This report presents a range of material on the unauthorized migrant population resident in the United States.1 Several major aspects of unauthorized migrants in the U.S. receive attention:

Demographic Aspects:

- How many immigrants are coming to the U.S.;

- How many are already in the U.S.; What share are they of the U.S. immigrant population;

- Where do they come from;

- Where do they live in the U.S.;

- What legal statuses do immigrants have;

- What kinds of families do they have;

- How old are they?;

Socioeconomic Characteristics:

- What are the unauthorized migrants’ levels of education;

- What occupations have the most unauthorized migrants;

- How do their incomes compare with other groups;

- What are their poverty levels;

- How many do not have health insurance?

Finally, the briefing pulls together information from Mexico and the United States to describe trends in the growth of the Mexican-born population of the United States. Population projections for the number of Mexicans in the U.S. through 2050 are presented.

About the Paper

This report was developed as a briefing paper for the Independent Task Force on Immigration and America’s Future, co-chaired by former Senator Spencer Abraham (RMI) and former Congressman Lee Hamilton (D-IN). The bipartisan task force has been convened by the Migration Policy Institute in partnership with the Manhattan Institute and the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars. The report on the unauthorized population was presented to the task force by the Pew Hispanic Center, a nonpartisan research group in Washington DC, to provide a factual basis for its discussions. The Pew Hispanic Center, which does not engage in issue advocacy, is not participating in the task force’s deliberations or its policy recommendations. The report draws on both new research and previous work done by the author at the Pew Hispanic Center and the Urban Institute where he worked until January 2005.

This report uses the term “unauthorized migrant” to mean a person who resides in the United States, but who is not a U.S. citizen, has not been admitted for permanent residence, and is not in a set of specific authorized temporary statuses permitting longer-term residence and work. (See Passel, Van Hook, and Bean 2004 for further discussion.) Various labels have been applied to this group of unauthorized migrants, including “undocumented immigrants,” “illegals,” “illegal aliens,” and “illegal immigrants.” The term “unauthorized migrant” best encompasses the population in our data because many migrants now enter the country or work using counterfeit documents and thus are not really “undocumented,” in the sense that they have documents, but not completely legal documents. While many will stay permanently in the United States, unauthorized migrants are more likely to leave the country than other groups (Van Hook, Passel, Zhang, and Bean 2004). Thus, we use “migrant” rather than “immigrant” to highlight this distinction.

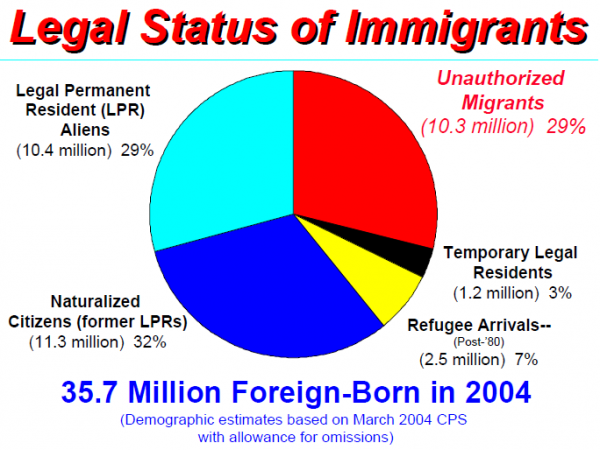

The chart sub-divides the foreign-born population in 2004 according to estimates of legal status.

The chart sub-divides the foreign-born population in 2004 according to estimates of legal status.

In 2004, naturalized citizens represent just under one-third of the foreign-born population at 11.3 million or 32% of the 35.7 million estimated total. Legal permanent resident aliens (LPRs or “legal immigrants”) who have not yet become citizens represent about 10.4 million or about 29% of all immigrants living in the country. A substantial share of the foreign-born population (just over 10 million or 29%) is unauthorized (either entering clandestinely without inspection, with fraudulent documents, or overstaying visas), and a smaller share (2.5 million or 7%) is made up of refugees2 (immigrants who fled persecution). Another 3-5% of foreign-born residents are “legal nonimmigrants,” temporary visitors such as students and temporary workers.

The unauthorized population has been steadily increasing in size (and possibly by large increments since the last half of the 1990s). Similarly, the naturalized citizen population has grown rapidly in recent years as increasing numbers of legal immigrants have become eligible and taken advantage of the opportunity to naturalize. The LPR alien population, on the other hand, actually decreased for several years as the number who have naturalized (or left the U.S. or died) exceeded the number being admitted.

Source: Based on Pew Hispanic Center estimates derived principally from the March 2004 Current Population Survey (CPS) and Census 2000 (Passel 2005). (See also Passel et al. 2004; Passel 2002, 2003.) Neither dataset, however, includes direct information on unauthorized status or any legal status, other than naturalization. Our estimates also draw on data from the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS), the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), and information about countries of birth, time spent in the U.S., and occupation (Passel and Clark 1998; Passel, Van Hook, and Bean 2005.) Note that these estimates include an allowance for immigrants not included in the CPS.

This chart shows estimates of the unauthorized migrant population as of March 2004 subdivided the country/region of birth.

This chart shows estimates of the unauthorized migrant population as of March 2004 subdivided the country/region of birth.

There are about 10.3 million unauthorized migrants estimated to be living in the United States as of March 2004. Of these, about 5.9 million or 57% are from Mexico. The rest of Latin America (mainly Central America) accounts for another 2.5 million or about one-quarter of the total. Asia, at about 1.0 million, represents 9%. Europe and Canada account for 6% and Africa and Other about 4%.

The estimates presented in this chart are derived by Passel (2005) using residual techniques applied to the March 2004 CPS. Note that the methodology adjusts for legal immigrants and unauthorized migrants not included in the March 2004 CPS; approximately 1 million unauthorized migrants are estimated to be omitted from the CPS.

Source: Based on Passel 2005 using methods described in Passel et al. 2004. See also pages 3, 7–9.

This chart shows estimates of the unauthorized migrant population as of March 2004 subdivided by when the migrants arrived in the United States.

This chart shows estimates of the unauthorized migrant population as of March 2004 subdivided by when the migrants arrived in the United States.

About 30% of the unauthorized population in 2004 or 3.1 million persons arrived in the 4+ years since 2000. In the 5 years before that, 3.6 million arrived. Thus, about two-thirds of unauthorized migrants have been in the country less than 10 years.

Note that the average number of arrivals each year during any period is likely to have been larger than the annualized figures shown here because some of the arrivals will have left by 2004. Thus, the data presented here suggest that the annual unauthorized entries in the post-2000 period, while still extremely high, may have decreased somewhat from the period just before 2000.

It should also be emphasized that these estimates represent persons still in an unauthorized status as of March 2004. For example, many persons who arrived as unauthorized migrants during the 1980s acquired legal status through the Immigration Reform and Control Act of 1986 (IRCA) or other mechanisms in the more than one decade since they arrived. Thus, average annual arrivals of unauthorized migrants during the 1980s were undoubtedly higher than the figures shown here.

Source: Based on Passel 2005 using methods described in Passel et al. 2004.

The figures represent the population as of March 2004 subdivided by their legal status in 2004 and by the period when they arrived in the United States. There are a number of interesting relationships shown by these data:

The figures represent the population as of March 2004 subdivided by their legal status in 2004 and by the period when they arrived in the United States. There are a number of interesting relationships shown by these data:

- The number of legal immigrants arriving has not varied substantially over this period. (“Legal immigrants” here include LPRs, refugees, and asylees.)

- As in the previous chart, the vast majority of unauthorized migrant have arrived in the last 10 years.

- Since the mid-1990s, arrivals of unauthorized migrants have exceeded arrivals of legal immigrants.

- The data suggest the possibility of a slight decrease in both legal and unauthorized migrants since the late 1990s.

Note that the average number of arrivals each year during any period is likely to have been larger than the annualized figures shown here because some of the arrivals will have left by 2004. Thus, the data presented here suggest that the annual unauthorized entries in the post-2000 period, while still extremely high, may have decreased very slightly from the period just before 2000.

Source: Derived from data shown on page 5. Based on Passel 2005 using methods described in Passel et al. 2004.

This chart and the next two describe the methods used to estimate the size of the unauthorized migrant population. Although understanding the specific details of the methods is not essential, understanding the legal statuses represented by the estimates can be quite helpful in interpreting the results, especially in the context of alternative policy formulations.

This chart and the next two describe the methods used to estimate the size of the unauthorized migrant population. Although understanding the specific details of the methods is not essential, understanding the legal statuses represented by the estimates can be quite helpful in interpreting the results, especially in the context of alternative policy formulations.

The estimates of unauthorized migrants discussed here are derived using a variant of a basic “residual” method. In this method, an estimate of the legally-resident foreign-born population is first developed using data on admissions from INS (now Department of Homeland Security or DHS) as well as data on refugees admitted and asylum granted from various agencies. After allowing for legal temporary migrants (or “nonimmigrants” in the parlance of INS) and for legal immigrants missed in the Census or CPS, the initial estimate of the unauthorized population is derived by subtracting the estimated legal population from the Census or CPS figure for the total foreign-born population. This initial estimate of the number of unauthorized migrants counted is then inflated for omissions.

All calculations are done by country or region of birth, age, sex, period of arrival, and state or region of residence.

The residual method has been used for several decades to measure unauthorized migration to the U.S. Specifically, some of the first sound empirical estimates by Warren and Passel (1987, also Passel 1986) came from residual methodology applied to the 1980 Census. Variants of the method were used or discussed by the Census Bureau, the Panel on Immigration Statistics, the Bi-National (U.S.-Mexico) Study and the Commission on Immigration Reform, INS, and a number of other organizations and researchers.

In the residual method, the unauthorized population is defined, in part, by exclusion; that is, by which groups are included in the estimate of legal foreign-born population and which groups are omitted. In other words, the unauthorized population consists of persons and groups not included in the authorized population. This chart lists the groups included in our estimates of legal foreign-born residents:

In the residual method, the unauthorized population is defined, in part, by exclusion; that is, by which groups are included in the estimate of legal foreign-born population and which groups are omitted. In other words, the unauthorized population consists of persons and groups not included in the authorized population. This chart lists the groups included in our estimates of legal foreign-born residents:

- a. Refugees are counted in the year they arrive in the U.S., not when they get green cards;

- b. Asylum approvals, likewise, are included as legal when approved, not when they get green cards;

- c.-d. Cuban-Haitian and other entrants, Amerasians, and various groups of parolees are also included as legal when approved, not when they get green cards; for some, these dates are the same;

- e. Persons acquiring legal status under IRCA are included when they obtain their green cards;

- f. INS (or DHS) “New Arrivals”—i.e., persons getting green cards as they enter the U.S.—are counted in the year they arrive (unless they have already been counted in groups c.-d. to avoid double counting);

- g. Persons “adjusting” to LPR status—i.e., persons getting green cards who are already in a legal status in the U.S.—are counted in the year they get their green card (unless they have already been counted in groups a.-e. to avoid double counting);

- h. Census or CPS counts of persons arriving before 1980 are all assumed to be legal by 2000.

Note that the “year of arrival” for a legal immigrant may be different from the year they are included in the legal population. This year can be much earlier than the year of acquiring legal status, especially for IRCA legalizations (Group e.) and INS adjustments ( Group g.).

In addition, the particular variant of the method employed here includes estimates of some legal temporary visa categories as part of the legal population. The visa categories counted as legal include: A, F, G, H-1B, some H-2’s,some J’s, L, M, N, O, P, and R. (See Passel, Van Hook, and Bean 2004 and 2005.)

This chart displays some ways of describing unauthorized migrants in the residual-based estimates. First, virtually all of the unauthorized are either visa overstayers (that is, persons admitted on temporary visas who either stay beyond the expiration of their visas or otherwise violate their terms of admission) or EWIs (“entries without inspection” or clandestine entrants). Visa overstayers probably represent 25% to 40% of the unauthorized migrants.3

This chart displays some ways of describing unauthorized migrants in the residual-based estimates. First, virtually all of the unauthorized are either visa overstayers (that is, persons admitted on temporary visas who either stay beyond the expiration of their visas or otherwise violate their terms of admission) or EWIs (“entries without inspection” or clandestine entrants). Visa overstayers probably represent 25% to 40% of the unauthorized migrants.3

Another view of this population is to consider various administrative categories not included in the estimated legal foreign-born population described in the previous slides. Many such persons actually have EADs (or “Employment Authorization Documents”) issued by DHS and thus could be considered as “authorized” in some sense. Persons with Temporary Protected Status (TPS) and Extended Voluntary Departure (EVD) together with applicants for these statuses may account for 300,000-400,000 persons (DHS 2004). In addition, another 250,000 have applied for asylum but have not had their cases adjudicated. Although some individuals in these categories may eventually acquire green cards, many (perhaps most) will not.

Another large group not included in our estimate of legal residents but who have employment authorization and are not subject to deportation are persons in the legal immigration backlog. There are more than 600,000 persons in the U.S. who have applied for green cards but are waiting for them to be issued. In addition there perhaps another 100,000 persons who are immediate relatives or fiancées of legal residence waiting for their final papers. Most persons in these groups will eventually acquire green cards.

All told, there are probably about 1–1.5 million persons represented in our estimates of unauthorized residents who are known to DHS and have full legal statuses pending but are not yet fully legal.

A major demographic story of the 1990s is a broad increase in the unauthorized population. This chart portrays the growth trend in the unauthorized population while illustrating the uncertainty involved with the dotted bands of error and the alternative trend line at the end incorporating the results based on the 2000 Census and subsequent March CPSs through 2004. (Note that smooth lines should not be interpreted to mean that there are not annual fluctuations in growth. The lines merely connect the dates for which stock estimates are available.)

A major demographic story of the 1990s is a broad increase in the unauthorized population. This chart portrays the growth trend in the unauthorized population while illustrating the uncertainty involved with the dotted bands of error and the alternative trend line at the end incorporating the results based on the 2000 Census and subsequent March CPSs through 2004. (Note that smooth lines should not be interpreted to mean that there are not annual fluctuations in growth. The lines merely connect the dates for which stock estimates are available.)

Because of inherent uncertainties in the residual technique, the difference in successive annual estimates of the unauthorized population is not a valid measure of growth. However, it is possible to use differences taken over longer intervals to measure growth. Thus, the average annual change over the 2000-2004 period is about 485,000 or 10.3 million minus 8.4 million divided by 4. For the entire decade of the 1990s, growth averaged just about 500,000 per year. However, there are a number of data sources that point to substantially larger growth increments at the very end of the 1990s (and possibly at the end of the 1980s and the very early 1990s).

The apparent slowdown in growth after 1996 is probably not a real decline but is attributable to undercoverage in the data used to estimate unauthorized flows. Similarly, the apparent very rapid growth to 2000 may (or may not) be an accurate depiction of the trend but may reflect data anomalies in the CPSs of the late 1990s.

The decrease in size from 1986 to 1989 is caused by the IRCA legalizations that removed immigrants from the unauthorized population by granting them legal status, not by making them leave the country.

This chart shows estimates of the unauthorized migrant population for states averaged over three March CPSs, 2002–2004.

This chart shows estimates of the unauthorized migrant population for states averaged over three March CPSs, 2002–2004.

Almost two-thirds (68%) of the unauthorized population lives in just eight states: California (24%), Texas (14%), Florida (9%), New York (7%), Arizona (5%), Illinois (4%), New Jersey (4%), and North Carolina (3%). The appearance of Arizona and North Carolina on this list highlights another recent trend. In the past, the foreign-born population, both legal and unauthorized, was highly concentrated. But, since the mid-1990s, the most rapid growth in the immigrant population in general and the unauthorized population in particular has taken place in new settlement areas where the foreignborn had previously been a relatively small presence.

Source: Based on Passel 2005 using methods described in Passel et al. 2004. See also pages 3, 7–9. Estimates for CA, TX, FL, NY, IL, and NJ are “direct” in that they use components of population change—immigration, mortality, emigration, and internal migration. For other states, synthetic methods state-level figures on populations and are averages of the percentage unauthorized by country of birth and period of arrival. Because of instability and sampling variability in the state level figures, the estimates shown are averages for 2002–2004 except for AZ and NC. All estimates are approximate and rounded independently.

This chart shows the high degree of geographic diversification that occurred for the unauthorized population during the 1990s. In 1990, 45% of the unauthorized population, or about 1.6 million persons, lived in California; by 2004, the share had dropped to 24%. Note, however, that because of the sizeable growth in the unauthorized population, California still experienced substantial growth to about 2.4 million or growth of about 45%. Texas’ share increased while New York’s dropped significantly. In Florida, New Jersey, and Illinois, the shares changed little, but the numbers increased significantly. (Note that the number of unauthorized migrants in each of these six states was larger in 2004 than in 1990, even when the share of the national total decreased.)

This chart shows the high degree of geographic diversification that occurred for the unauthorized population during the 1990s. In 1990, 45% of the unauthorized population, or about 1.6 million persons, lived in California; by 2004, the share had dropped to 24%. Note, however, that because of the sizeable growth in the unauthorized population, California still experienced substantial growth to about 2.4 million or growth of about 45%. Texas’ share increased while New York’s dropped significantly. In Florida, New Jersey, and Illinois, the shares changed little, but the numbers increased significantly. (Note that the number of unauthorized migrants in each of these six states was larger in 2004 than in 1990, even when the share of the national total decreased.)

Outside these six large states, the growth in the unauthorized population was extremely rapid as the share tripled from 12% to 39%. Numerically, the growth was even more striking as the unauthorized population increased almost ten-fold from about 400,000 to 3.9 million. The rapid growth and spreading of the unauthorized population has been the principal driver of growth in the geographic diversification for the total immigrant population into the new settlement states such as Arizona, North Carolina, Georgia, and Tennessee.

Source: Based on Passel 2005 using methods described in Passel et al. 2004.

The geographic diversification of the unauthorized population since 1990 is very evident in this map as many states other than the six major destination states have large unauthorized populations as of 2002–2004. Note that the ranges shown are not contiguous so as to specify more precisely the range of estimates. (See Passel 2005 and next chart for more details.)

The geographic diversification of the unauthorized population since 1990 is very evident in this map as many states other than the six major destination states have large unauthorized populations as of 2002–2004. Note that the ranges shown are not contiguous so as to specify more precisely the range of estimates. (See Passel 2005 and next chart for more details.)

Source: Based on Passel 2005 using methods described in Passel et al. 2004.

States are shown in groupings to emphasize the potential degree of error and variability in the estimates. The ranges are not contiguous so as to specify more precisely the size of the populations. However, the ordering within groups is in approximate order of size of the estimates. For the groups on the right-hand side of the page, the states in smaller type fall near the bottom of the range.

States are shown in groupings to emphasize the potential degree of error and variability in the estimates. The ranges are not contiguous so as to specify more precisely the size of the populations. However, the ordering within groups is in approximate order of size of the estimates. For the groups on the right-hand side of the page, the states in smaller type fall near the bottom of the range.

Source: Based on Passel 2005 using methods described in Passel et al. 2004.

This chart displays the estimated unauthorized population as a percentage of the total foreign-born population in the state.

This chart displays the estimated unauthorized population as a percentage of the total foreign-born population in the state.

In 17 new settlement states* stretching from the northwest through the mountain states to the southeast, the unauthorized make up 40% or more of the total foreign-born population. Of the six traditional settlement states, only Texas has such a large ratio of unauthorized population to the total foreignborn. In the other five traditional unauthorized states, unauthorized migrants make up less than 30% of the foreign-born population and in New York the unauthorized share is less than 20%. (Note that the five highest shares, shown with shaded colors, are part of the top group of 17 states.)

The new growth states with high shares of unauthorized face special challenges because many do not have the social infrastructure needed to deal with newcomer populations to begin with (Passel et al. 2002). In those areas, the challenges of dealing with a newcomer population are simply exacerbated by the clandestine nature of the unauthorized group.

Source: Based on Passel 2005 using methods described in Passel et al. 2004. See also pages 3, 7–9, and 11. See Passel et al. 2002 for definitions of “traditional” and “new settlement” states.

This chart subdivides the entry cohorts of Mexican migrants by legal status (and presents the data in bars that represent the average annual flows).

This chart subdivides the entry cohorts of Mexican migrants by legal status (and presents the data in bars that represent the average annual flows).

The cohorts who have entered from Mexico since 1990 (i.e., in the U.S. for 14 years or less) are principally unauthorized. This trend translates into an average of about 400,000-485,000 annual unauthorized entrants from Mexico. Of those cohorts in the country more than 14 years, most are legal residents. For those entering before 1985, virtually all are legal. (In fact, the unauthorized component shown for the pre-1985 entrants may be largely estimation and sampling error.)

These data should, however, be interpreted cautiously. The data do not necessarily support the idea that the share of Mexican migration that is unauthorized has been increasing in recent years. The earlier cohorts (i.e., pre-1990) had also been largely unauthorized when they had been in the country for shorter durations. That is, the Mexican-born population in the United States for less than 5 years was found to be at least 75% unauthorized in estimates made for 1995, 1990, 1986, and 1980. These earlier entry cohorts are now almost all legal as a result of three processes:

- A “normal” transition from unauthorized to legal through sponsorship and 245(i);

- The legalization programs of the late 1980s; and

- Selective return migration to Mexico by unauthorized migrants.

There is some suspicion that the more-or-less orderly transition process in (1) may have been short-circuited by the legislative changes of the late 1990s, especially affecting 245(i). If true, this change could partially explain the buildup in the unauthorized Mexican population.

Source: Based on Passel 2005 using methods described in Passel et al. 2004.

This next section of this report focuses on a broader range of characteristics of the unauthorized population. Specifically, we first investigate the age, sex, and family structure of the unauthorized population. We introduce here the concept of “mixed families” which in this context has one or two parents who are unauthorized migrants and at least one child who is a U.S. citizen. The unauthorized population contains a significant number of solo males and females, but more of the unauthorized are in couples, either with or without children. Most of the children in unauthorized families are U.S. citizens by birth.

This next section of this report focuses on a broader range of characteristics of the unauthorized population. Specifically, we first investigate the age, sex, and family structure of the unauthorized population. We introduce here the concept of “mixed families” which in this context has one or two parents who are unauthorized migrants and at least one child who is a U.S. citizen. The unauthorized population contains a significant number of solo males and females, but more of the unauthorized are in couples, either with or without children. Most of the children in unauthorized families are U.S. citizens by birth.

We also examine labor force participation of unauthorized migrants, their education, and the occupations and industries in which they work. Labor force participation of unauthorized men is very high while that of women is lower. Finally, we turn to the income of unauthorized workers and how that affects family poverty levels. Not surprisingly, unauthorized workers have relatively low levels of education which translates into low incomes and high poverty levels.

Data, Sources, and Methods: The data presented in this section are drawn principally from the March 2004 CPS, but augmented to include immigration status for migrants included in the CPS. The data and techniques employed were developed initially at the Urban Institute by Passel and Clark. (See Passel and Clark 1998 and Passel, Van Hook, and Bean 2005 for description of the various methods used.) The methods involve estimating the number of unauthorized migrants included in the CPS with the techniques described previously. In this process, the CPS data are first corrected for over-reporting of naturalized citizenship on the part of aliens. Then, persons entering the U.S. as refugees and individuals holding certain kinds of temporary visas (including students, diplomats, and “high-tech guest workers”) are identified in the survey and assigned an immigration status using information on country of birth, date of entry, occupation, education, and various family characteristics. Then, individuals that are definitely legal and those that are potentially unauthorized are identified in the CPS (based on state of residence, age, sex, occupation, country of birth, and date of entry). Finally, using probabilistic methods, enough are selected and assigned to be unauthorized so as to hit the estimated populations. The last step involves a consistency edit to ensure that the family structure of both legal and unauthorized populations “make sense.” The whole process requires several iterations to produce survey-based estimates that agree with the demographically-derived population totals.

This chart shows estimates of family composition for families4 in which the head or spouse is unauthorized based on the March 2004 CPS.

This chart shows estimates of family composition for families4 in which the head or spouse is unauthorized based on the March 2004 CPS.

Unauthorized migrant families contain 13.9 million persons, including the 10.3 million unauthorized migrants. There are 1.6 million children (under 18) in these families, representing about 14% of all unauthorized migrants. In addition, these families include more than 3 million children who are U.S. citizens by birth.

About 56% of the 8.8 million adult unauthorized migrants are men. Additionally, there are about 400,000 other adults in these unauthorized families.

Although the stereotype of unauthorized migrants is that of single adults without families coming to the United States, fewer than half of the adult men (2.3 million or 46%) are single and unattached—the rest are mostly in married couples although some are in other types of families. Among the adult women, about 750,000, or only one in five, is single and unattached.

Source: Based on Urban Institute data from March 2004 CPS with legal status assigned. The CPS does not include direct information on unauthorized status or any legal status, other than naturalization. Status assignments use methods of Passel and Clark 1998 and Passel, Van Hook, and Bean 2004, 2005. See also note on page 17.

Estimates include an allowance for persons not covered by the March 2004 CPS.

This chart examines the structure of families in which either the head or spouse is unauthorized.

This chart examines the structure of families in which either the head or spouse is unauthorized.

There are 6.3 million unauthorized migrant families in 2004 (containing the 13.9 million persons shown in the previous chart). Most of these families—3.7 million or 59%—do not contain children; that is they consist of single adults, couples, or some other combination of relatives. About half of all unauthorized families are solo adults without children (or the “stereotypical” unauthorized migrant) with 2.3 million solo male “families” accounting for just over one-third of the families and 740,000 solo females; these two groups make up 80% of the families without children.

A significant share of unauthorized families can be characterized as “mixed status” in which there is one or more unauthorized parent and one or more children who are U.S. citizens by birth. There are 1.5 million unauthorized families where all of the children are U.S. citizens; these families are about one-quarter of all unauthorized families and 58% of unauthorized families with children. In addition, there are another 460,000 mixed status families in which some children are U.S citizens and some are unauthorized.

About 10% of all unauthorized families have children who are all unauthorized themselves. This group of families is “not mixed status.” However, it represents slightly less than one-quarter of the unauthorized families with children and only 10% of all unauthorized families.

Source: Based on Urban Institute data from March 2004 CPS with legal status assigned. The CPS does not include direct information on unauthorized status or any legal status, other than naturalization. Status assignments use methods of Passel and Clark 1998 and Passel, Van Hook, and Bean 2004, 2005. Estimates include an allowance for persons not covered by the March 2004 CPS.

This chart changes perspective to examine the structure of unauthorized families with children from the point of view of the children.

This chart changes perspective to examine the structure of unauthorized families with children from the point of view of the children.

Overall, there are 4.7 million children of unauthorized migrants, of whom only 1.6 million or 33% are unauthorized themselves according to the chart on page 18. An even smaller share, 20% of unauthorized children, or 920,000, are in families where everyone is unauthorized (or “not mixed” families. Thus, 80% of the children of unauthorized migrants are in mixed status families. Over half of the children of unauthorized migrant—55% or 2.6 million children—are in families where all of the children are U.S. citizens. Another 620,000 U.S. citizen children and 580,000 unauthorized children are in unauthorized families where some of the siblings are unauthorized and some are U.S. citizens. These mixed status families with mixed status children include about 25% of all of the children of unauthorized migrants.

Source: Based on Urban Institute data from March 2004 CPS with legal status assigned. The CPS does not include direct information on unauthorized status or any legal status, other than naturalization. Status assignments use methods of Passel and Clark 1998 and Passel, Van Hook, and Bean 2004, 2005. Estimates include an allowance for persons not covered by the March 2004 CPS.

This chart shows several measures of age composition for families and compares those families headed by unauthorized migrants with those headed by legal immigrants and natives.

This chart shows several measures of age composition for families and compares those families headed by unauthorized migrants with those headed by legal immigrants and natives.

The general conclusion of these comparisons is that, by almost any measure, unauthorized families are much younger, on the whole than either native families or families of legal immigrants. A much higher share of persons in unauthorized families are children (under 18)—35% among unauthorized families versus 29% among legal immigrant families and only 24% among native families. At the other end of the age spectrum, virtually none of the unauthorized population is elderly (65 and over). In contrast, about 1 in 6 native adults and the same share of legal immigrant adults is aged 65 or older.

Among working-age (18-64) adults, the unauthorized population is also substantially younger. Almost all (84%) of unauthorized migrants in this age range are under age 45. In contrast, only about three-fifths of native and legal immigrants of working age are under 45.

Source: Based on Urban Institute data from March 2004 CPS with legal status assigned. The CPS does not include direct information on unauthorized status or any legal status, other than naturalization. Status assignments use methods of Passel and Clark 1998 and Passel, Van Hook, and Bean 2004, 2005.

This chart reports on two aspects of educational progression among post-high school-age youth (i.e., ages 18–24 years):

This chart reports on two aspects of educational progression among post-high school-age youth (i.e., ages 18–24 years):

- Unauthorized youth are much more likely to have dropped out (that is, not completed high school)—50% of unauthorized youth versus 21% of legal immigrants and only 11% of natives. This result needs to be interpreted with caution when considering the implications for the education system, however. Many of the immigrant youth who are classified as “dropouts” never actually attended school in the U.S. Further, many stopped attending school before even entering high school.

- The converse—progressing to attend at least some college after high school—is much more common among natives and legal immigrants than among unauthorized youth. About half of unauthorized high school graduates are not attending or have not attended college. In contrast, almost three-quarters of legal immigrant and native youth have formal education beyond high school.

Source: Based on Urban Institute data from March 2004 CPS with legal status assigned. The CPS does not include direct information on unauthorized status or any legal status, other than naturalization. Status assignments use methods of Passel and Clark 1998 and Passel, Van Hook, and Bean 2004, 2005. See also notes on pages 17, 18, and 21.

This chart addresses the educational attainment of the working-age population that is likely to have completed the major portion of their education—that is, persons ages 25 to 64 years.

This chart addresses the educational attainment of the working-age population that is likely to have completed the major portion of their education—that is, persons ages 25 to 64 years.

Immigrants in general, but especially the unauthorized are considerably more likely than natives to have very low levels of education. For example, less than 2% of natives have less than a 9th grade education, but 15% of legal immigrants and 32% of unauthorized migrants have this little education. (Note that education in Mexico is currently compulsory only through the 8th grade, so finding this many with this little education is not surprising. Further, the level of compulsory school attendance was recently raised from 6th grade.)

At the upper end, legal immigrants are slightly more likely to have a college degree than natives (32% versus 30%). This difference is particularly noteworthy given the high percentage of legal immigrants with very little education. Even the unauthorized population has some at the upper end of the educational spectrum, with 15% having at least a college degree and another 10% having some college. Not all of the unauthorized population fits the stereotype of a poorly educated manual laborer.

Source: Based on Urban Institute data from March 2004 CPS with legal status assigned. The CPS does not include direct information on unauthorized status or any legal status, other than naturalization. Status assignments use methods of Passel and Clark 1998 and Passel, Van Hook, and Bean 2004, 2005.

This chart offers a bit more detail on legal status and duration of residence than the previous chart while depicting the low end of the educational spectrum (i.e. less than a high school education) and the high end (B.A. or greater) for all immigrants by legal status.

This chart offers a bit more detail on legal status and duration of residence than the previous chart while depicting the low end of the educational spectrum (i.e. less than a high school education) and the high end (B.A. or greater) for all immigrants by legal status.

Some have characterized the educational distribution of immigrants as an “hourglass” because immigrants tend to be over-represented at both extremes relative to natives; with natives, the concentration is in the middle, hence the characterization of native education distribution as a “diamond.” However, as this chart highlights, the high proportion with low levels of education found among immigrants is due principally to unauthorized migrants and older cohorts of legal immigrants. The larger proportion with college degrees can be traced to naturalized citizens and recent legal immigrants. In fact, by 2004, all groups of legal immigrants in the country for less than 10 years are more likely to have a college degree than natives, notwithstanding the continued over-representation of legal immigrants at low levels of education.

This chart illustrates, too, the upgrading of education among recent legal immigrants in contrast to longer-term residents. It also illustrates some of the selectivity in the naturalization process. Among legal immigrants in the country 10 years or more, a much higher proportion of those who have naturalized have college degrees than among those who have not.

Source: Based on Urban Institute data from March 2004 CPS with legal status assigned. The CPS does not include direct information on unauthorized status or any legal status, other than naturalization. Status assignments use methods of Passel and Clark 1998 and Passel, Van Hook, and Bean 2004, 2005.

This chart displays labor force participation rates for the working-age population by sex and legal status.

This chart displays labor force participation rates for the working-age population by sex and legal status.

Labor force participation differs substantially by sex and across the groups defined by immigration status. Among men ages 18–64, natives are the least likely to be in the civilian non-institutional labor force (83%) followed by legal immigrants (86%) and then by the group most likely to be working—the unauthorized (92%). There appear to be a number of factors associated with these differences. One of the simplest is age. Within this age range for workers, those who are older (e.g., 45–64) are more likely to be retired or disabled and so, not in the labor force. Very few unauthorized fall in this age range, so overall, they are simply more likely to be working.

In addition to disability and retirement, the other principal reason for men not being in the labor force is that they are attending college. Again, very few unauthorized attend college so their labor force participation is higher. Finally, if unauthorized persons do become disabled or retire, they are much more likely than others to leave the country and, thus, not appear in the U.S. labor force.

Participation patterns among women are just the opposite—with unauthorized being the lowest and natives being the highest. The principal reason women do not participate in the labor force is the presence of young children in their family. Secondarily, unmarried women are more likely than married women to participate in the workforce. Immigrant women are more likely to be married than native women; they are also considerably more likely than natives to have children. Among unauthorized migrant women, this pattern is even stronger because more of them are from high fertility areas.

Source: Based on Urban Institute data from March 2004 CPS with legal status assigned. The CPS does not include direct information on unauthorized status or any legal status, other than naturalization. Status assignments use methods of Passel and Clark 1998 and Passel, Van Hook, and Bean 2004, 2005.

This chart shows the distribution of unauthorized migrants across occupations by combinations of the CPS’ 10 “major occupation groups” for those migrants who are in the labor force. (The distribution of native workers is shown in parentheses.)

This chart shows the distribution of unauthorized migrants across occupations by combinations of the CPS’ 10 “major occupation groups” for those migrants who are in the labor force. (The distribution of native workers is shown in parentheses.)

Unauthorized migrants account for about 4.3% of the civilian labor force or about 6.3 million workers out of a labor force of 146 million. ([Note that these data are not adjusted for persons omitted from the CPS. Were they corrected for omissions,the number of unauthorized migrants in the labor force would probably be about 675,000–700,000.) Although the unauthorized workers can be found throughout the workforce, they tend to be over-represented in certain occupations and industries. The next several charts attempt to identify some of these concentrations.

Unauthorized workers are conspicuously sparse in white collar occupations compared with native. “Management, business, and professional occupations” and “Sales and administrative support occupations” account for over half of native workers (52%) but less than one-quarter of unauthorized workers (23%). On the other hand, unauthorized migrants are much more likely to be in broad occupation groups that require little education or do not have licensing requirements. The share of unauthorized who work in agricultural occupations and construction and extractive occupations is about three times the share of native workers in these types of jobs.

Source: Based on Urban Institute data from March 2004 CPS with legal status assigned. The CPS does not include direct information on unauthorized status or any legal status, other than naturalization. Status assignments use methods of Passel and Clark 1998 and Passel, Van Hook, and Bean 2004, 2005.

This chart shows the proportion of workers who are unauthorized migrants in a selection among the CPS’ 27 “detailed occupation groups”. The major occupations shown are those where the proportion of unauthorized migrants exceeds the proportion in the workforce (4.3%).

This chart shows the proportion of workers who are unauthorized migrants in a selection among the CPS’ 27 “detailed occupation groups”. The major occupations shown are those where the proportion of unauthorized migrants exceeds the proportion in the workforce (4.3%).

Within the broad occupation groupings shown in this chart and the previous ones, there are selected occupations with very high concentrations of unauthorized migrants. The following specific occupation groups have both significant numbers and high concentrations of unauthorized migrants. For example more than 1 out of every 4 (or 27% of) drywall/ceiling tile installers in the U.S. is an unauthorized migrant. These occupations are grouped roughly by broad categories and generally share the characteristics noted earlier—no governmental licensing or education credentials are required.

- Drywall/ceiling tile installers… 27%

- Cement masons & finishers 22%

- Roofers 21%

- Construction laborers 20%

- Painters, construction etc. 20%

- Brick/block/stone masons 19%

- Carpenters 12%

- Grounds maint. workers 26%

- Misc. agricultural workers 23%

- Hand packers & packagers 22%

- Graders & sorters, ag. prod. 22%

- Butchers/ meat, poultry wrkrs 25%

- Dishwashers 24%

- Cooks 18%

- Dining & cafeteria attendants 14%

- Food prep. workers 13%

- Janitors & bldg cleaners 12%

- Maids & housekeepers 22%

- Sewing machine operators 18%

- Cleaning/washing equip. oper 20%

- Packaging/filling mach. oper. 17%

- Metal/plastic workers, other 13%

This chart shows the distribution of unauthorized migrants across industries by combinations of the CPS’ 14 “major industry groups” for those migrants who are in the labor force. The specific groups shown are those where the distribution of unauthorized workers approximates or exceeds the distribution of natives.

This chart shows the distribution of unauthorized migrants across industries by combinations of the CPS’ 14 “major industry groups” for those migrants who are in the labor force. The specific groups shown are those where the distribution of unauthorized workers approximates or exceeds the distribution of natives.

The concentration of unauthorized workers in broad industries is not as marked as the concentration in broad occupation groups. Only in “leisure & hospitality” and in “construction” does the share of unauthorized workers greatly exceed the share of natives. Somewhat greater than 1 in 6 unauthorized workers is in the the leisure & hospitality industry (18%) or the construction industry (17%). Only about 7%–8% of native workers is in each of these industries. Neither of these industries tends to require credentials from prospective workers. Further, there are many occupations in these industries that do not require much in the way of education.

The remaining broad industries where roughly the same shares of natives and are in services, retail trade, and manufacturing.

Source: Based on Urban Institute data from March 2004 CPS with legal status assigned. The CPS does not include direct information on unauthorized status or any legal status, other than naturalization. Status assignments use methods of Passel and Clark 1998 and Passel, Van Hook, and Bean 2004, 2005.

This chart shows the proportion of workers who are unauthorized migrants in a selection among the CPS’ 52 “detailed industry groups” . The major industries shown are those where the proportion of unauthorized migrants exceeds the proportion in the workforce (4.3%).

This chart shows the proportion of workers who are unauthorized migrants in a selection among the CPS’ 52 “detailed industry groups” . The major industries shown are those where the proportion of unauthorized migrants exceeds the proportion in the workforce (4.3%).

There are fewer detailed industries with high concentrations and significant numbers of unauthorized workers than detailed occupations. The range of credential and educational requirements is generally broader for industries than for occupations. Nonetheless, there are some industries with very high concentration of unauthorized workers. For example, 26% of workers in the landscaping services industry are unauthorized; similarly, about 1 in 5 workers in meat/poultry packing is unauthorized. The following industries have more than twice the representation of unauthorized workers than the whole labor force.

- Landscaping services 26%

- Private households 14%

- Animal slaughter & process. 20%

- Traveler accommodation 14%

- Services to bldgs & homes 19%

- Restaurants & food services 11%

- Dry cleaning & laundry 17%

- Construction 10%

- Cut & sew apparel mfg 16%

- Groceries & related prod 8%

- Crop production 16%

Source: Based on Urban institute data from March 2004 CPS with legal status assigned. The CPS does not include direct information on unauthorized status or any legal status, other than naturalization. Status assignments use methods of Passel and Clark 1998 and Passel, Van Hook, and Bean 2004, 2005.

This chart shows average family income, average family size, and average income per person for natives, legal immigrants, and unauthorized migrants based on the March 2004 CPS.

This chart shows average family income, average family size, and average income per person for natives, legal immigrants, and unauthorized migrants based on the March 2004 CPS.

The incomes of unauthorized migrants and their families shown here reflect the comparative levels of education shown earlier and the occupations/industries where they work. Specifically, average family income of unauthorized migrant families is more than 40% below the average income of either legal immigrant or native families. In addition to education and occupation differences, another factor contributing to this difference is the lower labor force participation of unauthorized females that results in fewer workers per family than in the other groups.

Immigrants tend to have somewhat larger families on average than natives, with little difference in family size between unauthorized and legal immigrants.

A key element of income is the amount available per person in the family. Because unauthorized families tend to be larger with lower incomes than natives, the difference in average income per person5 is even larger than the difference in income. Thus, the average income per person in unauthorized families ($12,000) is about 40% less than legal immigrant families and more than 50% below the per capita income in native families.

Source: Based on Urban Institute data from March 2004 CPS with legal status assigned. The CPS does not include direct information on unauthorized status or any legal status, other than naturalization. Status assignments use methods of Passel and Clark 1998 and Passel, Van Hook, and Bean 2004, 2005.

This chart shows more detail on average family income than the previous chart using data from the March 2004 CPS by incorporating specific legal statuses and duration of residence.

This chart shows more detail on average family income than the previous chart using data from the March 2004 CPS by incorporating specific legal statuses and duration of residence.

The data clearly show that incomes are higher for immigrants who have been in the U.S. for more than 10 years, compared with more recently arrived immigrants. Average family income for both legal immigrants and refugees in the U.S. for more than 10 years is only 2–3% below that of natives. For longer-term naturalized citizen families, average family income is 23% higher than native income.

The incomes of unauthorized migrants do not show the same pattern of increase with longer durations of residence. For those in the U.S. more than 10 years, family incomes are only about one-sixth higher than the shorter-term unauthorized ($29,900 versus $25,700) and remain 35% below the incomes of native families. The relatively low incomes of unauthorized migrants in the country for more than 10 years most likely reflects a lack of opportunities for economic mobility among those who remain in an unauthorized status. Many unauthorized migrants are able to become legal immigrants after 10 or more years in the U.S. Those who are left as unauthorized may not be able to take advantage of a range of jobs available; that is, they may be “stuck” in lower-paying jobs.

Source: Based on Urban Institute data from March 2004 CPS with legal status assigned. The CPS does not include direct information on unauthorized status or any legal status, other than naturalization. Status assignments use methods of Passel and Clark 1998 and Passel, Van Hook, and Bean 2004, 2005.

This chart also shows more detail on average family size than the previous chart using data from the March 2004 CPS by incorporating specific legal statuses and duration of residence.

This chart also shows more detail on average family size than the previous chart using data from the March 2004 CPS by incorporating specific legal statuses and duration of residence.

Immigrants, regardless of status and duration of residence, have larger families than natives, on average. In addition, those immigrants in the U.S. for more than 10 years have larger families than the shorter duration immigrants. Also, the families of noncitizens tend to be larger than those of naturalized citizens. The recently-arrived immigrants are, on average, younger than the other immigrants and so are less likely to be married and tend to have fewer children. Over time, as the short-term immigrants remain in the U.S., they can be expected to have family sizes approaching those of the longer-term immigrants.

Source: Based on Urban Institute data from March 2004 CPS with legal status assigned. The CPS does not include direct information on unauthorized status or any legal status, other than naturalization. Status assignments use methods of Passel and Clark 1998 and Passel, Van Hook, and Bean 2004, 2005.

This chart follows the previous two by showing more detail on average family income per person than the previous chart with data from the March 2004 CPS on specific legal statuses and duration of residence. Average income per person is defined as average family income divided by average family size.

This chart follows the previous two by showing more detail on average family income per person than the previous chart with data from the March 2004 CPS on specific legal statuses and duration of residence. Average income per person is defined as average family income divided by average family size.

When family size is taken into account and incomes are converted to a per capita basis, even the somewhat higher-income immigrant groups tend to suffer in comparison with native families. Only among naturalized citizens in the U.S. more than 10 years do per capita family incomes exceed those of natives. Per capita incomes for unauthorized families are less than half of natives’ per capita incomes. For LPR aliens and refugees, per capita family incomes are 30-40% below those of U.S. natives. Note that these differences exceed those expected purely on the basis of average levels of education.

For unauthorized migrant families, per capita incomes of the longer-term residents are less than half those of natives’ and an even smaller fraction than those of more recent unauthorized migrants. This pattern reinforces the lack of opportunities available to the longer-term unauthorized as those who manage to acquire legal status probably do better than those who do not. The nature of jobs available to the unauthorized, the role of employers, and the potential lack of opportunities for changing jobs may all play a role in the continued low incomes of unauthorized migrants even as they accumulate experience in the U.S.

Source: Based on Urban Institute data from March 2004 CPS with legal status assigned. The CPS does not include direct information on unauthorized status or any legal status, other than naturalization. Status assignments use methods of Passel and Clark 1998 and Passel, Van Hook, and Bean 2004, 2005.

This chart shows the proportion of adults and children in families with incomes below the federal poverty level on the basis of the March 2004 CPS. Children are identified by their own nativity and by the status of their parents; adults, by their own status.

This chart shows the proportion of adults and children in families with incomes below the federal poverty level on the basis of the March 2004 CPS. Children are identified by their own nativity and by the status of their parents; adults, by their own status.

Poverty levels naturally reflect the income patterns just shown in the previous charts. Immigrant adults are more likely than natives to live in families with incomes below poverty level. Unauthorized migrants are more than twice as likely to be living in poverty than native adults.

Children have higher levels of poverty than adults across all groups. However, children of immigrants have much higher levels of poverty than children of natives. The status of the child has a separate effect on poverty as U.S.-born children of immigrants have somewhat lower levels living below the poverty level than immigrant children of immigrants. This pattern reflects the status of the children’s families, but a principal determinant of the difference is probably duration of residence in the U.S. Immigrant families with U.S.-born children tend to have been in the U.S. longer on average than immigration families with only immigrant children.

Source: Based on Urban Institute data from March 2004 CPS with legal status assigned. The CPS does not include direct information on unauthorized status or any legal status, other than naturalization. Status assignments use methods of Passel and Clark 1998 and Passel, Van Hook, and Bean 2004, 2005.

This chart shows the proportion of adults and children in families without health insurance at any point in 2003 on the basis of the March 2004 CPS. Children are identified by their own nativity and by the status of their parents; adults, by their own status.

This chart shows the proportion of adults and children in families without health insurance at any point in 2003 on the basis of the March 2004 CPS. Children are identified by their own nativity and by the status of their parents; adults, by their own status.

Immigrant adults are much more likely than natives to lack health insurance. More than half of unauthorized adults do not have insurance. A principal factor affecting this pattern is that the occupations and industries in which the unauthorized work tend to be those where employers do not provide insurance.

Although poverty levels for children are higher than those of adults, children are more likely to have health insurance than adults. This pattern undoubtedly reflects the availability of coverage through the State Children’s Health Insurance Program (SCHIP) in recent years. Children of immigrants are less likely to be covered by health insurance than children of natives, reflecting their higher levels of poverty and the lack of insurance on the part of their parents. Here again, the status of the child has a separate effect on coverage as U.S.-born children of immigrants are more likely to have insurance than children who are immigrants themselves. Legal immigrant children, while having high levels without insurance (25%), are much more likely to be covered than unauthorized children (59%). Here, the children are not eligible for SCHIP because of their status and their parents generally do not have coverage for themselves or their families.

Source: Based on Urban Institute data from March 2004 CPS with legal status assigned. The CPS does not include direct information on unauthorized status or any legal status, other than naturalization. Status assignments use methods of Passel and Clark 1998 and Passel, Van Hook, and Bean 2004, 2005.

The final section of this background report covers the magnitude of Mexican migration to the U.S. in the context of Mexican population growth and presents the implications for future growth of this population in the U.S. of projected population growth in Mexico.

The final section of this background report covers the magnitude of Mexican migration to the U.S. in the context of Mexican population growth and presents the implications for future growth of this population in the U.S. of projected population growth in Mexico.

The major highlights of the demography of Mexico and Mexican migration to the U.S. are:

Very large flows to the U.S. have resulted in a significant share—about 9%—of the Mexican-born population residing in the U.S.

The major highlights of the demography of Mexico and Mexican migration to the U.S. are:

- Very large flows to the U.S. have resulted in a significant share—about 9%—of the Mexican-born population residing in the U.S.

- Large-scale migration with settlement in the U.S. began in the mid-1970s and has grown steadily over the last several decades. Flows increased dramatically beginning about 1997–98. Current data do not show a dramatic response to either 9/11 or the post-2001 recession. Large flows are continuing but there is some suggestion of a very slight decrease with levels falling to those of the mid-1990s.

- A very high percentage (80–85%) of new migrants are unauthorized. Overall, about half of Mexicans in the U.S. are unauthorized.

- The flows respond to economic conditions in Mexico more than to conditions in the U.S. with worsening conditions in Mexico leading to increased migration to the United States. Settlement patterns in the U.S. respond increasingly to the availability of jobs.

- New destinations emerged in the late 1990s. Traditional settlement areas (e.g., CA, TX, IL, AZ) continued to attract migrants but a much larger share went to new destinations.

- Mexico’s population is continuing to grow, but the rate of growth has decreased as fertility has fallen. Labor force entry cohorts will begin to decrease in size shortly after 2010.

This chart shows the Mexican-born population of the United States as measured by decennial censuses and the CPS for 1850–2004 and what proportion this group is of the U.S. foreign-born population.

This chart shows the Mexican-born population of the United States as measured by decennial censuses and the CPS for 1850–2004 and what proportion this group is of the U.S. foreign-born population.

While the U.S. and Mexico have always had interrelated populations and Mexicans have been coming to work in the United States since the 19th century, large-scale settlement in the U.S. is a relatively recent phenomenon—something that is often overlooked. As recently as 1970, Mexico had only the 4th largest foreign-born population—behind Italy, Germany, and Canada. (In 1960, there were more Britons, Poles, and Russians, too.)

The large increases in numbers of Mexicans actually moving to the U.S. that began in the 1960s, accelerated in the 1970s as the number of Mexicans in the U.S. tripled between 1970 and 1980. The number doubled again by 1990 and again by 2000. In 2004, the March CPS shows 10.6 million people born in Mexico. This figure represents more than a 13-fold increase over the 1970 census.

Mexicans account for about 31–32% of all immigrants, by far the largest country of origin and more than five times the next largest population. (Note that this degree of concentration from one country is not unprecedented. In the late 19th century, Germany and Ireland each accounted for more than 30% of the immigrant population at various times—in some years at the same time.)

Another phenomenon has changed in the past several decades, too. The percentage of the the Mexican population (defined as the population of Mexico plus the Mexican-born population living in the U.S.) that is living in the United States has grown dramatically in recent years. For the period 1950–1970, only about 1.5% of the Mexican population was in the United States (not shown). This share doubled by 1970 and more than doubled again by 1995 (to 6.7%). The rapid growth in Mexicans in the U.S. since the mid-1990s has pushed this share to about 9% by 2004.

Sources: Decennial censuses through 2000 (Campbell and Lennon 1999), Urban Institute and Pew Hispanic Center tabulations of March CPS for 1995–2004.

This chart shows the measured total fertility rate (TFR) for Mexico for 1960–2000 and projected values through 2050 according to the three different projection sources. (Total fertility rates represent the average lifetime fertility of a woman as measured in a given year; replacement level TFR is about 2.05- 2.1.)

This chart shows the measured total fertility rate (TFR) for Mexico for 1960–2000 and projected values through 2050 according to the three different projection sources. (Total fertility rates represent the average lifetime fertility of a woman as measured in a given year; replacement level TFR is about 2.05- 2.1.)

The TFR in Mexico, according to CONAPO (National Population Council of Mexico) surveys, is less than one-third of what it was in 1960 as fertility has dropped from over 7 children per woman to about 2.4 in 2000, or just over replacement level.

Most population projections assume that fertility will continue to fall from 2000 levels. Both the United Nations and CONAPO assume that the Mexican TFR will ultimately reach 1.85, but the CONAPO projections assume a steeper drop. U.S. Census Bureau projections for Mexico assume the TFR will fall to 2.0.

Mexican immigrants in the U.S. actually have higher fertility than all Mexican women by almost one child per woman (3.3 versus 2.4). This surprising difference is the result, in large part, of selective migration from Mexico. In particular, the Mexicans in the U.S. tend to originate from regions experiencing higher fertility rates within Mexico and from groups prone to higher fertility.

Mexican origin women born in the United States have fertility that is only very slightly lower than women in Mexico.

Source: CONAPO (National Population Council of Mexico) website, www.conapo.gob.mx 2003 and author’s computation from US Current Population Survey data for June 1999, 2000, and 2001.

This chart shows historical estimates of net migration from Mexico based on the author’s estimates and projected future levels according to the 3 different projection sources.

This chart shows historical estimates of net migration from Mexico based on the author’s estimates and projected future levels according to the 3 different projection sources.

CONAPO has significantly higher migration than the UN, but does not show much of a decline from the initial values. CONAPO’s assumptions rely on a set of emigration rates but do not fully reflect the new information available from the U.S. Census 2000 on higher levels of migration to the United States during the late 1990s; if they did, the CONAPO projections might have higher current levels of migration to the U.S. as well as higher projected values.

The Census Bureau projections are the only ones that take into account the information on higher levels of migration. The assumptions for the first decade of the projection reflect this new information and show much higher levels of emigration from Mexico than either of the other two projections. However, by 2010, the Census Bureau assumptions are lower than CONAPO’s but higher than the U.N.’s. By 2025, the Census Bureau assumptions differ little from the U.N. assumptions and reflect much lower levels of migration than the CONAPO projections.

The very different assumptions about fertility and migration result in a reasonably large range in population figures for Mexico in 2050 according to the various projections:

- CONAPO 129.6 million

- U.N. (Med.) 140.2 million

- Census 147.9 million

This chart displays the historical information on Mexicans in the United States, as previously displayed, together with projections of Mexicans in the United States based on the CONAPO assumptions about Mexico-U.S. migration.

This chart displays the historical information on Mexicans in the United States, as previously displayed, together with projections of Mexicans in the United States based on the CONAPO assumptions about Mexico-U.S. migration.

The number of Mexicans in the United States is projected to increase steadily from 10.6 million in 2004 to more than 22 million in 2050. At this time, more than 1-in-7 (or 15%) of persons born in Mexico are projected to be living in the United States.

In addition to the migrants in the United States, the Mexicans in the U.S. have children who, were the migrants still living in Mexico, would be Mexican-born. These post-2000 births also represent a sizeable group. By 2050, these post-2000 births to Mexican immigrants living in the U.S. and their descendants amount to another almost 17 million persons in addition to the 22.2 million shown in the chart. Thus, the 39 million Mexican immigrants and their post-2000 U.S.-born descendants would be equal to about 30% of the 130 million Mexicans projected to be living in Mexico.

Note that this scenario should not be treated as a prediction, but rather as the consequences of the assumptions built into the CONAPO projection. This scenario takes into account only the demographic assumptions, not any assumptions about migration policy or enforcement. Under the current immigration policies of the United States, the projected level of Mexico-U.S. migration built into this scenario would imply that at least half of the migration and possibly as much as two-thirds would have to be outside of legal channels. Demographically, these assumptions would imply more than half of the 2050 population of Mexicans in the United States would have to be unauthorized. Whether such a scenario is politically viable is outside the scope of these projections.

Sources: Decennial censuses through 2000 (Campbell and Lennon 1999), Urban Institute and Pew Hispanic Center tabulations of March CPS for 1995-2004, U.S. Census Bureau estimates of the Mexican population, and CONAPO estimates and projections. Projections beyond 2000 by author combining U.S. decennial census and CPS estimates with CONAPO projections of future migration levels.

Some of the major highlights from the analysis of migration flows to the U.S. and the demography of unauthorized migration are:

Some of the major highlights from the analysis of migration flows to the U.S. and the demography of unauthorized migration are:

- Very large flows to the U.S. Immigration flows have increased overall since the 1980s. Much of the increase is due to unauthorized migration.

- A very high percentage of new migrants are unauthorized. Much of the increase in annual immigration to the U.S. is due to increases in unauthorized migration. Since the mid-1990s, the number of new unauthorized migrants has equaled or exceeded the number of new legal immigrants. For Mexico, 80–85% of new settlers in the U.S. are unauthorized.

- The flows respond to economic conditions in the U.S. and abroad. For Mexico and many other countries, conditions in the U.S. are almost always better than abroad so that worsening conditions in Mexico and elsewhere lead to increased migration to the United States.

- New destinations for immigrants (especially Mexicans) emerged in the late 1990s. Settlement patterns in the U.S. respond increasingly to the availability of jobs. Traditional settlement areas (e.g., CA, TX, IL, AZ) continued to attract migrants but a much larger share went to new destinations.

- Current data do not show a dramatic response in the form of a large drop due to either 9/11 or the post-2001 recession. Large flows are continuing but there is some suggestion of a very slight decrease in 2003 and 2004, but immigration is still above levels of the mid-1990s.

This chart focuses on some of the implications of the information presented to be considered in designing policies and programs to deal with unauthorized migration.

This chart focuses on some of the implications of the information presented to be considered in designing policies and programs to deal with unauthorized migration.

- The numbers involved are very large—more than 10 million unauthorized migrants.

- The migrants are scattered around the country with many now living in areas with little institutional structure for dealing with newcomers.

- Most of the unauthorized population is relatively young; many live in families; most of the children of unauthorized migrants are U.S. citizens.

- Almost all unauthorized families have one or more workers, many with 5 or more years in the U.S. Their experience in the U.S. and the presence of wives and U.S.-born children suggests that they may be reluctant to leave the country.

- The data on family incomes suggest that there has been little upward mobility among unauthorized migrants. Yet, after the IRCA legalizations, wages increased for formerly unauthorized migrants, suggesting the potential for mobility among the current group.

- Unauthorized migrants are attracted by economic opportunity (relative to their home countries). Whether the current and previous levels of demand will continue is uncertain. However, even in the post-2000 period, unauthorized migrants have continued to come to the U.S.

- Migratory flows from Mexico are well-established. However, relatively small shares of the unauthorized population hail from Africa and Asia, in part because getting to the U.S. from these parts of the world is difficult.