Fewer have confidence in Biden to handle U.S.-China relationship than other foreign policy issues

Pew Research Center conducted this study to understand American views toward China. For this analysis, we surveyed 2,596 U.S. adults from Feb. 1 to 7, 2021. Everyone who took part in this survey is a member of the Center’s American Trends Panel (ATP), an online survey panel that is recruited through national, random sampling of residential addresses. This way nearly all U.S. adults have a chance of selection. The survey is weighted to be representative of the U.S. adult population by gender, race, ethnicity, partisan affiliation, education and other categories. Read more about the ATP’s methodology.

While Pew Research Center has been tracking attitudes toward China since 2005, prior to 2020, most of this work was done using nationally representative phone surveys. As a result, some long-standing trends may not appear in this report and others will indicate the shift in mode in the text and graphics, as appropriate. (For details on this shift and what it means for key measures of U.S. favorability toward China, see “What different survey modes and question types can tell us about Americans’ views of China.”)

We also draw on an open-ended question: “We’d like to learn a little bit about what you think about when you think about China. Please share the first things that come to mind when you think about China.” To analyze this question, we hand-coded 2,010 responses using a researcher-developed codebook. For more on this particular question, see “In their own words: What Americans think about China.”

Here are the questions used for the report, along with responses and survey methodology.

President Joe Biden has inherited a complicated U.S.-China relationship that includes a trade war, mutually imposed sanctions on high-ranking officials, tensions flaring over human rights issues, Hong Kong and Taiwan, and an American public with deeply negative feelings toward China.

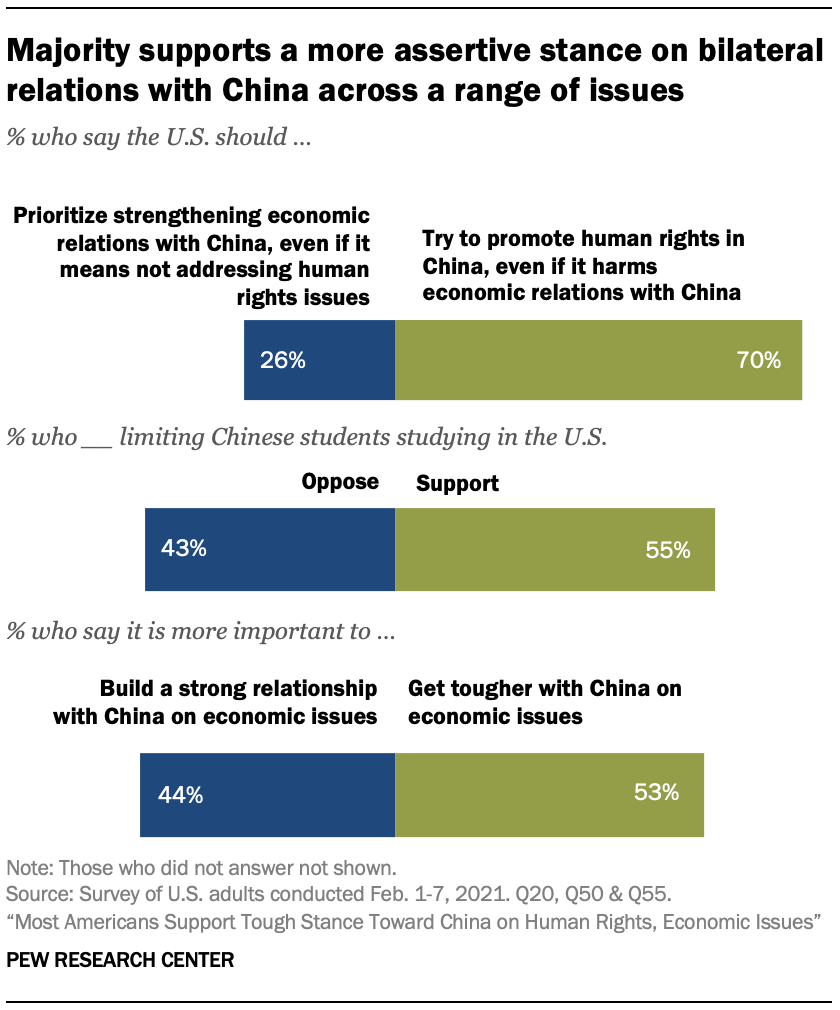

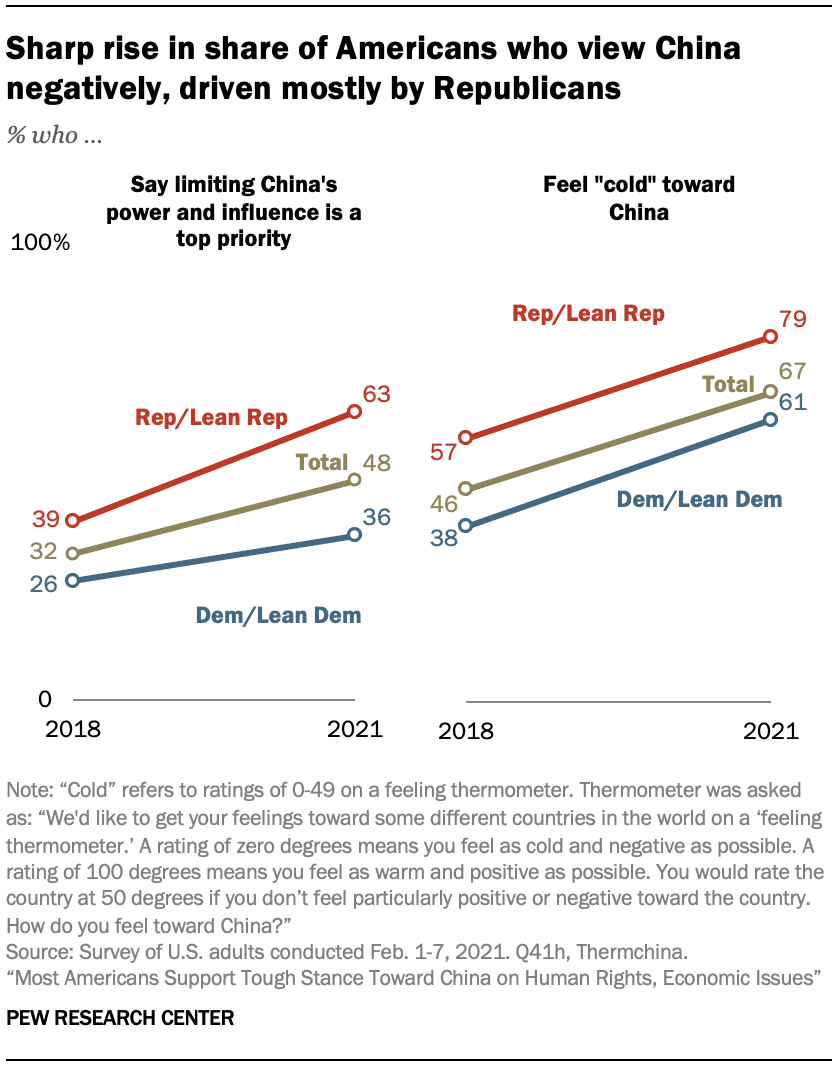

Roughly nine-in-ten U.S. adults (89%) consider China a competitor or enemy, rather than a partner, according to a new Pew Research Center survey. Many also support taking a firmer approach to the bilateral relationship, whether by promoting human rights in China, getting tougher on China economically or limiting Chinese students studying abroad in the United States. More broadly, 48% think limiting China’s power and influence should be a top foreign policy priority for the U.S., up from 32% in 2018.

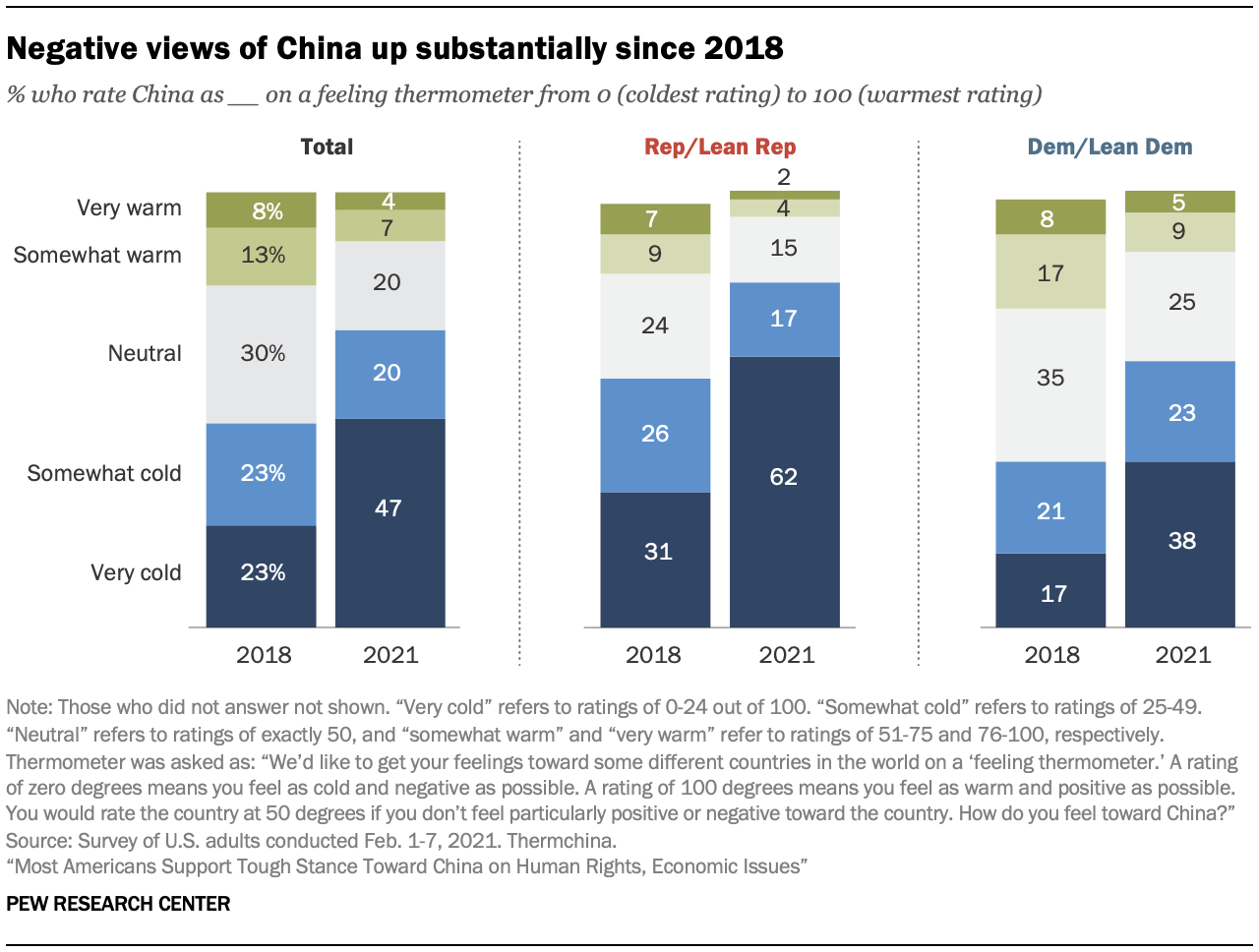

Today, 67% of Americans have “cold” feelings toward China on a “feeling thermometer,” giving the country a rating of less than 50 on a 0 to 100 scale. This is up from just 46% who said the same in 2018. The intensity of these negative feelings has also increased: The share who say they have “very cold” feelings toward China (0-24 on the same scale) has roughly doubled from 23% to 47%.

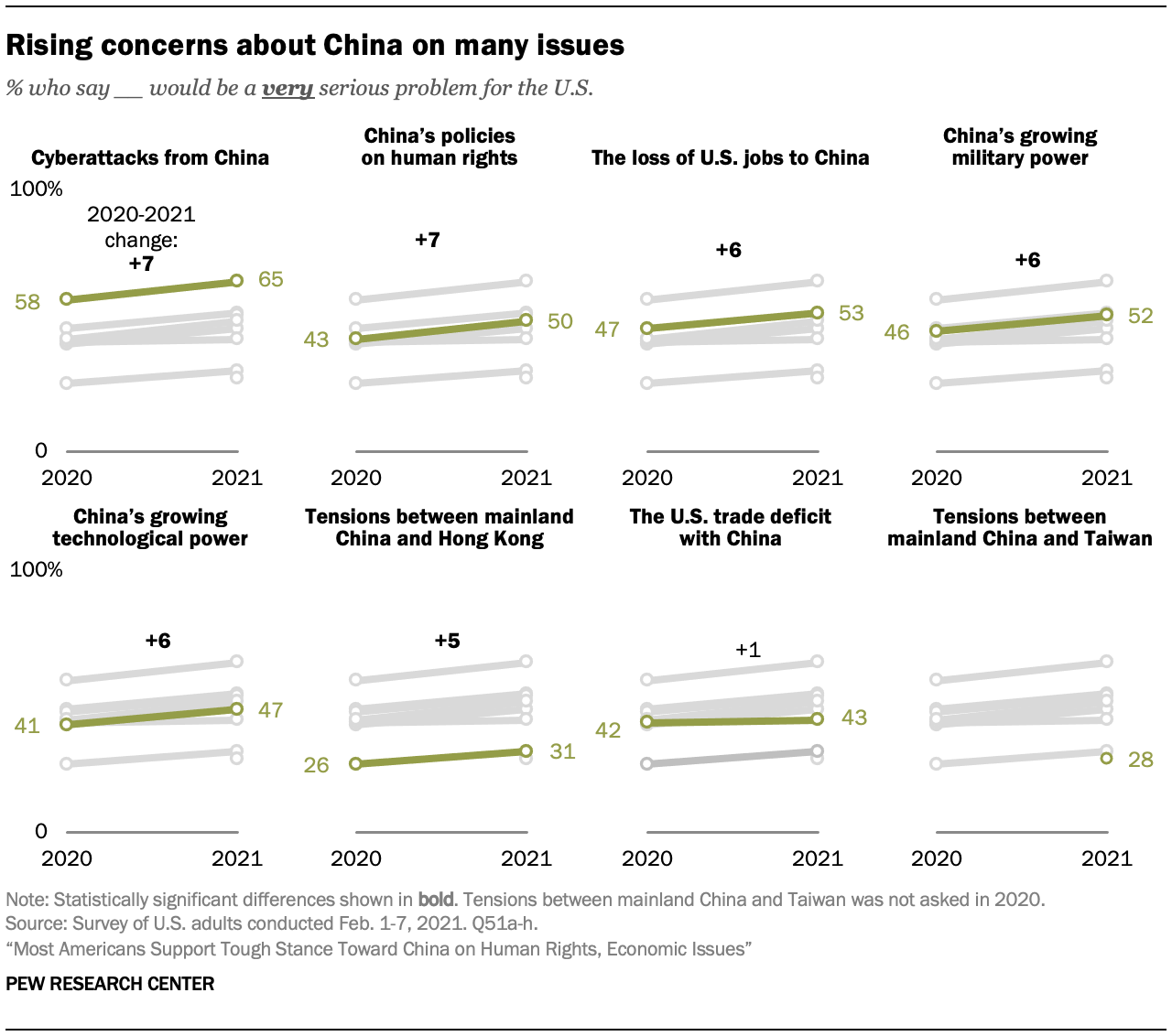

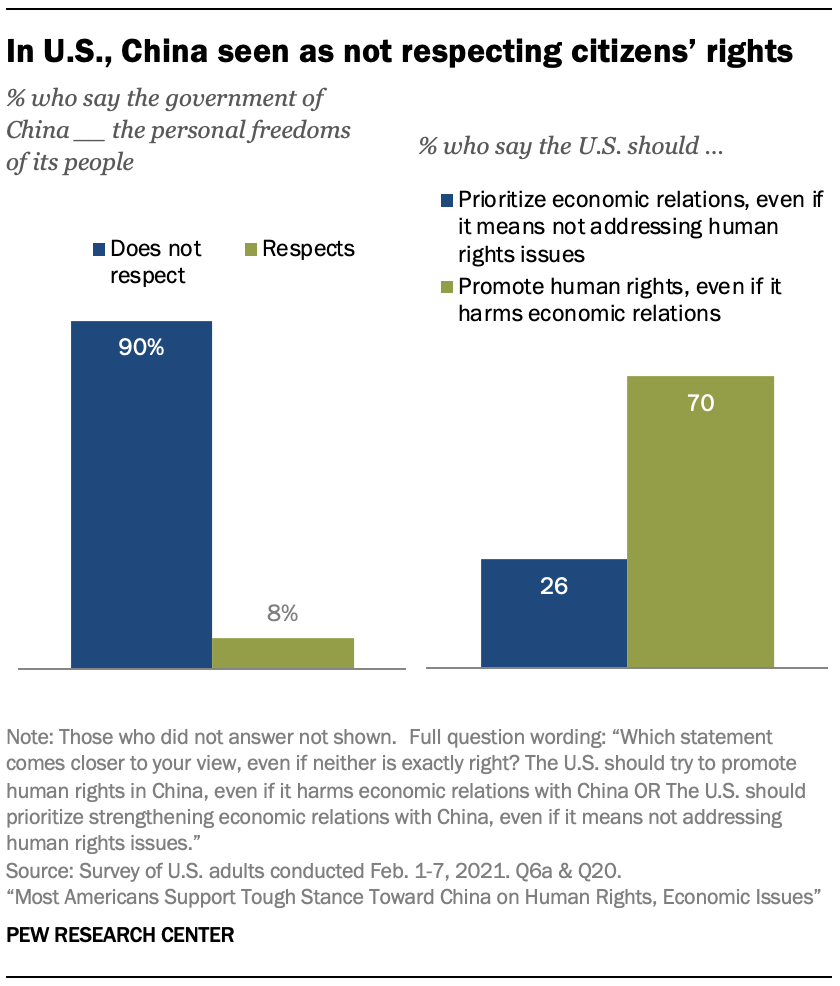

Americans have many specific concerns when it comes to China, and the sense that certain issues in the bilateral relationship – including cyberattacks, job losses to China, and China’s growing technological power – are major problems has grown over the past year alone. Half of Americans now say China’s policy on human rights is a very serious problem for the U.S. – up 7 percentage points since last year. And nine-in-ten Americans say China does not respect the personal freedoms of its people.

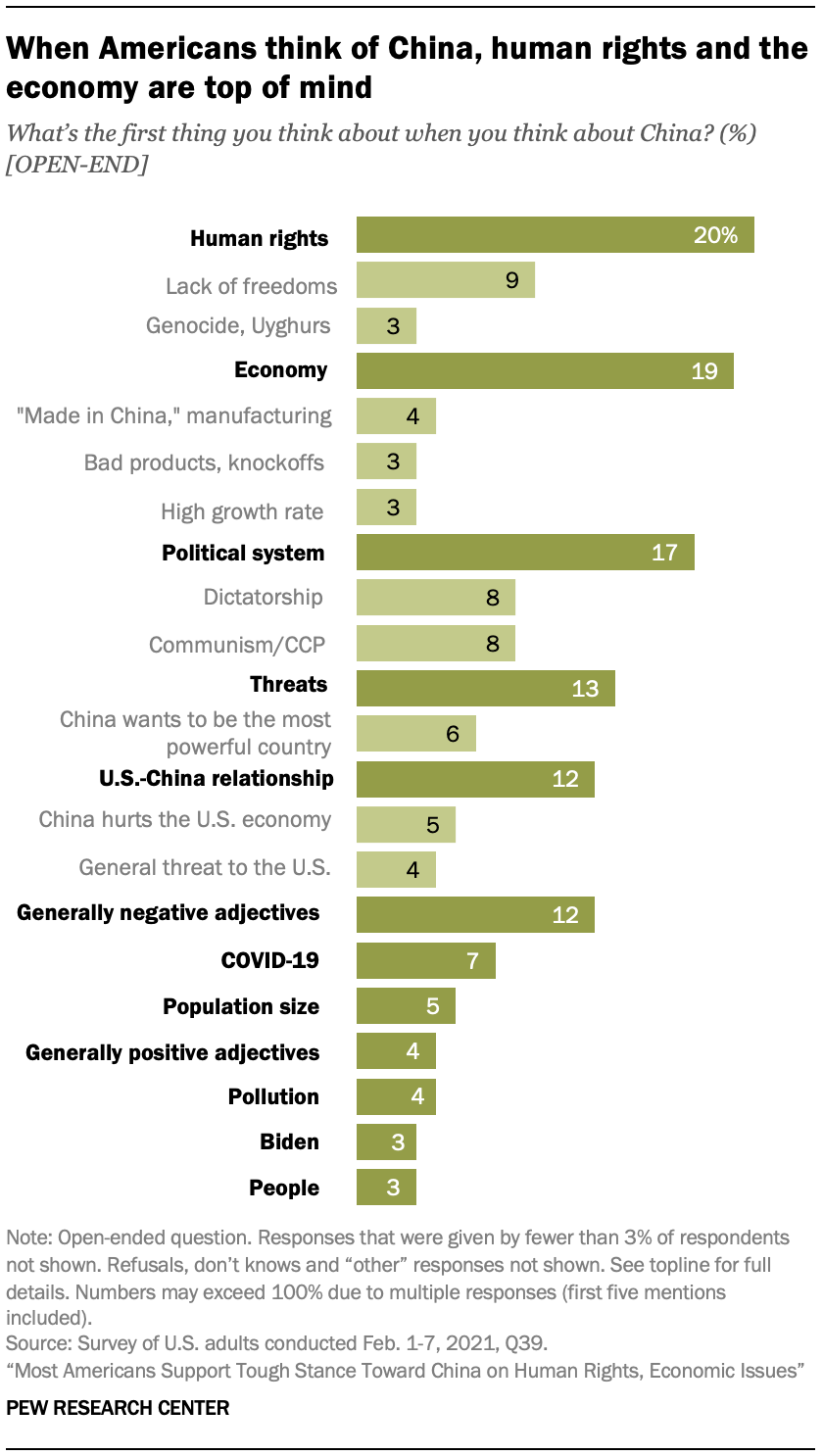

Human rights concerns also are frequently cited when Americans are asked, in an open-ended format, about the first thing that comes to mind when they think of China. One-in-five mention human rights concerns, with 3% specifically focused on Uyghurs in Xinjiang. (For more on the open-ended responses, as well as how they were coded, see “In their own words: What Americans think about China.” Quotations from this open-ended question appear throughout this report to provide context for the survey findings. They do not represent the opinion of all Americans on any given topic. They have been edited lightly for grammar and clarity.)

“The Chinese people as individuals are no different than other people, but their government is a totalitarian Communist regime bent on conquering its neighbors and land-grabbing, as shown by their takeover of Hong Kong.”

–Man, 52

Many also mentioned China’s powerful economy, its dominance as a manufacturing center – sometimes at the expense of the environment or workers – and issues related to the U.S.-Chinese economic relationship. Overall, Americans see current economic ties with China as fraught: Around two-thirds (64%) describe economic relations between the superpowers as somewhat or very bad.

“Leader in technology. Makes a lot of cheap products. A possible threat.”

–Man, 54

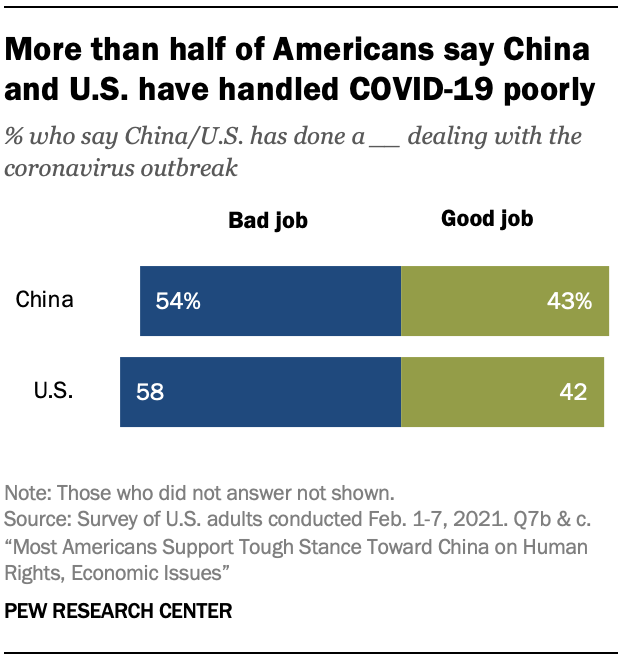

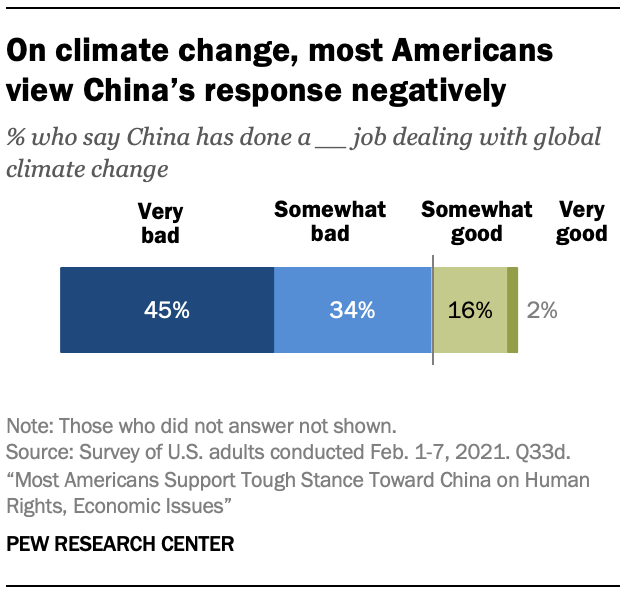

Americans are also critical of how China is dealing with some key issues. When it comes to dealing with global climate change, for example, a broad 79% majority thinks China is doing a bad job, including 45% who think it’s doing a very bad job. More Americans also think China is doing a bad job (54%) than a good one (43%) dealing with the coronavirus pandemic. Still, people are about as critical of America’s own handling of the pandemic (58% say it is doing a bad job).

As President Biden seeks to navigate this tumultuous relationship, few Americans put much stock in his Chinese counterpart, President Xi Jinping. Only 15% have confidence in Xi to do the right thing regarding world affairs, whereas 82% do not – including 43% who have no confidence in him at all.

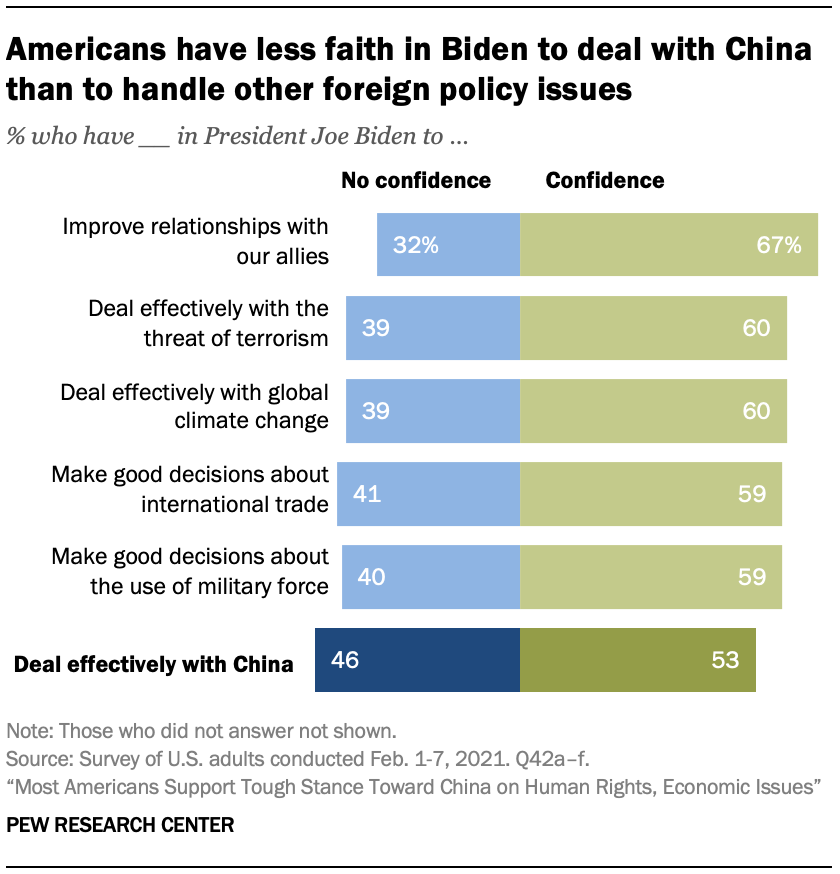

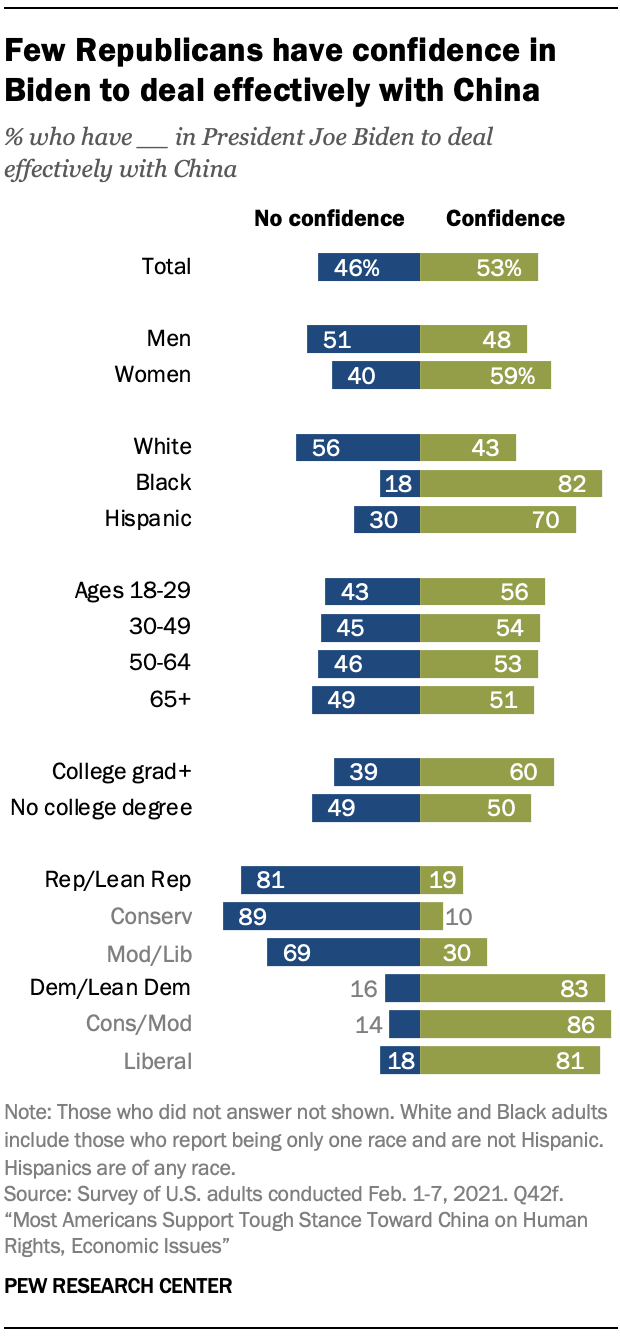

While 60% of Americans have confidence in Biden to do the right thing regarding world affairs in general, when it comes to dealing effectively with China, only 53% say they have confidence in him. This is fewer than say they have confidence in him to handle any of the other foreign policy issues asked about on the survey. Partisans are also worlds apart on this issue: 83% of Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents have confidence in Biden to deal effectively with China, compared with only 19% of Republicans and Republican leaners.

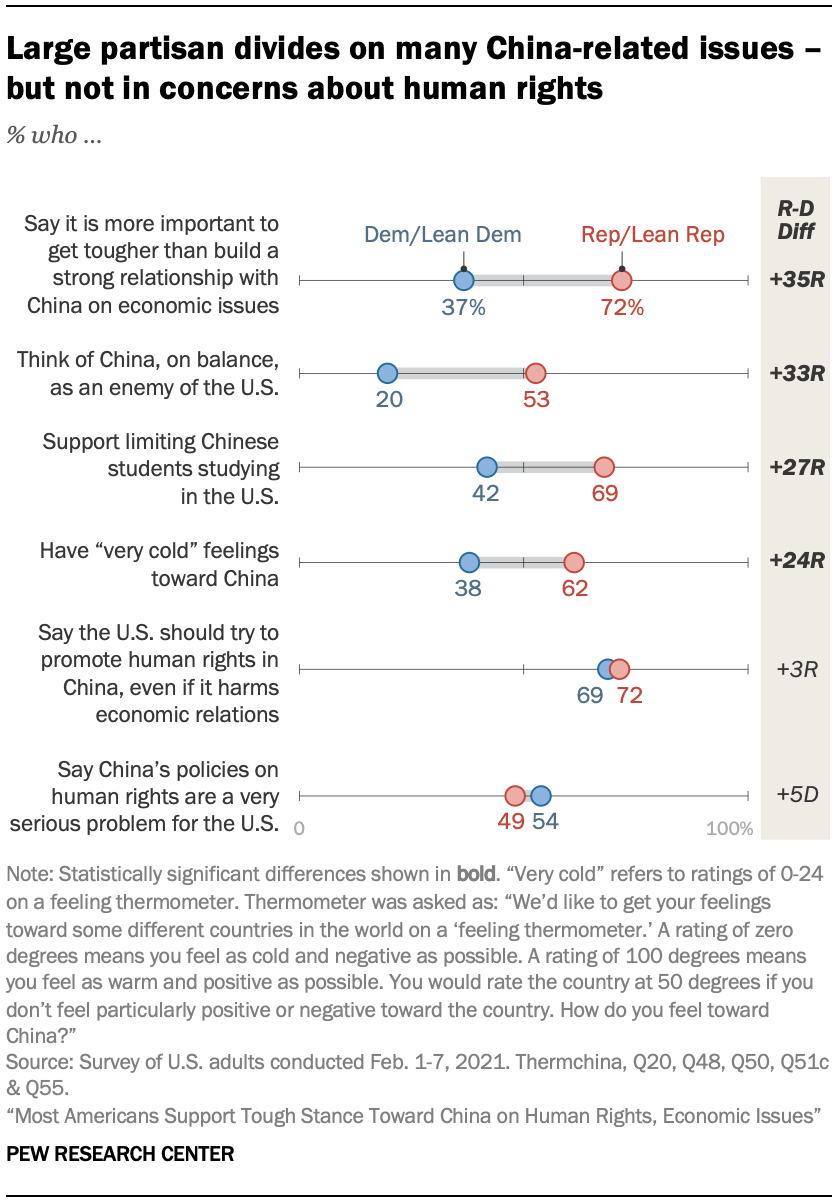

Many other issues related to China are also quite divided across party lines. Republicans are significantly more likely to say the U.S. should get tougher on China on economic issues (instead of trying to strengthen economic relations), to describe China as an enemy of the U.S. – rather than as competitor or partner – and to have very cold feelings toward China. They are also more likely to support limiting the ability of Chinese students to study in the U.S.

Republicans are also more likely than Democrats to describe most issues in the bilateral relationship as very serious problems for the U.S., including the loss of U.S. jobs to China (by 24 percentage points) and the U.S. trade deficit with China (19 points). The gap between the parties on these issues has grown over the past year, too, with Republicans increasingly describing these issues as very serious but Democratic opinion changing little.

Only on human rights-related issues – both the perception that China’s human rights policies are a major problem and support for promoting human rights in China – do Democrats and Republicans largely agree. The sense that China’s human rights policies are an issue in the bilateral relationship also increased a similar amount among both Republicans and Democrats over the past year.

These are among the findings of a new survey by Pew Research Center, conducted online Feb. 1-7 among 2,596 adults who are members of the nationally representative American Trends Panel.

Growing share of Americans express cold feelings toward China

A majority of Americans have negative feelings toward China, up substantially since 2018. Respondents indicated their feelings using a “feeling thermometer” where a rating of zero degrees means they feel as cold and negative as possible, a rating of 100 degrees means they feel as warm and positive as possible, and a rating of 50 degrees means they don’t feel particularly positively or negatively toward China. Based on this, 67% of Americans today feel “cold” toward China (a rating of 0 to 49). This is up 21 percentage points from the 46% who said the same in 2018.

Nearly half (47%) of Americans feel “very cold” toward China – rating it below 25 on the same 100-point scale – which is around twice as many as said the same in 2018 (23%). Similarly, the share of Americans who give China the lowest possible rating of zero has nearly tripled, from 9% in 2018 to around a quarter (24%) in 2021.

Only 7% of Americans have “warm” feelings (51-75) toward China and even fewer (4%) say they have “very warm” evaluations of the country (76-100). One-in-five Americans have neutral feelings toward the country, giving it a rating of exactly 50 on the thermometer.

While negative feelings toward China have increased among both Republicans and Democrats, the size of the partisan gap has also grown since 2018. Today, 62% of Republicans feel “very cold” (0-24) toward China – up 31 points since 2018. In comparison, 38% of Democrats report “very cold” feelings, up 21 points over the same period.

Since 2005, Pew Research Center has used telephone polling to measure Americans’ views of China as part of the Global Attitudes annual survey. Using the same four-point question each year, which asks people whether they have a “very favorable, somewhat favorable, somewhat unfavorable or very unfavorable view of China,” we have tracked the ups and downs in Americans’ views of the superpower, including the 26-point increase in negative views that has taken place since 2018.

Beginning this year, however, Pew Research Center has shifted to conducting the U.S. portion of its annual Global Attitudes survey using the American Trends Panel (ATP), a nationally representative online panel of adults that is the Center’s principal source of data for U.S. public opinion research. To prepare for this transition, we fielded two surveys simultaneously in early 2020 – one on the phone and one on the ATP – asking the same question about Americans’ favorability of China. Results indicated there were substantial differences by survey mode: 66% of those surveyed by phone had an unfavorable view of China, compared with 79% of those surveyed online.

Because of these mode differences, we fielded two different survey questions on the ATP this year. The first is a “feeling thermometer,” which asks people to evaluate their opinion of China on a 0 to 100 scale, where a rating of 51 or higher is “warm,” 50 is neutral and below 50 is “cold.” This question, which is the predominant focus of this report, was previously asked on the ATP in 2018 and 2016. Looking at these three points in time, we can see that the sharp increase in negative views of China that we have been documenting via our phone surveys is also evident via these online surveys. On this measure, those who say they are “cold” (0-49) toward China has increased from 46% in 2018 to 67% in 2021, or 21 percentage points.

Second, we also asked our traditional four-point favorability question. Because of the mode differences previously identified, we decided that this number from the online survey was not directly comparable to the phone surveys previously conducted. But we want to “restart” this trend, beginning to measure it consistently on the ATP going forward, much as we have done so on the phone for the past 15 years. Results of this question indicate that a majority of Americans (76%) have an unfavorable view of China. This is consistent with the majority who say they are “cool” toward China on the feeling thermometer rating, though there are differences due, in part, to the fact that the feeling thermometer has an explicit “neutral” category. (For more on how these two measures are similar and different, see “What different survey modes and question types can tell us about Americans’ views of China.”)

Thanks to these two questions, we can see that unfavorable views of China increased dramatically since 2018, regardless of mode (phone vs. online) or measure (feeling thermometer or four-point scale).

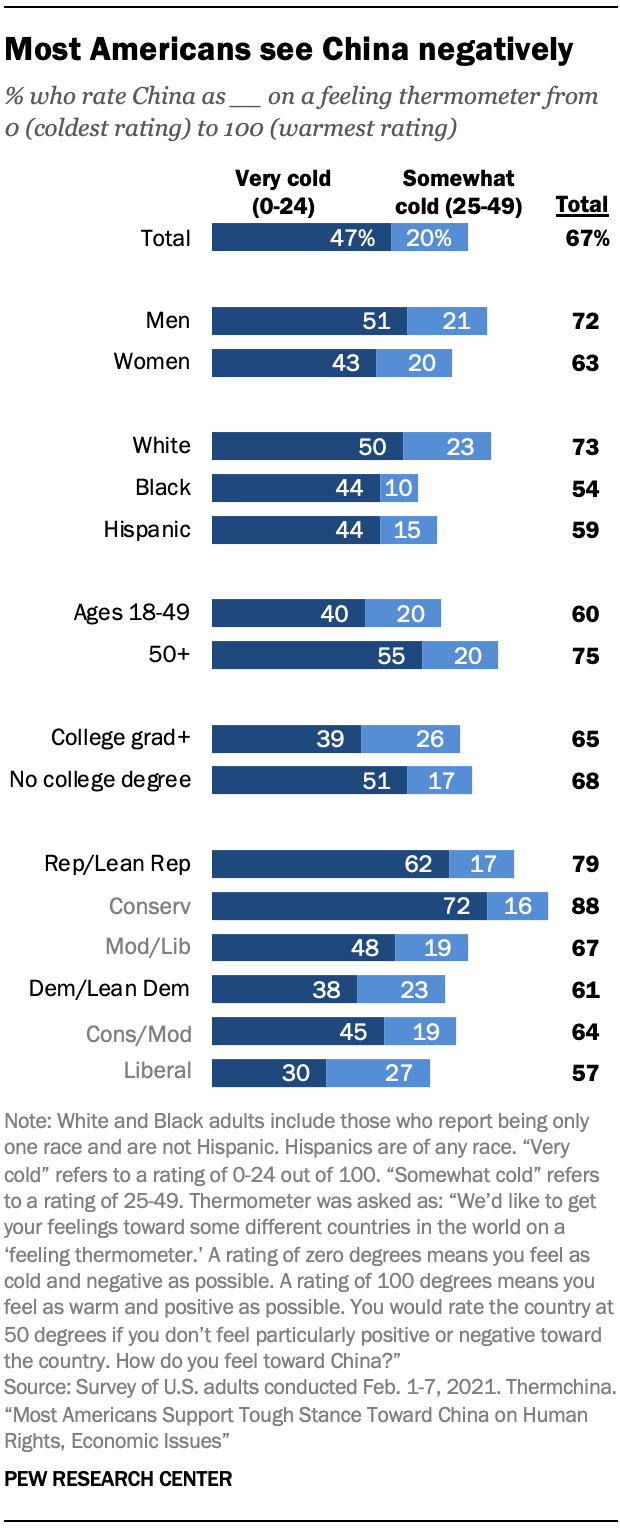

Conservative Republicans are even more likely to say they have “very cold” feelings toward China (72%) than moderate or liberal Republicans (48%). Among Democrats, conservatives and moderates (45%) are more likely than liberals (30%) to have very cold feelings toward China.

Men (51%) are more likely than women (43%) to have “very cold” feelings toward China. A majority of those 50 and older (55%) have “very cold” opinions of China, whereas only 40% of those under 50 report the same. Americans with lower levels of education are more likely to feel “very cold” toward China: 51% of those who have not completed college feel this way, compared with 39% of those with at least a bachelor’s degree.

While most Americans have unfavorable views toward China, results of an open-ended question about China indicate that opinions can be multifaceted. Even among those who say have “cold” feelings toward China, there are instances where people report good and bad things.

“I think about the human rights abuses, such as the indefensible treatment of the Uyghurs, as well as the infringements of personal freedoms suffered by all citizens. I think about the gender imbalances still present from the one-child laws of the past, which further harms their society. I [also] think about the centuries of rich culture and history that created incredible art and architecture, as well as incredible inventions that furthered humanity as a whole.”

–Woman, 35

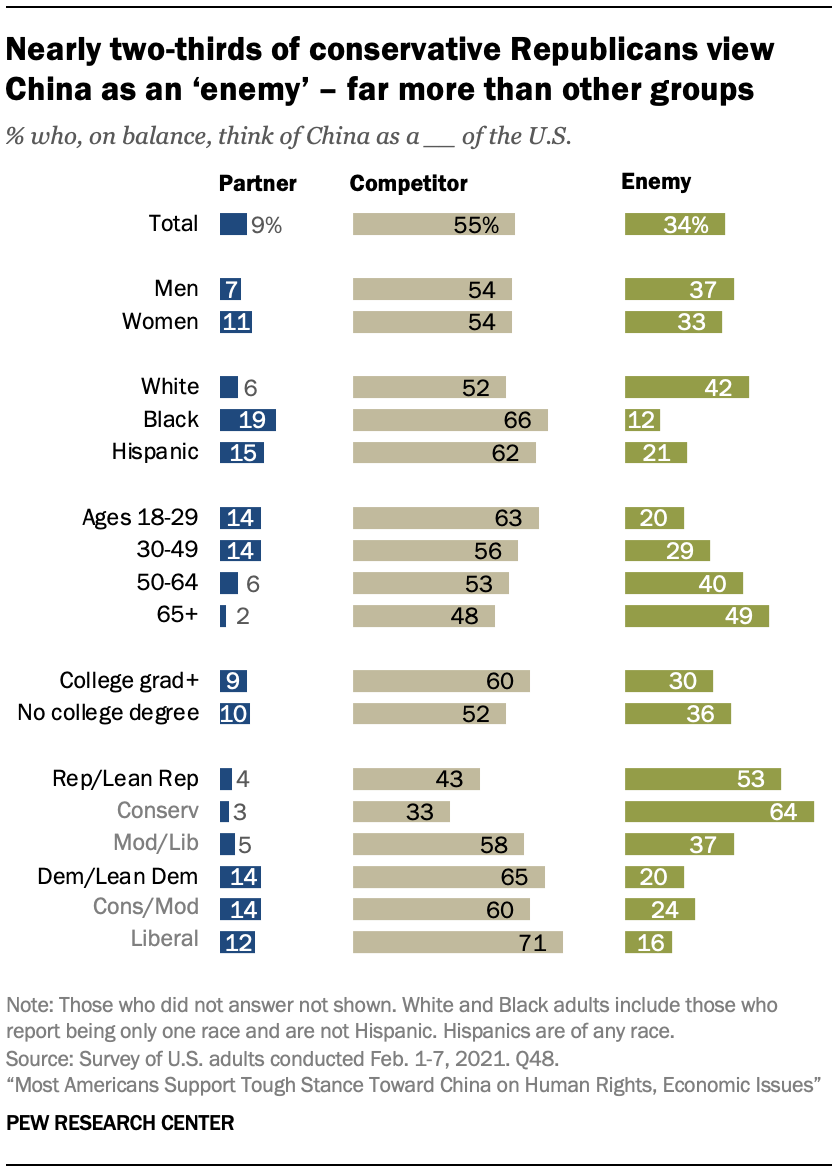

Republicans are much more likely to describe China as enemy of the U.S.

A majority of Americans describe China as a competitor (55%) rather than as an enemy (34%) or a partner (9%).

Partisans differ substantially in their evaluations of the U.S.-China relationship. Whereas 53% of Republicans and independents who lean toward the Republican Party describe China as an enemy, only 20% of Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents say the same. Nearly two-thirds of conservative Republicans say China is an enemy (64%), while only 37% of moderate or liberal Republicans say the same.

While Democrats are more likely than Republicans to describe China as a partner, they are also more likely to describe it as a competitor, with nearly two-thirds of Democrats and Democratic leaners (65%) describing the relationship in this way.

Black, White and Hispanic adults also differ in their evaluations of the U.S.-China relationship. Whites are significantly more likely than Hispanic (21%) or Black adults (12%) to describe China as an enemy (42%). White Americans are also much less likely to describe China as a partner (6%) than are Black (19%) or Hispanic (15%) Americans.

“Powerful U.S. competitor on world stage and long-term frenemy …”

–Man, 51

Older adults, too, are significantly more likely than younger ones to describe China as an enemy. Whereas around half (49%) of those ages 65 and older say that China is an enemy, only 20% of those under 30 say the same. Those who have not completed college are somewhat more likely than those who have a college degree to describe China as an enemy (36% vs. 30%, respectively).

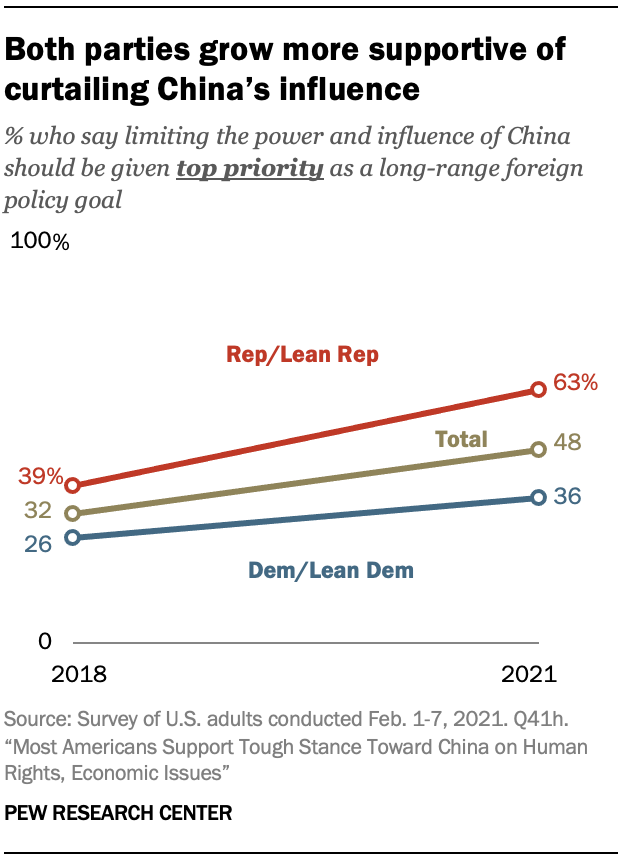

Americans increasingly prioritize limiting China’s power and influence

Nearly half of Americans (48%) think limiting the power and influence of China should be a top foreign policy priority for the country, and another 44% think that it should be given some priority. Only 7% think limiting China’s influence should not be a priority at all. The share of Americans who think limiting China’s power and influence should be a top priority is also up 16 percentage points since 2018.

Republicans are much more likely than Democrats to say limiting China’s power and influence is a top priority (63% vs. 36%, respectively). Conservative Republicans (68%) are even more likely than moderate or liberal Republicans to say this (54%). And, while support for limiting China’s influence has increased since 2018 among both Republicans and Democrats, the rise has been especially steep among Republicans.

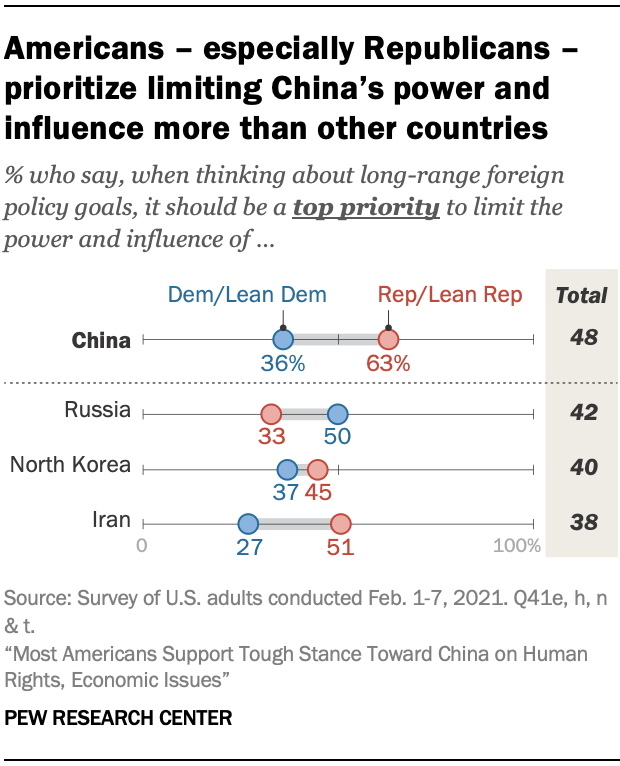

Limiting China’s power and influence is one of the top priorities cited by Americans among 20 foreign policy goals asked about in the survey. The only issues of the 20 tested that are named as a top priority by more Americans are protecting the jobs of American workers (75%), reducing the spread of infectious diseases (71%), taking measures to protect the U.S. from terrorist attacks (71%), preventing the spread of weapons of mass destruction (64%) and improving relationships with our allies (55%). And, when it comes to comparisons with other countries, more Americans see limiting China’s power and influence as a top priority than say the same of Russia (42%), North Korea (40%) or Iran (38%).

Still, there are major partisan differences with regard to the relative importance of limiting China’s power and influence. For Republicans, it is the fifth most important issue of the 20 tested, while for Democrats, it ranks 12th.

The 27-point gap between Republicans and Democrats when it comes to whether limiting China’s power and influence is a top priority is one of the largest partisan gaps across the 20 issues tested. The only more divisive issues are dealing with global climate change (Democrats 56 points more likely to name this), reducing illegal immigration into the U.S. (48 points higher among Republicans), and maintaining the U.S. military advantage over all other countries (Republicans 38 points more likely).

Older Americans are more likely to say limiting China’s power and influence should be a top priority: 58% of those ages 50 and older say this, compared with 39% of those under 50. Those with lower levels of education are also more likely to call limiting China a top priority: 50% of those who have not completed a bachelor’s degree compared with 43% of those who have.

“I personally fear China’s powers more than any other country.”

–Woman, 80

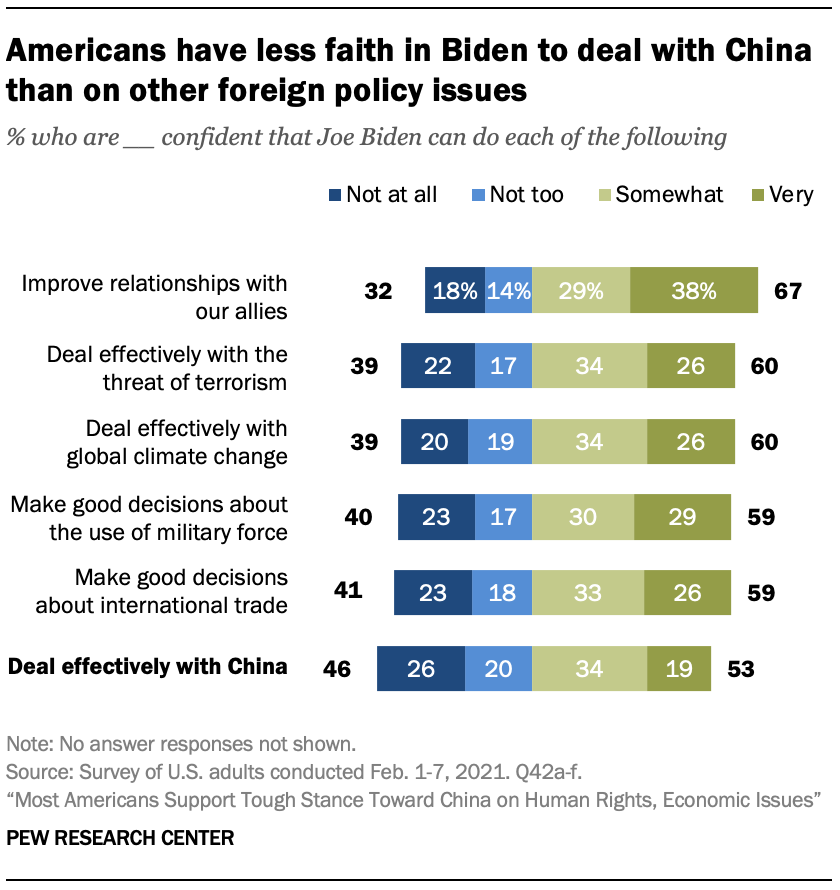

Partisans sharply divided over confidence in Biden to deal with China

Around half of Americans have confidence Biden will be able to deal effectively with China (53%). Still, this is the issue among six tested in which Americans have the least confidence in Biden. For example, 67% have confidence in him to improve relationships with allies, and around six-in-ten say they think he will be able to deal effectively with the threat of terrorism and global climate change, as well as to make good decisions about the use of military force and international trade.

Women (59%) are more confident than men (48%) in Biden’s ability to deal effectively with China. Black (82%) and Hispanic adults (70%) also express more confidence than White adults (43%). Those with a college degree expect Biden will be able to deal effectively with China at a higher rate than those with less schooling (60% vs. 50%, respectively).

Partisan differences are particularly large. Whereas 83% of Democrats and leaners toward the Democratic Party have confidence in Biden on China, only 19% of Republicans and leaners say the same. Conservative Republicans have even less confidence (10%) than moderate or liberal Republicans (30%), though conservative and moderate Democrats (86%) are about as confident in Biden on dealing with China as liberal Democrats (81%).

Americans anxious about China’s technological and military power

Americans express substantial concern when asked about eight specific issues in the U.S.-China relationship. About three-quarters or more say that each issue is at least somewhat serious. Still, four problems stand out for being ones that half or more describe as very serious: cyberattacks from China, the loss of U.S. jobs to China, China’s growing military power and China’s policies on human rights.

Cyberattacks from China evoke the most concern: Roughly two-thirds consider digital attacks to be a very serious problem. This is a 7 percentage point increase from 2020.

The share who see the loss of U.S. jobs to China as a very serious problem has increased by 6 points since 2020, to 53%. A similar share sees China’s growing military power as a very serious problem (largely unchanged from the 49% who said the same last year).

China’s policies on human rights are seen as a very substantial problem for the U.S. by half of American adults, a 7-point increase since 2020. China’s treatment of Uyghurs in Xinjiang was recently labeled a “genocide” by former U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo. Results of previous telephone polls indicate that concerns about China’s human rights policies increased between 2018 and 2020 as well.

About four-in-ten Americans see the U.S. trade deficit with China – which decreased for the second year in a row – as a very serious problem, unchanged from 2020. Those with less than a college degree are more likely than those with a college degree or more education to see the trade deficit with China as a very serious problem. Similarly, those with lower levels of education are more likely to call the loss of U.S. jobs to China a very serious problem – but when it comes to other problems, people with different educational attainment levels largely agree.

Tensions between mainland China and Hong Kong or Taiwan are seen as less serious problems for most Americans. While about three-quarters say these two geopolitical issues are at least somewhat serious problems, only about three-in-ten say they are very serious. Still, the share who see Hong Kong’s tensions with mainland China as a very serious problem has increased by 5 percentage points since last year. (Last year’s survey did not ask about tensions between mainland China and Taiwan.)

“They are actively working to take over the U.S. economically rather than militarily. They are pulling our manufacturing abilities, copying advanced technologies, buying up large-scale U.S. corporations and they own much of our debt. They are methodically taking over control of our economy.”

–Man, 82

Across age groups, older Americans express more concern about China-related issues. Americans ages 65 and older are at least 20 points more likely than those ages 18 to 29 to say most issues asked about in the survey are very serious problems.

Republicans and Republican-leaning independents tend to be more concerned about most of these eight bilateral issues than Democrats and Democratic leaners. And conservative Republicans are particularly likely to call most of these issues very serious problems for the U.S. For example, 73% of conservative Republicans see the loss of U.S. jobs to China as a very serious problem, while only 55% of moderate or liberal Republicans agree.

When it comes to China’s human rights policies and tensions between Taiwan and mainland China, however, partisans largely agree. Compared with 2020, concern about various China-related issues generally increased more among Republicans than among Democrats. For instance, while the share of Republicans who say the loss of U.S. jobs to China poses a very serious problem increased by 14 percentage points, there was no significant change among Democrats. On issues where concern rose overall, increases tended to be especially steep among conservative Republicans.

China’s handling of coronavirus and climate

More than a year after the coronavirus became a widespread public health issue in the U.S., more than half of Americans say China has done a bad job dealing with the outbreak (54%). Around a quarter (28%) even think China’s pandemic response has been very bad.

Just 43% think China has done a good job dealing with the coronavirus outbreak, with only 12% saying China has done a very good job.

And, while more Americans say China has done a bad job than a good job dealing with the pandemic, they are just as critical of the U.S.’s handling of the pandemic, which 58% describe as bad.

Republicans (71%) are much more likely than Democrats (39%) to see China as having done a bad job with the COVID-19 outbreak. Those with less than a college degree are more likely to say China has done a bad job compared with those have at least a bachelor’s. White Americans also give China worse ratings than do Black or Hispanic Americans.

“China is the origin country for COVID-19 but they managed to keep the virus from spreading further, way better than the U.S.”

–Woman, 30

One area where Americans think China could do much more is climate change. The world’s largest contributor of carbon emissions, China has pledged to become carbon neutral by 2060 while still espousing its right to develop. By a nearly four-to-one ratio, Americans think China has done a bad job handling climate change, with 45% saying China has done a very bad job. On the other hand, just 2% think China’s approach to global warming thus far has been very good. No more than a quarter rate China’s climate change approach positively regardless of age, education or political affiliation.

Americans want to prioritize human rights in U.S.-China relations

Human Rights Watch called 2020 “the darkest period for human rights in China” since the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests. Amid crackdowns in Hong Kong, continued persecution of ethnic minorities such as the Muslim Uyghur population and detaining dissidents, Americans, too, have taken notice. Fully 90% of adults in the U.S. say the Chinese government does not respect the personal freedoms of its people. This perspective is shared among large majorities of Americans across age, education and political groups.

And Americans want more focus on human rights – even at the expense of economic ties – in bilateral relations with China. When asked whether the U.S. should prioritize economic relations with China or promote human rights in China, 70% of Americans choose human rights, even if it potentially harms economic relations with China.

About seven-in-ten Democrats and Republicans say the U.S. should promote human rights in China, even if it harms economic relations between the two countries. Among Republicans, those who identify as conservative Republicans are more likely than their moderate or liberal counterparts to hold this opinion. Among Democrats, those who identify as liberal are the most likely to emphasize human rights over economic dealings in U.S.-China relations.

“When I think of China, the first thing that comes to mind is the oppressive measures it takes on those within its borders, especially the plight of Uyghur Muslims, but also the restrictions placed by the Communist government on free speech and dissent by its citizens. After that, America’s weakening role as a superpower in global competition against China comes to mind.”

–Man, 30

Americans favor tougher stance on China economic policies, question efficacy of tariffs

Targeted tariffs and increased intellectual property scrutiny set the backdrop of the U.S.-China trade war and the bilateral economic relationship during the four years of the Trump administration. While President Biden has indicated he would change tack in bilateral economic dealings, he has also described China as America’s “most serious competitor” and has kept some Trump-era China policies in place, at least for now.

Americans, too, see a precarious economic relationship between the two nations: 64% believe current economic relations between the U.S. and China are bad. Among those who say economic relations are good, just 1% say they are very good. (Results of a similar question asked on the phone indicates that Americans increasingly saw bilateral economic ties to be in poor shape over the course of the trade war.)

“I work in tech and my company does a lot of business in China. The trade war and bans on sales to certain companies have hurt our business and seem arbitrary. I have been to China many times. I don’t agree with all of China’s policies but I also don’t agree with how the U.S. government has managed its relationship under Trump.”

–Woman, 49

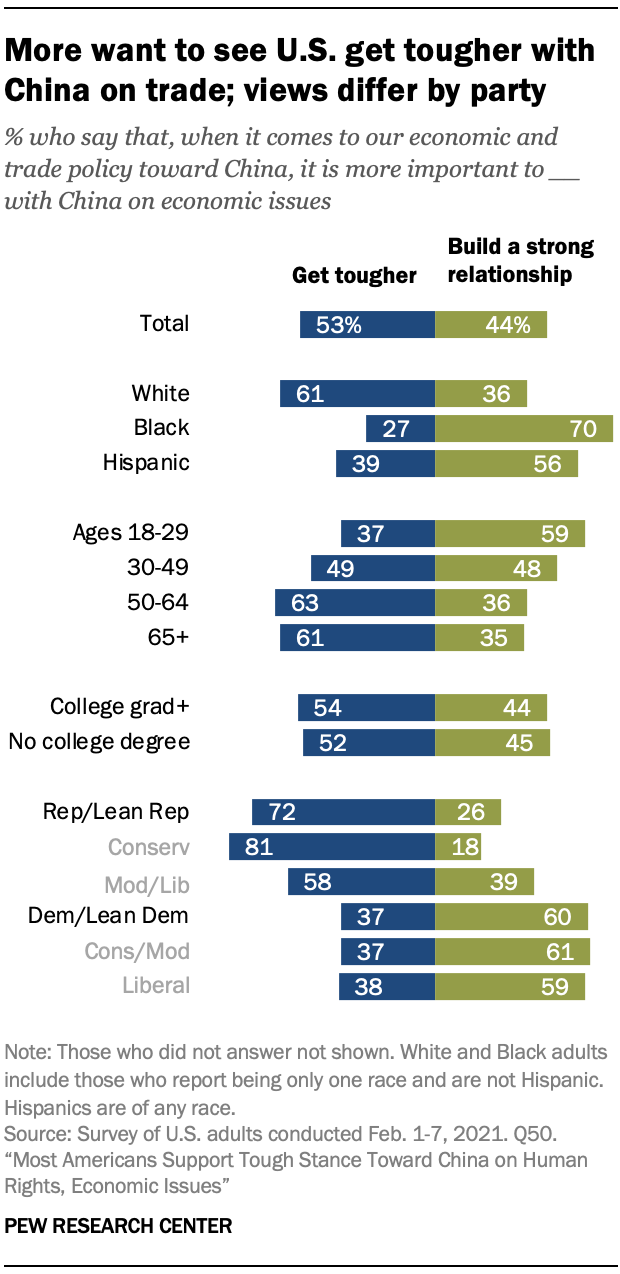

When thinking about economic and trade policies with China, more Americans want the U.S. to get tougher with China rather than to focus on building a stronger relationship. This opinion is particularly prevalent among Republicans and Republican-leaning independents (72% of whom want the U.S. to get tougher on China), and especially among those who identify as conservative Republicans (81% of whom say the same). About six-in-ten Democrats and Democrat-leaning independents would rather focus on building stronger ties with China, a feeling that is largely consistent among liberal and more moderate or conservative Democrats.

Younger people – those ages 18 to 29 – are also more likely than their older counterparts to stress building a stronger relationship with China over getting tougher with Beijing.

“I think China has grown too big. That normally wouldn’t be a problem but some of the things they have done lately is concerning to me. I don’t like that we owe them so much money. I don’t trust them anymore.”

–Woman, 57

Part of the Trump administration’s trade policy with China involved imposing tariffs on steel, aluminum and assorted other goods from China in the name of national security and American manufacturing.

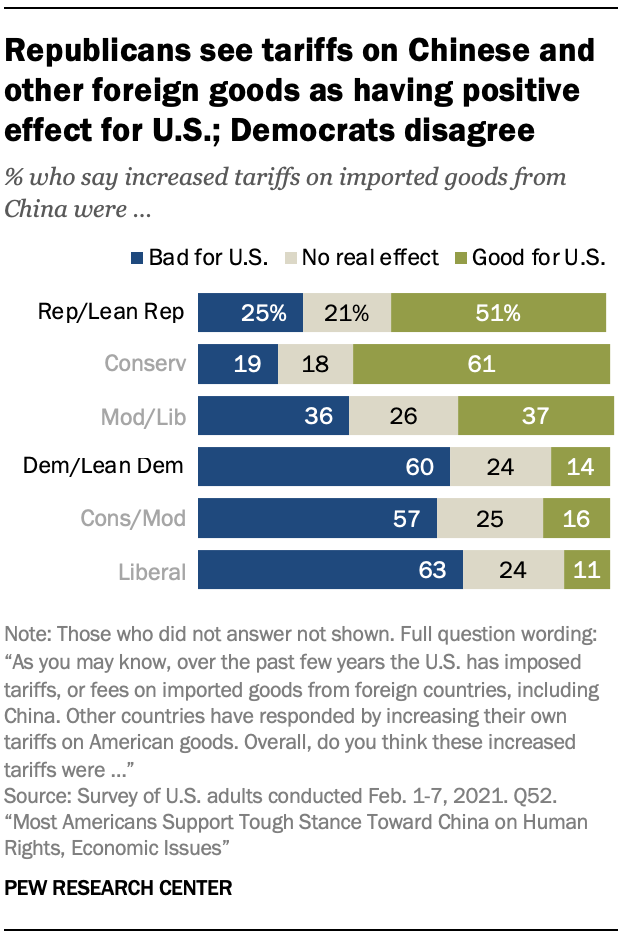

The U.S. public offers varied reviews of the tariff policies. When asked about the effects of increased tariffs on goods from foreign countries, including from China, more say they were ultimately bad for the U.S. (44%) than good (30%), while about a quarter of Americans think the tariffs had no discernable effect on the U.S. In terms of how the tariffs affected their own life personally, a majority say they had no real effect on them. Opinions on the tariffs’ personal effects differ little based on people’s own incomes or where they are located geographically in the country.

Some partisan differences arise, especially when assessing how tariffs affect the country overall. About half of Republicans say increased tariffs on Chinese and other foreign products were good for the U.S. This sentiment is especially strong among conservative Republicans. Republicans who identify as moderate or liberal are divided, with nearly equal shares describing the tariffs as good and bad. Democrats, on the other hand, most often say the tariffs were bad for the U.S.

Those who think that the U.S. economy is in good shape are more likely to describe the tariffs as good for the country than those who say the American economy is not doing well – 49% vs. 20%, respectively.

Americans generally welcome international pupils, but widespread support for limits on Chinese students

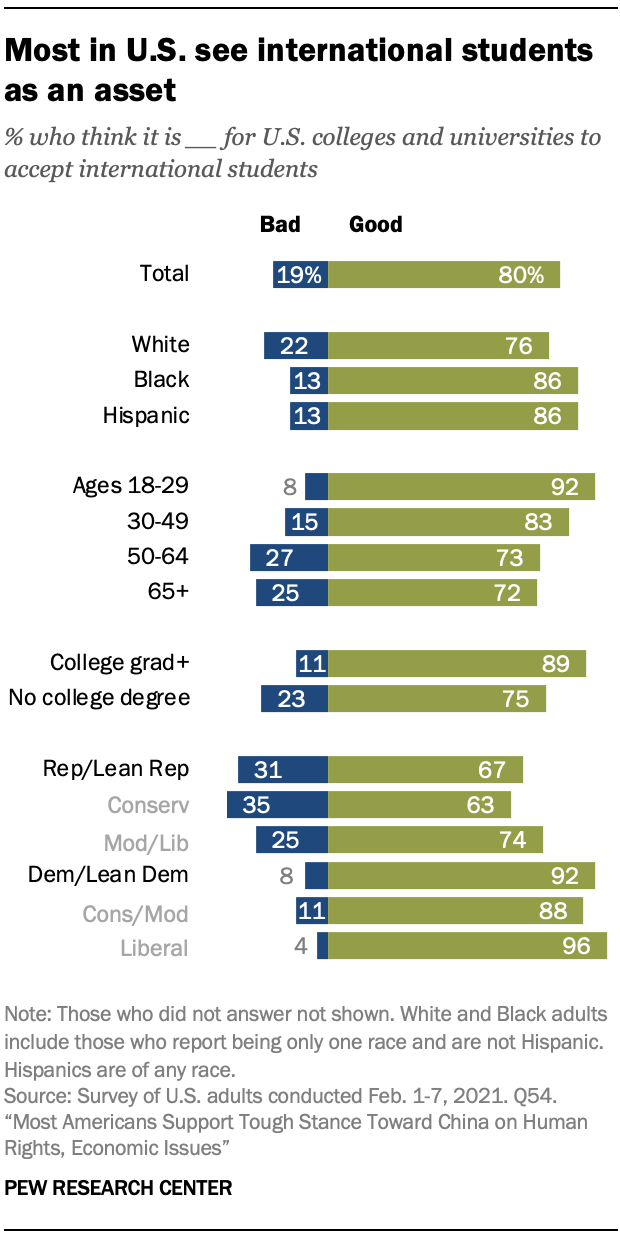

Although international student enrollment in the U.S. fell dramatically in 2020 because of COVID-19, during the 2019-202o school year, more than 1 million international students studied at U.S. colleges and universities, comprising 5.5% of all student enrollment in American tertiary education. And generally speaking, the U.S. public sees these students in a positive light: Eight-in-ten Americans say it is good for U.S. colleges and universities to accept international students, while just 19% think the opposite.

This sentiment is especially strong among certain subgroups in the U.S. population. Black and Hispanic Americans are more likely than White Americans to see international students as an asset. Likewise, younger people and those with a college degree say it is good for U.S. universities to accept international students. Partisanship also plays a role in views of international students. While at least two-thirds of supporters of each party see visiting students in a positive light, 92% of Democrats and Democrat-leaning independents hold this perspective, versus just 67% of Republicans and Republican leaners.

Since 2009, the largest share of international students in the U.S. have come from China, according to the Institute of International Education. In 2019-2020, Chinese students comprised roughly a third of international students in American colleges and universities, and the number of Chinese students in U.S. academic institutions had nearly tripled over the previous decade.

Yet, while the U.S. public generally welcomes international students, people are more divided when it comes specifically to Chinese students. A majority of Americans (55%) support limiting Chinese students studying in the U.S., including about one-in-five Americans who strongly support this idea. On the other hand, 43% oppose limitations on Chinese students, with 18% strongly opposed.

At least half of White, Black and Hispanic Americans would at least somewhat support limits on Chinese students in the U.S. Among those who have obtained a college degree, more oppose than support restricting the number of Chinese students at Americans institutions. A majority of those without a college degree are in favor.

Among Americans ages 50 and older, roughly seven-in-ten are in favor of limiting Chinese students. Those ages 30 to 49 are evenly split between support and opposition, while nearly two-thirds of Americans 18 to 29 oppose the idea. Republicans are also more likely than Democrats to favor limitations on the number of Chinese students attending U.S. college or universities.

“We rely TOO MUCH on goods from China. China is trying to dominate the whole world and we are supporting that with the stuff we buy from them. Too bad their scientists seem to be smarter than ours. And they are welcomed here as students. We have to stop kissing up to China.”

–Man, 79

Confidence in Xi stays low

When asked how much they trust Chinese President Xi Jinping to do the right thing regarding world affairs, roughly eight-in-ten Americans (82%) say they have little or no confidence in the Chinese leader. The share who say they have no confidence at all in Xi has increased by 5 percentage points from 38% last spring to 43%. Previously, levels of distrust in the Chinese president increased sharply after the coronavirus outbreak began.

Negative ratings for Xi are high across demographic and partisan groups, though there are a few modest differences. Men are somewhat more likely than women to distrust Xi, with half of American men saying they have no confidence at all in Xi. Half of White adults likewise say have no confidence at all in Xi. In comparison, 31% of Hispanic adults and 29% of Black adults hold the same opinion.

Across age groups, older Americans are more likely to have no confidence in the Chinese president. While 53% of those 65 and older say they have no confidence at all in Xi, only 35% of those 18 to 29 say the same.

“China is a country to be feared. Their leadership cannot be trusted. We should be harder on China in every way.”

–Man, 76

Among Republicans and Republican-leaning independents, a majority (57%) say they have no confidence at all in Xi. Conservative Republicans are nearly 20 points more likely than moderate or liberal Republicans to hold this view.

Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents have slightly more confidence in Xi; only a third say they have no confidence at all in the Chinese president. And, while conservative or moderate Democrats are the least likely to distrust Xi, a majority of them lack confidence in the Chinese president.