hispanic Catholics are much more supportive of the church’s position on these issues than are American Catholics as a whole. For example, a 2002 Princeton Survey Research Associates poll conducted for Newsweek found that among all non-Hispanic Catholics, 65% said it would be a good thing to allow women to be ordained as priests and 76% said it would be good to allow married men to become priests.

Although they are split on the church’s prohibition on women priests, a large majority of Hispanics reject the idea that the church respects the contributions of women less than it does the contributions of men.

Most Hispanics (81%) say that the Catholic Church is at least somewhat welcoming to new immigrants, with more than half (56%) describing it as very welcoming. Smaller shares of evangelicals (50%) and seculars (46%) than Catholics (60%) view the church as very welcoming to new immigrants.

The study finds no differences between immigrant and native-born Hispanics in their views on the church’s openness to new immigrants. Among immigrants, second-generation Hispanics and those whose families have been in the U.S. for three generations or more, 80% or more say the church is at least somewhat welcoming to new immigrants. Similarly, there are only small differences on this question among Hispanics of different countries of origins.