Many people generally believe that policies in their country would improve if the types of people in politics changed. Having more women, young adults or people from poor backgrounds in office are seen as beneficial, especially by people on the political left.

Fewer expect positive change to come from having more businesspeople, labor union members or religious people hold elected office.

What if more elected officials were women?

Although they make up just under half of the global population, women make up only 26.7% of national legislative bodies around the world, according to the Inter-Parliamentary Union.

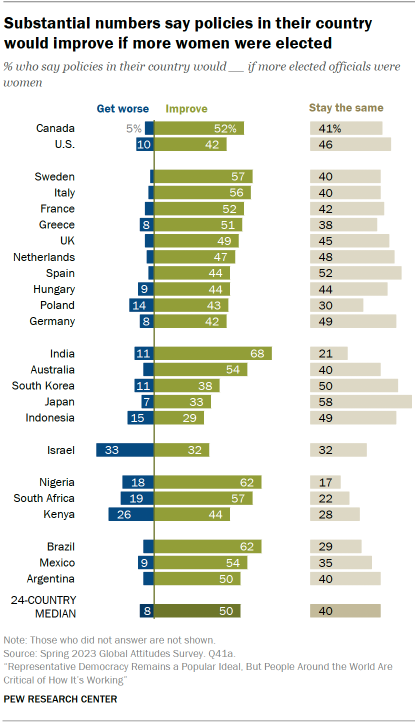

Across the 24 nations surveyed, a median of 50% say policies in their country would improve if more elected officials were women, while a median of only 8% think they would get worse.

A median of 40% say policies would stay the same.

People from India are the most likely to believe policies will improve, with nearly seven-in-ten holding this view. Earlier this year, India adopted a gender quota law that reserves one-third of its parliamentary seats for women.

Meanwhile, Indonesians are the least likely to hold this view: Fewer than one-in-three say policies would improve. A similarly low share holds this view in Japan.

Israel stands out as the only country where views are split. Israelis are just as likely to believe policies would get worse (33%) as they are to say they would improve (32%) or stay the same (32%).

Factors related to views on electing more women

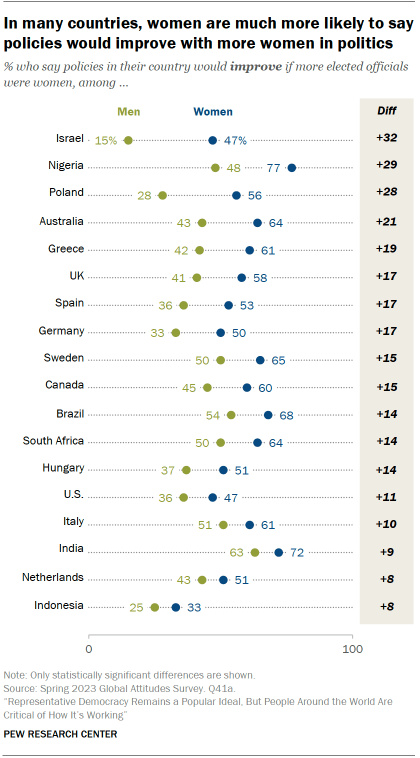

Gender: In 18 countries surveyed, women are more likely than men to say policies would improve if more women were elected to office. This difference is greatest in Israel, where 47% of women hold this view compared with 15% of men.

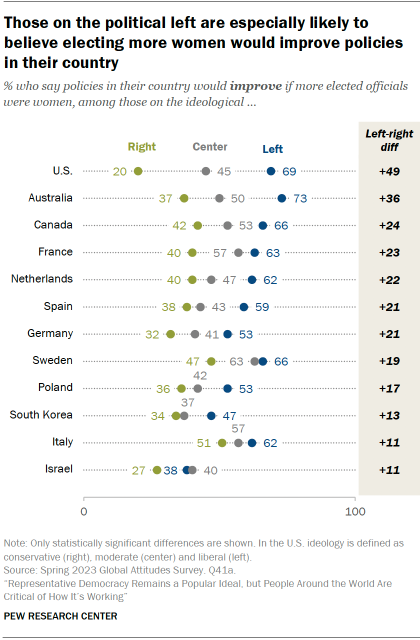

Ideology: In 12 out of the 18 countries where ideology is measured, those on the left are much more likely than those on the right to say policies would improve. For example, large differences exist in the U.S., where nearly seven-in-ten liberals say policies would improve, but only two-in-ten conservatives agree.

Related: Women and Political Leadership Ahead of the 2024 U.S. Election

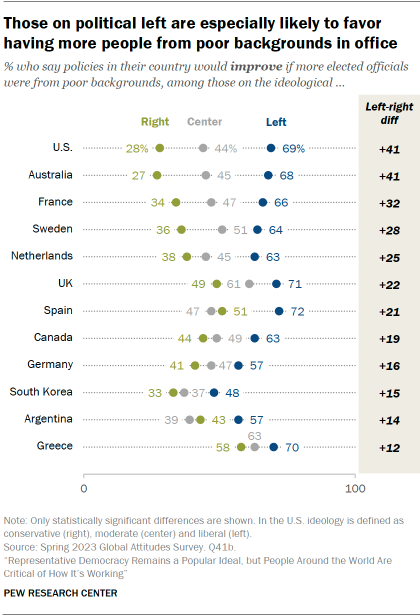

What if more elected officials were from poor backgrounds?

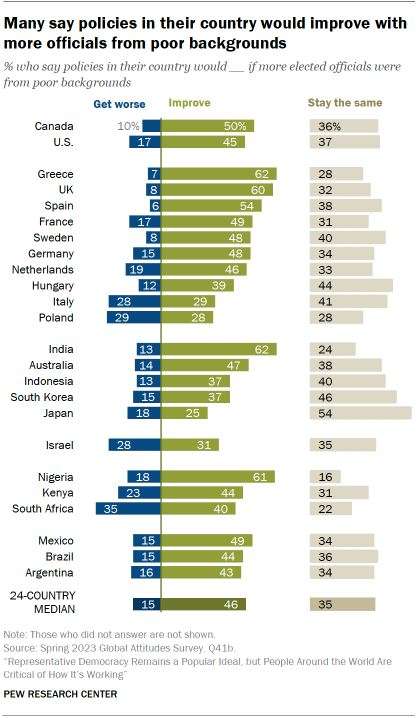

Across the 24 countries surveyed, a median of 46% say that policies would improve if more elected officials were from poor backgrounds. In contrast, a median of 15% say policies would get worse, and about a third say policies would stay the same.

Publics in Greece, India, Nigeria and the UK are the most likely to believe policies would improve, with six-in-ten or more respondents holding this view in each country. And South Africans are the most likely to say policies would get worse.

Factors related to views on electing more people from poor backgrounds

Ideology: In 12 countries, people on the left are somewhat more likely than those on the right to say having more elected officials from poor backgrounds would improve policies.

Ideological differences are largest in Australia and the U.S. In Australia, 68% of those on the left think having people from poor backgrounds in politics would improve policies, compared with just 27% on the right. In the U.S., 69% of liberals hold this view but only 28% of conservatives.

Income: Overall, views do not vary greatly based on income. However, in France, Germany, Israel, Japan and the Netherlands, people with lower incomes are more likely than those with higher incomes to say policies would improve if more people in elected leadership were from poor backgrounds.

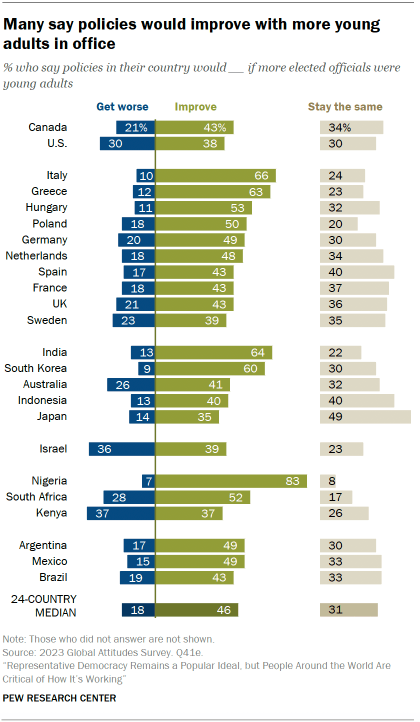

What if more elected officials were young adults?

A median of 46% across 24 countries believe policies would improve if more elected officials were young adults. A median of 18% believe policies would get worse, while 31% believe they would stay the same.

In Nigeria, which held elections just before the survey was conducted, respondents are especially likely to say policies would improve, with more than eight-in-ten holding this view.

Half or more in Greece, Hungary, India, Italy, Poland, South Africa and South Korea share this sentiment.

Conversely, people in Japan are the least likely to think policies would be positively impacted: Just over one-third say policies would be better if more young adults were in office.

Negative views about electing more young people are particularly common in Kenya, Israel and the U.S. In each of these nations, at least three-in-ten believe policies would get worse if more elected officials were young adults.

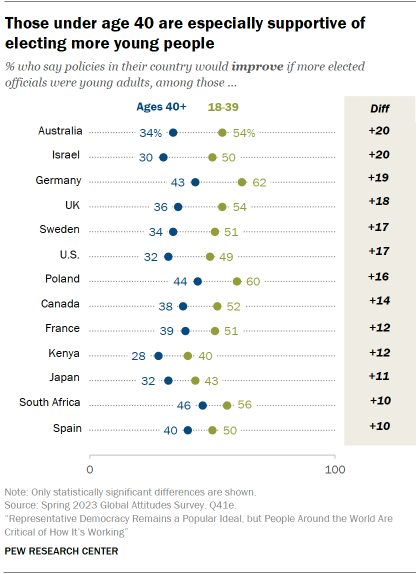

Factors related to views on electing more young adults

Age: In 13 countries, adults under 40 are significantly more likely than those 40 and older to say young politicians would positively impact policy. For example, in Australia and Israel, half of younger adults hold this view, compared with about three-in-ten older adults.

However, there are two notable exceptions: In Argentina and South Korea, adults 40 and older are more likely to say policies would improve if more younger officials were elected.

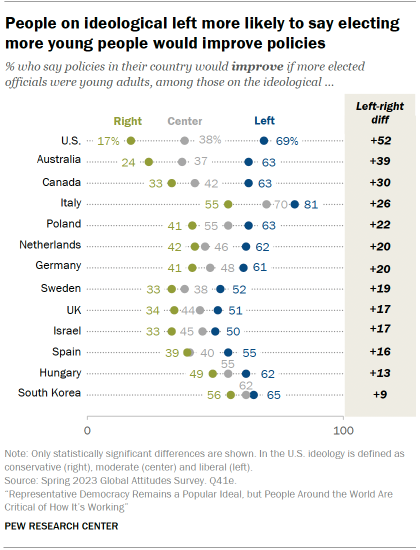

Ideology: Differences appear along ideological lines in 13 countries. In all cases, those on the left are more likely than those on the right to say more young people in office would improve policies.

Several countries stand out with particularly wide ideological divides on this issue.

In Canada, there is a 30 percentage point difference between the left and the right. In Australia, the difference is even more pronounced: 63% of those on the left think policies would improve, compared with 24% on the right.

The gap is the widest in the U.S., where nearly seven-in-ten liberals say electing more young adults would improve policies but fewer than two-in-ten conservatives share this view.

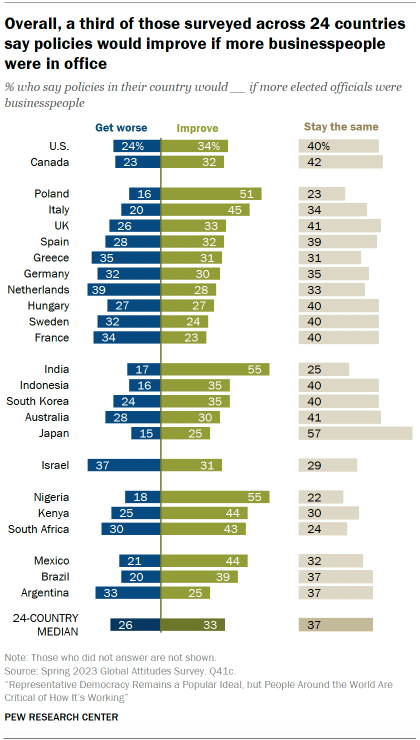

What if more elected officials were businesspeople?

A median of one-third say policies would improve if more elected officials were businesspeople. About a quarter say policies would get worse, and a median of 37% say things would stay the same.

About half or more of Indians, Nigerians and Poles say that more businesspeople in elected office would improve policies.

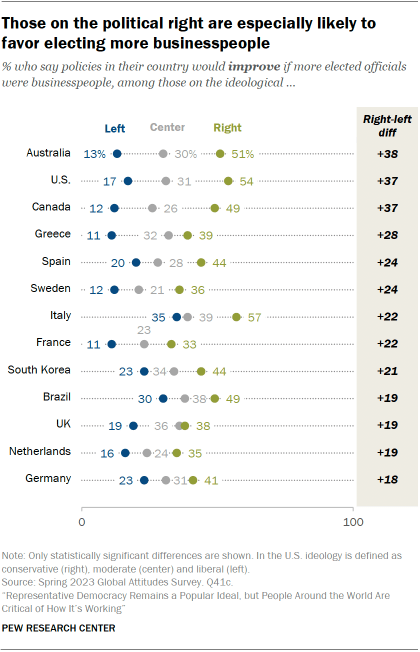

How ideology is connected to views of electing more businesspeople

In 13 of the 18 countries where we ask about people’s political ideologies, those on the right are more likely than those on the left to say more businesspeople in office would improve policies. Differences are largest in Australia, Canada and the U.S. A large difference exists in Greece as well.

We see the opposite relationship in Poland: 65% of Poles on the ideological left say that more businesspeople in elected office would improve policies, compared with 42% who hold this view on the right – a 23 percentage point difference.

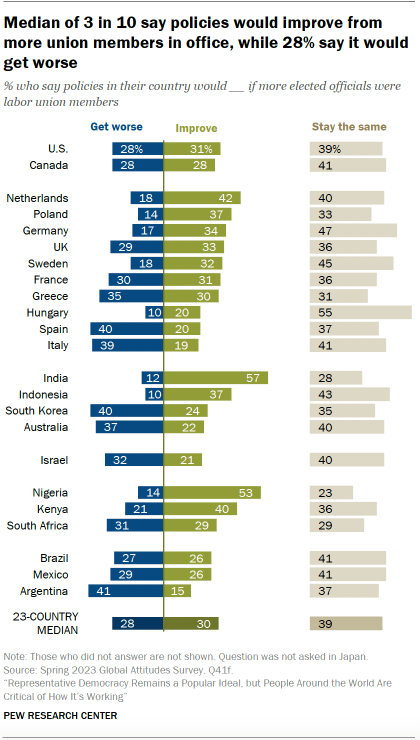

What if more elected officials were labor union members?

A median of 30% say policies would improve if more elected officials were labor union members. About the same share say policies would get worse. However, roughly four-in-ten say policies would neither improve nor get worse.

About six-in-ten Indians and half of Nigerians say more labor union members as elected officials would improve policies. Argentines are the least convinced, with just 15% saying this.

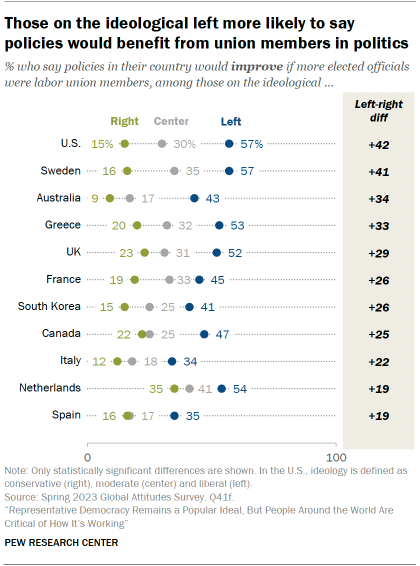

How ideology impacts views of electing more union members

In several countries, people on the ideological left are more likely to say that union members would improve policies. This gap is largest in the U.S., where 57% of liberals hold this view compared with 15% of conservatives, and in Sweden, where 57% on the left hold this view but just 16% on the right.

In the U.S. – the only country where we have a measure of union membership in the survey – 48% of union members think policies would improve, compared with just 29% of respondents who do not belong to a union.

What if more elected officials were religious?

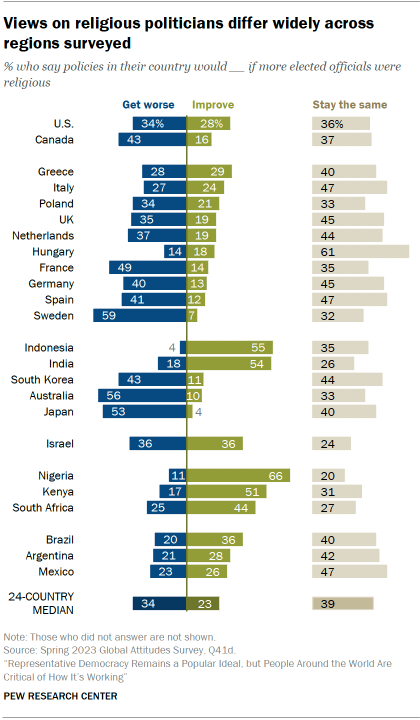

Across the 24 nations polled, a median of 23% say policies would improve if more elected officials were religious, while 34% say policies would get worse. A median of 39% say they would stay the same.

Nigerians are the most likely to say policies would improve, with about two-thirds holding this view. More than 50% think the same in India, Indonesia and Kenya.

In contrast, significant shares of the public in several high-income nations believe policies would get worse if more elected officials were religious, including roughly half or more in Australia, France, Japan and Sweden.

Factors impacting views on electing more people who are religious

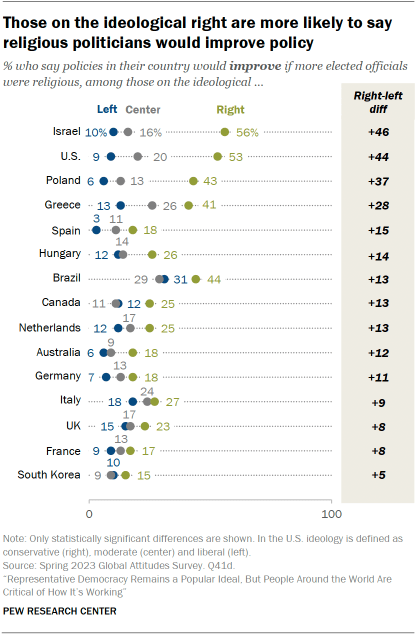

Ideology: Gaps exist in 15 of the 18 countries where we measure respondents’ ideology. In all 15 countries, those on the right are more likely than those on the left to say policies would improve if more elected officials were religious. The difference is most notable in Israel, Poland and the U.S.

Income: In 17 of 24 countries surveyed, people with lower incomes are somewhat more likely than those with higher incomes to suggest that electing more religious people would improve policies.

Education: In 15 countries, those with less education are more likely than those with more education to believe that having more religious people in office would yield positive results.

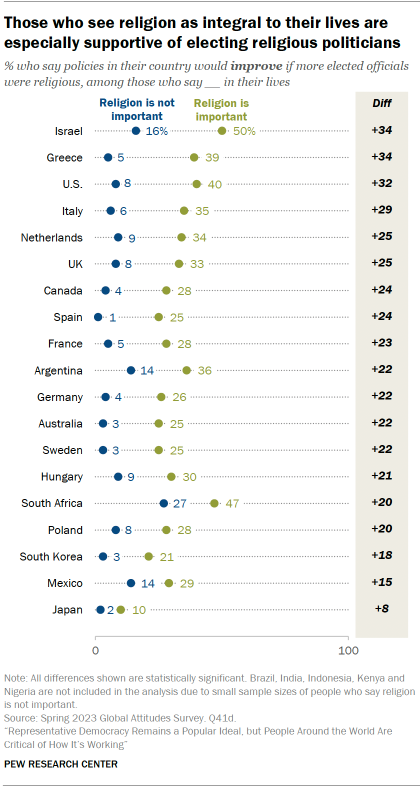

Religiosity: In nearly every nation polled, those who say religion is important in their lives are much more likely to say policies would improve if more politicians were religious.

For instance, in Greece, among those who say religion is important to them, 39% say policies would improve. Only 5% expect policies to improve among Greeks who say religion is not important to them.

Still, in most countries, even among those who say religion is important, relatively few think policies would improve if more people in office were religious.