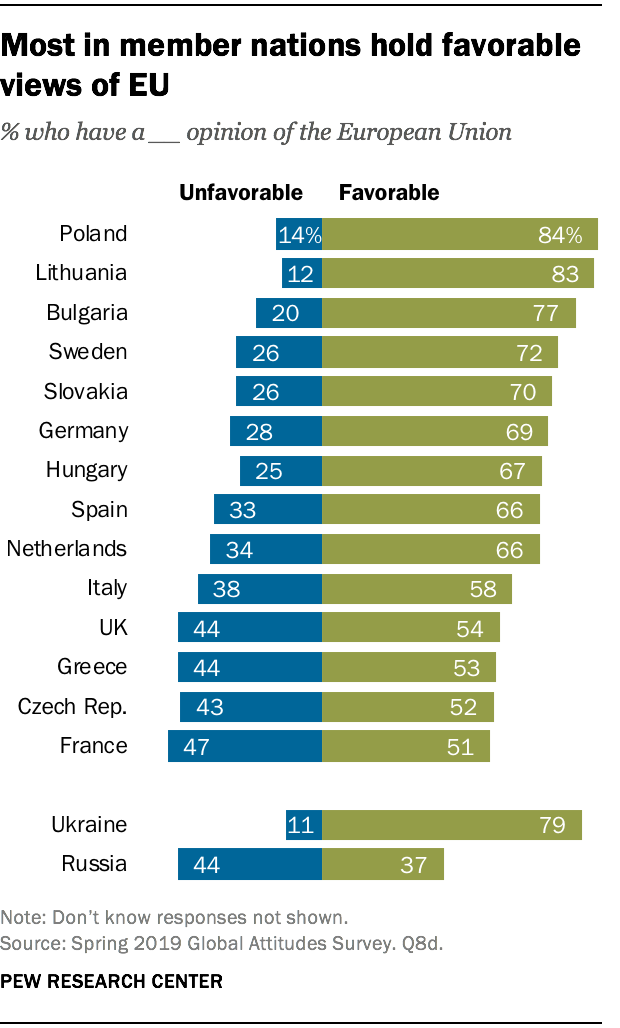

The European Union gets mostly favorable marks from the countries surveyed, but not everyone is happy with the Brussels-based institution. Across the 14 EU member countries surveyed, a median of 67% hold favorable views of the European Union while 31% have an unfavorable view.

The European Union gets mostly favorable marks from the countries surveyed, but not everyone is happy with the Brussels-based institution. Across the 14 EU member countries surveyed, a median of 67% hold favorable views of the European Union while 31% have an unfavorable view.

Many of the Central and Eastern European countries surveyed hold strongly positive views of the political union. Roughly seven-in-ten or more in Poland, Lithuania, Bulgaria, Slovakia and nonmember Ukraine give the EU favorable marks, including at least two-in-ten among these countries who say they have a very favorable view. Likewise, majorities in Sweden, Germany, Hungary, Spain, the Netherlands and Italy hold a positive outlook toward the EU.

While more people see the EU in a positive light than not in the UK, Greece, the Czech Republic and France, these countries also have sizable portions of the public – more than four-in-ten – that voice negative opinions. In Russia, 44% have a negative view of the EU, while 37% give it a thumbs-up.

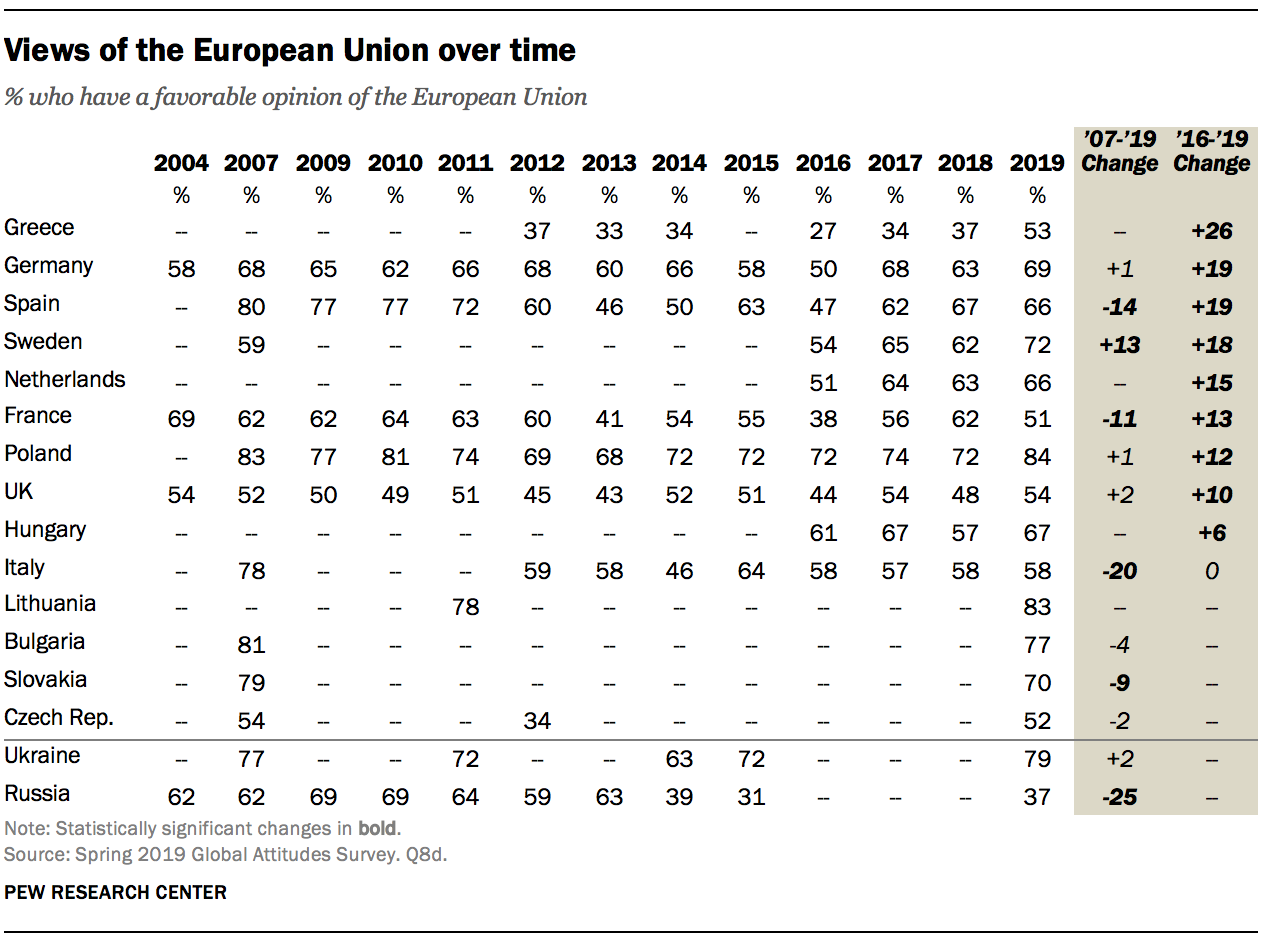

In recent years, even as euroskeptic parties have gained political momentum and British voters passed the 2016 referendum to leave the EU, short-term views of the European Union have rebounded in several countries. Greece has seen a 26 percentage point surge in favorable views of the EU from 2016 to 2019. Spain (+19 points) and France (+13) have seen large upticks in the last three years despite publics being less positive than in 2007. Among EU countries surveyed, Germany, Sweden, the Netherlands, Poland, the UK, Hungary and Italy also increasingly expressed affirmative views of the EU from 2016 to 2019.

However, long-term favorable views of the EU have not changed much in several nations polled since 2007. Germany, Poland, the UK, Ukraine, Bulgaria and the Czech Republic hold similarly positive views of the EU today compared with 12 years ago. Swedes are now 13 points more favorable toward the EU than when first asked in 2007.

But five nations have deteriorating opinions of the EU. Italy (where favorability has fallen 20 points), Spain (-14), France (-11) and Slovakia (-9) have become less pleased with the EU in the past 12 years. And non-EU member Russia shows the greatest decrease in favorable views of the European economic area, down 25 points since 2007. Still, despite some of these long-term trends, in almost every country surveyed since 2016 there has been a significant increase in favorable views of the EU.

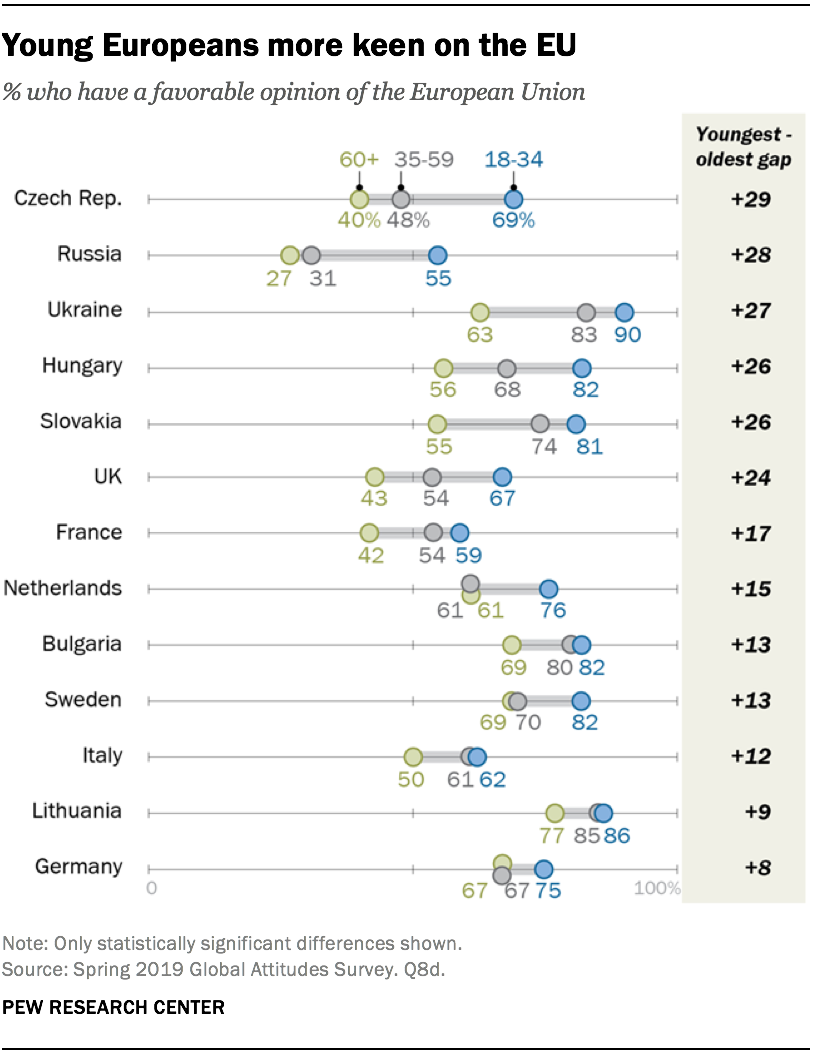

In 13 countries, younger people (ages 18 to 34) have more favorable views than older counterparts (ages 60 and older) when it comes to the EU. For example, while two-thirds of young adults in the UK have a positive view of the EU, just 43% of those 60 and older share that perspective, a 24 percentage point gap.

In 13 countries, younger people (ages 18 to 34) have more favorable views than older counterparts (ages 60 and older) when it comes to the EU. For example, while two-thirds of young adults in the UK have a positive view of the EU, just 43% of those 60 and older share that perspective, a 24 percentage point gap.

Large gaps also exist in the Czech Republic (29-point gap between youngest and oldest), Russia (+28 points), Ukraine (+27), Hungary (+26) and Slovakia (+26). However, in several of these nations, those ages 60 and older are less likely to offer any opinion about the EU. For example, 26% of older Russians give no response.

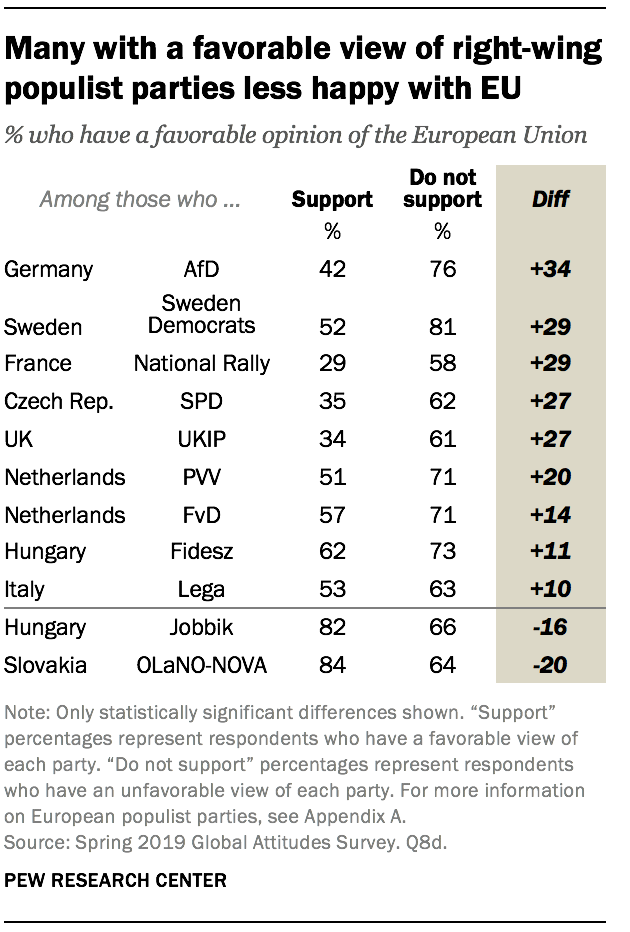

In most of the EU countries surveyed with right-wing populist parties, people with positive views of these parties tend to be much less favorable toward Brussels. The starkest difference appears in Germany, where favorable views of the EU are 34 percentage points higher among those who do not support the right-wing Alternative for Germany (AfD) party.

In most of the EU countries surveyed with right-wing populist parties, people with positive views of these parties tend to be much less favorable toward Brussels. The starkest difference appears in Germany, where favorable views of the EU are 34 percentage points higher among those who do not support the right-wing Alternative for Germany (AfD) party.

In 10 countries included in this survey, those with more education have more positive opinions of the EU; the same is true of those with higher incomes in 11 of the nations surveyed. However, in many of these countries, those with less education and lower incomes are less likely to answer the question. In six countries, people in urban areas are more likely than those outside of urban centers to have favorable views of the EU.

Those living in pre-1990 West Germany (71%) see the EU more favorably than those living in former East Germany (59%). People in Ukraine who only speak Ukrainian at home more frequently voice enthusiasm for the EU (88%), although 71% of those who speak only Russian also express a positive opinion.

Views of the economy play a large role in how people generally view the European Union. Those who think their country’s economic situation is good are more likely to have a favorable opinion of the EU in most countries surveyed. In Sweden, for example, 81% of those who think the Swedish economy is in good shape also have a positive view of the EU; just 42% of those who think the economy is functioning poorly share that sentiment.

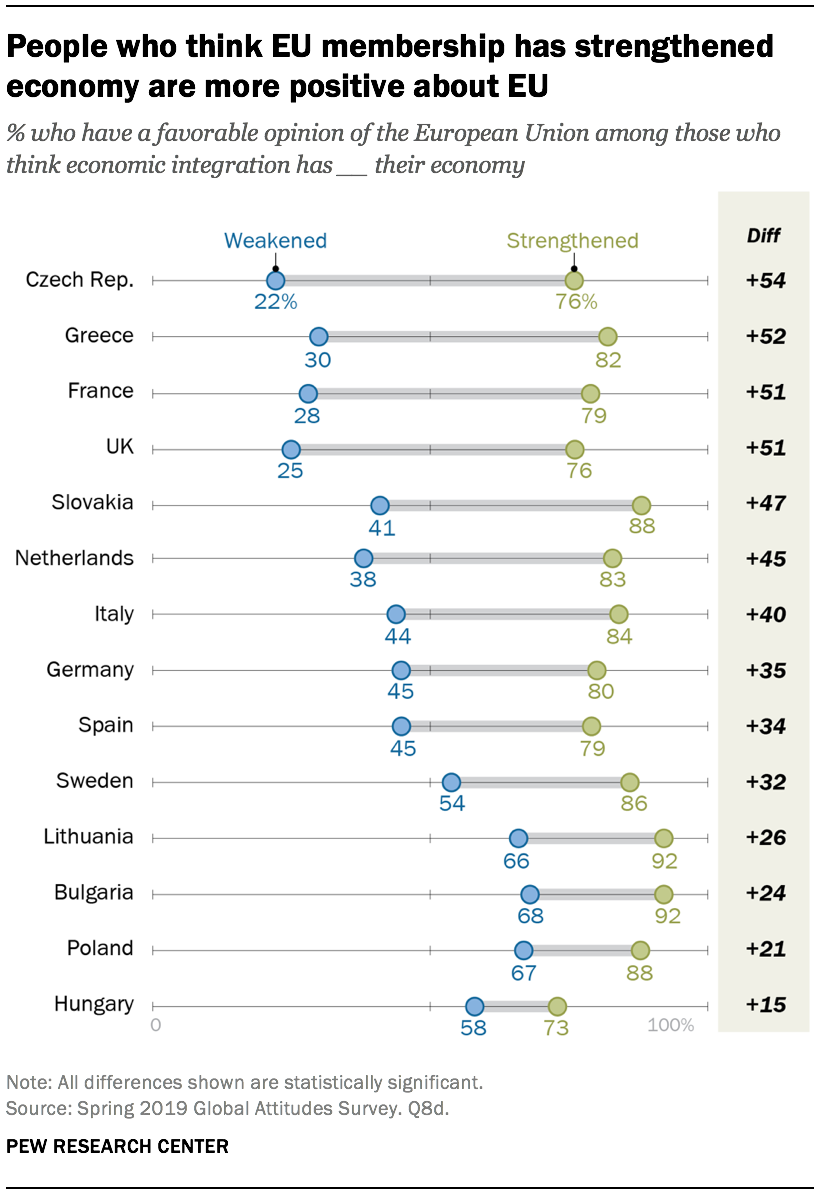

Likewise, those who think their country has benefited economically from European economic integration have more positive opinions of the Brussels-based institution. In the Czech Republic, 76% of those who think their national economy has strengthened because of economic integration have a favorable view of the EU. Among Czechs who think joining the EU has weakened their economy, just 22% are satisfied with the EU, a 54 percentage point difference. Similarly wide margins can be found in Greece (+52 points), France (+51), the UK (+51), Slovakia (+47), the Netherlands (+45) and Italy (+40).

Likewise, those who think their country has benefited economically from European economic integration have more positive opinions of the Brussels-based institution. In the Czech Republic, 76% of those who think their national economy has strengthened because of economic integration have a favorable view of the EU. Among Czechs who think joining the EU has weakened their economy, just 22% are satisfied with the EU, a 54 percentage point difference. Similarly wide margins can be found in Greece (+52 points), France (+51), the UK (+51), Slovakia (+47), the Netherlands (+45) and Italy (+40).

Many see benefits to EU membership

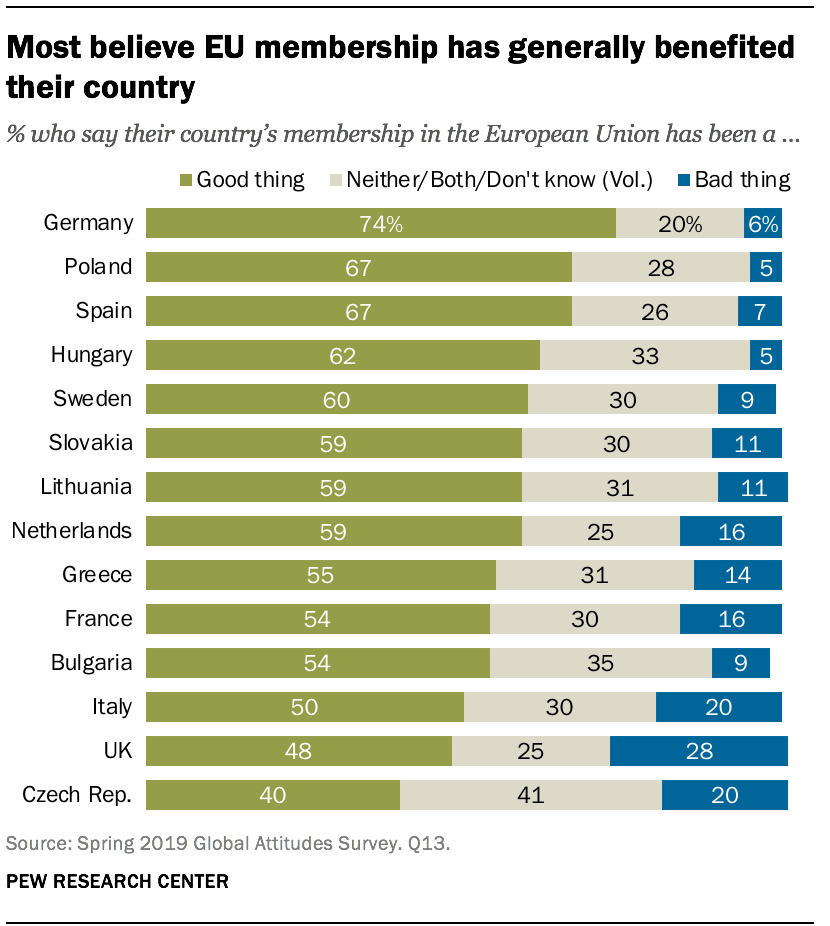

Among the 14 European Union member nations in the survey, most say joining the EU was a good thing for their country. Nearly three-quarters of Germans hold this view. Roughly half or more in all but the Czech Republic concur that EU membership has been a net positive for their country.

Among the 14 European Union member nations in the survey, most say joining the EU was a good thing for their country. Nearly three-quarters of Germans hold this view. Roughly half or more in all but the Czech Republic concur that EU membership has been a net positive for their country.

Despite generally positive reactions to their country’s EU membership, sizable groups in each country say European integration has been “neither good nor bad” or “both good and bad,” or didn’t give an answer.

In the United Kingdom, a nation embroiled in a fierce debate about Brexit, more than a quarter (28%) say their country’s membership in the EU has been a bad thing, the highest negative measure on this issue of all countries surveyed. This negative view is more prominent among Britons in rural and suburban areas (34% and 30%, respectively) than with those in UK cities (14%). British people ages 60 and older are more than three times as negative as those ages 18 to 34 about EU membership (37% bad vs. 11%). Likewise, those in the UK with less education are more likely to feel EU membership has set their country back.

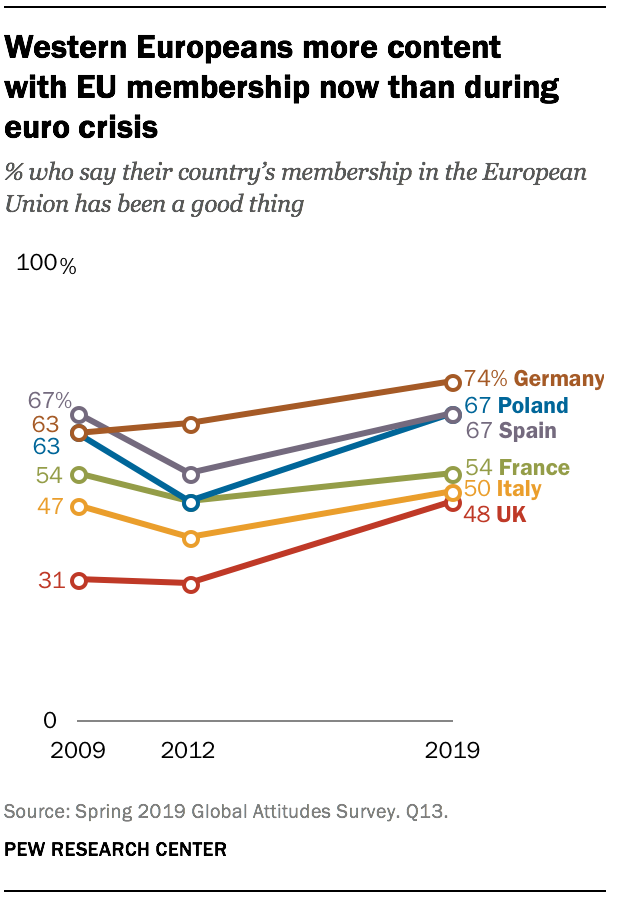

Several EU countries have become more positive about joining the EU over the past few years after some fluctuation amid economic uncertainty. Poland, Spain, Italy and France each saw a significant drop between 2009 and 2012 in those saying EU membership was good, as many nations were feeling the full effects of the European sovereign debt crisis. In these four countries, attitudes toward joining the EU have since rebounded to mirror acceptance levels prior to austerity and the euro crisis.

Several EU countries have become more positive about joining the EU over the past few years after some fluctuation amid economic uncertainty. Poland, Spain, Italy and France each saw a significant drop between 2009 and 2012 in those saying EU membership was good, as many nations were feeling the full effects of the European sovereign debt crisis. In these four countries, attitudes toward joining the EU have since rebounded to mirror acceptance levels prior to austerity and the euro crisis.

In Germany, contentment with EU membership has gained steadily since 2009, increasing by 11 percentage points over the past decade from 63% to 74%. The UK’s attitudes toward participation in the European Union started at much lower levels than in other Western European nations. Today, the UK still has the lowest level measured among Western European countries in the survey, though positive feelings about joining the EU have climbed by 17 points since 2009.

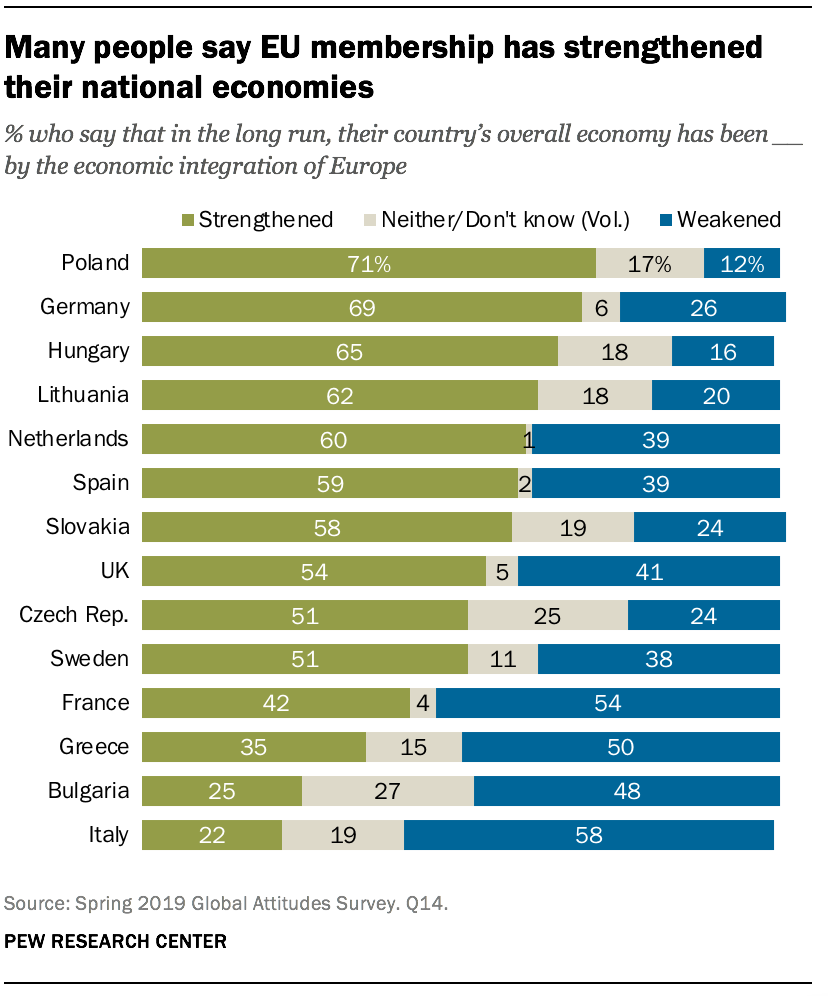

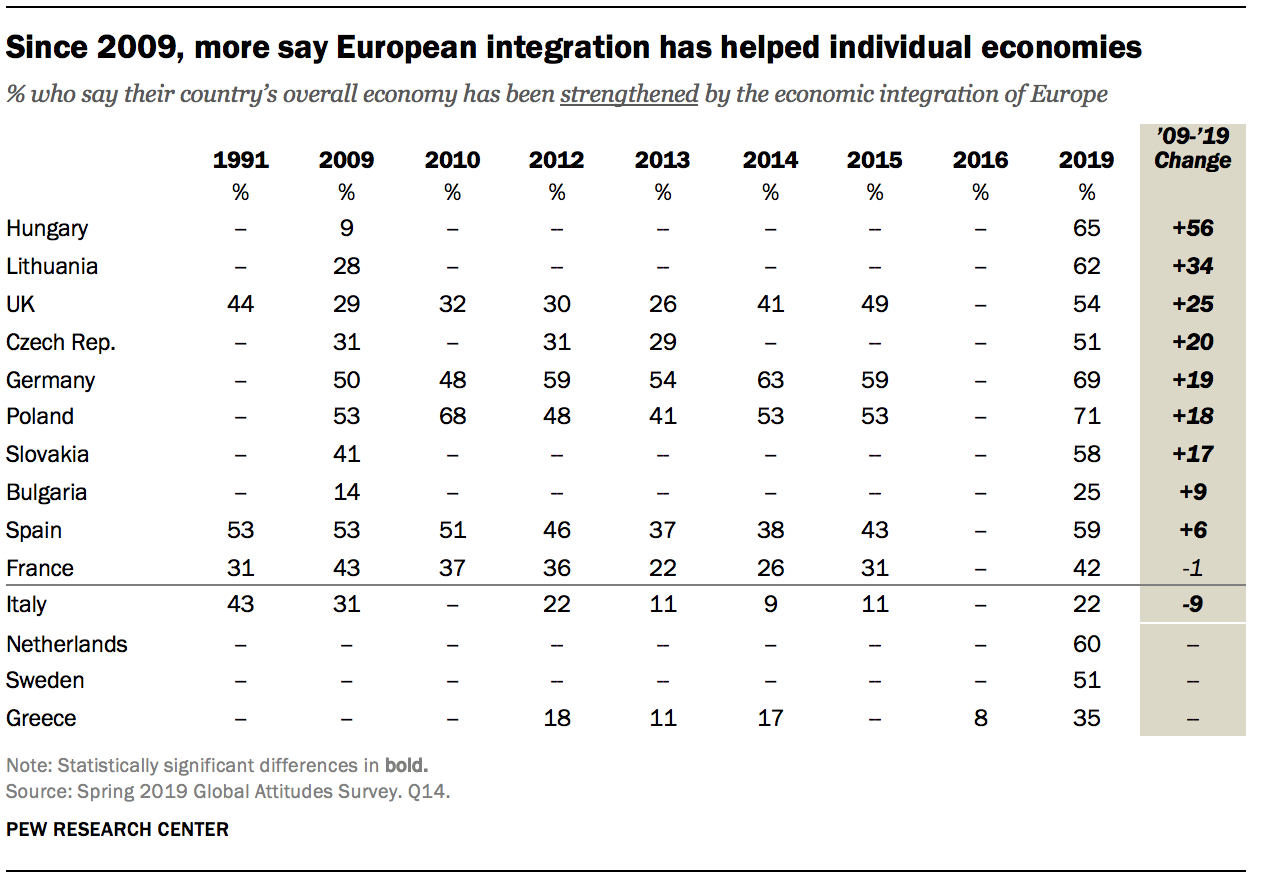

When it comes to the long-term economic effects of EU integration in their own nation, at least half of publics in 10 EU countries say their country’s overall economy has been strengthened by the economic integration of Europe; Poland, Germany, Hungary and Lithuania top this list.

When it comes to the long-term economic effects of EU integration in their own nation, at least half of publics in 10 EU countries say their country’s overall economy has been strengthened by the economic integration of Europe; Poland, Germany, Hungary and Lithuania top this list.

While most people in the Netherlands, Spain, the UK and Sweden see positive economic effects from joining the EU, sizable groups in each of these countries – roughly four-in-ten – believe their economy has suffered due to economic integration.

Most in Slovakia and the Czech Republic think their country has prospered, but smaller groups in both believe joining the EU has had a negative economic effect or has been neither good nor bad overall.

In France, Greece and Bulgaria, roughly half think European integration has weakened their national economy, and a majority in Italy agree.

In France, Greece and Bulgaria, roughly half think European integration has weakened their national economy, and a majority in Italy agree.

Those with more education are especially prone to say integration has helped their economy in most countries, as are those with incomes at or above the national median.

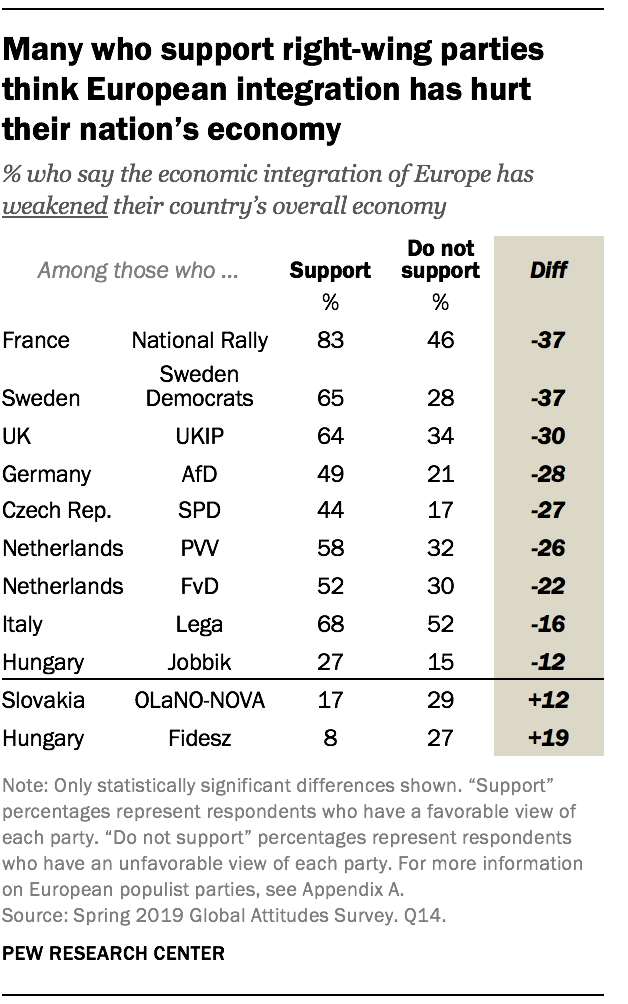

In many countries, those who support right-wing populist parties are more likely to think joining the EU has weakened their national economy. Those with favorable views of Hungary’s Fidesz party, and OLaNO-NOVA supporters in Slovakia, buck this trend and tend to think their countries have benefited economically from European integration.

Many of the nations surveyed are more positive about the economic benefits of the EU now than they were a decade ago. This is especially true in several Central and Eastern European countries.

For example, in 2009, just 9% of Hungarians said joining the EU had benefited their economy. By 2019 that number ballooned to 65%, a 56 percentage point increase. Double-digit increases can also be found in Lithuania, the UK, the Czech Republic, Germany, Poland and Slovakia.

Since 2013, some nations have seen a resurgence in positive attitudes about the EU’s effects on the national economy. French attitudes about their economy benefiting from European integration dipped down to 22% in 2013 but have since rebounded by 20 points to 42% today. Italy, likewise, dropped to 11% in 2013 but in the last six years has doubled to 22%. The six other countries surveyed in both 2013 and 2019 – Poland, the UK, Greece, the Czech Republic, Spain and Germany – have all seen significant increases over the same period.

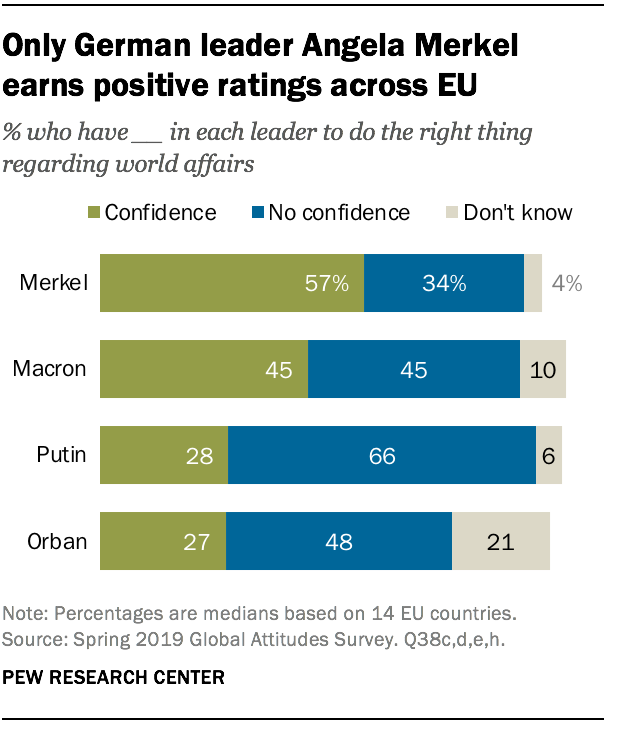

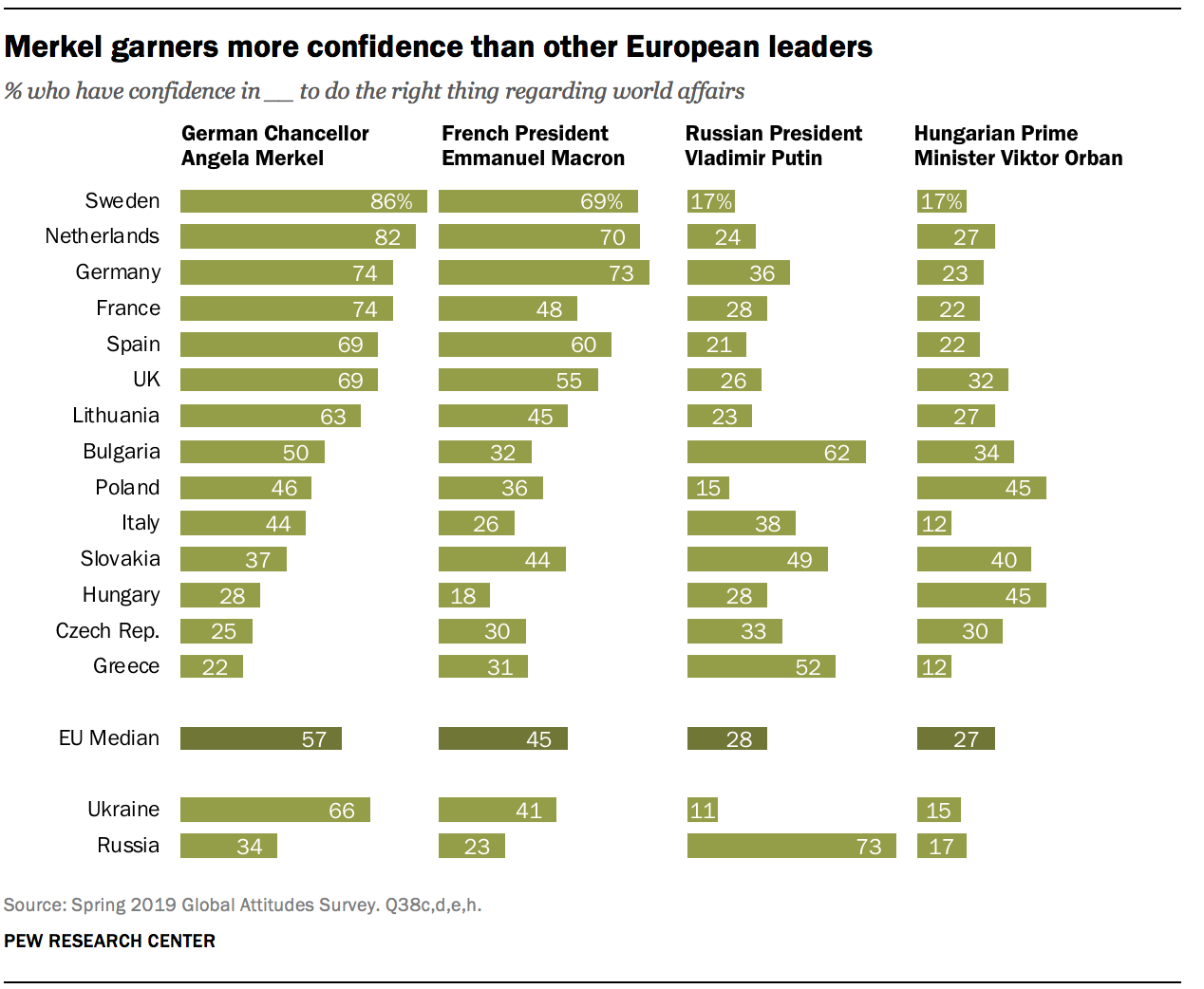

Angela Merkel more trusted in world affairs than other European leaders

German Chancellor Angela Merkel fares the best among the four leaders asked about in the survey when it comes to public confidence. A median of more than half across the 14 EU members surveyed have confidence in Merkel, who has said she will leave politics after Germany’s 2021 federal election, while a median of around a third voice no confidence. Similar to last year, Merkel’s strongest support comes from Sweden, the Netherlands and France, which rate her higher than those in her native Germany. Still, nearly three-quarters of Germans have confidence in Merkel to do the right thing when it comes to world affairs, including 75% of those who live in former West Germany and 68% in former East Germany, where Merkel grew up. Majorities in Spain, the UK, Ukraine and Lithuania also voice confidence in the German leader.

German Chancellor Angela Merkel fares the best among the four leaders asked about in the survey when it comes to public confidence. A median of more than half across the 14 EU members surveyed have confidence in Merkel, who has said she will leave politics after Germany’s 2021 federal election, while a median of around a third voice no confidence. Similar to last year, Merkel’s strongest support comes from Sweden, the Netherlands and France, which rate her higher than those in her native Germany. Still, nearly three-quarters of Germans have confidence in Merkel to do the right thing when it comes to world affairs, including 75% of those who live in former West Germany and 68% in former East Germany, where Merkel grew up. Majorities in Spain, the UK, Ukraine and Lithuania also voice confidence in the German leader.

Merkel fares worse in other countries: Fewer than four-in-ten give her positive ratings in Slovakia, Hungary, the Czech Republic and Greece. And only about one-in-three Russians have confidence while roughly half do not.

French President Emmanuel Macron receives mixed reviews from the surveyed nations: A median of 45% across the 14 EU member countries have confidence in him, while 45% say they do not. Majorities in Germany, the Netherlands, Sweden, Spain and the UK all rate the French leader favorably. In his home country of France, 48% voice confidence in Macron.

Among EU nations surveyed, Macron’s largest detractors outside of France can be found in Italy and Greece (65% and 58% lack confidence in him, respectively). The French president also does not fare well in some Central and Eastern European countries, such as Hungary, Poland, Bulgaria and the Czech Republic, where about half say they have no confidence in Macron, but roughly one-in-five respondents or more in these nations do not give any opinion of the French leader.

A median of 28% in the 14 EU countries surveyed have confidence in Russian President Vladimir Putin. Putin receives the highest marks in Russia, where nearly three-quarters have confidence in their leader. About half or more Bulgarians, Greeks and Slovaks also view the Russian leader positively. One-quarter or fewer have confidence in Putin in Lithuania, Sweden, Spain, Poland and the Netherlands. And in neighboring Ukraine, only a scant 11% have confidence in Putin.

Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban garners the lowest median confidence across the 14 EU nations when it comes to world affairs, with just 27%. Orban fares best in his home nation of Hungary, Poland and neighboring Slovakia. Hungarians ages 60 and older have more confidence in Orban’s ability to handle world affairs. The Hungarian leader comes off poorly in Sweden, Russia, Ukraine, Italy and Greece, with fewer than 20% voicing confidence in each nation. However, a median of 21% across the 14 countries surveyed offer no opinion about Orban. Six-in-ten or more in Ukraine (67%) and Russia (60%) also give no opinion of the Hungarian leader.

Support for a right-wing populist party and views of European leaders are related. In 10 countries, those with favorable views of a right-wing populist party are also more likely to have confidence in Putin when it comes to world affairs; the same pattern appears for Orban. At the same time, those who dislike a right-wing group tend to hold positive views of Angela Merkel (seven countries) and Emmanuel Macron (eight countries).

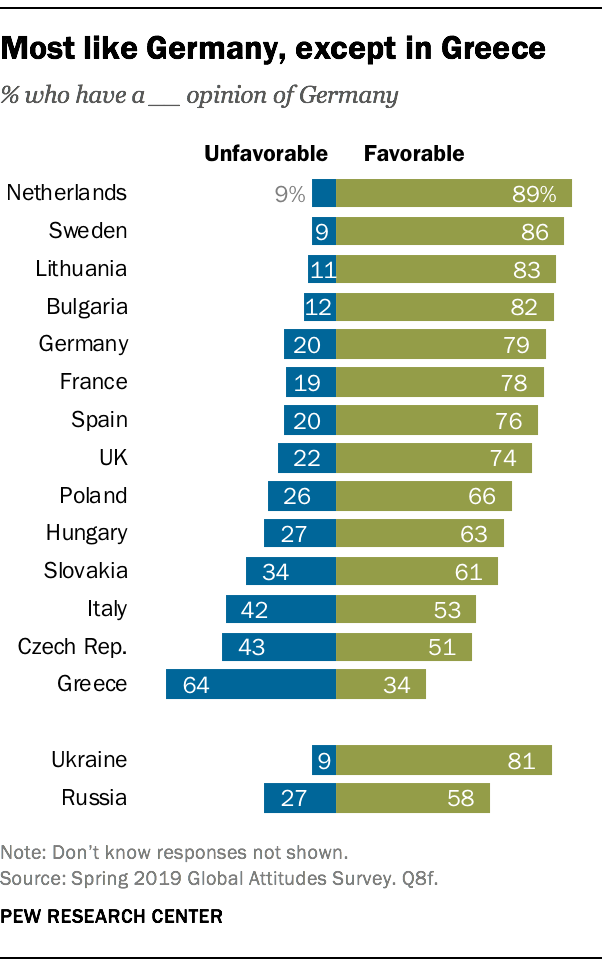

Views of Germany positive except in Greece

Germany, the largest economy in the EU, enjoys favorable reviews from most other European publics surveyed. Majorities in 11 EU nations have a positive outlook toward Germany, as do Ukrainians and Russians. While roughly half of those in the Czech Republic and Italy share favorable views of Germany, about four-in-ten voice negative opinions.

Germany, the largest economy in the EU, enjoys favorable reviews from most other European publics surveyed. Majorities in 11 EU nations have a positive outlook toward Germany, as do Ukrainians and Russians. While roughly half of those in the Czech Republic and Italy share favorable views of Germany, about four-in-ten voice negative opinions.

The main dissenters when it comes to views of Germany are the Greeks: Roughly two-thirds (64%) have a negative opinion of Germany, while just 34% hold positive opinions. This frustration is not new. As far back as 2012, Greece most frequently named Germany as the least trustworthy, most arrogant and least compassionate country in the EU. However, overall favorable views of Germany among the Greeks are up 13 percentage points from 2012, when just 21% gave Germany a favorable rating amid austerity and the Greek debt crisis.

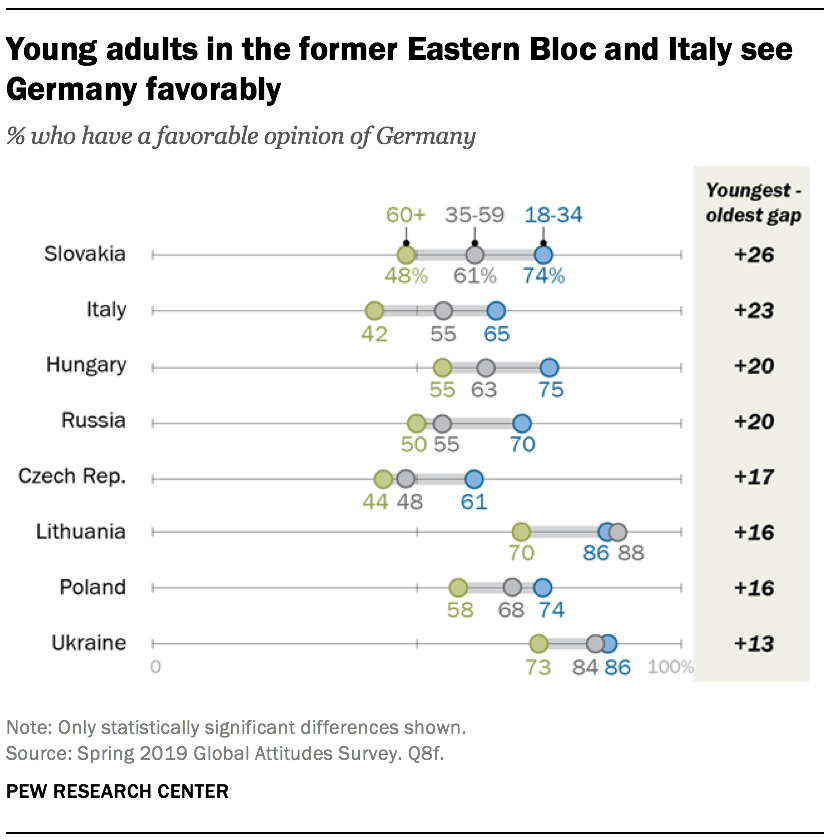

Views of Germany in several former Eastern Bloc nations diverge across age groups. In seven of eight of these nations, younger people ages 18 to 34 are more positive than those ages 60 and older when it comes to Germany. One of the largest gaps can be found in Slovakia, where 74% of younger Slovaks see Germany favorably compared with just 48% of their older counterparts. Older Lithuanians and Russians are also more likely to not provide a response.

Views of Germany in several former Eastern Bloc nations diverge across age groups. In seven of eight of these nations, younger people ages 18 to 34 are more positive than those ages 60 and older when it comes to Germany. One of the largest gaps can be found in Slovakia, where 74% of younger Slovaks see Germany favorably compared with just 48% of their older counterparts. Older Lithuanians and Russians are also more likely to not provide a response.

In Western Europe, an age divide exists only in Italy: 65% of the younger generation has positive opinions about Germany while just 42% of older Italians agree.

Education also plays a role in perceptions of Germany: In 13 nations, those with more education are more favorable toward Germany than those with less education. In Hungary, those with less education are also less likely to provide a response.

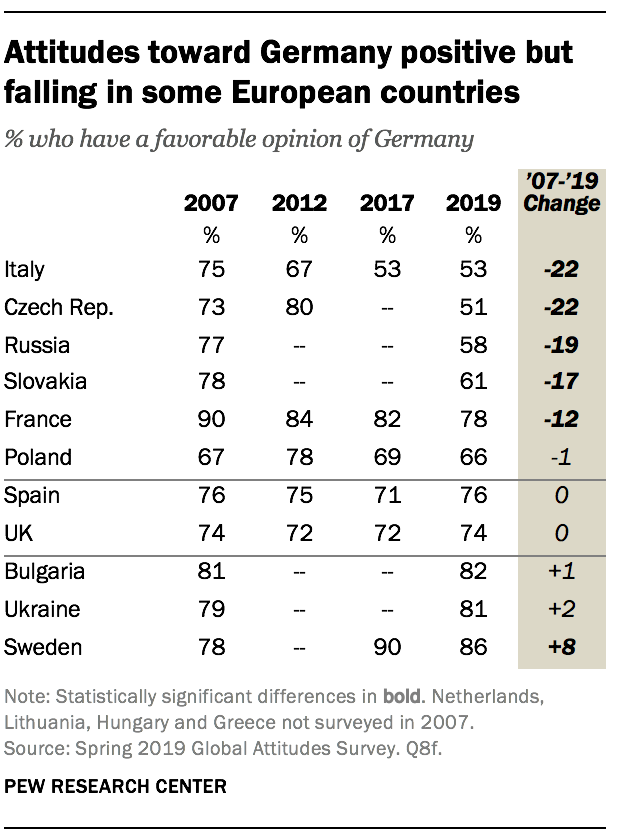

In several countries, attitudes toward Germany have soured a bit over the past decade or so. There have been double-digit declines in positive views since 2007 in Italy, the Czech Republic, Russia, Slovakia and France.

In several countries, attitudes toward Germany have soured a bit over the past decade or so. There have been double-digit declines in positive views since 2007 in Italy, the Czech Republic, Russia, Slovakia and France.

Assessments of Germany have remained largely unchanged – and overwhelmingly positive – in Poland, Spain, the UK and Ukraine over the last 12 years. The only country that has become more positive toward Germany over the same time frame is Sweden, where favorable views have increased by 8 percentage points.

In six European countries, those with favorable views of a right-wing populist party have less favorable views of Germany. For instance, in the Czech Republic, only 45% of those who sympathize with the Freedom and Direct Democracy (SPD) party offer up a favorable view of Germany, compared with 55% of those who do not support SPD.

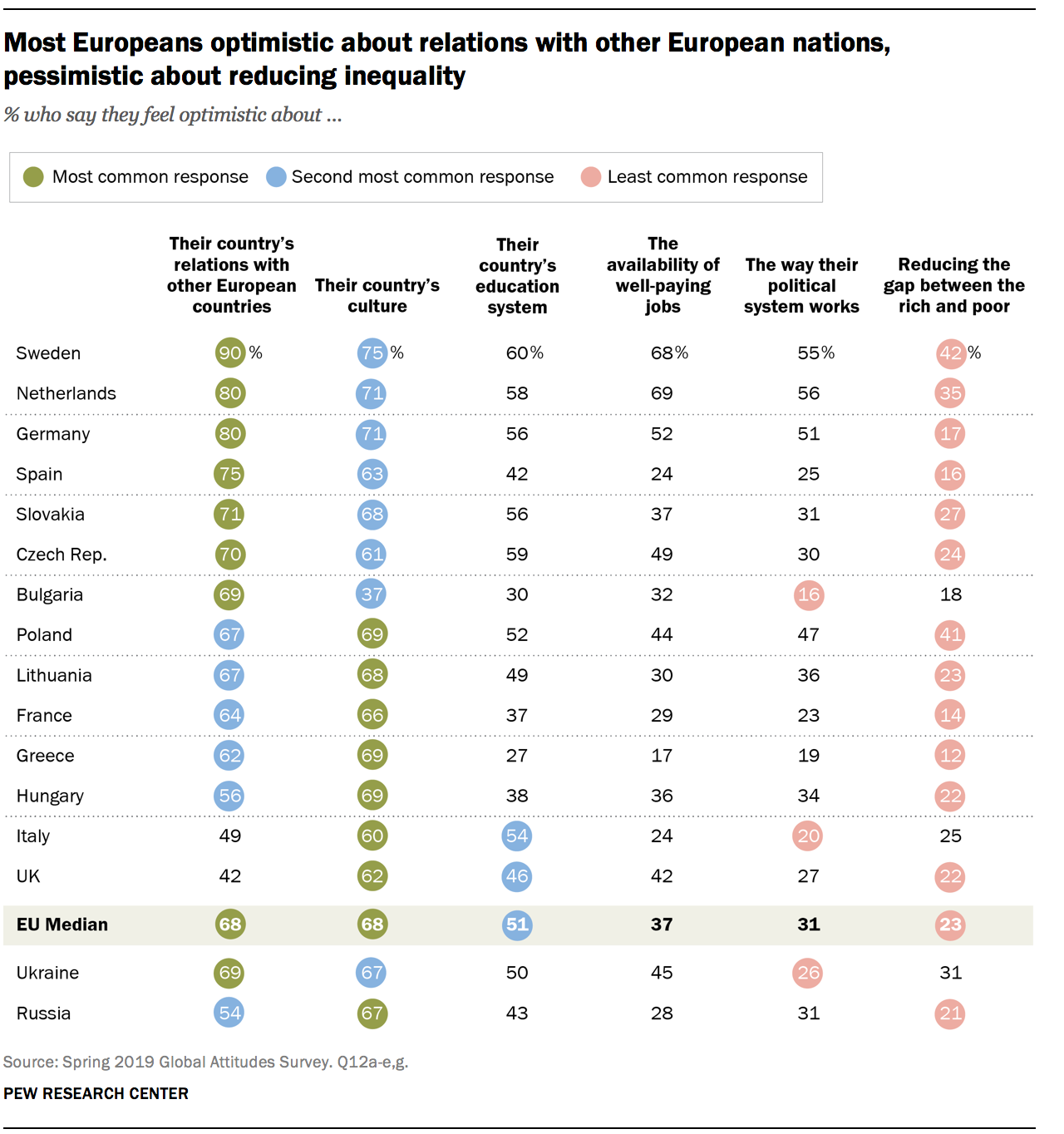

Europeans most optimistic about their culture, relations with other European nations

A median of 68% across 14 EU member countries say that, when thinking about the future of their country, they are optimistic when it comes to their country’s relations with other European nations as well as their national culture. In fact, their own country’s culture was the first- or second-most named area for optimism in every nation surveyed; all but Italy and the UK also chose relations with other countries in Europe as a source of optimism.

For 54% of Italians and 46% of Britons, their nation’s education system was the second most commonly cited reason for feeling optimistic about the future. While not a top choice elsewhere, at least half of publics in seven other countries also felt hopeful about their education system.

When it comes to the availability of well-paying jobs, a median of just 37% feel a sense of optimism. And while the EU’s overall unemployment rate has fallen to its lowest point in almost a decade, the job situation is not equally hopeful in each individual EU member country. In Greece, for example, where only 17% voice optimism about their country’s job prospects, the unemployment rate was 19.3% in 2018, the highest such rate in the EU by far. Fellow employment pessimists in Spain and Italy have relatively high unemployment rates of 15.4% and 10.8%, respectively. Across the 14 EU member nations in the survey, nations with higher unemployment rates tend to voice more pessimism about their prospects for well-paying jobs.

People also expressed a lack of confidence when it comes to politics: A median of 31% across the 14 EU countries said they were optimistic about the way their country’s political system functions. In most countries, supporters of the current governing party or coalition of their government are more optimistic about their political system than nonsupporters.

Only 23% across the 14 EU countries are optimistic about reducing inequality, and in most countries surveyed, people are the least optimistic about this issue.