The new South counties selected for analysis in this report were classified into three groups based on their economic characteristics. The key factors were the counties’ principal industrial sources of income and employment in 1990 and 2000. Consideration was also given to patterns of growth in income and employment across industries in the 1990s. Did an industry emerge during the decade to become a leading source of income or employment in a county? Some weight was also given to a county’s population and geographic location. For instance, is a county part of a large, diverse and heavily populated metropolitan area? Such a county, even if it appeared specialized in an industry, would be part of larger and more diverse economy. The application of these criteria is, by necessity, judgmental. It is possible that some counties may have been classified elsewhere based on alternative criteria or if different weights had been given to the same criteria.

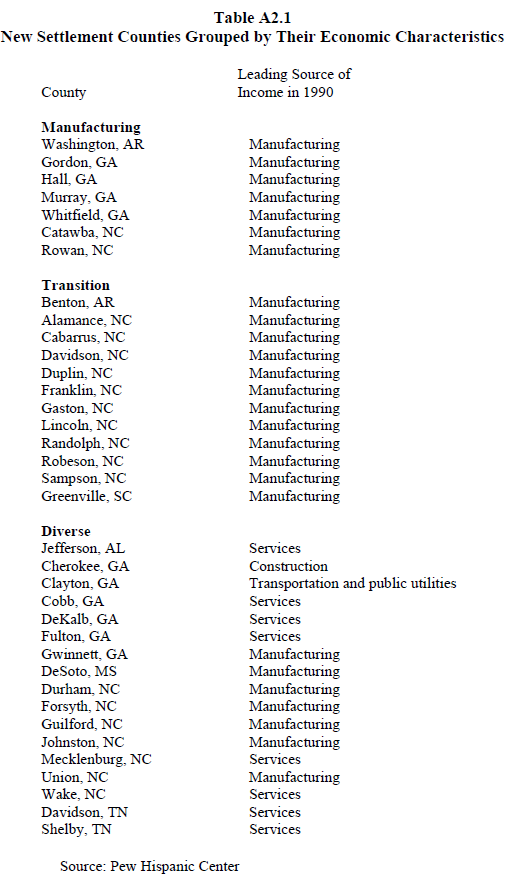

Table A2.1 shows the composition of the three groups of counties. The Manufacturing group consists of seven counties—four in Georgia, two in North Carolina and one in Arkansas. Based on income generation, two of these counties (Washington in Arkansas and Hall in Georgia) counted food and kindred products as their single most important manufacturing industry in 1990. Gordon, Murray and Whitfield counties in Georgia rely on textile products, while Catawba, N.C., depends on the furniture and fixtures industry. Rowan, N.C., has a more diverse manufacturing base and actually made a transition away from non-durable goods manufacturing to durable goods manufacturing in the 1990s.

The Transition counties are almost all in North Carolina. The exceptions are Benton in Arkansas and Greenville in South Carolina. The manufacturing industry was the leading source of income and employment in Benton in 1990 but was supplanted by retail trade (led by Wal- Mart) by 2000. In Greenville, the manufacturing industry is losing its leading position to the services industry, with especially strong growth in business services. The counties in North Carolina include two rural counties (Duplin and Sampson) where food and kindred products are important. The remaining counties (Alamance, Cabarrus, Davidson, Franklin, Gaston, Randolph and Robeson) were primarily reliant on the furniture and fixtures and textile industries in 1990. The common denominator in these counties is a slippage in manufacturing income or employment and the emergence of other leading sectors.13 For example, the manufacturing sector in Gaston County provided twice as many jobs as the services sector in 1990 but the two sectors were in a virtual tie by 2000 as the former shed jobs and the latter added them.

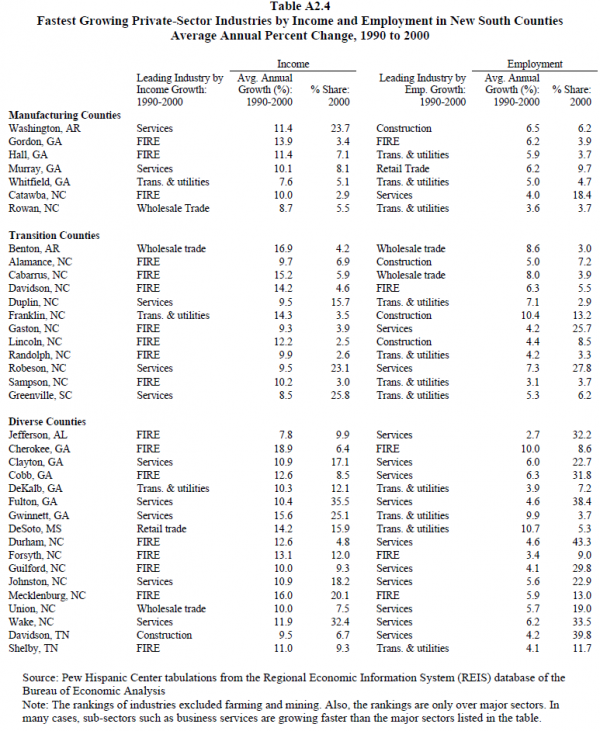

The final group of counties—the Diverse group—draws from all six states except South Carolina. This group encompasses large metropolitan areas including those around Atlanta, Charlotte, Nashville, Memphis and Birmingham. Many of these counties are dependent on services as a leading source of income. Cherokee County, Ga., draws a high share of income from construction and Clayton, Ga., is very dependent on transportation and public utilities. Durham County, N.C., has a sizable manufacturing base but the services sector is also a leading source of income and actually provided more than twice as much employment as manufacturing in this county in 2000. Mecklenburg, N.C., is home to the core of the Charlotte-Gastonia metropolitan area and the fire, insurance and real estate industry nearly doubled the number of jobs it provided in this county between 1990 and 2000. The share of income provided by FIRE in Mecklenburg also doubled in this decade. Growth in the counties located around Atlanta (Cherokee, Cobb, Clayton, DeKalb, Fulton and Gwinnett) came from a number of industries ranging from construction to business services to FIRE.

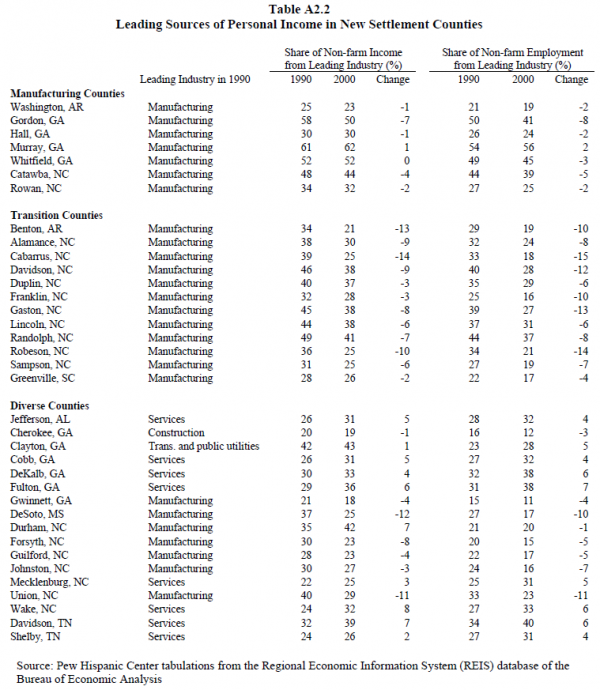

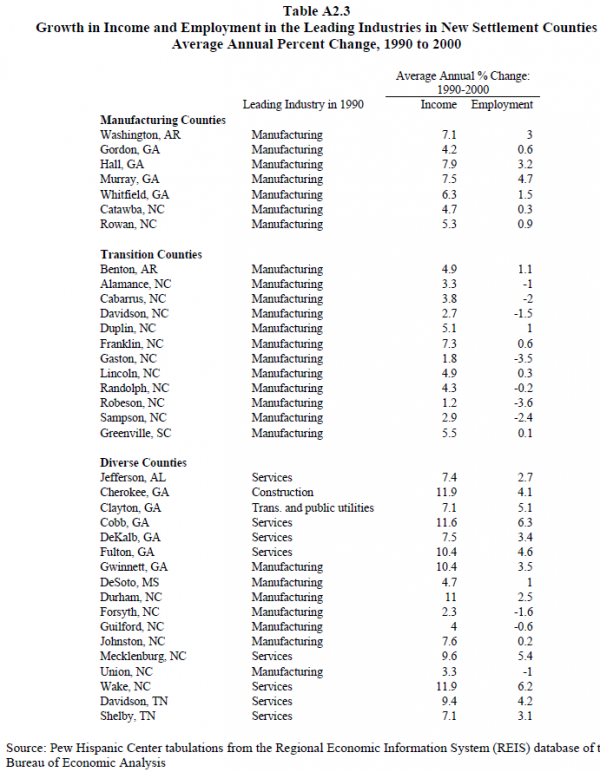

The next two tables in this appendix demonstrate how the selection criteria were applied to place individual counties into one of three groups. Table A2.2 shows the leading sources of non-farm income in the various counties in 1990. Four counties in the Manufacturing group— Gordon, Murray and Whitfield in Georgia and Catawba in North Carolina—derived nearly 50 percent or more of their income and employment in 1990 from manufacturing alone. The shares of income and employment contributed by manufacturing in these counties did not change by much between 1990 and 2000. Moreover, all Manufacturing counties added manufacturing jobs in the 1990s (Table A2.3). That was a key factor in including Washington County, Ark., and Hall County, Ga., in this group. Both counties added manufacturing jobs at a rate of at least 3 percent per year between 1990 and 2000. Manufacturing in Rowan, N.C., may not appear to play as strong a role as in some counties classified into other groups. However, the contribution of manufacturing to the economy in Rowan barely diminished in the 1990s as it made a successful transition from non-durable goods to durable goods industries.

The second group of counties—Transition—captures counties that had a strong manufacturing base in 1990 but that made a notable move in the direction of other industries over the decade. An example is Benton County, Ark., where the share of income and employment coming from manufacturing slipped by over 10 percentage points between 1990 and 2000. The rise of Wal-Mart made retail trade the leading industry in this county by 2000. Notable declines in the shares of income and/or employment from manufacturing are also apparent in Alamance, Cabarrus, Davidson, Franklin, Gaston, Randolph and Robeson counties in North Carolina (Table A2.2). The emerging industries in these counties include FIRE, service and construction (Table A2.4). Manufacturing employment in Greenville County, S.C., remained at a standstill in the 1990s and services emerged to occupy a leading position by 2000. Duplin and Sampson in North Carolina are neighboring rural counties and census data for them are not available individually. In light of a strong trend in the direction of services in Sampson both counties are included in the Transition category.

The Diverse counties are typically heavily populated and many draw considerable income and employment from sectors other than manufacturing. For example, transportation and public utilities contributed over 40 percent of income and 28 percent of employment in Clayton County, Ga., in 2000. DeSoto, Miss., and Union, N.C., are examples of counties that had a significant manufacturing presence in 1990 but that diversified strongly by 2000 (into construction, services and retail trade in the case of DeSoto and into construction in the case of Union.) Durham County, N.C., is an interesting case in that the contribution of manufacturing to income actually increased between 1990 and 2000. However, the services industry employed 43 percent of workers in Durham County in 2000 (Table A2.4) in comparison with only 20 percent in manufacturing. Thus it is placed in the Diverse group. The inclusion of the other counties in this category is largely self-evident.

As noted above, census data for some counties listed in Table A2.1 are not separately available. In the case of Gordon, Murray and Whitfield counties in Georgia, this is not problematic: All three naturally fall into the Manufacturing category. A pair of counties in the Transition category—Lincoln and Gaston in North Carolina—are also grouped in the census 52 data. In the case of Franklin and Johnston counties in North Carolina, however, the former is placed in the Transition group and the latter in the Diverse category even though census data for these two counties are only available in combination. Where necessary, those data were included twice in the analysis for this paper, once in computing statistics for the Transition group and again in characterizing the Diverse counties.